new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: slush, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 21 of 21

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: slush in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

A note: This post was written in February and programmed here to fill a hole in my programming. Normal blog posts will resume in the next few weeks, but I just wanted to put some fresh material online!

Recently, I worked with a client who had written, by all accounts, a middle-grade novel. It has fantasy elements, an eleven- or twelve-year-old protagonist, rich themes that have to do with the coming of age time period, etc. etc. etc. But my client hadn’t really thought of the work as MG. Instead, he’d envisioned it as a crossover, perhaps close to THE BOOK THIEF in terms of potential market reach. Basically, he wanted to tell a story and then let the market decide where it fit.

We ended up having a lot of very interesting talks about this idea. Long story short, however, that’s not really how it works. When you’re writing something, you want to have some idea of where it will fit, per my recent “Writing With Market in Mind” post. If you gently leave it up to the publishing gods to decide, you may not get very far. First of all, agents and editors like writers who pitch their projects confidently and know at least a little something about the marketplace.

For all intents and purposes, the project in question seems very MG, even if that was never the client’s conscious intention. And if it walks like a MG, and it quacks like a MG, if my client doesn’t pitch it as a MG, he’s going to get some raised eyebrows. Furthermore, if he doesn’t pitch it as a MG, it may just get slotted into that category by agents and editors alike anyway. If he were to query adult fiction agents with the project, as I’ve described it, I guarantee most would say, “This isn’t my wheelhouse, this sounds like MG. You should be querying children’s book agents.”

You can always say, as my client did, “Well, I sure would like to tap the crossover audience and sell this to children and adults, please and thank you.” Wouldn’t that be nice for everyone? Most people would love a crossover hit like THE BOOK THIEF or THE CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME. Selling the same book to two different markets? Yes, please.

The problem with a crossover is that you can’t aim for one, however. I have said this before and I will say it again (and again and again). The only person to decide that is a publisher, and most won’t take the risk of trying to publish across categories. This strategy is reserved for only a tiny fraction of all books that go to print. And sometimes, a crossover only becomes a crossover when it’s published in one category first, then the other, and it happens to gain traction in both.

What I’m saying is, it’s a lot easier to set some lobster traps than it is to drag the whole of the sea. At least with the former strategy (picking a concrete category), you will probably catch some lobsters. With a wider net, you may catch everything, but there’s a big chance you’ll catch nothing, or a whole lot of garbage.

Many beginning writers think that putting, “This book will appeal to everyone from age 1 to 101!” is a huge selling point. Who wouldn’t want to sell to everyone from 1 to 101? That’s, like, billions of people. Why wouldn’t a publisher want to sell billions of books? Unfortunately, this line of thinking is delusional. Any marketer will tell you that your catchment area is too big. What a one-year-old likes is very different than what a 101-year-old likes and that’s actually a good thing.

So I advised my client to either a) become okay with the idea of pitching his story as a MG, or b) edit the story and weave in several elements that would give it more appeal to the adult fiction marketplace. This isn’t too far-fetched because there are a lot of books set during the “coming of age” period that go on to publish in the adult realm. That 9-12 or 13-18 age range isn’t just for children’s novels. The revision route is obviously the taller mountain to climb, but, if it fits the client’s vision for the book better, then it’s what has to happen.

The jury is still out on what this client will choose to do, but I wanted to bring the situation to everyone’s attention, because it contains some valuable truths about “picking a lane” and thinking about the category of your own work.

A lot of writers hear the well-meaning advice that, in order to break in more easily, they should have some writing clips and credits to their resume. It’s good advice, and I especially don’t want to disenfranchise the many writers who have been actively pursuing this strategy with my answer, because it is a very worthwhile strategy.

In case you haven’t thought about this issue before, I’ll summarize here: When you’re an aspiring writer, you have a lot of ambition to write, but not a lot of platform. People aren’t buying what you want to sell, basically. Or, if they are, they aren’t really paying you for it. You’re probably getting opportunities to showcase your work on blogs and at other web-based venues that don’t have a budget to compensate contributors. Or maybe you start your own blog, like this ol’ hack did! This is how a lot of people get going.

Then you think that there has to be more out there that’s, well, more noteworthy to a potential publishing gatekeeper. So maybe you explore other avenues to showcase your work. Whether it’s in the children’s writing realm, say, Highlights Magazine, or in an unrelated area, like an op-ed for the local newspaper, or a poem in a general fiction literary journal, you start to set your sights higher.

