Writing is all about choices - a story is made or broken by what the author chooses, how they choose to convey it, and even the ways holes they leave behind. Whether conscious or not, the very act of writing involves making millions of tiny choices, and they all matter.

Which is why it's often super interesting to step back and pin down some of those choices, and take a minute to understand why we made them, and what other options might be. So read through the articles below (indeed, any of those in our archives), and take a moment to think about those choices, and how they might be questioned to make something bigger.

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Point of View, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 63

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Rhetorical Devices, Best of AYAP, Point of View, POV, Theme, Add a tag

Blog: The Bookshelf Muse (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Uncategorized, Point of View, Characters, Guest Post, Add a tag

Becca and I see certain questions pop up in our email boxes over and over, and one that always comes up during NaNoWriMo season is the question of how many POVs a novel should have.

Like so many questions, this isn’t a cut-and-dry answer; so much depends on the type of story being told, what the author needs to achieve through multiple POVs, and to a lesser degree, the experience of the writer themselves. So I’m happy author Marcy Kennedy is here with some excellent metrics to consider when planning a novel and choosing how many POV characters to include.

Like so many questions, this isn’t a cut-and-dry answer; so much depends on the type of story being told, what the author needs to achieve through multiple POVs, and to a lesser degree, the experience of the writer themselves. So I’m happy author Marcy Kennedy is here with some excellent metrics to consider when planning a novel and choosing how many POV characters to include.

One of the most common challenges for us as writers is deciding how many point-of-view characters we should use, and yet a lot of the advice we hear can be too generic. Use the right number for your genre. Don’t use more than three.

One of the most common challenges for us as writers is deciding how many point-of-view characters we should use, and yet a lot of the advice we hear can be too generic. Use the right number for your genre. Don’t use more than three.

While those tips are good general advice, they’re often not specific enough to actually answer our question. Our story might seem to need more than the standard advice would recommend. Or there might not even be a “standard” for our genre. How do we decide how many point-of-view characters to include?

One technique we can use for figuring out what’s best for our individual story is to write down all the potential point-of-view characters we might want to use, and then ask ourselves the following questions.

Who is the protagonist?

Our protagonist is the person whose goal drives the story. Most of the time, we need our protagonist to also be a point-of-view character (and to receive the majority of our scenes). Identify them first, and then you don’t have to consider them in the rest of the questions.

Would it improve the story to include scenes from the antagonist’s viewpoint?

In some stories, we don’t want to delve into the mind of our antagonist, either because the antagonist is an especially twisted villain or because revealing the identity or plans of the antagonist would ruin the tension. In other stories, knowing the antagonist and his or her plans increases the tension as readers worry about whether our heroes will spot the trap in time.

What’s the scope of our story?

An epic fantasy spanning five planets where the fate of the galaxy is at stake might require more point-of-view characters than the coming-of-age story of a young woman in feudal Japan. Generally speaking, the smaller the scope, the fewer point-of-view characters we need. The larger the scope, the more we can reasonably use, but that doesn’t mean we must or should—which is where the other questions come in.

Does every potential point-of-view character influence the plot in a significant way?

This is a good question for checking that each potential point-of-view character is essential. If a character could be cut without having to change the plot in any significant way, or if another character could easily step in and take their place, they probably aren’t a good choice for a point-of-view character because they’re expendable.

Does including this point-of-view character’s perspective enhance the theme?

Theme is always a tricky area for writers. We don’t want readers to feel like we’re beating them over the head with our message. Theme should develop through our main character’s growth arc and the challenging decisions they face, but another way to enhance our theme is to have characters approach it from varying angles and to take different sides on the issue. Those other characters don’t necessarily need to be point-of-view characters, though. So what we want to look at is whether we need to be inside a character to truly understand their opinion and stance on the issue.

Say we’re writing a mystery and we have a detective and her partner. The detective is our protagonist. She’s the one driving our story. So do we also need scenes from the viewpoint of her partner? Maybe, maybe not.

If he’s only there to be her sounding board, then we probably never need to go into his head. But, instead, if they’re investigating a crime involving a local church and her partner is a devout Christian, then his perspective on the events and on the people involved would add new layers we couldn’t develop if all we had was the viewpoint of our atheist detective.

Which characters play a key role at the climax of the novel?

Our whole story builds up to the climax or the “final battle” where our characters fight the antagonist. The characters who are instrumental during this climax are the ones who are most important in the story. These are also good characters to consider for roles as point-of-view characters. If a character isn’t involved in the climax of the story, that’s a clue they might not be important enough to be a point-of-view character.

How many scenes might I give this character in their point of view?

If we’re only considering giving them one or two scenes, it usually means we want to make this person a point-of-view character to shoehorn in information or to show a part of the story that doesn’t need to be shown. Those aren’t good reasons to make someone a point-of-view character.

Each point-of-view character we include needs to have goals, motivations, and stakes within the story and to give a valuable, necessary perspective on the situation.

POINT OF VIEW IN FICTION:

POINT OF VIEW IN FICTION:

Point of view is the foundation upon which all other elements of the writing craft stand—or fall.

It’s the opinions and judgments that color everything the reader believes about the world and the story. It’s the voice of the character that becomes as familiar to the reader as their own. It’s what makes the story real, believable, and honest.

Yet, despite its importance, point-of-view errors are the most common problem for fiction writers.

In Point of View in Fiction: A Busy Writer’s Guide, you’ll learn

- the strengths and weaknesses of the four different points of view you can choose for your story (first person, second person, limited third person, and omniscient),

- how to select the right point of view for your story,

- how to maintain a consistent point of view throughout your story,

- practical techniques for identifying and fixing head-hopping and other point-of-view errors,

- the criteria to consider when choosing the viewpoint character for each individual scene or chapter,

- and much more!

Amazon | iTunes | Barnes & Noble | Kobo

Marcy Kennedy is the author of the bestselling Busy Writer’s Guides series, which focuses on giving authors deep teaching while still respecting their time. You can find her blogging about writing and about the place where real life meets science fiction, fantasy, and myth on her website.

Have a POV question for Marcy? This is an excellent opportunity to pick her brain on all things Point-of-view!

The post How to Decide How Many POV Characters Our Book Needs appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS™.

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: science fiction, Point of View, series, POV, Craft of Writing, character names, Ask a Pub Pro, Stefanie Gaither, Add a tag

We are thrilled to welcome author Stefanie Gaither to the blog this month as our columnist for Ask a Pub Pro! Stefanie is the author of the very popular and thrilling Falls the Shadow, with the sequel coming in 2016. She's here to answer your reader questions on unusual names for fantasy, how many books can an author squeeze into a series, the balance of fiction and fact for science fiction, and how many POV characters can make up an ensemble.

If you have a question you'd like to have answered by an upcoming publishing professional, send it to AYAPLit AT gmail.com and put Ask a Pub Pro Question in the subject line.

Also, please do not forget next week's Happy Potter Birthday celebration! If you were inspired to write, or if your writing was any way influenced by JK Rowling, we'd love to hear from you! Please send a paragraph (or two) telling us how Harry Potter influenced your writing and you may be included in next week's celebration.

Email posts to AYAPLit AT gmail.com, and please put Happy Potter Day in the subject line. We'll let you know before July 31 if yours is one of the submissions chosen.

Author Stefanie Gaither on Character Names, Science Fiction Research, and POV

1) Writer Question: I'm worried about the names I'm creating for my WIP. My story is a fantasy, and the names I've envisioned sometimes have hyphenated endings to add a suffix meaning onto the name. But it seems that I've heard hyphens in names are frowned upon. I'm keeping the names very simple, even with the hyphens, so that it will not be confusing to the reader. Do you think that will work? Or would the use of hyphens be too off-putting? Would an apostrophe be better?

