A few weeks ago, I was at Georgia State's College of Education to talk with professors and students about Native peoples, how we're taught in the curriculum, choosing children's books, etc. A few days ago, a student wrote to me with a question about biased content and how a teacher could address it.

She had a specific example in which she imagined a fourth grade class being taught about specific Native Nations. She imagined a student asking the teacher why Native Americans were moved to reservations. She wondered how the teacher might respond in an unbiased manner.

Let's look, first, at the word "bias." It means prejudice in favor or against a thing, person, or group, compared with another, in a way that is unfair or partial to one of the groups.

A couple of weeks ago, I noted that I was reading Deborah Wiles's Revolution. There's a passage in it that is a good example of bias. On page 263, Sunny (the protagonist) is at a movie theater and is approaching Mr. Martini, the man who takes tickets:

Mr. Martini is standing under the buffalo carving, which is my favorite of all the carvings on the lobby wall that depict the history of Greenwood, although Daddy says there would not have been buffalo east of the Mississippi River, which is where the Delta is. There would have been Indians, though--the Choctaw and Chickasaw including Choctaw Chief Greenwood Leflore, who was here first and signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek way before the Civil War. That's when most of the Indians moved to Oklahoma. Miss Coffee, my fourth-grade teacher, would be proud of me for remembering.

I want to focus on two passages from that paragraph.

First is the idea that Indians were "here first." It may seem innocent enough, but scholars in Native Studies see language that says Native peoples were here "first" as a way to undermine our sovereignty. If we were simply here first, followed by __ and then by __, one can say that everyone--Native peoples, too--are immigrants to this continent.

Second is "the Indians moved to Oklahoma." Written as such, it sounds like they--on their own--decided to move. Of course, they had not chosen to move. They were forcibly removed. Although Miss Coffee told Sunny about the Dancing Rabbit Treaty, I wonder if her bias in favor of White landowners and against Choctaws is evident by Sunny's takeaway: that Indians "moved" to Oklahoma. If Wiles had, in the backstory for this part of the book, a character who is Choctaw, that character could have corrected Miss Coffee. That paragraph I quoted above could then end with Sunny saying "but Joey, who is Choctaw, told Miss Coffee that his people didn't move. They were REmoved."

A plus in that paragraph is this: Sunny says "most" of the Indians moved. In that "most" she is correct. The descendants of Choctaws who refused to be removed were federally recognized as the

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians in 1945. And, Sunny's dad is wrong about buffaloes. They were, in fact, east of the Mississippi. Were they in the Delta? I don't know.

Let's return to the question posed by the Georgia State student. Let's say that the curriculum the teacher is using has the words "moved" in it and let's assume the teacher knows that the Choctaw's were forcibly removed. She could teach her students about bias right then and there, using moved/removed as an example of bias and she could provide students with information from the Choctaw Nation's website. It has a

detailed account of removal. A teacher using Wiles's book could pause the reading on page 263 to correct what Sunny learned from Miss Coffee.

The point is that teachers can address bias in materials. This is, of course, teaching children to read critically--and reading critically is a vital skill.

Thanks, student at Georgia State, for your follow up questions! I hope this is helpful.

I spent the first three days of this week at Georgia State University. I gave a lecture in their Distinguished Speaker series and several guest lectures to classes in GSU's Department of Early Childhood and Elementary Education. All meals were with students and faculty. It was a full schedule, but I enjoyed and learned from all of it and am sharing one part of it here.

Just before I got on my plane for Atlanta on Monday morning (August 31, 2015), I learned (via Facebook) that the author, Deborah Wiles, wished she'd known I was going to be there, because she wanted to meet me. I didn't know her work at that point.

Deborah was able to get an invitation to dinner on Tuesday evening. There were five of us (three professors, Deborah, and myself). I've had meals with writers before, but don't recall one like that one. I was, in short, rather stunned by most of it.

Deborah's experience of it is different from mine. Early Wednesday, she provided a recap on her Facebook page:

Last night's dinner at Niramish in Little Five Points, ATL. I got excited when I saw that Debbie Reese was speaking to students in the School of Education at Georgia State and I... um... invited myself to dinner. No I didn't. But I did squee a liitle (a lot) about the fact that she was coming. I was invited to dinner and was ecstatic about the invite, so much so that I brought everyone a book and foisted it into their hands. They were so gracious. I loved talking about children's literature and who gets to tell the story about careful, close reading, and about thoughtful critical discourse (for starters). I have long admired Debbie's work and have been getting to know my teaching friends at the College of Education & Human Development, Georgia State University this year, whom I admire more with each encounter... Thank you the invitation and generosity! Rhina Williams, Cathy Amanti, Debbie Reese, and Thomas Crisp.

