What option can you give your students when they just get stuck?![]()

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: depression, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 63

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: inspiration, writer's notebook, genre, writing workshop, strategy charts, student engagement, ideas for the future, Add a tag

Blog: Just the Facts, Ma'am (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: genre, Add a tag

From board books through new adult, it's not just the age of the main character that differentiates the different categories of children's books from each other.

http://writeforkids.org/2015/12/understanding-childrens-book-categories/

Blog: Teach with Picture Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: literacy, free resources, genre, theme, mentor texts, teaching artifact, text evidence, Add a tag

I love using mentor texts in the classroom, and students find them incredibly useful as exemplars for their own writing. But how many times have I asked, "Do you remember when we saw examples of this technique in one of our mentor texts?" only to be met with blank stares. Or worse, a student will say, "I remember in one of our picture books the author did this thing where she said something in a way that was cool and can you help me find that book?"

So this year, in an effort to maximize our investment in mentor texts, I began to create Mentor Text Display Cards. For each exemplar text we study, whether it be a picture book, poem, article, or excerpt from a novel, I've posted a simple letter-size display card listing the book title, author, illustrator, genre, theme, notable text features, and a text excerpt (see example below). On a bookshelf adjacent to this display, I've shelved all of the mentor texts we've already read, as well as those I intend to use.

With just seven cards posted, already I've seen several benefits:

- During free reading time, students will return to these texts since they're familiar and meaningful.

- Students struggling to recall text features or literary devices will look to these cards for help.

- Students now make discoveries of their own in their independent texts, and some have even suggested picture books and excerpts for future sharing. This, in itself, is remarkably revealing, because some students are pointing out features and literary devices that haven't been formally introduced through our other texts.

- The collection of cards serves as clear evidence of our classroom goal to create a common culture of literacy.

- Printed out, these cards can be inserted in the books they reference. That way, even if you choose not to use a book in a given year, a student can still benefit from the information the card provides.

- Individual cards can be saved as pdf files, and these can be digitally stored for student access. My own teacher website has an index that would work well with this concept.

- I chose to post my cards chronologically, since students will remember a book that was read "a long time ago" (two weeks ago!) and find it easier to reference in the cards are posted by occurrence. But I can also see posting cards closer to those shelves that they might reference. So my New York's Bravest card might be posted adjacent to the Tall Tale section of my class library, and my George Bellows: Painter with a Punch card might be located near the biography section.

- As students read their own picture books (see the biography book reports here, for example), they can create their own display cards to illustrate the "take-aways" of their individual texts.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: magic, children, Books, story, Literature, fairy tale, fairy tales, truth, genre, Jack Zipes, lit, *Featured, TV & Film, oral tradition, fairy story, Arts & Humanities, literary traditions, Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, Add a tag

When some one says to you "that's just a fairy tale," it generally means that what you have just said is untrue or unreal. It is a polite but deprecating way of saying that your words form a lie or gossip. Your story is make-believe and unreliable. It has nothing to do with reality and experience. Fairy tale is thus turned into some kind of trivial story.

The post A fairy tale is more than just a fairy tale appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: genre, audience, purpose, Novel Revision, Add a tag

PB&J: Picture Books and All That Jazz: A Highlights Foundation Workshop

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info here.COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

Last year, I did a simple survey on the list and asked writers, “What is your biggest challenge for 2015?”

The answer blew me away. You want to know, “Is my picture book/novel/short story/piece of writing any good?”

This was expressed in many different ways, of course, but at the core, you want to know what makes one piece of writing good and one piece of writing bad. Is it just a matter of opinion?

When I taught freshman composition, this was a constant problem, as well. An essay turned into one teacher might receive an A, while the second teacher gave it a C; giving grades is one way to answer the good/bad question. Research showed that the solution was simple: teachers needed to meet and discuss criteria for grading. Once they’d gone through a couple essays together, they were more likely to grade consistently.

Why the problems? What does make good writing? The answer isn’t about grammar, and only incidentally about the content of the piece. Instead, you must look at the fuzzy concerns of audience, purpose, genre conventions,

AUDIENCE

Who are you writing for? Do you take the time to search images till you find a person who is your ideal audience? Writing for a middle grade student is very different than writing for a middle-aged history professor.

Again, let me demonstrate this with an example I gave to my freshman comp students. Let’s say that an 18-year-old boy has a car wreck. Now, he must tell three people about that wreck: the policeman, his mom, and his best friend. You can easily imagine each conversation. The tone—apologetic to bravado—changes with the audience. Details creep into some accounts (To Best Friend: Mary was tickling me) and are deleted from others (To Mom and Cop: I was under control of the vehicle at all times).

Which account of the car wreck would be considered “good” and which is “bad”? Is one more truthful than the other; i.e. can you apply the criteria of truthfulness to determine good/bad? You’ll agree that tone, voice, content, style and more depend on the audience.

PURPOSE

When you write a novel, do you want your reader to weep or to guffaw? The purpose of any piece of writing should—in a sane world—determine its effectiveness. Did it accomplish what you set out to accomplish?

In other words, can we use effectiveness of communication as one measure of good/bad?

GENRE CONVENTIONS

Think with me of what you expect from a mystery novel. There’s a murderer, a detective and a dead body (victim). Beyond that, though, one common convention in a mystery is to TELL the answer to the mystery. The detective arranges for all the suspects to be present at the same time, and then explains how s/he cleverly solved the problem. When confronted, the murderer tries to run away. That sort of scene would rarely happen in other genres.

Each genre has its own conventions of characters, events, plot points, settings, and so on. If you break or bend those conventions, you risk angering your readers, who will exclaim loudly, “This is a horrible mystery.”

Is it good writing or bad writing? Wrong question.

Is it a good mystery (according to the genre conventions of today)?

Is My Picture Book Manuscript Any Good?

Do you need to know if your picture book manuscript fits genre conventions? Darcy Pattison and Leslie Helakoski will be teaching PB&J: Picture Books and All that Jazz, April 23-26, 2015 at the Highlight’s Foundation, Honesdale, PA. Learn more about the workshop.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

DOES THE STORY PLEASE YOU?

Aside from issues of audience, purpose, and genre, there’s one that looms large in my mind. Does the story please you, the author? Are you happy with what you’ve done? It’s very hard to step back from your work and evaluate it. Your worries about what others think consumes you, and you can’t separate THEIR opinion from YOUR opinion.