I actually just finished up a fantasy WIP of my own, so I understand the name struggle :) I don’t think that hyphens in names are immediately off-putting—so long as it fits the story and/or character. Other readers may feel differently, of course. If you’re really concerned about it, maybe there’s a way to compromise? Have their formal name hyphenated, but perhaps they go by a nickname that flows more easily for the reader?

Either way, one thing I like to do when figuring out names is to ask people unfamiliar with my story/character what comes to mind when I mention a person named “XYZ” or whatever; in your case, maybe write the name and then ask friends and fellow writers what immediately jumps into their minds when they see it—and if it’s in line with what you’re going for with this particular character, then you’re golden. Poll as many people as you can. Of course, not everyone will have the same answer, but it will give you a general idea of what the name you came up with is “showing” potential readers about this character—and whether or not they’re stumbling over things like hyphens.

Read more »

Blog: Design of the Picture Book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: scale, composition, movement, perspective, layout, Phaidon, size, Uncategorized, point of view, voice, Add a tag

by Stella Gurney and Natsko Seki (Phaidon, 2013)

Do kids’ books have room for one more smart pigeon? You’ll be glad you let this one in, because Speck Lee Tailfeather is another flier with a healthy confidence and a chatty nature.

Speck’s mission is world travel, focusing on buildings from a bird’s point of view. He sees things differently.

His words are a travel journal of sorts to his pigeon friends. To his love, Elsie. And to us.

There’s a lot to look at, from speech bubbles to side bars to fascinating tidbits. The layout and voice are both unusual in the very best way. And if you just shake off what you expect from picture books and settle in, your flight from city to sky and back will be worth it.

Your tour guide, after all, is an expert in the unusual.

This one is for treasure hunters, trivia fanatics, architecture buffs, or anyone hungry for some off-the-wall-pigeon-fare. You never know.

Pair it with A Lion in Paris. Speck travels farther than France, but matching up the Parisian buildings (not to mention the books’ head-to-head size battle and their animal points of view) would be a fun thing for storytime.

Add a CommentBlog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Point of View, Character Development, Craft of Writing, Ask a Pub Pro, Helene Dunbar, Add a tag

Welcome to our monthly Ask a Pub Pro feature where a publishing professional answers readers and writers' questions regarding the stories they love or their work in progress. This month, Helene Dunbar, author of These Gentle Wounds and the soon-to-be-released What Remains joins us to answer questions on humor in dark scenes, unsympathetic characters, present tense, and multiple POVs.

We'd love to have you send in your questions for next month's column. Please send questions to AYAPLit AT gmail.com and put "Ask a Pub Pro Question" in the subject line. If your question is chosen, you'll get to include a link to your social media and a one to two sentence (think Tweet size) blurb of your WIP.

Come on! Get those questions in!

Author Helene Dunbar Answers Questions on Ask A Pub Pro

1) My question is regarding humor in dark moment scenes. I have a character who's a smart mouth. If he says something funny (dry) in a very dark scene, will that lesson the tension? (asked by Sylvia in NJ)

|

| source |

This is also where crit partners or beta readers are great resources because they’ll be the first to tell you if a scene is being marred by a character’s response. But I’ve often found that a tense scene can be made tenser by someone saying the unexpected thing that maybe cuts deeper than the expected comment would.

2) I tend to write protagonists that are not perfect....I mean really not perfect, as in more anti-hero than hero...and have had a lot of complaints about sympathy. But to me, the greater character arc comes from someone who has a longer way to go. Is this kind of character just not marketable? Or how do I make them so? (asked by Anonymous)

I agree with you that sometimes the most interesting character arcs are those in which the character has a great distance to go. However…just because a character starts out immensely flawed, doesn’t mean that the reader can’t sympathize with them. For instance, your character might be a total self-serving narcissist who irritates everyone he/she meets except…they have a soft spot for their little sister and take her to the park at 1pm every Saturday regardless of what else they’re asked to do. I think that showing the softer side of a hard character can go very far in rounding out the character and might give you some extra ammunition in ramping up their arc.

That IS a very common criticism though, so make sure that your character is human enough or believable enough or fleshed out enough so that regardless how flawed they are, there is something to make the reader root for him/her.

3) My WIP is currently in first person present tense. I know there may be marketing challenges to using this tense, but am wondering if there are any guidelines craft-wise for writing in present tense. (asked by Anonymous)

|

| source |

As for guidelines, there are some awesome posts on Mary Kohl’s blog: kidlit.com. But I think the most important craft element to writing in first is to remember that you’re in the character’s head, you aren’t listening to a story. So, for instance, make sure that you go back and look for characters saying things that are unnecessary.

Example 1: I saw the kite floating high in the sky and it looked to me as if it might sail on forever.

Example 2: The kite floats high in the sky, looking like it might sail on forever.

You simply don’t need to say, “I saw” and “it looked to me as if” because you’re in the character’s head and most people, when they’re thinking to themselves simply register what they’re seeing or doing.

When I write in first person present I always do a revision draft to look for this. It will help keep your word-count down, help avoid starting every sentence with “I”, and will allow the reader to more closely relate to your character.

4) How many POVs is too many POVs? If I want to work with an ensemble cast, can I do 3 POVs switching off between them each scene, one per scene? (asked by Aaron in WA)

Ha! If you only knew how relevant this question was for me at the moment. Anyhow….how many is too much? It’s too much when you can’t keep the voices of the characters clear enough for the reader to identify without chapter headings that use the character’s name. (I’m making the assumption that you mean “chapters” and not “scenes” because changing characters a couple of times within each chapter is going to be challenging to say the least.)

Here’s my number one rule of writing craft: There are no rules so long as you can do it well. Seriously. Rules are for “what usually works.” But if you can pull of something brilliant that doesn’t follow anyone else’s rules, than by all means, do so.

Two authors that pull of multiple POVs extremely well are Melissa Marr (I believe that the final book of the Wicked Lovely Series had 15 POVs or something absurd and it was handled perfectly) and Maggie Steifvater (The Raven Boys series to me, is a masterclass in writing 3rd person, multiple POVs and still feeling like you’re in the head and heart of every single character. I honestly have no idea how she does it, but I’m determined to find out.)

About the Book:

In less than a second...

... two of the things Cal Ryan cares most about--a promising baseball career and Lizzie, one of his best friends--are gone forever.

In the hours that follow...

...Cal's damaged heart is replaced. But his life will never be the same.

Everyone expects him to pick up the pieces and move on.

But Lizzie is gone, and all that remains for Cal is an overwhelming sense that her death was his fault. And a voice in his head that just...won't...stop.

Cal thought he and his friends could overcome any obstacle. But grief might be the one exception.

And that might take a lifetime to accept...

Amazon | Indiebound | Goodreads

About the Author:

Helene Dunbar is the author of THESE GENTLE WOUNDS (Flux, 2014) and WHAT REMAINS (Flux, 2015). Over the years, she's worked as a drama critic, journalist, and marketing manager, and has written on topics as diverse as Irish music, court cases, theater, and Native American Indian tribes. She lives in Nashville with her husband and daughter, and exists on a steady diet of readers' tears.

Website | Twitter | Goodreads

-- posted by Susan Sipal, @HP4Writers

Blog: A Year of Reading (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: compare and contrast, picture book, point of view, Add a tag

A Tale of Two Beasts

by Fiona Roberton

Kane Miller, 2015

review copy provided by the publisher

I have a whole collection of books that have two stories that dovetail in the middle. This one is similar, but instead of dovetailing, it has two parts, each told from a different point of view.