Whether you try to gather clips in print journalism, the literary community, scientific or medical magazines (a lot of writers have done a lot of technical writing for their day jobs), etc., you’re basically writing and racking up pieces that someone else has vetted and decided are good enough to publish.

This all makes a lot of sense, right? If you want to write, write, and maybe the momentum of all your writing will speed up your efforts on the book publishing front. Being published is being published, no matter what you’re publishing. And writing professionals love to see writing credits. Right? Weeeeeeeeeell…

It’s not often that clear-cut. Publishing an op-ed in your local paper in Portland is not the magic ticket to calling attention to yourself with a children’s book editor in New York, unless, of course, your op-ed or Huffpo article causes such a stir that it goes “viral” and attracts a lot of attention or controversy. In fact, under my original name (a much longer version of “Kole”), I published an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, which is a notable newspaper that people have heard of. And I thought, for sure, this was my golden ticket. The day it ran, I waited for the phone to ring. Aaaaand…my mother was very proud of me. Then one man from Idaho took offense at my sense of humor. That’s about it.

The fact of the matter is, if you can say in your query that you’ve published with a top-tier publication that most casual readers have heard of, that’s going to be an amazing feather in your cap. And agents and editors might take notice. But it’s likely not going to get you a book publishing contract.

And outside of that, if you’re publishing on blogs, or in smaller literary magazines, or in venues that have nothing whatsoever to do with publishing novels, then your clips are going to tell a potential agent or editor one positive thing, but one positive thing only: That you’ve hustled a little and know a little bit about the process. And that’s a positive thing, because that might indicate that you’re at least somewhat easy to work with during the publishing process. But it’s not a guarantee of anything.

My main objection to splitting your focus and concentrating on amassing clips if your primary goal is to publish a book can be expressed in this recent post. The truth of the matter is, some journalists spend years trying to crack the New York Times for their own resumes. It’s an entirely new skillset. First, there’s learning how to write well enough that the Times would take interest. Then it’s cultivating contacts and editor relationships that will get you prime consideration. Then it’s learning the culture of the publication (and every publication has one, no matter how small they are) and learning how to work within it successfully. After a lot of effort, you may finally get published in the Times. But then you’re published in the Times, not in the book realm.

What’s missing from this picture of all the effort you’ve put in? Oh yeah, honing your novel craft, which is why you’re doing any of this to begin with. So gathering clips is phenomenal, but it doesn’t help you accomplish your primary goal directly. And there’s no guarantee that it will help you accomplish your primary goal indirectly, either. You may sink a few years into pitching freelance articles to magazines, distract yourself, and maybe emerge with one well-regarded piece in Real Simple…that has nothing to do with your novel.

Is that payoff worth it? Only you can decide. This strategy only seems to work well when you’re a journalist in your day job, and a novelist by night. Then you possess both skillsets already, and you can jump back and forth more easily. Otherwise, it’s like going through all the work and trouble of growing a new arm, just so you can give your primary hands better manicures. It seems like a lot more effort than it’s worth.

Many of you who are familiar with my writing have heard me express surprise and frustration at the idea that so many writers are obsessed with the pitch that the product (in our case, the manuscript) seems almost an afterthought. Back when I would speak at conferences, I would get maybe 8 questions out of ten about the query letter, with only 2 about craft. Once the pitch is over (one page, or about three minutes in a conference session), the burden of proof falls squarely on the product. And in the end, the product is what matters!

But people still love to talk about that pitch. I think I know why. It’s what you present, so IT feels like the “make or break” point, not the manuscript that follows. It’s also shorter and more formulaic, so it’s easier to control. You can’t really control whether someone falls in love with your manuscript right from the get-go: Tastes vary, manuscripts are of various quality, and your style comes into play a lot more. But with the pitch, if you have a great query, it’s pretty easy to feel confident. There are fewer moving parts to gamble with.

So that’s where the attention goes. Good? Bad? I say it’s understandable.

The pitch is what opens the door, so it does deserve its fair share of focus. But once you have someone on the hook, you still have to reel them in, and that’s where all attention goes back to the manuscript. So you can’t escape that nasty product part, no matter how hard you try.

To even get people to look, though, you need the pitch to be solid. The more I think about it, the more I see that a pitch needs to:

- Be specific

- Be targeted (audience-focused)

- Answer the question, “Why does my audience need this?”