I replied to her on Friday afternoon (September 4):

Deborah, you read my blog and my work, so you know I'm pretty forthcoming. I'll be that way here, too. When you brought up the who-can-write topic at dinner, there was an edge in your words as you spoke, at length, about it and criticisms of REVOLUTION. Since then, I've spent hours thinking about that dinner. I don't think we had a discussion, but I am willing to have that discussion with you. You indicate that white writers feel they can't get their books published if their books are about someone outside the writers identity. With regard to non-Native writers writing books about Native people, I don't see what you're describing. What do you think... do you want to talk more about this? On my blog, perhaps?

And she responded:

Sure, we can talk more about that. I want to make sure I am clear about what I said (or tried to say). I don't think white writers can't get their books published if they write outside their culture, not at all... these books are published all the time. I've published them. We were bouncing around quite a bit at that dinner, topic to topic. Part of what I said was that I got push-back in certain circles for writing in Ray's (black) voice in REVOLUTION, but I know that voice is authentic to 1960s Mississippi because I lived there and heard it all my life and wrote it that way. Sometimes in our (collective) zeal to "get it right" we point at a problem that isn't there. I'm happy to talk more on your blog! Thanks for thinking about it with me.

So, here's my post about that dinner. Obviously I wasn't taking notes. Deborah's comment above ("what I said (or tried to say)") demonstrates that neither of us is sure of what was said. This is my recollection and reflections on the evening.

On arriving, Deborah immediately began by talking to me about my work, saying that writers read what I say. She specifically mentioned my work on Ann Rinaldi's

My Heart is on the Ground and how that made an impact on writers.

I was, of course, glad to hear that, but then she turned the conversation to current discussions in children's literature, saying that this is a dangerous time for writers, because they are being told that they can't write outside their cultural group and that if they do write outside their culture, their books won't get published. Note that in her Facebook comment above, she said these books are getting published and uses her book as an example. I recall saying that I think these are exciting times, because we need diverse voices. It was that exchange--with her characterizing these times as dangerous and me describing them as exciting--that set the tone for the rest of the evening.

Deborah started talking about her book,

Revolution. She said that she'd shown Jackie Woodson some of the work she was doing on that book, or that she'd talked with her about the African American character, Ray, in

Revolution, or maybe it was that she'd talked with Jackie about white writers giving voice to black characters. Whatever it was, the outcome was that Deborah had a green light (my words, not hers) from Jackie. I don't doubt any of it, but I am uneasy with that sort of report. It implies an endorsement from someone who isn't there to confirm it. I'm very attentive to this because, knowingly or not, writers who do that are, in my view, appropriating that person in a way that I find inappropriate. If Deborah could point to a statement Jackie made about

Revolution, that would be different.

Deborah went on to to tell us that she had lived in Mississippi and that the voice she gave to Ray

is based on what she heard when she lived there. But, she said, "fervent" people didn't like what she did. Someone (me or one of the professors at the table) asked her who the "fervent" people are, and she said that she wasn't going to say if I was going to tell them.

I was taken aback by that and responded immediately with "well don't say then, because I will tell them." She went on to say that it is SLJ's Heavy Medal blog, and that Heavy Medal discussions are dangerous, that they have too much power in terms of influencing what people think.

Deborah seemed angry. She was talking at me, not with me. I don't recall saying anything at all in response to what she said about Heavy Medal and fervent people.

I share my recollection of the dinner--not to solicit sympathy from anyone or to embarrass Deborah--but to convey my frustration with the incredible resistance Deborah's words and emotion represent within the larger context of children's literature.

The who-can-write conversation is not new. In 1996, Kathryn Lasky wrote an article titled "To Stingo with Love: An Author's Perspective on Writing outside One's Culture." In it, she wrote that "self-styled militias of cultural diversity are beginning to deliver dictates and guidelines about the creation and publishing of literature for a multicultural population of readers" (p. 85 in Fox and Short's

Stories Matter: The Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature, published in 2003 by the National Council of Teachers of English).