I recently re-read my latest novel, LONGING FOR NORMAL, and at a certain point, it made me cry. A friend read it recently, too, and I asked her, “Did you cry at XXX scene?” No, she didn’t. But when I re-read that scene, I always cry. Is it a good scene? It touches me emotionally in a deep way; but it doesn’t affect my friend the same way. Is it good? Or bad?

Do you start to see that the question is the wrong one? Or that there are really two questions here:

1. Did I write the story I wanted to write?

2. How will others respond to that story?

And the terminology that you use should NOT be good/bad.

Instead, try these criteria: useful, effective, matches genre expectations, pleases me.

Then, you need to ask a final question: Do I want this to be published?

If so, you forget the good/bad question and find a publisher whose purposes, audiences and genre fits what you’ve written. And send it in. Period.

Stop those pestering questions about good/bad. Send it in. You’ll soon find out if it will fly in the marketplace you’ve chosen. If it doesn’t, go back and ask the right questions again: useful, effective, matches genre expectations, pleases me? If you’re sure you’re on target, send it out again. And again and again. Repeat until you find the right market for your work!

Blog: Pub(lishing) Crawl (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Industry Life, writing advice, genre, author brand, Add a tag

by

Erin Bowman

—

I asked for blog topic suggestions on twitter yesterday, and one of our readers posed the following (paraphrased):

There’s the idea of author brand and books readers expect from that author. But what happens if the author wants to write in a new genre?

As a YA author who debuted with a sci-fi/dystopian trilogy and is following up those three books with a historical fiction stand-alone, I find this topic incredibly fascinating. Yes, I’m changing genres, but it hasn’t worried me too much. And maybe that’s because I don’t really think my brand has changed.

As an author, the bulk of my brand is me, a human being. I’m not Nike or Starbucks*, some corporation with a logo and strict style guide. I’m Erin, who loves Harry Potter and geeks out over good typography and has an unhealthy obsession with all things Autumn. These are the things people know about me via twitter convos and blog posts, and they haven’t changed. Neither has the fact that I write YA fiction.

I’d argue that the remainder of my brand as an author is made up not by what genre I write, but by the characteristics of my novels, the type of story a reader is going to get when they pick up any of my books.

Let’s look quickly at the TAKEN trilogy and VENGEANCE ROAD. The two are very different when it comes to plot and genre classification. But if I examine the core elements of either story, there’s a lot of overlap: good vs evil, a gritty world, unexpected twists, action and adventure, a dash of mystery and a touch of romance. As such, readers who enjoyed TAKEN will most likely enjoy VENGEANCE ROAD.

I guess what I’m saying is that readers love an author less for the genre that they write, and more for the type of stories they create. If the staple elements that readers fall head-over-heels for exist in an author’s newest book, there’s a good chance readers will be happy regardless of that book’s genre or label.

Stephanie Meyer, for example, jumped from straight-up paranormal romance to light sci-fi. Many fans of TWILIGHT followed her to THE HOST and were rewarded with her staples: forbidden love, relationship drama, and a slow-burn romance. Lauren Oliver debuted with a stand-alone contemporary and then released a dystopian trilogy, but both had the beautiful prose readers expect of her, plus nuanced female friendships and well-developed themes of love/family.

Perhaps the more difficult-to-navigate transition is changing audiences—switching to MG or adult, after establishing yourself as a YA author. Naturally not all of your existing readers will follow you if you do this, simply because the new book is meant for a completely different age group. Still, Oliver has found success writing for a variety of audiences, as have others.

At the end of the day, the advice we hear over and over is to write the story that excites us, the book we’d want to read. I still think this is some of the best advice around. Let your publisher worry about how to entice your existing fanbase to try your next-book-in-a-new-genre. You just worry about writing an awesome book. Be aware of what elements from New Book will also appeal to fans of Old Book, if only so you can better promote it to your existing readers when the time comes, but write what makes you happy. Life is too short (and the publishing industry too uncertain) to write only within one genre if you’re anxious to try others.

Remember: Labels are a result of bookstore and library shelving. They are a necessary evil of the industry. But readers just want good stories. So go write good stories, genre be damned.

* Nike and Starbucks are the brands, sneakers and coffee are the products, respectively. The same is true for authors. The brand is the person, the product is the books.

—

Erin Bowman is a YA writer, letterpress lover, and Harry Potter enthusiast living in New Hampshire. Her TAKEN trilogy is available from HarperTeen (FORGED out 4/14/15), and VENGEANCE ROAD publishes with HMH in fall 2015. You can visit Erin’s blog (updated occasionally) or find her on twitter (updated obsessively).

Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: creative risk, writing life, genre, market, audience, format, Add a tag

|

|

|

I’ve been writing for years. (Let’s not discuss how many exactly!) It’s easy to fall into habits and to think about stories in certain ways. The best creative people, though, insist that they are constantly learning and to do that, they try something different. They take risks.

Let me suggest some risks you might want to take:

Try a different genre. If you’ve only written nonfiction, try a novel. Love writing picturebooks? Try a webpost. Good writing is good writing is good writing. But platforms DO make a difference in length, diction (your choice of vocabulary to include/exclude), voice and more. Why not try writing a sonnet?

Try for a different audience. Stretch your genre tastes and try a different one. Write a romance for YAs. Or a mystery for first graders. Are all of your protagonists female? Then try writing from a male’s POV and try to capture a male audience.

Try a different process or word processing program. I took a class on Scrivener this spring and am continuing to explore what this amazing program can and can’t do. I’m also learning Dragon Dictate to lessen the ergonomic strain on my hands. I know that these programs have potential to change not just my writing process, but also the output. I’m just not sure HOW they will affect it. It’s a risk.

Market to different places. While we often separate the writing from the marketing–especially when we think about the creative process–I think you can still take creative risks with marketing. For example, identify a market FIRST, and write specifically for that market. In this case, you are letting the market sculpt your creative output. If you write a short story for Highlights Magazine for Kids, it’s got to be 600 words or less. If you write an op-ed piece for the Huffington Post, everything is different in your creative output. If you decide to self-publish, you may find yourself suddenly taking the question of commercial viability much more seriously.

