new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: symbolism, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 12 of 12

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: symbolism in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Wow, you guys. What an amazing week!

A huge thank you to everyone who participated in our big ROCK THE VAULT giveaway and to all those who shared the #myfavoritethesaurus pictures. I think we made thesauruses everywhere officially COOL. And also an enormous thank you to all the wonderful people who helped out with our launch, especially the Thesaurus Club (our street team). We are so blessed to have so many wonderful people support us. If you want to find some of these folks and their blogs, check them out here.

While we didn’t get to the 500 pictures shared that would unlock all prizes in the vault, we did see about 300 of them online, and so Angela and I, being the softies we are, unlocked most of the prizes. Winners have been drawn and are being notified. Once we have acceptance from these lovely people, Angela will post the list.

While we didn’t get to the 500 pictures shared that would unlock all prizes in the vault, we did see about 300 of them online, and so Angela and I, being the softies we are, unlocked most of the prizes. Winners have been drawn and are being notified. Once we have acceptance from these lovely people, Angela will post the list.

And for those of you who happened to buy our new books this week, thank you for welcoming our youngest offspring into the world! We hope that you have many light bulb moments when it comes to description and maximizing your settings.

They grow up so fast. *sniff sniff*

While Rock the Vault was a blast, Angela and I would be lying if we said we weren’t looking forward to getting back to a more normal routine. And today, that means me posting at the unbelievably awesome Kristen Lamb’s blog.

If you’re not familiar with Kristen, rectify that posthaste by following her on every conceivable social media platform. She’s one of the most prolific and knowledgeable bloggers out there as well as being an expert on all things networking and branding. If you’ve got a few minutes, drop in and see how Symbolism and the Setting Make a Perfect Marriage.

Happy Writing!

Save

Save

The post Settings and Symbolism appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS™.

Try Book 1 for Free

There’s an apocryphal story about a writer who worked hard all day. In the morning, he inserted a semi-colon; in the afternoon, he removed a semi-colon.

This morning, I inserted a metaphor; this afternoon, I removed the metaphor.

Metaphors continue to be a thorn in my side. I appreciate when I’m reading a story or novel and there’s an apt metaphor. It adds to my enjoyment because it expands the story and creates new connections. Such glimpses into the thought process of another human are one of the joys of reading.

Yet, when I sit down to write, I’m practically metaphor free. Partly, it’s because I find it tedious to sit down and add metaphors just because someone says my prose would improve with the use of metaphors. But as I’ve thought about it more, I’ve decided my problem is the difference in dominant vs. scattered imagery.

Dominant vs. Scattered Imagery

In their work of genius, How Does a Poem Mean, Miller Williams and John Ciardi discuss “The Image and the Poem” in Chapter 6. I refer you to their book for a full discussion of imagery, metaphors, similes and so on. For my purpose, though, let me concentrate on the question of dominant and scattered imagery. Here’s what Williams and Ciardi say:

“When the images of a given poem, or of a given passage, are related by their denotations, that poem or that passage is said to be constructed on a dominant image. When the images are related by their connotations but range widely in their denotations, that poem or passage is said to make use of scattered imagery.” (p. 247)

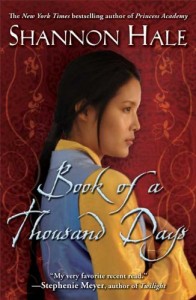

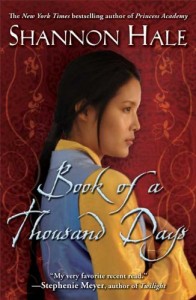

Here are some imagery (metaphor/similie) from Shannon Hale’s Book of a Thousand Days

Here are some imagery (metaphor/similie) from Shannon Hale’s Book of a Thousand Days

- P. 1 I feel like a jewel in a treasure box. . .

- p. 2 Stay until your heart softens like long-boiled potatoes. . .

