By David Rothery

There’s a Patrick Moore-sized hole in the world of astronomy and planetary science that is unlikely ever to be exactly filled. He presented “The Sky at Night,” a monthly BBC TV astronomy programme, from 1957 until his death. This brought him celebrity, and the books that he wrote for the amateur enthusiast were bought or borrowed in vast numbers from public libraries for half a century — including by myself as a schoolboy. Patrick was the mainstay of the BBC’s Apollo Moon-landing coverage that those of us of a certain age will never forget, and there can be few amateur or professional astronomers who grew up in the UK without having been influenced by him. Tributes posted on the Internet show that he was known and admired beyond these shores too. They also attest to Patrick’s extraordinary generosity, exemplified by numerous accounts of how he replied to letters from strangers (of whom in the early 1970s I was one) or took time to chat after his lectures.

Patrick served with distinction and under age as a navigator with Bomber Command during the war. I believe (on the basis of dark hints made during late night conversations) that he also spent time on special operations in occupied Poland, where his youth and assumed Irish identity afforded him a plausible (but surely high-risk) cover story. An encounter with what he referred to as ‘a working concentration camp’ led to his lifelong professed dislike of Germans (“apart from Werner von Braun, the only good German I ever met”).

After the war, Patrick became a school teacher and also very active in the British Astronomical Association notably in its lunar section on account of his painstaking and careful observations of the Moon, some of which were to prove useful for both the American and Soviet lunar missions. He became a friend of the science fiction visionary Arthur C. Clarke, with whom he shared the authorship of Asteroid (2005) sold in aid of Sri Lankan tsunami relief.

I first met Patrick when we were speakers at a meeting to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of Neptune, so that must have been 1996. He spoke about Neptune itself, and I about its main satellite Triton. Afterwards he was kind enough to remark that he had read my book (Satellites of the Outer Planets). Our first joint TV appearance was “Live from Mars,” an Open University TV programme on a Saturday morning in 1997 when NASA’s Mars Pathfinder landed, allowing us to broadcast the first new pictures from the surface of Mars for nearly 20 years. I became an occasional guest on “The Sky at Night” more recently, which led to a friendship, as with so many of his guests. The programme was usually recorded at Patrick’s home in Selsey, and Patrick delighted to put his guests up overnight, rather than send them to a nearby hotel. That was a cue for an impressively-laden supper table, copious quantities of lubricant, and entertaining — if sometimes outrageous — conversation. Patrick had a wry sense of humour, and would self-parody his supposed extreme views. However, I think he was being serious when, or several occasions, he styled a certain recent US President as “a dangerous lunatic”.

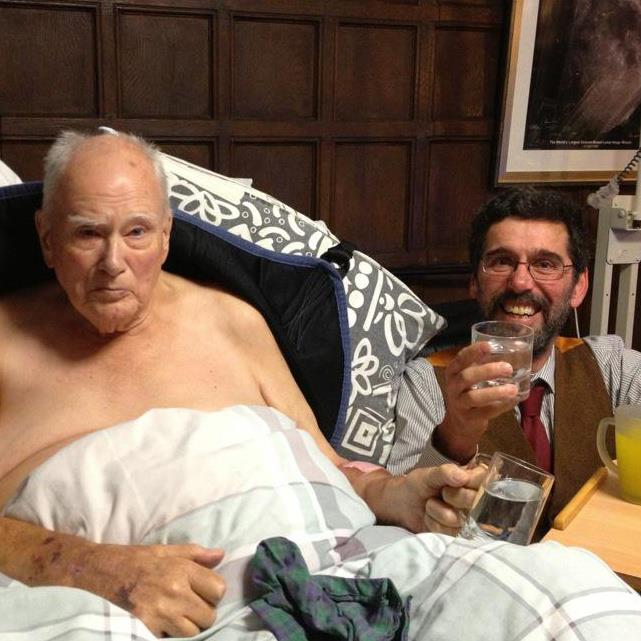

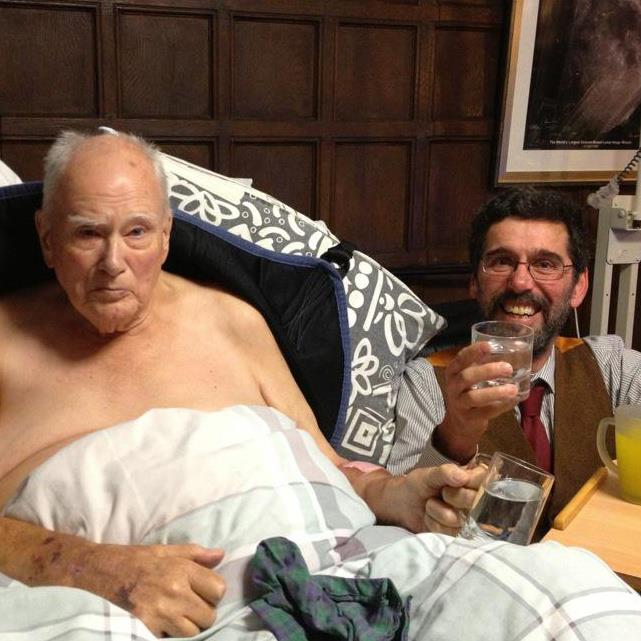

I witnessed Patrick’s mobility decline from walking sticks, to zimmer frame, to wheelchair. His once famously rapid speech became slurry, but his mind and monocle-assisted eyesight stayed sharp. Co-presenters assumed larger and large roles on “The Sky at Night,” but Patrick was always there as the pivotal host. I last saw him less than three weeks before his death, when I guested on what was to prove his last “Sky at Night.” He was drowsy at first, but his intellect soon kicked in. He steered our discussion as ably as of old, and we were treated to a vintage Patrick moment of scepticism “When someone gives me a cupful of lunar water, then I’ll admit I was wrong.”