In the first part, a little girl discovers a strange beast stuck in a tree in the forest. She rescues it, takes it home, feeds it, dresses it, walks it, and shares it with her friends. The minute she opens the window, the beast runs away. Later that night, when the little girl is lying awake in her bed trying to figure out where she went wrong, the beast comes back.

In part two, a small furry forest animal (maybe a squirrel?) tells the story of being "ambushed by a terrible beast!" This beast ties him up and carries him away to her lair where he is subjected to any number of indignities. Finally, when she opens the window, he is able to escape. Later that night, when he is hanging upside down from a tree in the forest, he realizes that there might be a reason to go back.

Same story, two different points of view. Is there one beast in this story, or are there two? Depends how you look at it!

A fun book for children of any age who are working to understand point of view.

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Lisa Colozza Cocca, Ask a Pub Pro, Point of View, Trends, POV, Add a tag

Today is our first Ask a Pub Pro response post! This is the first of a monthly feature where writers can ask specific craft questions regarding their work in progress and get a response from a publishing professional.

Joining us today to answer your questions is Lisa Colozza Cocca, author of Providence, a YA novel from Merit Press/F&W Media plus almost a dozen nonfiction titles. We appreciate Lisa guiding us through our first post as she takes your questions and answers them with her warmth and insight. Plus, she's giving away a copy of her book! Check the Rafflecopter at the end!

Remember to get your questions in for next month's Ask a Pub Pro column. Just send an email to me, Susan Sipal, at AYAPLit AT gmail and put "Ask a Pub Pro Question" in your subject line. And thank you, Lisa!

Ask a Pub Pro - Lisa Colozza Cocca Responds to Questions on POV and Trends

Question: POV in YA:

I've written my first three YA\MG novels in first person past and first person present tense. While I enjoy first person, I'd still like to switch to third person with multiple POVs. Does the average YA reader insist on first person? I'm sure there are third person YAs out there, but I can't recall the last time I've read one.

Thanks!

-- Ron Estrada, author of: Now I Knew You, contemporary YA with a touch of the supernatural -- What if you visited heaven and everything you thought important turned out to be meaningless? And that you've ignored all that truly is important.

Hi Ron,

Since you’ve been thinking about exploring new-to-you POVs, you’ve probably Googled the topic and found thousands of posts on the subject. Most advocate first person for YA, because of the intimacy it builds between the reader and the character telling the story. This is a good reason to use first person, but by no means are you limited to that point of view. I think the only thing YA readers insist upon is a story they can connect with.

One advantage of third person over first person is it gives readers a broader view. This can be especially important if you’re writing fantasy and building a new world. Are there things in your story you want your readers to see or know that your main character does not notice or know? Third person narration can fill in the gaps. Have you read Ann Brashere’s Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants? It’s been quite a while since I read it, but if I remember correctly it is written in third person with multiple viewpoints. There are plenty of teens who read the Harry Potter series too. That series is another example of third person point of view.

I do think though you have to start with the story. Let the story you want to tell determine the point of view. Don’t pick a point of view and then shape a story around it. Story always comes first.

Of course, knowing how that story wants to be told isn’t always easy, is it? Try writing the first 1-3 chapters in first person. Then go back and write the same chapters in first person alternating viewpoints. Make a third run through the same story points, but from third person alternating viewpoints. Finally, try it with third person omniscient. Read through all versions several times. With the omniscient version, note how many times you ask your reader to flip from one character’s head to another. Is there time for the reader to develop a sense of loyalty to any one character?

If you’re just looking to explore POV, you could do the above exercise with an existing YA written by someone else. Rewrite the first chapters from different points of view and compare them.

Good luck with your next novel and with discovering how your story wants to be told.

-- Lisa

|

Question: Trends & Originality:

As I've been writing my story, so many of the plot points that I thought were fairly original have come to the public consciousness recently in other ways: controlling ones dreams (Inception), ley lines (The Librarians), Scotland (Outlander, and other books/shows set there). My question has to do with "riding the wave of popularity." I'm worried that by the time my WIP is polished and sent to an agent, the answer I'll get back is "it's too derivative, we need something fresher." What do you suggest?

-- Suzanne Lucero, her WIP: In Dreams Unbidden, a YA novel. When an American teen visits Scotland for the first time she starts catching glimpses of the future in her dreams, some harmless, some deadly.

Hi Suzanne,

I suggest you finish writing and polishing your story. What you’re experiencing is pretty common – that feeling of ‘that’s my idea!’ while reading another book or watching a show. I understand your concerns. If an agent or editor has already received fifty queries for books on Celtic trails will she even consider query 51? Maybe not, but maybe she will if it is a really well-written query. Maybe she will because even though you imagine she has received countless queries on the topic, in reality she hasn’t. There are so many ‘maybes.’

The point I’m trying to make is you can’t predict what an agent or editor will be looking for at some point in the future. I think that can be a good thing. It gives you the freedom to write the story inside of you. As writers, we have to let go of the things we have no control over – like shifting markets. We have to focus on what we do control. So push those little doubtful voices out of your head. Make your manuscript the best story you can write and then send it out into the world. Once you have, start writing your next great story. Take each hurdle as it comes and don’t give up until you’ve reached your goal.

-- Lisa

About the Author:

Lisa works full-time as a freelance writer and editor of curriculum materials. She is also the author of a dozen books for the school and library market. Her personal goal at the moment is to have three days in a row where everything on her to-do list actually gets done. PROVIDENCE is her first trade novel.

Website | Twitter | Goodreads

About the Book:

About the Book:

Providence – Sometimes you have to run away from home to find it.

Teen runaway Becky is hiding out with a baby who isn’t hers. Although she found newborn Georgia in a duffle bag in a train car, Becky is as fiercely protective of her as if she were her own.

In the small town where she passes for a teen mom, she finally happy. Then, people start to ask questions, and Becky doesn’t know whether to stay and fight, or run toward an unknown future.

Amazon | Goodreads

GIVEAWAY! WIN A COPY OF THE BOOK

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Point of View, POV, Craft of Writing, Nikki Kelly, Add a tag

Viewpoint Selection by Nikki Kelly

“Hi Nikki, I need your help! I have a story that I want to write but I’m a bit confused, I don’t know which point of view I should tell it from. How did you pick? What made you write your story from Lailah’s POV??? Please could you help me! I really want to get started but I don’t know what to do!”I originally posted my debut novel Lailah to wattpad, a community of readers and writers, back in December 2012. I am still very active on the platform and talk to young, aspiring writers every day. The above question hit my inbox a couple of weeks ago, but it’s not the first time I have been asked about viewpoint selection, and I’m sure it won’t be the last.

This question almost, always includes these exact words—‘which point of view is the right one?’

The answer, I say… well, there is no right answer.

I usually begin my reply by breaking down the most common, and simple, viewpoints:

First Person

Writing as if you are the character: I, me, my.

Third Person, limited

Writing with: he, she, they and pronouns such as his, hers, theirs.

Maintaining the narrative to the feelings, and ponderings of only the viewpoint character.

Third Person, omniscient

Still writing with: he, she, they and pronouns such as his, hers, theirs.

This time, however, the narrator is ‘all knowing’ of all the characters thoughts and feelings. Omniscient gives a broader view of the story.

I go on to highlight that there are Pros…

…and Cons

…to writing in each viewpoint:

First Person, the Pros include:

The reader has an immediate connection to the viewpoint character.

Believability due to being ‘inside’ the viewpoint character's head.