I count myself in that "self styled militia." One need only

look at the numbers the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin puts out each year to see that we've made little progress:

CCBCs data shows some small gains here and there, but overall, things haven't changed much. One reason, I think, is the lack of diversity within the major publishing houses. I think there's a savior mentality in the big publishing houses and a tendency to view other as less-than. For some it is conscious; for others it is unconscious. All of it can--and should be--characterized as well-intentioned, but it is also unexamined and as such, reflects institutional racism. The history of this country is one that bestows privilege on some and not on others. That history privileges dominant voices over minority ones, from the people at the table in those publishing houses to the voices in the books they publish. That--I believe--is why there's been no progress. Part of what contributes to that lack of progress is that too many people feel sympathy for white writers rather than stepping away from the facts on who gets published.

At the end of the meal, Deborah brought out copies of her books to give to us. I got the picture book,

Freedom Summer but it felt odd accepting the gift, given the tensions of the evening. I think she was not aware of that tension. She ended the evening by praising my blog but the delivery of that praise had a distinct edge. She banged the table with her fist as she voiced that praise.

I hope that my being at that dinner with Deborah that evening and in the photograph she posted on Facebook aren't construed by anyone as an endorsement of her work. Yesterday, I went to the library to get a copy of

Revolution, because, Deborah said she is working on a book that will be set in Sacramento, and, she said, it will include the Native occupation of Alcatraz. I want to see what her writing is like so that I can be an informed reader when her third book comes out.

Before going to the library, I looked online to see if there was a trailer for it. In doing that, I found a

video of Deborah reading aloud at the National Book Award Finalists Reading event. Watching it, I was, again, stunned. She read aloud from chapter two. Before her reading, she told the audience what happened in chapter one. The white character, Sunny, is swimming in a public pool, at night. She touches something soft and warm, which turns out to be a black boy. She screams, he runs away. Then she and Gillette (another white character) take off too, but by then, the deputy is there. She tells him what happened. The last lines of that chapter are these (page 52):

There was a colored boy in our pool. A colored boy. And I touched him, my skin on his skin. I touched a colored boy. And then he ran away, like he was on fire.

As readers of AICL know, I keep children foremost in my mind when I analyze a book. In this case, how will a black child read and respond to those lines? And, what will Deborah think of my focus--right now--on that part of her book? I haven't read the whole book. No doubt, people who read AICL will be influenced by my pointing out that part of the book. Will Deborah think I am, like the people at Heavy Medal, "dangerous"?

Deborah said, above, that "

Sometimes in our (collective) zeal to "get it right" we point at a problem that isn't there." She means the people who criticized her for Ray's voice in

Revolution. The dinner and Deborah's remarks are the latest in a string of events in which people in positions of power object to "fervent" people.

Jane Resh Thomas did it in a lecture at Hamline and

Kate Gale did it in an article at Huffington Post.

I'll wind down by saying (again), that I've spent hours thinking about that dinner. It seemed--seems--important that I write about it for AICL. This essay is the outcome of those hours of thinking. I was uncomfortable then, and I'm uncomfortable now. I wanted to say more, then, but chose to be gracious, instead. I'm disappointed in my reluctance then, and now. I don't know where it emanates from. Why did I choose not to make a white writer uncomfortable? Is Deborah uncomfortable now, as she reads this? Are you (reader) uncomfortable? If so, why? Was Deborah worried about my comfort, then, or now? Does it matter?!

I can get lost in those questions, but must remember this: I do the work I do, not for a writer, but for the youth who will read the work of any given writer. For the ways it will help--or harm--a reader's self esteem or knowledge base.

The imagined audience for

Revolution isn't an African American boy or girl. It is primarily a white reader, and, while the othering of "the colored boy" in chapter two may get dealt with later in the book, all readers have to wait. Recall the words of

Anonymous, submitted to AICL as a comment about Martina Boone's

Compulsion. They have broad application:

I find the idea of a reader -- particularly a child -- having to wait to see herself humanized an inherently problematic one. Yes, it might accurately reflect the inner journey many white people take, but isn't the point that our dehumanizing views were always wrong? And therefore, why go back and re-live them? Such ruminations could definitely be appropriate in an all-white anti-racist group, in which the point is for white people to educate each other, but any child can pick up a book, and be hurt--or validated--by what's inside. Asking marginalized readers to "wait" to be validated is an example of white dominance as perpetuated by well-intentioned white folks.