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: genre, blog series, Independent Writing Blog Series, Add a tag

The last quarter of the school year brings gifts all its own – it’s a time to celebrate all the investment that has been made during the first three quarters: our… Continue reading ![]()

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Humanities, *Featured, form, Classics & Archaeology, classical literature, William Allan, ‘imitation’, Poetry, Literature, classics, genre, VSI, Very Short Introductions, tragedy, Add a tag

By William Allan

One of the most striking aspects of classical literature is its highly developed sense of genre. Of course, a literary work’s genre remains an important factor today. We too distinguish broad categories of poetry, prose, and drama, but also sub-genres (especially within the novel, now the most popular literary form) such as crime, romantic or historical fiction. We do the same in other creative media, such as film, with thrillers, horrors, westerns, and so on. But classical authors were arguably even more aware than writers of genre fiction are today what forms and conventions applied to the genre they were writing in. All ancient literary texts are written in a particular genre, such as epic, tragedy, or pastoral. This doesn’t mean that one genre can’t interact with another, and they often do, as in ‘tragic history’, that is, history written in the style of tragedy, as when Thucydides presents the Athenian empire’s disastrous attempt to conquer Sicily as a typically tragic story of hybris and ruin. Some modern theorists would argue that every text belongs to a genre and that it is impossible not to write in one: thus even those nifty writers who try to break free of convention and write the wackiest stuff are still caught up in ‘experimental’ literature. The invention of the major literary genres and their norms is the most significant effect of classical literature’s influence.

But what is a genre? The first thing to observe is that a genre is not a rigid mould which works must fit into, but a group of texts that share certain similarities – whether of form, performance context, or subject matter. For example, all the texts that make up the ancient genre of tragedy share certain ‘family resemblances’ (they are theatrical texts written in a particular poetic language, they reflect on human suffering, they show gods interacting with humans, and so on) that allow us to perceive them as a recognizable group. But although certain ‘core’ features characterize any given genre, the boundaries of each genre are fluid and are often breached for literary effect.

As can still be seen in modern literature and film, a genre comes with certain in-built codes, values, and expectations. It creates its own world, helping the author to communicate with the audience, as she deploys or disrupts generic expectations and so creates a variety of effects. Genres appeal to writers because they give a structure and something to build on, while they offer audiences the pleasure of the familiar and ingenious diversion from it. The best writers take what they need from the traditional form and then innovate, leaving their own imprint on the genre and changing it for future writers and audiences. In other words, genre is a source of dynamism and creativity, not a straitjacket, unless the writer is rubbish, i.e. unimaginative and unoriginal.

All ancient writers had an idea of who the top figures in their chosen genre were (Homer and Virgil in epic; Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides in tragedy, and so on), and their aim was to rival and outdo their predecessors. The key ancient terms for this process of interaction with the literary past are imitatio (‘imitation’) and aemulatio (‘competition’). ‘Imitation’ doesn’t mean slavish copying, but creative adaptation of the tradition; creative writing today still involves the reworking of previous literature, since writers are usually enthusiastic readers too. Of course, competing with the great writers of the past is a risky business – as Horace puts it, ‘Whoever strives to rival Pindar exposes himself to a flight as risky as that of Icarus’ (Odes 4.2.1-4, paraphrased) – but what characterizes the best writers of antiquity is their response to the great works of the past in the light of the present.

The central role of ‘imitation’ in classical literature also helps explain why ancient authors allude so frequently to other texts. With ‘the death of the author’ in postmodern thought, the wider term ‘intertextuality’ is now trendier than ‘allusion’, referring to the interconnections between texts, deliberate or not. Be that as it may, deliberate allusion is an important part of the writer’s meaning in classical literature, and the ideal reader of Virgil’s Aeneid, for example, an epic that draws on a variety of other genres (including tragedy, history, and love poetry, among others), will be able to appreciate how Virgil alludes to, and reworks, earlier texts in order to create his own meaning.

Mention of epic reminds us that classical literature is characterized by a hierarchy of genres, ranging from ‘high’ forms such as epic, tragedy, and history at one end through to ‘low’ forms such as comedy, satire, mime, and epigram at the other. ‘High’ and ‘low’ relate to how serious the subject matter is, how lofty the language, how dignified the tone, and so on. Many of the genres lower down on the hierarchy define themselves polemically in opposition to a higher form: thus writers of comedy, for example, poke fun at tragedy, presenting it as unrealistic and bombastic, in order to assert the value of their own work, while satire mocks the claims of epic and philosophy (among other genres) to offer meaningful guides to life. Finally, it is striking that some genres endure longer than others: Roman love elegy flourished for only half a century, while epic was always there, and always changing.

In conclusion, then, we can understand an ancient literary text properly only if we take into account where it comes in the evolution of its genre, and how it engages with and transforms the conventions it inherits. The same is true of our literature too, of course, not least because classical works, with their highly developed sense of genre, form the foundation of the Western literary tradition.

William Allan is McConnell Laing Fellow and Tutor in Classics at University College, Oxford. His publications include Classical Literature: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2014).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday, subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS, and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy. Mosaic, Roman artwork, 2nd century CE. From the Baths of Decius on the Aventine Hill, Rome. Capitoline Museums. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Why literary genres matter appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, writers, genre, Add a tag

In my sixth grade class, we cycle through a set of genres every Writing Workshop year: personal narrative, memoir, feature article, poetry, profiles, and persuasive letters and research based essays. Taken together, these… Continue reading ![]()

Blog: Anwers from digital publisher (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Answers, Personal Experience, Writing book, Creating character, Marketing, Publisher, Reading, Book, Authors, Publishing, Articles, WRITING, Writers, Australia, Readers, Published, Genre, Add a tag

The myth that publishers have stacks of manuscripts and that writers have to line up in a long queue was deflated by Jennifer Bacia during her talk at the Gold Coast Writers Association meeting . ‘Actually, that is not the case’ she stated. According to Jennifer, publishers are always looking for something that will make […]