Clear, and concise perspective.

First Person, the Cons include:

Your reader can only know what your viewpoint character knows.

Limited perspective.

If your viewpoint character is unlikable, you have to live in his/her head for as long as it takes you to tell the story!

Third Person, limited, the Pros include:

Can add suspense as the thoughts and feelings of the other characters remain unknown (only interpreted through the viewpoint character).

Can still connect closely with the viewpoint character.

Third Person, limited, the Cons include:

As with first person, the perspective is limited and your reader can only know what your viewpoint character knows.

Third Person, omniscient, the Pros include:

Can connect with more characters in the story in a more intimate way.

Easier to manipulate the plot as there are more choices and options available.

Greater flexibility.

Third Person, omniscient, the Cons include:

The reader has more distance from your viewpoint character.

Multiple characters thoughts and feeling to juggle

I check in and ask if that all makes sense…

So then I suggest writing a paragraph from the story using all three viewpoints, and reading each one aloud. This helps to see which viewpoint comes most naturally when writing, and also helps to establish which works best for the story you are trying to tell.

Often, this then leads to…

I chose to write my debut novel Lailah in first person, as it came more naturally, and it worked well for the story itself. Lailah is on a journey of self-discovery, and I wanted the reader to only know what she knew, to learn the truth of Lailah’s undiscovered nature, right along with her. This also worked really well for the reveals (there was, of course, some bread crumb dropping along the way!), and it worked especially well for the plot twists at the end of the book.

About the Author:

Nikki Kelly was born and raised only minutes away from the chocolately scent of Cadbury World in Birmingham, England. Lailah is Nikki's first novel, and the first book in the Styclar Saga. She lives in London with her husband and their dogs, Alfie (a pug) and Goose (a chihuahua).

Visit her online at www.thestyclarsaga.com

Twitter: @Styclar

Goodreads

About the Book:

LAILAH (The Styclar Saga #1)

Nikki Kelly

The girl knows she’s different. She doesn’t age. She has no family. She has visions of a past life, but no clear clues as to what she is, or where she comes from. But there is a face in her dreams – a light that breaks through the darkness. She knows his name is Gabriel.

On her way home from work, the girl encounters an injured stranger whose name is Jonah. Soon, she will understand that Jonah belongs to a generation of Vampires that serve even darker forces. Jonah and the few like him, are fighting with help from an unlikely ally – a rogue Angel, named Gabriel.

In the crossfire between good and evil, love and hate, and life and death, the girl learns her name: Lailah. But when the lines between black and white begin to blur, where in the spectrum will she find her place? And with whom?

Gabriel and Jonah both want to protect her. But Lailah will have to fight her own battle to find out who she truly is.

Amazon | Indiebound | Goodreads

Blog: From the land of Empyrean (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: mermaids, inspirational, POV, Walt Disney World, Mark Miller, Helping Hands Press, monorails, twine ball, writer, point of view, writing, fantasy, Add a tag

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Sarah Skilton, Point of View, Add a tag

In BRUISED, my contemporary Young Adult novel, the narrator is 16-year-Imogen, a black belt in Tae Kwon Do who freezes up at an armed robbery and is left to wonder if martial arts failed her or she failed it.

In BRUISED, my contemporary Young Adult novel, the narrator is 16-year-Imogen, a black belt in Tae Kwon Do who freezes up at an armed robbery and is left to wonder if martial arts failed her or she failed it. Because Imogen's identity is so wrapped up in her martial arts abilities, her failure to use those abilities when it really matters destroys her in a way it wouldn't destroy someone else, someone who hasn't spent the last six years training four times a week and dreaming of opening her own martial arts school one day.

Because Imogen's identity is so wrapped up in her martial arts abilities, her failure to use those abilities when it really matters destroys her in a way it wouldn't destroy someone else, someone who hasn't spent the last six years training four times a week and dreaming of opening her own martial arts school one day.Sarah Skilton lives in Southern California with her husband and son. She has studied Tae Kwon Do and Hap Ki Do, both of which came in handy while writing her martial arts-themed debut YA novel, BRUISED, available now from Amulet Books along with her second book, HIGH AND DRY.

*originally posted on Paranormal Point of View

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: stand alone, point of view, character, Plot, series, how to write, trilogy, Novel Revision, Add a tag

|

|

|

To write a series of books, my biggest tip is to plan ahead. You may get by with writing one book on the fly—plenty of people do that. But for a series to hang together, to have cohesion and coherence, planning is essential. Here are three decisions you should make early in the planning process.

Decision #1: What type of series will you write?

Strategies for a series vary widely. For THE HUNGER GAMES, the story is really one large story broken down into several books. Or, to say it another way, there is a narrative arc that spans the whole series. Yes, each book has a narrative arc and ends on a satisfying note; however, we read the next book because we want to know what happens in the overall series arc. Jim Butcher’s ALERA CODEX is another series with an overall series arc; it was fun to hang out in this world for a long time.

On the other hand, series such as Agatha Christie mysteries (in fact, many mystery series fall into this category) are stand-alone books. What continues from one book to the next is the characters, the setting and milieu, and the general voice and tone of the stories. Once a reader gets to know a character, s/he wants to spend more time with that character. These readers just want to hang out with a friend, your character. A sub-category is the series of standalone books that adds a final chapter to set up the next book in the series and leaves you with a cliff-hanger.

I distinctly remember when I first read Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter series about Mars. Each story is a standalone novel, but he hooked me hard. I started reading at noon on a Saturday and found myself hotfooting it to the bookstore at 4:30 pm because they closed at 5 pm and I had to have the second book to read immediately.

Rarer is the series that crosses genres. This type series begins with one genre, but moves into other genres as the lives of the characters progress. For example, a romance might continue with a mystery for the second book. And the third might move into a supernatural genre. These are rarer because one reason a reader sticks with a series is that they know what they are getting. It will be this type of a story, told in this sort of way and will involve these characters.

On the other hand, some series unabashedly cross genres but they do it for every book. Rick Riordian’s Percy Jackson series is a combination of mythology and action/thriller with a dose of mystery.

Notice that this decision centers on the plot of the stories in the series. Will you plot each separately, or will there be an overall plot?

Decision #2: Characters

Besides plot, you should make decisions about characters, and as with plot, you have choices. One choice is an ensemble cast that will carry over from book to book. Here, you have Percy Jackson, his friends and his family as constants. Each book introduces new characters, of course, but there is a core that stays the same.

Another option is to have just one character remain the same. Agatha Christie had Hercule Poirot traveling around and the only constant was the gumshoe and his skills.

Whether you choose one character or an ensemble, you can add or subtract as you go along. But the characters must be integral to the story’s plot.

In developing series characters, think about cohesion and coherence.

Cohesion: Elements of the story stick together, giving cohesion. For example, if one alien in the family can use telekinesis (moving objects with your mind), then that possibility should exist for all members of the family. Of course, some might not have the power, or it may develop slowly for a child, but the possibility should exist.

Coherence: Elements of a story are consistent from book to book. If Kell’s eyes are silvery in book one, they are silvery in books two, three and four.

Decision #3: How long do you want the series to continue?

Many easy readers series go on forever. Think of THE BERENSTAIN BEARS, who continue their adventures and lives throughout multiple volumes. For this type series, the story possibilities are endless. Or think of a TV series, where the situation set up is rich with possibilities. I Love Lucy ran for years and years on the premise of a slightly crazy wife of a musician.

On the other hand, some series have a finite life span. For stories with a narrative arc that spans a series, the life span is built into the plot. However even for these, there can be spin-offs into related series. Think of Percy Jackson and the Olympians series and Heroes of Olympia series. The A to Z Mysteries by Ron Roy and John Gurney had a built-in limit of 26 books.