- p. 2 . . .skinny as a skinned hare.

- p. 8 It (the candle flame) tosses and bobs like a spring foal. . .

- p. 11 My heartache felt like a river, and I was sinking into it, carried away fast in its coldness.

- p. 12 . . if all they find is a delicate lady and her humble maid shriveled like ginger roots

- p. 13 I feel like a mucker from the ends of my hair to the mud of my bones.

- p. 13 It (lord’s house) was near as beautiful as a mountain in autumn. . .

- p 15 she sat on her bed, alone, straight as a tent pole

- p. 16. . . they resembled my own deel (clothing)as much as a worm resembles a snake.

- p. 18 . . . my lips thinner than the edge of a leaf.

- p. 18 He slapped his daughter’s face. . . like a snake striking.

- p. 20 She (Lady Saren) reminded me of a lamb just tumbled out, wet all over, unsure of her feet and suspicious of the sun.

Taken together, they don’t create a dominant image; Hale is using scattered imagery in a masterful way. Each image is directly related to the immediate situation. They don’t add up to a bigger image at the end—the collection of images don’t combine to create any symbolism.

Most of the time, when people mention the need for more metaphors in a piece, they mean this sort of scattered imagery.

However, when I write, I tend to write for a dominant image, using symbolism more than metaphors. The principle of selection of details for me is a wider scale. I’m looking for imagery that spreads across a whole chapter or even a whole novel.

Miller and Williams call this an overtone theme. (p. 110) They analyze the themes in a selection from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, concluding that Milton chose words and images based on two themes to describe the Biblical serpent who visited Eve: watery motion and regal splendor. A third category is when the two themes mesh.

Here’s a catalogue of the language:

- Watery Motion: indented wave, circular base, rising folds, fold upon fold, surging maze, floated redundant

- Regal splendor: carbuncled, burnished, gold, circling spires

- Combination of water and regal: towered, crested aloft

They say, “Whatever the value of such a tabulation, it cannot fail to make clear, first, that a unified principle of selection is at work in this diction, and second, that the words are being selected from inside their connotations and in answer to one another’s connotations, rather than from inside their denotation.”

Milton chose words/phrases because when they banged up against another word/phrase, they changed each other slightly. Circling spires weren’t just an architectural delight; instead, they hinted at regal splendor.

When I write, this is what I’m trying for: connotations speaking to connotations. I hope that I create a cumulative dominant image. I choose words based on certain themes and then work to make them collide.

Tips on Scattered Imagery

One reason I’m not fond of scattered imagery is that in the hands of a novice, it jerks me out of the current story. Here’s an example.

Setting: The principal tells you that you’ve won a scholarship, but to get it, you must accept an exchange student into your home for a year.

“. . . awesome news tossed into her lap like a grenade.”

Setting: A girl is thinking about a weird boy.

“ Thinking about him made her stomach hurt like she’d eaten a dozen McDonalds burgers at one sitting.”

These similes are easy to understand, contemporary, and not my favorite. In the first situation, a grenade carries the connotation of war, shock, and a shattered body. It’s too much for my taste because it pulls me out of a teen novel and instead, puts me in the Vietnam or Iraqi War.

In the second situation, I certainly understand that a dozen burgers (from anywhere) eaten in one sitting would give you a tummy ache. But how does this relate to the situation? It didn’t relate for me.

Hale sticks to imagery related to the immediate scene.

Setting: The princess and her maid are forced to become scullery maids in order to eat.

“Stay until your heart softens like long-boiled potatoes. . .”

In a kitchen setting, this makes sense. It also relates to the character who comes from the country and is familiar with the humble potato.

When you use scattered imagery, then, especially metaphors and similes, give them deep roots in the setting, not just a reference to a general cultural region.

And when you critique writing for others, remember the range of possibilities. Certainly, I always need to be challenged to use deeper imagery; but maybe, I don’t need to worry so much about just the one option for imagery called the metaphor.