The good and bad news is that a pitch can’t change your product. It can spin it, sure, and a certain amount of spin is desirable, but if you aren’t already thinking about these questions as you write your project, your pitch won’t superimpose them onto your manuscript in a satisfying way. You can say that your product is all sorts of things in the pitch, but if that doesn’t come across when someone reads it, the pitch is going to get thrown out as inaccurate. So if you’ve never thought about what your book really is, or who it’s for, or why it’s necessary in a crowded publishing marketplace, you’re likely going to struggle mightily with the query letter, which basically asks you to talk about all of these things.

The worst pitch in the world is pretty much along the following lines:

This is a really great coming of age story about a character who goes through a lot of stuff and comes out the other side. It’s for everyone from zero to 100, and I wrote it because I’ve had this story in my head for thirty years, simply begging to be told, and it wouldn’t let me go until I got it all down on paper.

It’s not specific (every story that involves character change can be seen as a “coming of age”), it spits in the face of the old adage about trying to be everything to everyone and brazenly disregards the reality that there are very specific audiences out in Publishingland, and it doesn’t justify its own existence in the larger scheme of things. You know how baby pictures are always adorable to the parents? And that’s great? But not everyone wants to look at other people’s baby pictures past the first couple unless there’s something personal and notable about them? Do you see where I’m headed with this?

Back to Shark Tank. The entrepreneurs that make it hook the Sharks with a pitch that answers the above questions. What’s the product? It’s not just a doohickey. The world has enough of those. It’s a doohickey that’s for…the kitchen, the garage, taking great baby pictures, whatever. In publishing terms, let’s say it’s a dystopian romance.

It’s not for everyone, because if you say it’s for everyone, the savvy Shark is going to know full well that you can’t market a product to everyone. For exaggeration’s sake, that would cost trillions of dollars and you’d have to get your message to the outer reaches of Mongolia. Not possible, nor desirable, even. Because the savvy Shark knows that 7.9999 billion of our 8 billion marketing recipients are probably not going to like or need whatever the product is. There’s only one thing that’s for everyone, and that’s oxygen. (Except anaerobic bacteria don’t like it. See? You can’t please everyone.) And maybe vanilla ice cream. But are you really going to try going up against the clout of vanilla ice cream?! Everyone is different, and we all like different things. This is GOOD. In publishing terms, our example is a dark YA fantasy for today’s troubled world.

Finally, we get to the big “why.” And this is the hardest question to tackle. I am often left with this idea after I finish reading a manuscript. And? So? Why? Why does this need to be a story? “Well,” the writer stammers, “it’s a story I really want to tell about a kid who goes on an adventure.” So what? Everyone goes on adventures every single day. We all have incredible stories that make up our lives. Why do I need to give you hours of my time and dollars of my paycheck to read your story? (Especially since it’s one you just made up?) Well, that’s where the question of theme comes in. What about your story is going to dovetail with my story and bring about a new or different understanding of the bigger picture? How is it going to elevate my life? In our publishing example, let’s say that heavy identity and survival themes are explored against the backdrop of a troubled world, which uneasily mirrors our own. To think about this as you write, to mention this in the query shows that you’ve seriously thought about the “why” and that your product has a raison d’etre (reason for being, I don’t know how to do the little hat accent on the first “e”).

Let’s tie our doohickey example all together and hit all three points:

The Doohickey 3000 is a revolutionary tool for new and exhausted parents that guarantees you’ll never take a bad baby picture. Baby will be so mesmerized by the Doohickey 3000 that they won’t blink, drool, cry, or vomit, and it will coax a gummy smile out of even the fussiest youngsters. Whether it’s to finally get your family and friends to “like” your damn baby pictures, or to take the world by storm by landing your baby on one of those terrible clickbait viral websites, the Doohickey 3000 will help you foist your bundle of joy on the world with ease!

Now let’s circle back to our publishing example:

DOOHICKEY is a dark YA dystopian romance that pits two teenagers against a scary and uncertain world that closely resembles our own. By deeply exploring themes of identity and survival, it will give contemporary teen readers an outlet to explore some of the fear and uncertainty of growing up in a world where there’s a public shooting every week and we have somehow turned into our own worst enemies.

If you don’t know how to answer some of these questions about your own manuscript, maybe it’s time to go back and really dig into that third question, the “why.” Why are you writing it? Why is it a good project to work on now? Why might the world embrace this story?

“Because I wanna write it, I just wanna,” is fine, and that passion is what’s going to keep you going through revisions, but it’s not enough when you start to think about the reality of publishing, which is that publishers want to put products (books) out that will sell to customers (a reading audience). They don’t just exist to make your childhood dreams come true, or so you can print business cards that say “Author.”