Add a CommentBlog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

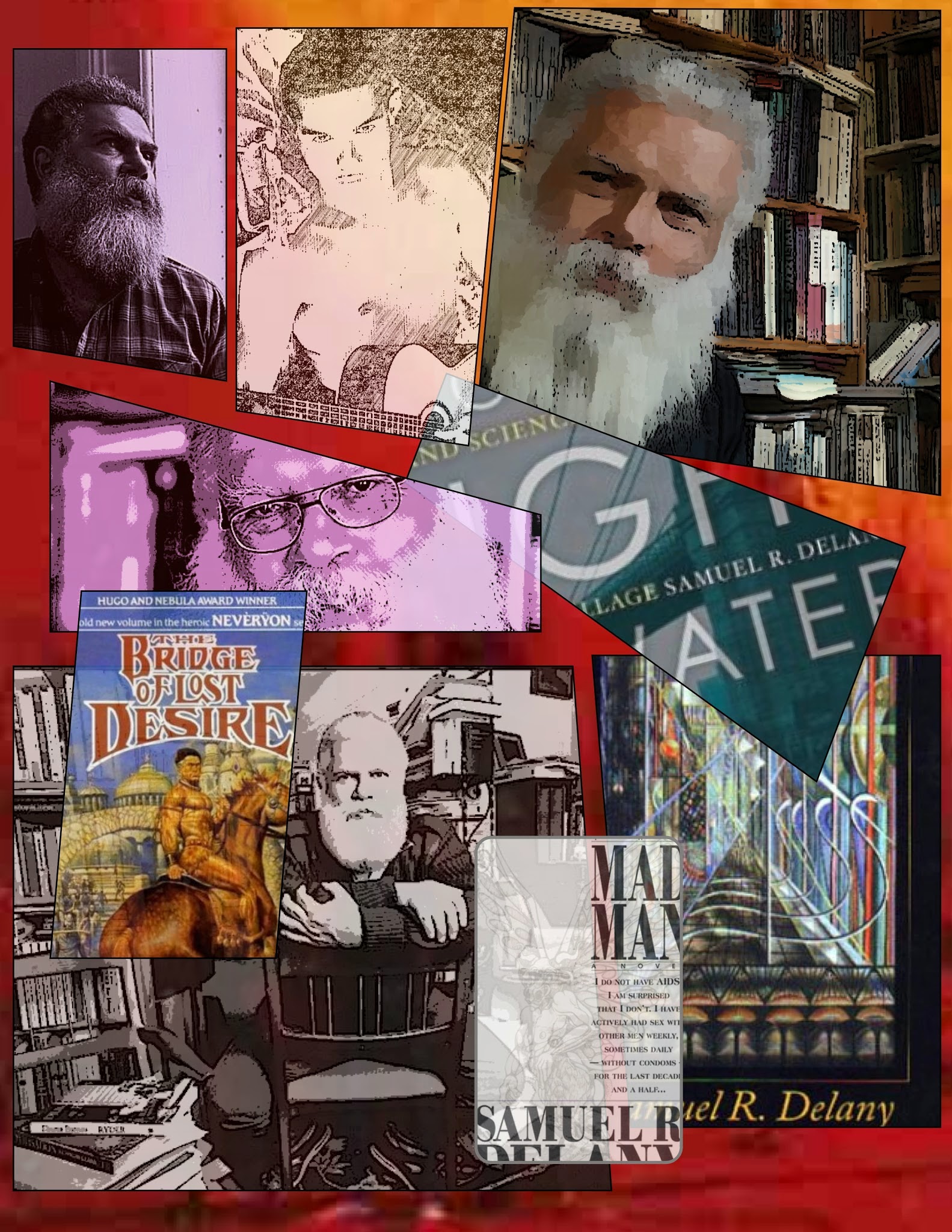

JacketFlap tags: pornography, Geoffrey H. Goodwin, Eric Schaller, Craig Laurance Gidney, Ethan Robinson, Keguro Macharia, Lavelle Porter, Njihia Mbitiru, books, science fiction, genre, Delany, Nick Mamatas, Add a tag

So here we are. I put out the call to a wide variety of folks, and this is the group that responded. We used a Google Doc, and the discussion grew rhizomatically more than linearly, so you'll see that we sometimes refer to things said later in the roundtable. (This makes for a richer discussion, I think, but it may be a little jarring if you expect a linear conversation.)

PARTICIPANTS

Matthew Cheney has published fiction and nonfiction in a wide variety of venues, including One Story, Locus, Weird Tales, Rain Taxi, and elsewhere. He wrote the introductions to Wesleyan University Press’s editions of Samuel R. Delany’s The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, Starboard Wine, and The American Shore (forthcoming). Currently, he is a student in the Ph.D. in Literature program at the University of New Hampshire.

Craig Laurance Gidney is the author of Sea, Swallow Me & Other Stories and the YA novel Bereft.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin is a journalist, author, and rogue academic with a Bachelor’s in Literary Theory (Syracuse University) and an MFA in Creative Writing (Naropa University). Geoffrey writes fiction; has taught composition and creative writing in a wide range of settings; has interviewed speculative writers and artists for Bookslut, Tor.com, Sirenia Digest, The Mumpsimus, and during Ann Vandermeer’s helming of Weird Tales; and has worked in seven different stores that have sold comic books.

Keguro Macharia is a recovering academic, a lazy blogger, and an itinerant tweeter. Sometimes, he writes things on gukira.wordpress.com or tweets as @Keguro_

Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Love is the Law and The Last Weekend. His short fiction has appeared everywhere from Asimov’s Science Fiction to The Mammoth Book of Threesomes and Moresomes.

Njihia Mbitiru is a screenwriter. He lives in Nairobi.

Lavelle Porter is an adjunct professor of English at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) and a Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. His dissertation The Over-Education of the Negro: Academic Novels, Higher Education and the Black Intellectual will be completed this spring. Finally. He’s on Twitter @alavelleporter.

Ethan Robinson blogs, mostly about science fiction, at maroonedoffvesta.blogspot.com, a position he will no doubt shortly be parlaying into literary fame.

Eric Schaller is a biologist, writer, and artist, living in New Hampshire and co-editor of The Revelator.

THE ROUNDTABLE

Matthew Cheney

How has Delany influenced your own work or views on writing and literature?

|

| detail of the cover of Dhalgren (Bantam, 1975) |

Geoffrey H. Goodwin:

If one looks at his criticism, fiction, memoirs, and cultural relevance--not to mention everything else he’s accomplished--he’s incomparable. Sure, I remember how he offered the particle theory, where we read and read and then emit a particle on our own when we write, inspired by how we bombarded ourselves; or how he made sure to place the Marquis de Sade’s books within his young daughter’s reach because he wanted her to make her own choices about literature, and there were lessons and exercises in the workshop that were profound--but I also think of Chip as someone with whom I got to trade stories about Allen Ginsberg for stories about Philip K. Dick and Clive Barker. He’s a constellation in a tiny pantheon of living geniuses.

Nick Mamatas

I guess I appreciate Delany more as a reader than anything else. He doesn’t influence my writing, or my views. There are aspects of agreements, but I haven’t changed my mind about anything to coincide with Delany’s views. I always assign his book on writing—I’ve probably sold an extra fifty copies so far—not because I agree with everything in it, but because everything in it is worth tangling with.