Sometimes, the length of a series depends on the publisher and the early success of the series titles. When Dori Hillestad Butler’s first book in The Buddy Files series, THE CASE OF THE LOST BOY, won the 2011 Edgar Award for the best juvenile mystery of the year, the publisher contracted for more.For Sara Pennypacker, author of the CLEMENTINE series of short chapter books, the answer of series length depended on something else. In a presentation about writing, she said that she had to ask herself what she wanted to say to third graders. She came up with eight things. Pennypacker focused on the themes of each book (friendship, telling the truth, etc) and found that eight was the natural stopping place for her. Of course, she reserves the right to many more, if other themes present themselves. But she deliberately stepped away from doing a Christmas book, a Halloween book, a 4th of July book, a fall book, a back-to-school book and so on and so forth.

My books, THE ALIENS, INC. SERIES, just released in August, 2014, is about an alien family that is shipwrecked on Earth and must figure out how to make a living. It’s been interesting developing these stories and thinking about these three issues.

My books, THE ALIENS, INC. SERIES, just released in August, 2014, is about an alien family that is shipwrecked on Earth and must figure out how to make a living. It’s been interesting developing these stories and thinking about these three issues.

They accidentally fall into party planning and each book features a different type of party or event put on by Aliens, Inc, the family’s company. KELL, THE ALIEN, the lead-off story, is about a birthday party and of course, it is an alien party. Can the aliens pull off an alien party? The second is about a Friends of Police parade, entitled, KELL AND THE HORSE APPLE PARADE. Book 3, KELL AND THE GIANTS, explored the world of tall and how to keep a giant secret.

Can you tell just from the description some of the decisions I made? There isn’t an overall series arc. Rather, the characters, setting and milieu are set up and there could be endless stories in the series. However, like Butler’s dog mystery series, I am starting with four books and their success will determine future titles. There is a main character who is surrounded by friends and family and, of course, a villainess. These characters weave through the stories and provide cohesion and coherence.

Plan ahead and your series will be stronger. For those who accidentally fall into a series, it will be harder to sustain coherence. You may realize in book three that it sure would be nice if your character had to wear glasses. Yes, you can add it—but you run the danger of it being obviously done for the story itself. So, in my series, early readers have questioned things like the art teacher who is from Australia.

They ask, “Does it matter that she is from Australia?”

“Not yet,” I answer. I just know that I have seeded these early manuscripts with possibilities. If the series goes to books 5-8, I will have hooks to draw upon. So, while I haven’t plotted those books, I have still allowed room for them.

Resource: Writing the Fiction Series: The Complete Guide for Novels and Novellas by Karen S. Wiesner (Writer’s Digest Books)

Want to write a series? What is your favorite series and how will your stories compare?

Blog: Cupcake Speaks (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: kidlit, point of view, writing, children's literature, character, picture book writing, countdown, writing class, 12x12, Add a tag

Today, Mom and I are counting down about advice.

Advice I Get

3. Be Quiet – Mom says this word when the mailman comes. Ditto the FedEx and UPS guys. She clearly does not know these people are here to kill me. I must sound the alarm.

2. Don’t pull – Mom tells me this word when I am smelling delicious things outside, and checking my pee-mail. She clearly does not know that if I don’t quickly eat the goose candies in the grass, one of my dog friends might get them and I will miss out.

1. Fetch it – It took me a long time to understand this advice. I finally learned what it means. For any of my friends struggling with fetching, the secret to it is the bring-back. Do not get the ball, bring it on the couch, and try to hatch it like an egg.

That is apparently not fetching. Bring it back to Mom and GET A TREAT. That’s fetching.

Advice Mom Gets

3. Add Conflict – People don’t like conflict. Especially Mom. But in a story, conflict is good. So are suspense, action, problems, unexpected obstacles, surprises, and other kinds of trouble. I like trouble.

2. Find Your Voice – Each time she starts a new story (at least once a month), Mom has to find her picture book voice. Voice helps the book sound unique and different from other books. Voice shows Mom’s characters looking at the world in their own special way.

1. Focus on Character – Mom usually writes stories that are plot, plot, plot. Lately, she is trying to take the advice she’s received about developing character, character, character. Susanna Hill’s Picture Book Magic class helped her a lot with that. Now Mom can get to know her characters before they start living in her story.

Speaking of living, two of my bloggy friends gave me the Sunshine Award, recently. I think it’s the perfect time of year for this award, since the snow is finally gone, and any minute now, the sun will shine and I will take a street nap.

A big, sunny thank you to Collies of the Meadow and The Squeak Life for sharing this prize with me. If you feel like you need a smile, visit them. They’re a guaranteed giggle. And if you want to celebrate the sunshine, take this award and post it to your own blog.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: revise, dramatic, stream of consciousness, monologue, how to create, omniscience, story, novel, point of view, character, Characters, characterization, Add a tag

Now available!

How does an author take a reader deeply into a character’s POV? By using direct interior monologue and a stream of consciousness techniques.

This is part 3 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside Outside/Inside Inside

Going Inside a Character’s Head, Heart and Emotions

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Omniscience.Jauss says, “In direct interior monologue, the character’s thoughts are not just ‘reflected,’ they are presented directly, without altering person or tense. As a result, the external narrator disappears, if only for a moment, and the character takes over as ‘narrator.’” (p. 51)

Here, “. . . the narrator is not consciously narrating.” In much of IVAN, he is consciously narrating the story. Sometimes, it might be hard to distinguish the difference because the character and narrator are the same, and it’s written in present tense (except when he is telling about the background of each animal). This closeness of the character and narrator is one reason to choose first-person, present tense. But there are still times when it is clear that IVAN is narrating his story.

But there also times when that narrator’s role is absent. In the “nine thousand eight hundred and seventy-six days” chapter, Ivan is worried about what Mack will do after the small elephant Ruby hits Mack with her trunk:

“Mack groans. He stumbles to his feet and hobbles off toward his office. Ruby watches him leave. I can’t read her expression. Is she afraid? Relieved? Proud?”

The last three questions remove the narrator-Ivan and give us what Ivan is thinking at the moment. The direct interior monologue gives the reader direct access to the character. With a third person narrator, those rhetorical questions might be indirect interior monologue; but here, because of the first person narration, it feels like direct interior monologue.

Or, in the “click” chapter, Ivan is about to be moved to a zoo:

The door to my cage is propped open. I can’t stop staring at it.

My door. Open.

The first two sentences still feel like a narrator is reporting. But “My door. Open.” feels like direct access to Ivan’s thought at that precise moment. He’s not looking back and reporting, but this is direct access to his thoughts.

A last technique for diving straight into a character’s head is stream-of-consciousness. Jauss says, “. . . unlike direct interior monologue, it presents those thoughts as they exist before the character’s mind has ‘edited’ them or arranged them into complete sentences.” (P. 54)

When Ivan is finally in a new home at a local zoo, he is allowed to venture outside for the first time. The “outside at last” chapter is stream-of-consciousness.

Sky.

Grass.

Tree.

Ant.

Stick.

Bird. . . .

Mine.

Mine.

Mine.

What the reader feels here is Ivan’s wonder at the great outdoors. It’s a direct expression of Ivan’s joy in being outside after decades of being caged. We are one with this great beast and it gives the reader joy to be there.

Or look at the “romance” chapter, where Ivan is courting another gorilla.