It is long past time for the industry to move past concerns over what--if anything--dominant voices lose when publishers actually choose to publish and promote minority voices over dominant ones. It is long past time to move past that old debate of who-can-write. Moving past that debate means I want to see publishers actually doing what Lasky feared so that more books by minority writers are actually published.

In 1986, Walter Dean Myers

wrote that he thought we (people of color) would "revolutionize" the publishing industry. We need a revolution, today, more than ever. Some, obviously, won't join this revolution. Some will see it as discriminatory against dominant voices but I choose to see it as responsive to children and the millions of mirrors that they need so that we reach a reality where the publishing houses and the books they publish look more like society. In this revolution, where will you be?

To close, I'll do two things. First is a heartfelt thank you to Dr. Thomas Crisp at Georgia State University, for years of conversation about the state of children's literature, and, for assistance in writing and thinking through this essay. He was at that dinner in Atlanta. Second is a question for Deborah. Why did you want to meet me? Usually, when people want to meet me, there's a quality to the meeting that was missing from our dinner in Atlanta. There's usually a meaningful discussion of something I've said, or, about the issues in children's literature. That didn't happen in Atlanta. In the end, I am left wondering why you wanted to meet me.

#71 Each Little Bird That Sings by Deborah Wiles (2005)

#71 Each Little Bird That Sings by Deborah Wiles (2005)

28 points

“I come from a family with a lot of dead people.”

What a great opening line. Comfort Snowberger has attended 247 funerals, which is a lot for anybody, much less a 10-year-old. Her family runs Snowberger’s Funeral Home, where their motto is “We Live to Serve,” so Comfort and her dog, Dismay, are used to being around grieving folks. That’s not a problem. Her daddy tells her, “”It’s not how you die that makes the important impression, Comfort; it’s how you live.”

I lovedlovedloved this book. Deborah Wiles has such talent. I was in Snapfinger, Mississippi. I could see the inside of Snowberger’s Funeral Home. I was terrified on the rock with Comfort and Dismay. (And annoying Peach.) I wanted to slap Declaration’s snooty face. And I was most definitely inside Comfort’s closet with her as she sat with her mayonnaise jar of freshly-sharpened pencils. I cannot say enough great things about this one. It’s my favorite kids’ novel of all time. - Kristi Hazelrigg

When people love this book they looooooooove this book. Funny to consider that in a way it’s a sequel. Deborah Wiles wrote Love, Ruby Lavender in 2001 perhaps little dreaming that the follow-up Each Little Bird That Sings would find a devoted following. This is an entry into what we New Yorkers call (not without affection) “Southern Girl Novels”. It pretty much hits everything you expect from such a book (meaning, good food, quirky locals, etc.) while remaining touching not treacly. A delicate balance. A delicate book.

The plot summary from my own review reads, “When you grow up in a funeral home like Comfort Snowberger has, you have a healthy understanding of death. And within a single year Comfort’s Great-great-aunt Florentine and Great-uncle Edisto have joined the choir invisible. When Edisto died the funeral would have been beautiful had it not been for Comfort’s scrawny, big-eyed, unable-to-quite-grasp-the-concept-of-dying, seven-year-old cousin Peach. Peach managed to faint into a punch bowl, throw up, scream, and generally (in Comfort’s eyes) make a nuisance of himself. Now Florentine’s funeral is coming up and Peach is in Comfort’s life again. Even worse, her best friend Declaration Johnson has suddenly turned mean. Real mean. If it weren’t for her dog Dismay, Comfort might never know how to get through the next few days. But it takes losing the most important thing in her world to get our heroine to realize what it is to forgive both yourself and others around you.”

Various awards have included:

- Golden Kite Honor Book

- Bank Street Fiction Award

- E.B. White Read-Aloud Award

- Winner, California Young Reader Medal

There’s a tour journal for those of you teaching the book in some way.

Said Booklist, “Wiles succeeds wonderfully in capturing ‘the messy glory’ of grief and life.”

SLJ had some minor qualms, “Sensitive, funny, and occasionally impatient, Comfort is a wholly sympathetic protagonist who learns that emotions may not be as easy to control as she had assumed. While the book is a bit too long and some of the Southern eccentricity wears thin, this is a deeply felt novel.”