Ethan Robinson

Keguro Macharia

I’ll lift Matt’s second prompt below--on beginnings--and track back to the Locus conversation, which started with “beginnings”: when did you first encounter Delany? Which is also a question about SF as a genre that (to my mind) obsesses about beginnings and endings (ecocides, genocides, monsters, hybrids, extinguishment, survival). Which is also to borrow from Lavelle about AIDS and Delany and, more broadly, the forms of extinguishment and disposability his work speaks to and, in doing so, enables us to speak about--this is the importance of Hogg as an early work. I first encountered Delany in the Patrick Merla anthology (Boys Like Us) that Lavelle mentions below. I don’t remember reading him then and, in fact, I suspect that I did not know how to read him at the time--I wanted a simple(r) narrative than he was willing to offer, a cleaner story that stayed “inside the lines,” affirmed identity, made the pleasures of identification simple, the practices of belonging uncomplicated. (Although Matt wants us to be polite, I’ll add that I read much of this impulse in the Locus discussion.)

I re-encountered Delany through Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, just before I joined grad school. At the time, I was interested in formal innovation, and Times Square modeled the kind of writing and thinking I found necessary as a form of world building. I came to the novels later--Stars in My Pocket, Hogg, Mad Man, the Nevèrÿon series, at much the same time as I was reading Delany’s many essay collections. Delany helped me see form--why form matters, how form matters, to whom form matters, why formalism matters--as a project of world-building, world-remaking, inextricable from embodiment, desire, fantasy, and speculation.

Njihia Mbitiru

I have absolutely no idea, yet, about his influence on me. Others have spoken with great perspicacity--as well as humor (Brett Cox in the Locus roundtable being one)--about Delany’s influence. I suspect I’m still working through mine and therefore limited in what I can say about it. The first bit of Delany’s writing I encountered was The Towers of Toron, the first in the Fall of the Towers Trilogy. I was twenty-one, if I recall correctly. That was twelve years ago now. I’ve become an avid re-reader of his work, which has made me a re-reader of many other writers I onced-over. And because of this I would very much like to hazard that I am now a better reader, but this also remains to be seen: the simple fact is that proof of such is in writing, whose excellence, much as we strive toward our own finally idiosyncratic sense of it, is also a public affair.

Matt: just to touch on what you’ve said about the narrative of certain of his writings--the later ones, beginning with Dhalgren (written in his late 20s and early 30s, you’ll recall! so that it’s hard to think of this as ‘late Delany’): I also resist and reject this narrative ( I’m not quite at resentment, but give me time). I find it completely non-sensical. Better and more honest to say, as a reader, that the game he’s hunting as a novelist in Dhalgren, Triton, the Neveryon series up into his present work doesn’t hold your interest. It’s a long way away from that to ‘difficult’. Only a very narrow reading of SF writing would support an assessment of Delany as ‘difficult’, if we’re talking about prose style (though I suspect that’s not what is meant, which begs the question: what do people mean exactly when they use the term ‘difficult’?). There’s so much at a SF readers’ disposal in terms of range and sophistication, or if you like, the absence of it, as there is in any other genre. I enjoy and appreciate Delany’s writing in no small part because it calls attention to precisely this.

Eric Schaller

Delany’s writings have influenced me more in my approach to life and thought than in writing itself. Some may dislike John Gardner’s concept and application of ‘moral fiction’ to literature, but I have always found Delany’s work moral in its suggestion of how to live a good life. In this respect, as a philosophy, I could abbreviate it as ‘compassionate individualism’: the importance of discovering and following your own path, the diversity of such paths within a population, and how to maintain your personal dignity without selfishly depriving others of theirs. The dedication in Heavenly Breakfast ("This book is dedicated to everyone who ever did anything no matter how sane or crazy whether it worked or not to give themselves a better life"), when I read it in college brought tears to my eyes, and still does.

Through Delany’s writings, I like to think that I became more intentionally aware. My discovery that Delany was gay—not necessarily obvious from his earlier novels, which featured plenty of male-female couples, or from his earlier biographical information which sometimes mentioned a marriage—more specifically the worlds revealed in his non-fictional/autobiographical works such as The Motion of Light in Water, the contemporary sections from “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” and, more recently, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue personified concerns that I would never experience directly. I donate to GMHC because of these works.

There seems to be a narrative among science fiction fans, and particularly SF fans of a certain age, that there is The Good Delany of the pre-Dhalgren books, Hugo and Nebula Awards, etc. ... and then there is The Problematic Delany of Dhalgren and later. It’s a narrative of loss and disappointment, frequently accompanied by the question, “What happened?!” Because I was born in the year Dhalgren was, at least officially, published (it bears a January 1975 publication date, though it actually hit shelves a little earlier), and didn’t start reading Delany until either late 1987 or sometime in 1988, when the last Nevèrÿon book, The Bridge of Lost Desire (Return to Nevèrÿon) was published, my awareness of his career has always included what older, more traditional SF readers considered the “difficult” writings. It’s probably not surprising that I resist, reject, and resent this narrative.

The book I’ve spent the most time with recently, because I’m working on a conference paper about it, is Dark Reflections, which is really beautiful and much more complexly structured than it seems at first, and which should be accessible to just about any audience, since it’s not at all pornographic and the complexity of the structure is subtle, making a basic reading relatively easy. Also, the book’s a great companion to About Writing, which it echoes often. (There’s some good discussion of the “accessibility” of Dark Reflections, particularly for heterosexual men, in Delany’s 2007 interview with Carl Freedman in Conversations with Samuel R. Delany.) But for various reasons, some having to do with events in the publishing industry, Dark Reflections does not seem to have been widely read, and is currently only in print as an e-book. It deserves a wide audience, though.

So my questions for the roundtable are: What other, more useful, stories of Delany’s career could we tell? Is the Good Delany/Problematic Delany narrative useful in some way that I’m missing, some way that I can’t see because it just makes me so angry?

Ethan Robinson

Craig Laurance Gidney

My first introduction to Delany was, interestingly enough, Dhalgren. My older brother had a copy of the book when it first came out in the ‘70s and I appropriated it. I read the book in bits and pieces during my teenaged years, and it formed my taste for esoteric and trippy SF. When people spoke about how difficult the book was, I had a hard time understanding them, maybe because I absorbed the idea of the non-linear and counter-factual texts so young. Everything of his I read is through the locus of Dhalgren. The earlier stuff is great to me because I can see the progression of themes that were refined in his later work.