A final note: Sometimes, an author breaks the “fourth wall,” the “imaginary wall that separates us from the actors,” and speaks directly to the reader. This is technically a switch from 1st person POV to 2nd person POV. But it is very effective in IVAN in the second chapter, “names.” Here, Ivan acknowledges that you—the reader—are outside his cage, watching him. It was a stunning moment for me, as I read the story.

“I suppose you think gorillas can’t understand you. Of course, you also probably think we can’t walk upright.

Try knuckle walking for an hour. You tell me: which way is more fun?”

Do stories and novels have to stay in one point of view throughout an entire scene or chapter? No. Not if you are thinking about point of view as a technique to draw the reader close to a character or shove the reader away. You can push and pull as you need. You can push the reader a little way outside to protect his/her emotions from a distressing scene. Or you can pull them into the character’s head to create empathy or hatred. You can manipulate the reader and his/her emotions. It’s a different way of thinking about point of view. For me, it’s an important distinction because my stories have often gotten characterization comments such as , “I just don’t feel connected to the characters enough.” I think a mastery of Outside, Outside/Inside, and Inside point of view techniques holds a key to a stronger story.

In the end, it’s not about the labels we apply to this section or that section of a story. These techniques can blur, especially in a story like IVAN, written in first person, present tense. Instead, it’s about the reader identifying with the character in a deep enough way to be moved by the story. These techniques–such a different way to think about point of view!–are refreshing because they give us a way to gain control of another part of our story. These are what make novels better than movies. I’ve heard that many script-writers have trouble making the transition to novels and this is the precise place where the difficulty occurs. Unlike movies, novels go into a character’s head, heart and mind. And these point of view techniques are your road map to the reader’s head, heart and mind.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series

Outside Outside/Inside Inside

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: story, novel, point of view, character, Characters, characterization, revise, dramatic, stream of consciousness, monologue, how to create, omniscience, Add a tag

Now available!

Partially Inside a Character’s Head: OUTSIDE AND INSIDE POV

How deeply does a story take the reader into the head of a character. Many discussions of point of view skim over the idea that POV can related to how close a reader is to a reader. But David Jauss says there are two points of view that allow narrators to be both inside and outside a character: omniscience and indirect interior monologue.

This is part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

- Outside

- Outside/Inside

- Inside

These posts are inspired by an essay by David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft. I am using Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

Omniscience. Traditionally, “limited omniscience” means that the narrator is inside the head of only one character; “regular omniscience” means the narrator is inside the head of more than one character.

I love Jauss’s comment: “I don’t believe dividing omniscience into ‘limited’ and regular’ tells us anything remotely useful. The technique in both cases is identical; it’s merely applied to a different number of characters.”

He spends time proving that regular omniscience never enters into the heart and mind of every character in a novel. A glance at Tolstoy’s WAR AND PEACE, with its myriad of characters is enough to convince me of this truth.

Rather, Jauss says the difference that matters here is that the omniscient POV uses the narrator’s language. This distinguishes it from indirect interior monologues, where the thoughts are given in the character’s language. This is a very different question about POV: is this story told in the narrator’s language or the character’s language?

In IVAN, this is an interesting distinction because Ivan is the narrator of this story; it’s told in his voice. But as a narrator, there are times when he drops into omniscient POV. In the “artists” chapter, Ivan reports:

“Mack soon realized that people will pay for a picture made by a gorilla, even if they don’t know what it is. Now I draw every day.”

Ivan tells the reader what Mack is thinking (“soon realized”) and even what those who purchase his art are thinking (“even if they don’t know what it is”). Then, he pulls back into a dramatic reporting of his daily actions. Notice, too, that he makes this switch from dramatic POV to omniscient POV within the space of one sentence. And the omniscient POV dips into two places in that sentence, too.

Because Mack is Ivan’s caretaker and has caused much of Ivan’s troubles, the reader needs to know something of Mack’s character. This inside/outside level is enough, though. The author has decided that a deep interior view of Mack’s life isn’t the focus of the story. It’s enough to get glimpses of his motivation by doing just a little ways into his head.

Indirect Interior Monologue

Another technique for the narrator and reader to be both inside and outside a character is indirect interior monologue. Here, Jauss says that the narrator “translates the character’s thoughts and feelings into his own language. “ (p. 45) The character’s interior thoughts aren’t given directly and verbatim. This is a subtle distinction, but an important one.

Interior indirect monologue usually involves two things: changing the tense of a person’s thoughts; and changing the person of the thought from first to third. This signals that the narrator is outside the character, reflecting upon the character’s thoughts or actions.

They are all waiting for the train. (dramatic)

They were all waiting reasonably for the train. (Inside, indirect interior monologue)

The word “reasonably” puts this into the head of the narrator, who is making a judgment call, interpreting the dramatic action.

Interior indirect monologue most often seen with a third-person narrator reflecting another character’s thoughts. But in Ivan, we have a first-person narrator. Applegate stays strictly inside Ivan’s head, except for a few passages where Ivan reports indirectly on another character’s thoughts. Because the passages are already in present tense, she doesn’t have that tense change to rely on.

Here’s a passage that could have been indirect interior monologue but Applegate won’t quite go there. Stella is an elephant in a cage close to Ivan.

“Slowly Stella makes her way up the rest of the ramp. It groans under her weight and I can tell how much she is hurting by the awkward way she moves.”

By adding “I can tell. . .” it stays firmly inside Ivan’s head. He tells us that this is true only because Ivan makes an observation. The story doesn’t dip into the interior of the other characters.

But there are tiny places where the interior dialogue peeks through. This from the “bad guys” chapter. Bob is Ivan’s dog friend; Not-Tag is a stuffed animal; and Mack is Ivan’s owner.

“Bob slips under Not-Tag. He prefers to keep a low profile around Mack.”

Ivan can only know that Bob “prefers” something, when he, as the narrator, dips into Bob’s thoughts.

But indirect interior monologue is also used by a first person narrator to report his/her prior thoughts. When the first person narrator tells a story about what happened in his past, he is both the actor in the story and the narrator of the story. Ivan tells the story of his capture by humans over the course of several short chapters. It begins in the “what they did” chapter:

“We were clinging to our mother, my sister and I, when the humans killed her.”

While Ivan’s story is most present tense, this is past tense because Ivan is reporting on prior events. Even here Applegate refuses to slip into interior indirect monologue. Instead, she just presents the facts in a dramatic manner and lets the reader imagine what Ivan felt. It’s interesting that withholding Ivan’s thoughts here evoke such an emotional response in the reader.

On the other hand, in “the grunt” chapter, Ivan tells about his family. Again, he is the narrator telling about a past event when he was a main character of the event:

“Oh, how I loved to play tag with my sister!”

This could be called direct interior thought, but because he’s narrating a past event, it’s indirect interior thought. Otherwise, he would say, “Oh, how I love to play tag with my sister!”

Or from the “vine” chapter, where Ivan talks about his thoughts after being captured by humans:

“Somehow I knew that in order to live, I had to let my old life die. But sister could not let go of our home. It held her like a vine, stretching across the miles, comforting, strangling.

We were still in our crate when she looked at me without seeing, and I knew that the vine had finally snapped.”

If this was direct interior, it would be:

“Somehow I know that in order to live, I must let my old life die.”

Applegate could have chosen to stay inside Ivan, but here, she pulls back so the reader isn’t fully inside this emotionally disturbing moment. She uses indirect interior monologue, instead of direct.

As Jauss says about a different passage, but it applies here, “This example also illustrates the extremely important but rarely acknowledged fact that narrators often shift point of view not only within a story or novel but also within a single paragraph.” (p.50)

This has been proclaimed a mistake in writing point of view, but Jauss says it’s a normal technique. We dip into Mack’s point of view, but then pull back to a dramatic statement about what Ivan is doing.