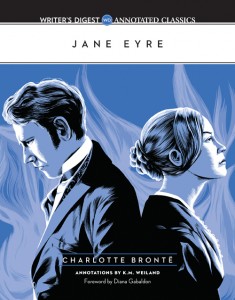

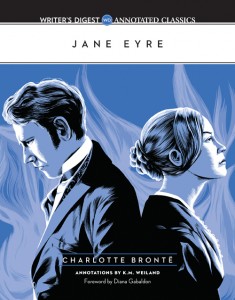

So many elements go into a truly good book. When we turn that final page with a satisfying sigh, it’s often hard to identify just what made it a success. But many times, symbolism is one of the things that ties the whole work together. Done sloppily, it’s heavy-handed and forced, and turns the reader off. And when it’s done well, symbolism is one of those elements that the reader doesn’t notice; they just recognize that everything worked. It’s an important element, but really hard to do well. That’s why I’m glad to have K.M. Weiland here today. Symbolism is just one element that she tightens the focus on in her latest release: Jane Eyre: Writer’s Digest Annotated Classics . I had the pleasure of reading this arc, and it was so incredibly interesting, seeing a classic analyzed to see what made it a success. It frankly would have scared the poo out of me, being the one to pick apart such an iconic, well-known novel, but Katie totally nailed it. So rather than blather on, I’ll just turn things over to the expert ;).

. I had the pleasure of reading this arc, and it was so incredibly interesting, seeing a classic analyzed to see what made it a success. It frankly would have scared the poo out of me, being the one to pick apart such an iconic, well-known novel, but Katie totally nailed it. So rather than blather on, I’ll just turn things over to the expert ;).

Symbolism can sometimes be a tough concept for authors to get their heads around. How do we come up with the right symbols in the first place? What should they be symbolic of? And how do we incorporate them into our stories without making them so obvious we lose all their symbolic value?

Symbolism offers one of the richest opportunities for writers to deepen their themes, past just the conscious appreciation of the readers and right into their emotional and subconscious cores. That’s a lot of power right there. And we’d be crazy to leave it on the table.

Charlotte Brontë’s classic masterpiece Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic) is a wealth of symbolism. You want to know how to do it right? All you have to do is learn at Brontë’s feet. Following are five methods of symbolism she used to enhance every aspect of her story—and which you can use too!

Charlotte Brontë’s classic masterpiece Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic) is a wealth of symbolism. You want to know how to do it right? All you have to do is learn at Brontë’s feet. Following are five methods of symbolism she used to enhance every aspect of her story—and which you can use too!

Symbolism Type #1: Small Details

You can include symbolism in even the smallest of your story’s details. The colors your characters wear. The movies they watch. The pictures they use to decorate their apartments. All of these details offer the opportunity for symbolic resonance.

In the first chapter of Brontë’s story, Jane Eyre is reading a book called Bewick’s History of British Birds, which features significantly bleak and desolate descriptions of the English landscape. On the surface, these descriptions have no connection to Jane’s world—except that, of course, they do. Brontë could just as easily have given Jane a cheery romance to read. Instead, she used the bleak descriptions to symbolize Jane’s bleak life as an orphan living with her cruel aunt.

Symbolism Type #2: Motifs

A motif is a repeated design. In a story, a motif is an element repeated throughout the narrative, often to obvious effect. Sometimes, however, it will be used in a less conspicuous way that infiltrates the readers’ subconscious with a web of symbolic cohesion.

The concept of orphanhood is prominent throughout Jane Eyre, most notably in the main character’s own status as a loveless orphan. Indeed, the concept of love and what people have to do to earn it is central to the entire story. Brontë reinforces the obvious aspects of this motif time and again throughout the story. Consider just a few examples:

- Early on, a servant sings a song about an orphan girl.

- Adele, the child Jane is hired to look after, is ostensibly an orphan.