I lingered afterwards for a chat — inevitably partly about cats. Noticing the time, Patrick ordered a gin and tonic for each of us, and was soon involved in good-natured banter with his carer about why she would not let him have a second. He encouraged me to write a book about Mercury, and kindly agreed to write the foreword if I did. That’s an offer that I shall no longer be able to take him up on, but wherever you are, Patrick, I hope someone’s brought you that cupful of lunar water by now.

Sir Patrick Moore

4 March 1923 – 9 December 2012

Patrick Moore with David Rothery earlier this year.

David Rothery is a Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the Open University UK, where he chairs a course on planetary science and the search for life. He is the author of Planets: A Very Short Introduction.

Image credit: Image is the personal property of David Rothery. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of David Rothery.

The post In memoriam: Patrick Moore appeared first on OUPblog.

Megan Branch, Intern

Patrick Wright a Professor at the Institute for Cultural Analysis at Nottingham Trent University and a fellow of the London  Consortium. Wright wrote On Living in An Old Country and its companion, A Journey Through Ruins: The Last Days of London (read an excerpt here). On Living in an Old Country looks at history’s role in shaping identity and everyday life in England. Below is an excerpt about the house of Miss May Alice Savidge. Upon finding out that her pre-Tudor house was scheduled for demolition to make way for road work, Savidge dismantled it, shipped it 100 miles away, and began reassembling the house piece-by-piece.

Consortium. Wright wrote On Living in An Old Country and its companion, A Journey Through Ruins: The Last Days of London (read an excerpt here). On Living in an Old Country looks at history’s role in shaping identity and everyday life in England. Below is an excerpt about the house of Miss May Alice Savidge. Upon finding out that her pre-Tudor house was scheduled for demolition to make way for road work, Savidge dismantled it, shipped it 100 miles away, and began reassembling the house piece-by-piece.

On Camping out in the Modern World

“History appears as the derailment, the disruption of the everyday…” - Karel Kosik

So far I have not identified the political complexion of the local authority in Ware, not for that matter of the national government when the decision to redevelop Miss Savidge’s home was made. This has not been the result of any reluctance to deal with the political implications of Miss Savidge’s story. On the contrary, my point is that these implications will not be appreciable unless one also grasps the extent to which politics, at least in the traditional frame of the major electoral parties, have become irrelevant to the issues finding expression in this affair.

In a phrase of Habermas’s, the political system is increasingly ‘decoupled’ from the traditional measures of everyday life, and Miss Savidge cannot be adequately defined as the victim of one party as opposed to another. She fell instead (and, of course, rose again) on the common ground of the post-war settlement, a ground which is made up of rationalised procedures and methods of administration as much as of any shared policies about, say, the efficacy of the mixed economy or the legitimacy of the welfare state. Miss Savidge’s house stood in the way of an ethos of development and a practice of social planning and calculation which have formed the procedural basis of the welfare state under both Conservative and Labour administrations. Governments have come and gone (at the behest of an electorate oscillating at a rate which itself reflects the situation), but a professionalised conduct of social administration has persisted throughout.

The professionals of this world are almost bound to see the more traditional forms of self-understanding persisting among the citizenry as merely quaint and eccentric, if not more dismissively as obstructive and inadequate to modern reality. While there is always room for an arrogant contempt to develop here, the most frequent manifestation consists of a resigned and pragmatic realism (the bureaucratic sigh which responds to people’s demands by saying that things are always more complicated than that) with which officials draw out and exhaust the discussion and patience of residents’ associations around the country. That this system of planning is less than perfect goes without saying, and Miss Savidge is well stocked with complaints on this score. For anyone who stops to ask she will talk about the callousness of the officials who turned up the Saturday before Christmas (1953) to look at the buildings which they had already decided to pull down—even though this was the first the residents had heard of it. She will mention inconsiderate rules applying to council tenants (no cat or dog unless you have a family, and so on). She will also talk about a general bureaucratic incompetence which, in her experience, made it possible to get a council grant towards the cost of installing a bathroom in a house which was already up for demolition, and which was also evident in the many changes of plan regarding the road development itself. Is it to be a new road with a roundabout, or can the old road be widened, and which local authority (town or country) is to be responsible?

Bureaucratic procedure may indeed be conducted as if its rationality were contained entirely within its own calculations, and in this respect it may well seem to stand impervious: free from any responsibility to the world in which its works eventually materialise. But whatever the appearance, this is obviously not a matter of rationality alone. The system of planning into which Miss Savidge was well caught up by 1969 is characteristic of a welfare state that was both corporatist in character (public discussion and political negotiation simulated in thoroughly institutionalised forms), and caught in the contradictions of its commodifying pact with private capital. More than this, the welfare state has developed through a period of extensive cultural upheaval, and Miss Savidge’s is therefore a story of the times in its discovery of tradition not just in the lifeworld but also in an apparently hopeless contest with modernity. While the dislocation of traditional self-understanding could indeed prepare the way for better possibilities, Miss Savidge stands there as a testimony to another scenario in which the prevailing atmosphere is one of insecurity which develops when extensive cultural dislocation has occurred without any better, or even reasonably meaningful, future coming into view.