Indirect interior monologue often includes “rhetorical questions, exclamations, sentence fragments and associational leaps as well as diction appropriate to the character rather than the narrator. “ (p. 49) In one of my novels, I used a lot of rhetorical questions as a way to get into the character’s head and an editor complained about it. Now, that I know why I was using it (as a way to manipulate how close the reader was to the character), I could go back and use a variety of techniques. Knowledge of fiction techniques is freeing! Tomorrow, we’ll look at how to go deeply into a character’s head, heart and emotions.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Join us tomorrow for the final part of the series, Inside: Going Deep into a Character’s Head.

This has been part 2 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Inside: Deeply Inside a Character’s Head. Read the whole series.

Outside Outside/Inside Inside

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: direct interior monologue, point of view, character, Characters, stream of consciousness, create a character, Add a tag

Now available!

A story’s point-of-view is crucial to the success of a story or novel. But POV is one of the most complicated and difficult of creative writing skills to master. Part of the problem is that POV can refer to four different things, says David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

Definitions of Point of View

- Your personal opinion. You might say, “From my point of view, that’s wrong.”

- The narrator’s person: 1st, 2nd, or 3rd.

- The narrative techniques: “omniscience, stream of consciousness and so forth”

- “. . .the locus of the perception (the character whose perspective is presented, whether or not that character is narrating)” (p. 25)

The first definition is a personal, not a literary one, so it doesn’t apply here. The second definition (the narrator’s person) is perhaps the most widely discussed, but Jauss says it isn’t helpful to a writer as s/he approaches a story. In fact, what often happens is these definitions collide and the generally accepted wisdom is that you must stay in only one POV, you can’t use some techniques in some POVS, and the narrator is a side-issue. These conventional rules, though, conflict with actual practice, says Jauss. Further, they prevent writers from controlling one of the most important aspects of fiction: how close the reader feels to the characters. (p. 26, 36)

I love the idea that point of view is a technique: it is one of the tools in our writer’s tool box that we can pull out as needed to accomplish something in a story. I love the idea that point of view allows you to pull the reader closer to the characters or to shove them away from the character. Right away, Jauss has me. And it only gets better from here. More complicated, but better.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Traditional Point of View

Jauss points out that traditionally point-of-view is discussed in terms of person, and defined by the pronouns used.

First person uses I, me, my, myself and so on; the story is told from inside the narrator’s head and the reader is privy to all the narrator’s thoughts and emotions.

Third person uses he, she, they and so on; the story is told as if there was a camera above the narrator’s head and the reader knows only what the narrator sees. A close third person allows the narrator’s thoughts and emotions to be conveyed to the reader.

Second person is seldom used and talks directly to the reader using you as the main pronoun.

POV techniques include the omniscient POV, which dips into different character’s heads to give the reader a look at the thoughts and emotions of multiple characters; the camera can change from one reader’s head to another, as the story demands.

Point of View as Technique for Getting into a Character’s Head

Point of view, according to Jauss, should be classified by how far into the character’s heads the reader is allowed to go. He proposes a continuum from fully Outside POV, to a POV that is both Outside and Inside and finally a POV that is fully Inside.

Outside, Outside & Inside and Inside. That’s the three new categories of POV. Jauss gives examples of these POV from what we would traditionally call first-person and third-person POV; I’ll be giving examples from the “first-person” book, Ivan, the One and Only. Ivan is undoubtably written in what most would call 1st person POV. The silverback gorilla, Ivan, is narrating the entire story. As such, it has a simple vocabulary and uses simple sentence structure to match the intelligence of an animal; but this animal has a big heart and that’s where technique allows the writer to manipulate how close the reader comes to the character.

OUTSIDE POV: What the Reader Infers about Character

Dramatic. Jauss says, “There is only one point of view that remains outside all of the characters, and that’s the dramatic point of view. . .”

Jauss defines this as a story in which the narrator is telling a story from outside all the characters AND uses language unique to the narrator. Notice that for Jauss, the narrator is an important part of distinguishing the POV technique used.

Dramatic storytelling is the the traditional show-don’t-tell kind of storytelling, where some insist that you must show everything and the reader should understand the action and emotions simply from what is shown.

In the “Bob” chapter of IVAN, we find an example of this, where a small dog interacts with the gorilla:

“He hops onto my chest and licks my chin, checking for leftovers.”

Even though the narrator is Ivan and he is including himself in the action, it is still dramatic action. Nothing in this statement gets inside of Ivan’s head; it’s purely dramatic. In fact, most of the “Bob” chapter is dramatic telling from Ivan’s point of view. He dips into his own feelings (indirect or direct interior dialogue—see discussion later) a few times, but it’s mostly dramatic.

One common demand for a dramatic POV is that the reader understand the character’s emotions only from the actions. If angry, a character might tighten his fists, or his brow might furrow, or he may bare his teeth. Jauss says “the story that results is inevitably subtle. Careless or inexperienced readers will often be confused by stories employing this point of view.” (p. 40)

What a breath of fresh air! Some writing teacher emphasize this Show-Don’t-Tell to the extreme and yet Jauss says the results are “inevitably subtle.” Because I write for kids, I must question whether “subtle” is what I want! I’ve long thought that the Show-Don’t-Tell is more a plea for stronger sensory details than for implied emotion, and have modified it to say, Show-Then-Tell-Sometimes. What I mean is that the sensory details should put the reader into the situation; but after you’ve done that, sometimes you must interpret the actions for the reader.

“Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That uses sensory details; it shows, and doesn’t just tell. But we don’t know WHY Jill slaps Bob. Did she do it to wake him up after he passed out?

“Desperate, Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That word, “desperate,” pulls the sentence out of a strictly dramatic telling and starts to drill down into Jill’s emotions. However, we need that word in order to understand the story.

This technique isn’t used extensively throughout IVAN, but here’s one example. The small elephant, Ruby, is watching the older elephant Stella do her tricks with Snickers the circus dog.

“Ruby clings to her like a shadow. Ruby’s eyes go wide when Snickers jumps on Stella’s back, then leaps onto her head.”

We aren’t TOLD that Ruby is scared of the dog; instead, “Ruby’s eyes go wide.” The reader must infer Ruby’s emotions from that bit of action. And here, it works well. We don’t need an extra adjective for interpretation. Applegate does an amazing job of walking this fine line and keeping the action strictly dramatic.

Dramatic storytelling is like watching a play on stage, or watching a movie. We can never go deeper into a character’s point of view, because the camera can’t go inside a character. The closest we can come is the constant monologues that are a technique of reality TV, where a character talks to the camera and interprets a sequence of actions or explains their thoughts during a sequence. Even that doesn’t take you inside the character like the next techniques can. For the Outside/Inside techniques, join us tomorrow.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Outside/Inside: Partially Inside a Character’s Head

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: point of view, plot, subplot, first draft, chase, how to write a novel, Add a tag

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Start Your Novel

by Darcy Pattison

Giveaway ends October 01, 2013.

See the giveaway details at Goodreads.

My current WIP novel has a subplot of a chase, which is one of the 29 possible plot templates. Chase Plots are pretty straight forward. There’s a person chasing and a person being chased, the Chaser and the Victim. It’s an action plot, not a character plot (though always, character should be as strong as possible.)

The Chase plot has one major imperative: The Chaser must constantly catch sight of the Victim and the Victim always escapes by the narrowest margin. Otherwise, it’s boring. This subplot must tantalize the reader with the possibility of Chaser actually catching Victim.