Eric Schaller

I don’t think I read a novel of Delany’s until the summer after graduating high school. I was working in New York City at Sloan Kettering and the novel was Dhalgren. There had been the joke published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction about the three things that mankind would never reach (“The core of the sun, the speed of light, and page 30 of Dhalgren”), but this if anything incited my interest in the novel. I was of the right age and in the right place to have the novel assume a central station in my life. But it is also one of those novels that I have returned to and re-read over the years, each time taking something new away from it. For instance, Delany having written that The Fall of the Towers was inspired by a painting of that title which did not show towers but rather reactions to their fall, I noticed a similar approach was often used in Dhalgren: the reactions of characters described before you understood to what they were reacting.

As an undergraduate at Michigan State, I sought out every Delany book I could find. And to my mind then, and still, there were differences in the approach to writing found in his early works to what I found in Dhalgren and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. The closest I can come to that difference is to say that in the earlier work Delany seemed to be thinking at a sentence to sentence level. With the later work, it seemed that he inhabited whole paragraphs at once; an individual sentence might not seem that powerful or poetic alone, but within the context of the paragraph it sang.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin

Nick Mamatas

I actually prefer his porn to his SF for the most part. It’s difficult to write transgressive, dirty, occasionally simply wrong stuff with such sympathy and warmth, but Delany manages it. He is an utterly unique writer in th

Blog: The Canticle (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Advice, genre, Michael Young, writing videos, Add a tag

Know Your Genre Genre = the category your writing falls into. Bookstores, reviewers and sellers separate books by genre to help readers. A genre tells you what kind of conflict you will have and how it will likely be resolved.

Blog: Miss Marple's Musings (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: expats in New York, FREAKBOY, Kristin Elizabeth Clark, Lesléa Newman, LGBTQ authors, OCTOBER MOURNING, YA, YOUNG ADULT, writers, readers, Book recommendation, genre, contemporary fiction, novels in verse, SMOKE, Ellen Hopkins, Patricia McCormick, Sold, MFA in Creative Writing, Writerly Musings, Add a tag

Mondays on this blog will be given over to musings on being: a writer (for children), a voracious reader, an MFA student, an expat in New York, a nature advocate, part of the LGBTQ community, a lifelong wanderer, an obsessive observer of human nature, and one who jives to the java bean and the fermentation-flirtation of the Cabernet Sauvignon grape!

While I shall most definitely be writing a post on, ‘Why One Should Read Outside One’s Genre,’ today I espouse the importance as writers of reading the themes, content, forms and genre in which we have rooted our own manuscript. You need to know how your book compares with the competition, and how it is different. Reading your genre is about staying current as an author, just as a teacher or doctor might. Agents and publishers will expect this of you, and you should certainly know on which shelf in a (Indie) bookstore a reader should be able to find your book!

I like to not only read in my genre, but also books that have focused on some of the big themes and subject matter in my story; maybe betrayal, or teenage pregnancy, maybe set in other cultures, or in slang…. You might read to be inspired by form and style. Maybe you are seeking to write in a more literary style, then you could perhaps read Laurie Halse Anderson’s WINTER GIRLS. Since meeting and reading most of the works of author, Ellen Hopkins, I have been fascinated by the form of novels written in verse, and have been reading broadly in this form. I am thrilled that we have on the faculty of the Stony Brook MFA program, Patty McCormick, whose novel in verse, SOLD, has so much of what I want to explore in my own writing.

In which genre are you writing? And/or what theme(s) are you exploring, and what recommendation do you, therefore, have for us? Let me kick off, and let me say that while my novel is at present in prose, I am drawn to a more poetic vehicle for the story.

Genre: Contemporary YA fiction (edgy) Form: narrative prose Themes: Estrangement, abusive parental relationships and/or LGBTQ characters and bullying

My recommendations:

SMOKE by NYT best selling author, Ellen Hopkins and published by Simon and Schuster. I was lucky to read an ARC of this novel in verse, which is released tomorrow, September, 10th 2013. I loved BURN and was not disappointed with this sequel. SMOKE addresses big themes – courage and survival, abuse, hypocrisy and silence in religious communities (LDS), gay bullying, neglect, love… the writing is quick and sparse and visually meaningful. All the characters are 3+ dimensional. If you have never read a novel in verse, I highly recommend any of Hopkin’s novels. SMOKE is also included in this recent list of Top Ten YA Releases in Sept 2013.

SMOKE by NYT best selling author, Ellen Hopkins and published by Simon and Schuster. I was lucky to read an ARC of this novel in verse, which is released tomorrow, September, 10th 2013. I loved BURN and was not disappointed with this sequel. SMOKE addresses big themes – courage and survival, abuse, hypocrisy and silence in religious communities (LDS), gay bullying, neglect, love… the writing is quick and sparse and visually meaningful. All the characters are 3+ dimensional. If you have never read a novel in verse, I highly recommend any of Hopkin’s novels. SMOKE is also included in this recent list of Top Ten YA Releases in Sept 2013.

Okay, I have not yet read FREAKBOY, a YA novel in verse by Kristin Elizabeth Clark, which is going to be published on October 22nd, 2013, by Farrar, Strauss and Geroux, but I have discussed the book with the author and am a huge fan of her writing and very happy to see a book embracing these themes. I am convinced this will be a book with significant ripples in the YA book community. Just this week it received a starred review -“*”This gutsy, tripartite poem explores a wider variety of identities—cis-, trans-, genderqueer—than a simple transgender storyline, making it stand out.“ — Kirkus Review, starred review.

which is going to be published on October 22nd, 2013, by Farrar, Strauss and Geroux, but I have discussed the book with the author and am a huge fan of her writing and very happy to see a book embracing these themes. I am convinced this will be a book with significant ripples in the YA book community. Just this week it received a starred review -“*”This gutsy, tripartite poem explores a wider variety of identities—cis-, trans-, genderqueer—than a simple transgender storyline, making it stand out.“ — Kirkus Review, starred review.

You can buy it now, here.

OCTOBER MOURNING by Lesléa Newman, published by Candlewick, September 25th, 2012. “A masterful poetic exploration of the impact of Matthew Shepard’s murder on the world.”

OCTOBER MOURNING by Lesléa Newman, published by Candlewick, September 25th, 2012. “A masterful poetic exploration of the impact of Matthew Shepard’s murder on the world.”

On the night of October 6, 1998, a gay twenty-one-year-old college student named Matthew Shepard was lured from a Wyoming gay bar by two young men pretending to be gay. Matthew was savagely beaten, tied to a fence, and left to die. October Mourning, is the author’s deep personal response to the events of that tragic day. It is a novel in verse, but quite different from the previous two as Newman creates fictitious monologues from various points of view, including the fence Matthew was tied to and the girlfriends of the murderers. This is a heartbreaking series of sixty-eight poems in several different poetic forms offering the reader an enduring tribute to Matthew Shepard’s life.