Kirkus seriously liked it, “Despite the setting and plot, the story is not morbid but

Hi Betsy,

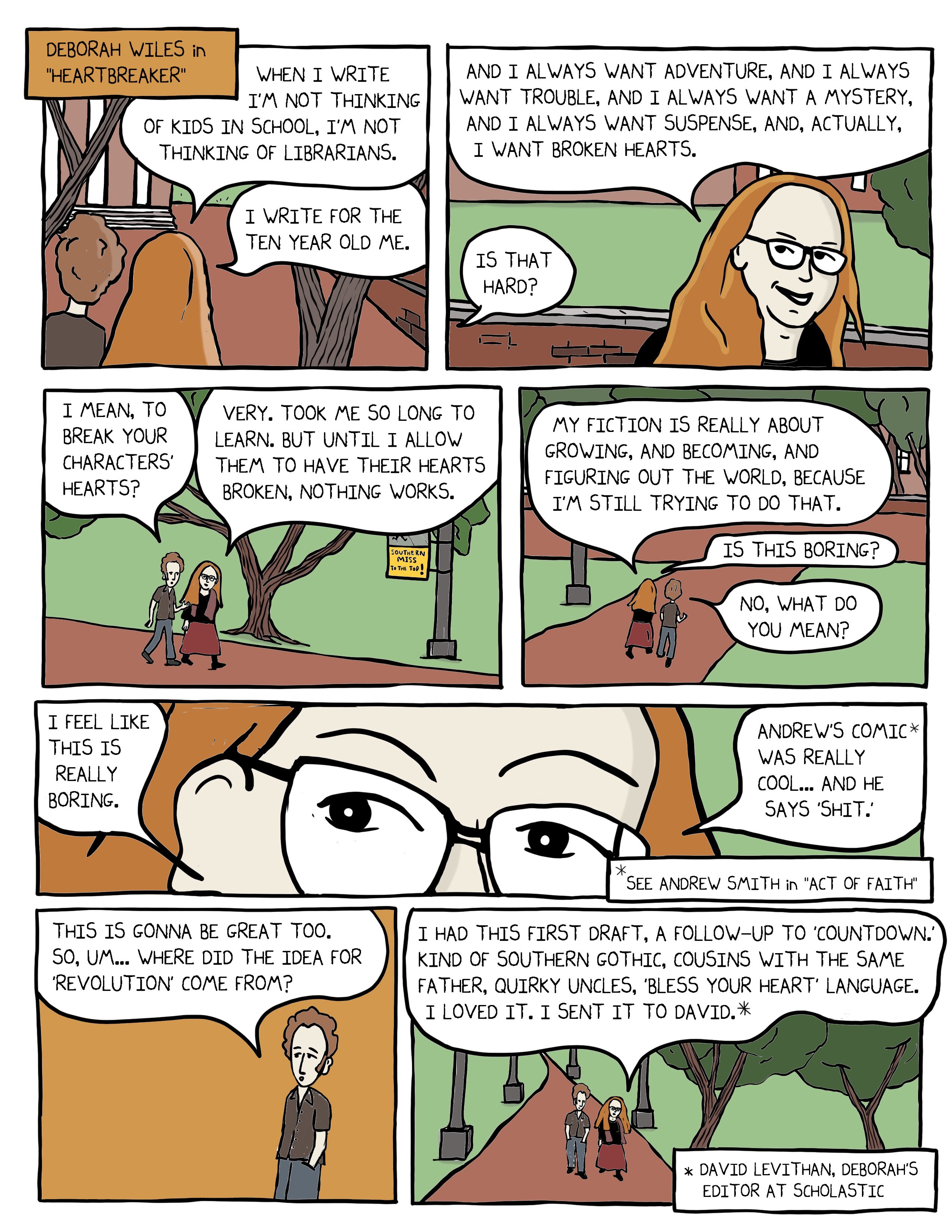

Interesting to read this comic today, after a dinner with Deborah earlier this month. I don’t, of course, know when the comic was written, but her “I write for the 10 year old me” caught my eye. In Heavy Medal’s discussions of her book, some questioned the voice/space she gave to Raymond (he’s an African American character in REVOLUTION). Fumbling around at the moment, trying to put thoughts into words, but seems that perhaps, writing for the ten year old her may be why Raymond didn’t ring true. My account of dinner is here: http://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2015/09/deborah-wiles-debbie-reese-and-choosing.html