My first draft of chapter one completely omitted the Chase subplot, so the first revision I did was to revisit the idea of a Chase Subplot. Yes, the story still needs it. Then, I had to decide how to add in the Chase subplot in an exciting way. What could I add that would give the Chaser a glimpse of her target? My twist on the Chase Plot is the Chaser doesn’t always recognize the Victim. So, I gave Chaser a smart phone app that identifies the Victim. Now, Chaser walks up to a table where Victim is sitting and the app starts to go off, but. . .Chaser is interrupted.

The Car Chase is a staple of Chase Plots. You can choose any form of chase, though, and still up the tension of your story.

Victim is almost caught and only escapes by chance. Because the story is in Victim’s point of view, this works because Victim realizes the danger he was in. Chaser is still clueless, of course, but that’s OK, because it’s not her POV.

Having a chance escape also works this initial time, because the scene introduces the rules of the Chase scene. But now, Victim KNOWS there’s a smart phone app and will have to use his ingenuity to stay out of range of that app. It will, of course, be easier said than done.

The whole scene has upped the stakes in the story as a whole. The other subplots are now free to carry on as needed, because at the right moments the Chase Subplot will be there to add to the story’s tension. Will Chaser actually CATCH Victim? Who know? Stay tuned!

What subplot(s) are you adding to you story to keep the tension high?

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: point of view, character, characters, POV, hero, villain, Add a tag

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

Question: How do you tell a story and make sure that both sides get heard?

Answer: This is a time when switching point-of-view might be helpful.

The default for telling a story is 3rd-person point-of-view. You tell it like you are recording from a camera that sits right above the point-of-view (POV) character’s head. Usually the POV character is the main character, but it can be a friend or some other character. The key is the pronouns: you use he, she, they, them.

If the camera is above the character’s head, you can’t tell what the character is thinking. That’s 1st person POV, which uses I, me and my pronouns. There is a close 3rd person POV which lets you imply the character’s thoughts.

1st: I sift through photos until–I stop and hold up THE photo. It shows me, sitting on my Dad’s lap. I was just five and it was the day before he disappeared.

3rd: She shifted the photos, one by one. Then she held one up and shifted to let the light fall on it better. Yes, it was Dad and she was sitting on his lap. She remembered that day because it was the day before her Dad disappeared.

Which do you like better? It’s a personal thing in some respects and also a question of which one serves your story better.

But back to the question: How do you make sure both sides get heard? Usually, you’ll create a story with two POV characters, one the hero(ine) and one the villain(ess). POV switches typically happen at chapter breaks, that is you’ll have one chapter from the Hero(ine)’s POV, then a chapter from the Villain(ess)’s POV. You can alternate as needed and you don’t have to make it evenly split between the two POV.

The advantage of this is that you can explain the deep issues that each character has from their POV. The difficulty of this is creating two characters that the audience will truly care about and will root for. You want the audience to like the characters. Is your villain a likeable sort? Or at least a sympathetic sort?

Also, consider what the audience will know if you use this strategy. The reader will be in on every nuance of the villain’s plans. How will you create surprise? You can build suspense, which is slightly different. For suspense, the reader knows something will happen and hopes against hope that the character will avoid the problem. That sort of thing will work with an alternating chapter strategy.

Sometimes, the POV switch will take place within a chapter, but usually, the sections are set off somehow, maybe an extra space or asterisks or other visual cues that something has changed.

What rarely works is changing within a paragraph.

In the end, how do you know if alternating chapters will work? You try it out.

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Craft, Story Structure, Storyteller, Narrator, Story Design, Organic Architecture, Designing Principle, Point of View, Add a tag

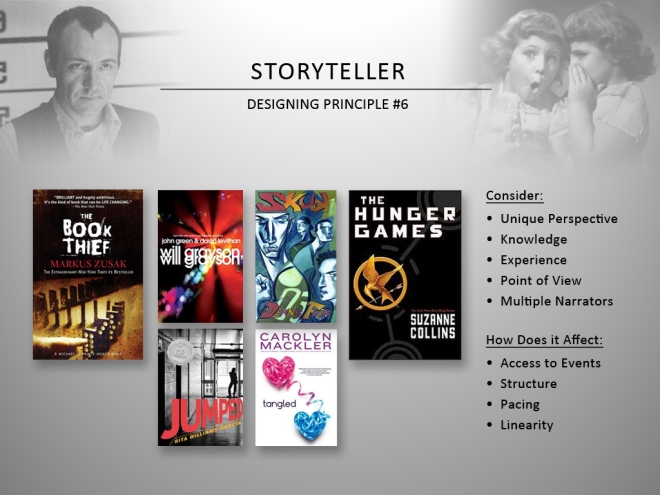

The final category in my series on designing principles is the storyteller.

Who is your novel’s storyteller?

At the outset, it might not seem like the point-of-view or the narrator you chose to tell your story would have a large impact on its structure, but it does. Imagine if how differently the The Usual Suspects would be if it wasn’t told from the POV of Kevin Spacey’s character sitting in a New York City police station. Or imagine how the design of The Book Thief would be different if it wasn’t narrated by death. Or how the structure of The Hunger Games changes when you move out of the first person narration of Katniss’ mind in the book, to the omniscient eye taken in the movie? The choices of what is put where, and why, changes.

Additionally, consider the design effect of having multiple POV narrators as done in the book Will Grayson, Will Grayson which has two narrators, or Jumped which has three, or Tangled which has four, or Keesha’s House which has eight. How does one move from POV to POV? By alternating chapters? By telling the whole story of one and then the whole story of another? Or maybe weighing the POV of one over another?

The storyteller of your book is going to affects it pacing, its linearity, its patterns of repetition, and the breadth of knowledge and experience the storyteller has access to. It has ramifications in all your other design choices and shouldn’t be chosen lightly.

Hopefully, these six categories have helped you to think about how to structure and plot your own novel in a way that is organic, instead of plugging your characters in to a pre-designed template. Have fun exploring all the alternate plots and structures at your fingertips, and remember that using them should come organically from your premise and characters!

I know this has been a long series (thanks for hanging in there with me). I’ve only got a few final notes before wrapping it all up.

Up Next: Structural Layering (because yes, you probably won’t pick one structure and be done!)

Want to know more about designing principles? Try these links:

- What is a designing principle?

- Designing principle #1: A character’s mental state

- Designing principle #2: Setting and environment

- Designing principle #3: Time

- Designing Principle #4: Community

- Designing Principle #5: Parallel stories and myth

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: how to create, fiction, novel, point of view, creative writing, character, characters, attitude, prompts, Add a tag

2013 GradeReading.NET Summer Reading Lists

Keep your students reading all summer! The lists for 2nd, 3rd and 4th, include 10 recommended fiction titles and 10 recommended nonfiction titles. Printed double-sided, these one-page flyers are perfect to hand out to students, teachers, or parents. Great for PTA meetings, have on hand in the library, or to send home with students for the summer. FREE Pdf or infographic jpeg.

See the Summer Lists Now!

Keep your students reading all summer! The lists for 2nd, 3rd and 4th, include 10 recommended fiction titles and 10 recommended nonfiction titles. Printed double-sided, these one-page flyers are perfect to hand out to students, teachers, or parents. Great for PTA meetings, have on hand in the library, or to send home with students for the summer. FREE Pdf or infographic jpeg.

See the Summer Lists Now!

You know you should try writing your story in first v. third point of view, but for some reason, you put it off. Why? Because you’ve gotten a first draft of a scene or chapter and you just want to keep going.

It’s exactly the feeling that elementary school children have: “Why do I have to revise?”