Your turn! Please add your recommendations in the comments below.

Blog: From the land of Empyrean (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: movie, crime, genre, local author, trilogy, cosplay, psychological thriller, Keith Rommel, authors in the park, costume contest, booktoberfest, Add a tag

Keith will be making his first appearance at Authors in the Park's Booktoberfest on October 5th (Details HERE). In the meantime, he would like to discuss the challenges of genre hopping and plotting out a good story.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, mystery, plot, craft, genre, Pure, Julianna Baggott, Gillian Flynn, Dark Places, dystopia, reading, Add a tag

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, writing, characters, plot, communication, craft, dialogue, genre, argument, Add a tag

Let’s take a stroll back to beginning composition class to figure out how to illustrate a convincing change in character motivation.

In once scene Dick makes a point. In another scene Ted makes his counter point. Each encounter they have is an attempt to sway or force each other to adopt the opposite way of thinking. A different point is driven home each time.

Ted's scenes illustrate why he wants humankind destroyed. Ted may think Dick is a hopeless dreamer. Dick may drive home a few points that make Ted reconsider.

Dick's scenes address the reasons humanity should be saved. A few scenes could show him questioning his stance. Yet, it is Dick’s belief in the innate goodness of mankind that eventually gives him the tools or the access to stop Ted’s nefarious plan.

There will be friends that fight alongside Dick to save mankind. There may be a secondary character that is on the fence. Perhaps he or she encounters Sally and wonders if Dick is fatally naive. Jane could have a perilous dilemma of her own and her self-sacrifice illustrates Dick’s point that humanity is worth saving.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: interiority, conflict, fiction, writing, genre, anxiety, anticipation, motive, Add a tag

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: career, voice, genre, novel revision, build a career, Add a tag

|

Reading would be boring, except for the person behind the writing. YOU make it interesting. Your voice.

Even the federal government recognizes the importance of YOU: ideas can’t be copyrighted, rather, the particular expression of an idea. What you copyright is your voice. You.

This means several things:

Voice. As you write, be aware of your particular ways of thinking, of what you notice, of how you express what you notice. Try to foster those interests and expressions. Of course, this isn’t a call to be sloppy in grammar or word usage or sentence structure. Just as a jazz player plays a riff on a song, so you must experiment in your writing, while still making sure the song is recognizable.

Match voice to genre. Your voice–who you are–will also determine the types of writing at which you can excel. Nonfiction or fiction, horror or romance–you need to find a place where your voice fits naturally and allows you to exploit your voice. Experiment with genre, style, length, and venue (online v. print, for example), to find the “highest and best use” of your strengths.

Editors. We all need feedback and early editors. Be careful, though, of line editors, those people who think something must be said their way. Unless they are extremely skilled, line editors mess with voice. And you must not allow that.

Stick with a genre, character, series. If and when you find that sweet spot, stick with it. Careers are built on returning readers, who become fans, who faithfully buy everything you write and furthermore, they tell friends to buy them and they give your books as gifts. Early in your career, don’t worry about bouncing around and writing everything you might want to write. If you are lucky enough to find success in one area, stay there long enough to build a readership that you will take with you to the next step.

You. Your lens, the way you see the world, the way you express what you see–that is what keeps reading from being boring. Let me see the world the way YOU see it. And I’ll keep reading you.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: historical fiction, fantasy, NaNoWriMo, genre, WiFYR, Game of Thrones, story mapping, Add a tag

Blog: Jennifer Represents... (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: queries, genre, agent-hunting, Add a tag

A couple of years ago I wrote The Big Ol' Genre Glossary. This blog post was intended to be "the last word" on the subject of genre identification, etc. Ha ha, is all I have to say to that.

As you might know if you ever go on internet writing fora, there are some genres and sub-genres that are just fuzzy, and there is a lot of overlap. Five different people might have five very different ideas about what constitutes "paranormal" versus "supernatural" versus "urban fantasy" versus WHATEVER. People can get very anxious about how to categorize their own work. I've had writers say to me, in tones of deadly seriousness, that they know agents will look for any reason to reject, and if they get the sub-genre of their own work "wrong," they will never be taken seriously and agents will hate them. That getting this bit of information "wrong" will be cause for an auto-reject.

Yes! Those terrible, dragon-like AGENTS. Always keen for any small reason to run writers through with a pike and roast them alive, the better for the feasting! Oh you didn't know we get younger every time a writer screams? Yes! Your agony is our elixir! Our blood is thrumming with your pain!

Oh, the guild tells me I was not supposed to say that last part aloud. Please strike it from the record. Also disregard the cackling. Now. In all seriousness.

For the most part... Agents are just people. People who love books, and who want to help facilitate the making of books. People whose job it is to advocate for authors. (That FOR is quite important!). We work with a lot of authors. We LOVE authors. We recognize that authors can sometimes be neurotic. We are not trying to drive authors crazy (or crazier, anyway).

This drama that the internet has cooked up about agents declining you because there was a typo in your query, or because you formatted an email query letter as a business letter complete with home address (or failed to do so), or double-spaced when you meant to single-space... or because you said "dark fantasy" when you meant "urban fantasy" or "paranormal" when you meant "supernatural"? Is just not true.

* First of all, as I mentioned, there is a lot of overlap, and different people have different definitions. If an agent was to decline your work based on that alone? They are not somebody you'd want to work with.

* Tying yourself in knots because of this kind of minutia may be keeping you from looking at the bigger picture, and at things that actually WILL cause agents to accept or decline your work. Things like having a killer pitch and tight, great, polished writing in the actual ms. This is truly what the agent cares about most.

* Some of the most interesting books defy easy categorization. If you have a book that is gorgeously written but also highly commercial, that is a GOOD THING. If as a genre it is something that lies on the crossroads between mystery, romance and fantasy (or whatever) -- that too is probably a GOOD thing, not a bad thing.

* If you have a magical story and you just call it "fantasy" I won't even blink an eye. The default "big category" of Fiction, SF/F, Mystery or YA is actually sufficient information. If you want to get more specific, that's fine. But if you go nuts with it and decide to make up a genre like "high-urban-splatter-steam-rotica"...well if it seems like you're joking, I'll chuckle. If it seems like you are being serious, I'll roll my eyes. But if the book sounds interesting, even that bit of silliness wouldn't stop me from continuing.