- When Jane encounters the Rivers family, late in the story, she discovers they are newly orphaned themselves, after the death of their father.

Brontë never draws attention to the motif by directly comparing these examples to Jane’s own orphaned state. Rather, she simply allows their presence in the story to reinforce the overall effect.

Symbolism Type #3: Metaphors

Motifs can also be metaphors. Indeed, some of the best symbols in literature are visual metaphors for thematic elements. You may choose to use fire to represent a character with a hot temper. Running water may become a symbol for purification. Illness might represent sin or corruption.

The main metaphoric motif in Jane Eyre is that of birds as symbols for captivity and freedom. Brontë uses the bird metaphor throughout the story to symbolize the relativity of every character and setting in relation to this fundamental theme. Small, plain birds such as sparrows represent Jane. Birds of prey refer to Rochester. And Thornfield—Rochester’s prison and Jane’s sanctuary—is frequently described in terms of a bird’s cage.

Often, strong metaphoric language will emerge naturally while writing a story. In the rewriting, see if you can identify any recurring motifs that crop up. Can you strengthen them to better represent your theme? Try to figure out ways to use different aspects of the same motif to describe varying characters.

Symbolism Type #4: Universal Symbols

Some symbols are ingrained so deeply in our social psyche that they are used in practically every story. The power of these symbols lies in the fact that they will already have been accepted deep into your readers’ subconscious minds. (Their potential weakness, of course, is that their very prevalence can make them seem like clichés.)

Weather is a particularly good example. Thunderstorms are often used as the background for a character’s defeat—or as a contrast to a seeming victory. When Jane accepts Rochester’s proposal, the lightning that strikes a tree in the garden isn’t just a random happening. It’s a portent of the dark revelations that will soon sunder their love.

Symbolism Type #5: Hidden Symbolism

Some types of symbolism will be so deeply buried within your story that your readers may not recognize them at all. Obviously, the value of hidden symbolism is significantly less than that of other types. After all, what good is something if the reader never notices it?

For example, Rochester’s horse is named Mesrour. Very few readers will catch the significance of this: Mesrour is the name of the executioner in Arabian Nights.

Why name the horse this at all? Why not Blackie? Or even O Beauteous One? For starters, both of the latter names would have been a poor use of our Symbolism Type #1. “Mesrour,” even without explanation, enhances the already dark and mysterious tone of the novel. And for those readers who do catch the obscure reference, the symbolism will only be that much stronger.

Symbolism is a delicate dance. But authors can’t afford to overlook it. When choreographed correctly, it can spell the difference between a three-star novel and a five-star novel. Just ask Jane!

K.M. Weiland lives in make-believe worlds, talks to imaginary friends, and survives primarily on chocolate truffles and espresso. She is the IPPY and NIEA Award-winning and internationally published author of the Amazon bestsellers Outlining Your Novel and Structuring Your Novel. She writes historical and speculative fiction from her home in western Nebraska and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

K.M. Weiland lives in make-believe worlds, talks to imaginary friends, and survives primarily on chocolate truffles and espresso. She is the IPPY and NIEA Award-winning and internationally published author of the Amazon bestsellers Outlining Your Novel and Structuring Your Novel. She writes historical and speculative fiction from her home in western Nebraska and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

The post 5 Important Ways to Use Symbolism in Your Story appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

When a first draft is slightly off in the Show-Don’t-Tell of a relationship, how do you correct the relationship? Three places in a story can be tackled.

Direct confrontations. When characters interact, it’s relatively easy to adjust a character relationship to heat it up or cool it down. The exact wording of dialogue can change: “That was mean.” v. “I hate you.” In both cases, the speaker may hate the other person, but what they actually said was a reason for the hatred. These wordings must exactly give the impression you want for this relationship. Further, you can build in progressions of similar comments throughout the story to indicate the changes in the relationship.