* IN fact I'll go further and contend that "overcategorizing" is self-limiting. If you've written what you consider to be "high-urban-splatter-steam-rotica"... you'll never find an agent who reps that, no matter how much research you do. If you consider your work a "Steampunk inspired paranormal-mystery" you might find a couple of agents who rep all of those categories. But if you just call it FANTASY, wow, suddenly you have a ton of potential people to query, and you can pick and choose who seems like might be the best fit from this larger pool.

* So sure, absolutely, give categorizing your best shot. But if you find yourself freaking out over which sub- or sub-sub-genre your work falls into, understand that this is of little concern to agents at the query stage. They care that the story sounds cool and the writing is excellent. And that is where you should be putting your energy.

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: fiction, nonfiction, Writing, Quotes, genre, Add a tag

In the author's note to his new collection of essays, Magic Hours, Tom Bissell calls himself "an accidental nonfiction writer", and then says:

When I first started writing for magazines, I imagined that I would use nonfiction writing as a way to fund my fiction writing. This did not go exactly as planned. Insofar as I am known as anything today, it is as a nonfiction writer. Earlier in my career, I was neurotic enough to let this bother me. When I started out as a writer, I regarded fiction — novels, especially — as the supreme achievement of the human imagination. While I still hold fiction in very high regard, and continue to write it, I no longer believe in genre chauvinism. Life is difficult enough.

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Africa, short stories, genre, pulps, Caine Prize, Add a tag

This is my fourth post for the great 2012 Caine Prize blogathon. (See my first post for some details.)

With 2 stories remaining for our Caine Prize Blogathon of Wonder, I fell behind.

Thus, this post will be about the last two stories, "La Salle de Départ" by Melissa Tandiwe Myambo and "Hunter Emmanuel" by Constance Myburgh.

Both are solid stories with their own virtues and are, much to the jurors' credit, utterly different from each other.

"La Salle de Départ" tells the tale of a sister who has remained at home while her brother was sent to school in America; he returns home for a visit having become relatively successful in the States, engaged to an Egyptian woman who is a liberal Muslim and a scholar, and unable to relate to his own family anymore. It's true, in this story, that you can't go home again. The cultural and economic divides are nicely delineated, and this is a generally well-written story, carefully structured and balanced, a story with clear themes and unresolved tensions and psychological probing and sociological gesturing, a story that, of course, has an unresolved, dying-fall sort of ending. It's what I think of as a safe workshop story — a story that demonstrates plenty of talent and sensitivity and gives everybody around the table something to comment on and admire. It's also the sort of story that flatters its readers: we can feel good about our own sensitivities after reading it, because we have sided with the good character, we have identified the tensions, we have appreciated the dilemmas, we have nodded our head at the seriousness of it all, and we have felt the proper emotions.

And as you can probably tell from my tone, it's not a type of story I have much interest in. It's worth reading, it's even perhaps worth nominating for an award, but I just struggle to muster a lot of enthusiasm for a story that is so determined to be good for me.

"Hunter Emmanuel", on the other hand, is not a story that wants to be good for anybody. It is a deliberately pulpy tale, originally published in Jungle Jim, "a bimonthly, African pulp fiction magazine" or "genre-based writing from all over Africa." The story is certainly pulpy and hardboiled, but not in a nostalgic or posturing way. The genre feels utterly appropriate for the setting and events. Rewriting the story in a different idiom would rob it of all its meaning.

It's a story that begins with a severed leg in a tree. Hunter Emmanuel is not a fairy tale character (which I assumed when I first saw the title), but an out-of-luck former police officer who has become a lumberjack. He finds the leg, and can't help but start an investigation on his own. What he finds surprises him. He's fine at getting to what happened, but he's not very good at understanding other people's motivations and desires.

The world of the story is dark and grimy, but there's a dream-world underneath it all, or at least underneath Hunter Emmanuel's perception of it all. A wonderful lyric passage in the middle of the story begins:

That night Hunter Emmanuel dreamt of corridors and mermaids, of seal women. Trees that stretched on and on, up and up, trunks wider than ten men's arms could reach around. Solid pine. It was no good. He'd spent enough nights similarly to know he couldn't sleep like this.Unable to sleep, he goes out into the world, dragging h

Blog: Anwers from digital publisher (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: authors, WRITING, people, novels, world, word, genre, Answers, literary text, Add a tag

Empire and Rce. Answers from Anya Tretyakova. H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness are two Victorian novels, which despite differing greatly in subject matter and genre, nevertheless share many common tropes that bear further examination. The Time Machine, a work of Science Fiction, one of the earliest of its kind, sees the protagonist on a journey through time; seemingly travelling into the future, yet encountering a planet and inhabiting ‘civilisation’ which instead appears to be regressing into prehistory with the passage of time. Heart of Darkness, a symbolic, frame narrative is harder to place in terms of genre, but can be read as a transitional text between Victorian and Modernist styles; here, the protagonist is also on a journey, which even though it is only through physical space, has all the hallmarks of pseudo-time travel. In Heart of Darkness, the protagonist, Charles Marlow journeys into Africa, ... Read the rest of this post

Add a CommentBlog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: genre, audience, writing wednesday, Add a tag

The problem of categorization doesn't go away in the coming e-book utopia where we won't be limited by traditional bookstore shelving constraints. In fact, the always-on world of digital media multiplies the opportunities (or demands) to know what other books your is like.

So, how can you confidently determine the genre of the book without reading every other genre? The good folk at Book Country have produced an interactive genre map. (The example here is only an image.) Click on a genre to see a list of representative books.

So, how can you confidently determine the genre of the book without reading every other genre? The good folk at Book Country have produced an interactive genre map. (The example here is only an image.) Click on a genre to see a list of representative books. One of the ways to use the map is as a guide for your reading. Once you've chosen which of the five general genre feels most like home, go through the sub-genres and make sure you've read at least one book in each list.

Still not sure where your book belongs because it's a thrilling romantic mystery set in a future where a technological society battles medievaloid magic users? Try the exhaustive, pair-wise comparison exercise: for each pair of genres, if you can only choose one, which genre best characterizes your book. Then tally up the winner for each pair. The genre with the highest score is your primary genre.

I should point out that the genres in this map are for adult fiction. Young Adult and Middle Grade books can be classified in similar terms, but were, until recently, all shelved together. Barnes & Noble now has different shelves for YA genres like paranormal. In other words, while genre boundaries aren't quite as strictly drawn in children's literature, you can't ignore the question.

Deren blogs at The Laws of Making.

View Next 25 Posts

Much of what I write is historical, or at least is set in historical times, even if it doesn't explore real historical events.