Talking about a character. If only A is present, we can still learn about A’s and B’s relationship by the way the A thinks about B, or how A tells someone else about B. Again, both denotation and connotation are important. Within the context of the story, words take on extra meaning or connotations. For example, in a story about cowboys, most discussions of horses would take on an affectionate tone. Comparing a working relationship to a cowboy’s relationship with his horse would be a good connotation. Comparing a working relationship to a cowboy who comes up on a rattlesnake, well, that’s bad.

Talking about a character. If only A is present, we can still learn about A’s and B’s relationship by the way the A thinks about B, or how A tells someone else about B. Again, both denotation and connotation are important. Within the context of the story, words take on extra meaning or connotations. For example, in a story about cowboys, most discussions of horses would take on an affectionate tone. Comparing a working relationship to a cowboy’s relationship with his horse would be a good connotation. Comparing a working relationship to a cowboy who comes up on a rattlesnake, well, that’s bad.

Symbolism within a story. Finally, within a story, certain objects or events can carry a symbolism that reflects back on the character relationship. For example, in a story about a father and daughter, a symbolic moment might be a description of a bird forcing its chick to fly for the first time. You don’t have to explicitly connect the flying with the father-daughter relationship; instead, the reader will understand that the father is only trying to make the daughter grow up.

If you’re working on a character relationship, work on all three levels, not just one. Adjusting only one will leave the reader unsure what you meant. Make sure you are controlling what the reader understands and feels.

This is a formula learned by Stephen King back in his early years of multiple (multiple!) rejection slips. Like Mr. King, I find my writing style to be the opposite. I write a fast paced, skimpy first draft, and then add the meat later. But I'm just now figuring out what that really means.

I'd worry about themes, and character arcs and motivations, all of the things a good writer should be worried about. But I'm realizing now that I think I worried about them at the wrong time. I don't outline. I don't plot my first draft. I can't. I've tried, and it kills my creativity. Just...*bang*. Dead. I start with something--a situation, a character, a first line--and I go with the flow from there. Granted, I would probably save myself some revision time if I thought ahead, but that's just not how I work. I'm noticing now as I'm on draft # (I care not to mention the number) that I DO have themes! Or at least, snipits of things that I can make resonate, things I can flesh out and bring to the foreground and make thematic! OMG! And I have symbolism! What!? For real. It's all there. And I didn't even try.

I wish I'd come to this revelation sooner, and had I finished this amazing book called On Writing a little sooner, I probably would have. But I'm not one to dwell on shoulda, coulda, woulda.

I'm not saying every story needs themes or symbolism nestled in there. I don't think they all do, but if you find it, go with it. Why not, right?

Another question we tend to stress over is the "what's it all about?". What was my book all about? What was I trying to say with it? Why did I spend so many hours hunched over my keyboard, forgetting to eat, or shower, or wear suitable clothing? This is another question best saved for draft #2, not the first draft. At least, in my case. I can't speak for the rest of you.

During the first draft stage, you might keep this one tucked away in the back of your mind, I try to. But I personally can't decide what I want to say until it's done. You don't want to sit down before you write and think to yourself, "Well, I'm just going to teach these kids that doing drugs is a bad idea." Because then your manuscript of going to reek of morality. And if you want to write an honest work of fiction, you don't want to do that. I mean, unless that the sort of book you want to write. I don't want to step on any toes or anything.

So that's basically it. Often bringing these things to light in what you've already written takes a great deal of cutting (killing those pretty little darlings) and moving, shaping, rewriting. But when you sit back and read what you've written, and it actually resembles a real story, it's so worth it.

Does anyone here follow this formula? Start of with a whopper and file it down to the good stuff? Please share!

By: Julie Daines

When I was a kid, my mom had this crazy wallpaper in one of our bathrooms. It was black and white, and covered in pictures of cartoon people poised by outhouses—all kinds of outhouses, in trees, on beaches, in the woods.

Whenever I went in that bathroom, I’d stare at the wallpaper until I noticed something different, some tiny detail that I hadn’t seen before. The older I got, the harder I had to look, but eventually, I always found something.

One of my main characters in my current work in progress is blind from birth. It’s been a real challenge trying to “see” the world from her point of view. I’ve blindfolded myself just to see how long I could go without using my vision. It hasn’t been very long. I had a terrible hair day and typed several paragraphs with my fingers on the wrong keys.

But I did learn to pay attention to the other senses, and how those other senses make me feel. So, take a second and learn to notice.

Close your eyes in the shower. What does the water feel like when it hits your back? Your face? Does it relax you? Or hurt? (I’ve stayed in a friend’s house where the shower pressure was so strong the water stung. We had to cover the showerhead with a sock to diffuse the powerful spray.)

What does it sound like when you unload the dishwasher? Or start your car on these freezing cold mornings? What can you hear in bed at night? From my house, I can hear the train whistle—but only at night. It comforts me.

Take a bite of a food that you hate and focus on why it is you hate it? Is it the texture? Or the taste? Or does it remind you of hospital food? Close your eyes and run your hands over your desk. Or over your family’s faces. I’ve done that a lot recently, and it’s an interesting experience.

It’s these details that add life to our stories. We all know this, but sometimes, when we’re writing we get bogged down in the plot and our characters, and miss out on the opportunity for some great sensory details.

These details gain value as they often become the source symbolism and themes, and carry unifying motifs throughout the story. A splinter in the finger that grows, festers, and is finally removed. The smell of mom's bacon and eggs luring the family out of bed--until the mom dies, taking that smell with her. The touch and swish of a girl's first silk party dress becomes symbol of her coming of age.

What makes you love your WIP? Is it the characters? The plot? The premise?

For me, it's a combination of the above, but it's also that indefinable magic that suddenly makes symbols and images appear in the writing without my knowledge, the overarching, structural metaphors and symbols that bring disparate elements together and illuminate what the story is about. Often I don't have any idea where they come from. Sometimes they are purely conscious. Either way, they form the connective web between the images, themes, characters, and settings. They're the unifying force that gives life to the work, and the surprise and delight I find when they work is a big part of what makes writing--and reading--fun.

As writers, we have a whole arsenal of tools we can use to deepen our work and engage readers on additional levels. Among other things, we use:

- establishing or anchoring images to set a scene.

- closing images to underscore tone or heighten emotion.

- symbols to build a wordless emotional vocabulary.

- figurative language to simplify explanation at the sentence or paragraph level.

- recurring symbols or echoes to draw attention to a theme.

- recurring images to underscore turning points, build emotional intensity, point to what characters are feeling or thinking, or make a characters voice unique.

Chaining or repeating symbols, metaphors, or images together can be one of the simplest and most powerful ways tie scenes or subplots together.

Symbols, imagery, and figurative language are usually simple to spot and identify, but there are so many different kinds it an be hard to remember that we have a much wider range of tools than we commonly use. Each type is unique, but each is an important in shaping our language, pages, scenes, chapters, and overall work.

- Establishing Shots: Usually discussed in reference to film or television, establishing shots work beautifully in written form to set up the context of a scene. In addition to providing the traditional elements of setting, they create the relationships between the characters and objects in the setting. You can build them through a quick, straight description at the beginning of your scene, but figuritive language or symbols can make them especially powerful. Think of every scene as a scene in a film, and provide an establishing shot for each.

- Anchoring Images: An image for your readers to visualize as they move through the scene. Judicious use of props and actions can link establishing shots and various anchor images within a scene to make it play out as visually as a film.

- Concluding Image: Underscores the emotional note of a scene and resonates with the reader longer. By using a powerful concluding image, you can say much less explicitly and achieve a greater payoff.

- Symbols: Derived from the Greek word for "throw together" symbols draw invisible comparisons to bring additional layers of meaning into your work. Angela Ackerman has a brilliant symbolism thesaurus on her blog, the bookshelf muse: http://thebookshelfmuse.blogspot.com/2010/02/new-symbolism-thesaurus.html.

- Similes: A type of figurative language that explicitely compares one things to another using the words 'like' or 'as.'

- Lips as red as roses

- Cheeks as white as snow

- Reeling her in like a fish on the line

- Simple Metaphors: At their most basic, metaphors use a handful of words to liken one thing to another without explicitly saying they are alike.

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 4/30/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

characters,

child,

baby,

suspense,

how to write,

tragedy,

write a novel,

symbolism,

jeopardy,

character's death,

death scene,

emotional depths,

fully characterized,

Add a tag

Does Your Story Need a Tragic Death?

A friend was talking to me about stories in which a child dies. he asked, “Is a child’s death in a novel just a cheap narrative device?”

Well, it depends.

- Depth of Characterization. How well do we know the character? Do we know and care for the child? Does the story involve the child and his/her hopes dreams in any way? If we care for a character, we’ll be more likely to be emotionally affected by the death; and it will seem more like a part of the story and not just a cheap narrative device.

- Minor v. Major characters. If a minor child character dies, a throw-away character, the audience won’t care much, unless you’ve given the character big eyes with long eyelashes. But even that bit of specificity in the middle of a scene might not make the reader care. Because it’s a kid, it may be worth some shock value, and killing a kid simply for shock value does count as a cheap narrative trick.

- Suffering, jeopardy, suspense. Has the character suffered or does this come out of nowhere? Orson Scott Card talks about jeopardy, putting a character into a position where there is danger, and suspense, holding back only what happens next. It may be enough to put a child in increasing jeopardy, where things are dangerous, but the character must still act. Or, it may be enough to built a suspenseful scene where we worry about what happens next. Some death scenes could be replaced with either of these and still be effective

- Symbolism of a child’s death. Does the death of a child represent the loss of innocence and faith in the future? Depends. How did you set up the symbolism of THIS child? I don’t think you can generalize here, because the language used to describe the child, the actions of the plot – these can all affect symbolism. To say that a child’s death always equals loss of innocence is too glib an answer.

- Author’s Tolerance for Death. When Leslie dies in Bridge to Terabithia, it’s tragic and awful; I didn’t feel like the author had tried to manipulate my feelings, it was just a horrible accident. But I once went to a conference where an author was talking about the death of a child when it occurs in a story. The author said she hated going to schools, where kids would inevitably ask, “Why did so-and-so have to die?”

Tired of the plaintive question, she decided to never write another story for kids in which a child died. She was in the process of writing a story where a baby was sick and in the hospital. With her decision made, she started working on the next chapter and wrote, “The baby opened her eyes.”

Was she protecting herself from the questions? Was she protecting her audience from the emotional depths to which stories can take a reader? Was she protecting the baby? I don’t know.

In the end, you have to decide where you and your stories will fall: will you allow tragedies, even to the point of death; or will you hold back to protect yourself, your readers and your characters? What does the story tell you to do?

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

No related posts.

While we didn’t get to the 500 pictures shared that would unlock all prizes in the vault, we did see about 300 of them online, and so Angela and I, being the softies we are, unlocked most of the prizes. Winners have been drawn and are being notified. Once we have acceptance from these lovely people, Angela will post the list.

While we didn’t get to the 500 pictures shared that would unlock all prizes in the vault, we did see about 300 of them online, and so Angela and I, being the softies we are, unlocked most of the prizes. Winners have been drawn and are being notified. Once we have acceptance from these lovely people, Angela will post the list.

I definitely have a problem with putting WAY too much in my 1st draft--then I feel sad when I have to cut scenes out during revisions. I always find it helpful to start revisions in a completely different file; that way, I'll have deleted scenes saved and could possibly use them in the future (even if it's for a different story). Great post! :)