Once you know what it is, who it’s for, and why they’d probably like it, then the pitch becomes very easy to assemble.

I received a question the other day (thanks, Kate!) about author notes in picture book manuscripts. Great stuff. Let me give you some information on the topic so that you can move more confidently forward with your picture book submissions.

First of all, you see author notes more frequently in non-fiction work. After the topic is covered in the manuscript, it’s widely accepted to hear from the author (limited to about a page, with text that’s not too dense). The purpose is to add a few interesting tidbits that maybe didn’t fit into the actual narrative (maybe you’re covering a certain period in history with the text, and want to add some “footnotes” of what we’ve learned about that period since), or to personalize the subject. Authors will often speak to why they gravitated to a particular subject or why they find it particularly fascinating. You shouldn’t style it as a diary entry, but as long as you can keep up the same tone and level of interesting content, you can take a more personal approach. The tone is friendly and engaging.

For non-fiction/fiction hybrid and straight-up fiction manuscripts, where there’s a non-fiction subject but it’s fictionalized or the project deals with a non-fiction principle applied to a more artistic main text, the author note switches function. If your project, is, for example, a fictionalized account of a historical figure or a purely fiction story whose plot has a lot to do with the life-cycle of Monarch butterflies, for example, you want to use the author note as a teaching tool, to provide concrete information. The text is all about Bonnie observing the Monarch life-cycle, but the author note sums it up with additional facts that would’ve weighed down the text itself. The tone is more academic.

So what kind of author note do you have on your hands? Are you “softening” a non-fiction text or are you adding factual scaffolding to a fiction or fictionalized text? For the former, you’ll want to keep your author note brief. If your text is 2,000 words, 250 additional words wouldn’t be uncalled for, or an eighth of your manuscript length. (Do note that non-fiction picture book texts tend to run longer than fiction, because it’s understood that there’s more information to communicate and the audience is on the older end of the spectrum.) If you are working with the former “scaffolding” style of note, 500 additional words, or a quarter of your main text, would be your upper limit.

These are not hard-and-fast guidelines, but more of an exploration of the issue. Use the author note to say enough, but don’t write a second manuscript. If you find there’s a whole lot you want to add in your postscript, maybe there’s a way to revise the main text? Remember, the note shouldn’t do the heavy lifting. The main text has to be the star.

As for mentioning the author note in your submission, that’s easy-peasy lemon-squeezy: “The main text of TITLE is X,000 words, with an author note of X words at the end.” Ta-da!

I’ve discussed picture books primarily in this post, but MG and YA novels also have tons of room for an author note. If, say, your YA is largely inspired by the historical character of Lizzie Borden, feel free to spend even 2,000 words or so on some of the bloody facts of the case, and why your twisted little mind (  ) decided to use it as inspiration. Word count limits apply less to novel author notes, though you still want to keep them engaging and quick.

) decided to use it as inspiration. Word count limits apply less to novel author notes, though you still want to keep them engaging and quick.

I’ve interrupted my own programming, so look for the follow up to my “Product and the Pitch” series next week!

I tell clients all the time that my job is to manage expectations. Part of working with a freelance editor is expecting to be pushed outside of your manuscript comfort zone a little bit. Most writers come to me with the thought, “I am excited by my idea but I know there are several things that aren’t working. I want to learn and grow and make it better.” Maybe that writer has gotten some early feedback from critique partners about things that need tweaking. Or they’ve already done an unsuccessful submission round with agents or editors and they didn’t get the response they expected. Or maybe their manuscript isn’t meeting their own internal expectations and they just don’t know what to do about it. Enter a second pair of eyes: an editor.

A small percentage of writers, however, and I’ve only had this experience twice in my editorial career, are so convinced of the merits of the manuscript that they’re not looking for an editor. They are looking, I’d imagine, to get on the radar of someone even tangentially connected to the industry, and get a booster to the top. Maybe they think I will recommend them personally to agents. Maybe they think I’ll start agenting again myself for the sake of scooping up a hot project. Or maybe they just want the gold star from someone who has made a career of saying, basically, “yes” or “no” to thousands of other writers.

I try very hard to generate constructive, actionable feedback. I’ve never sent a set of notes that says, “This sucks, it’s dead in the water, and you should probably stick with your day job.” One time, at a conference, I met with a writer who told me something shocking. “This,” she said, “is the first manuscript I’ve written in twenty-five years. I had a writing teacher in college tell me I was no good, and it hurt so much that I stopped writing altogether.”

This woman lost twenty-five years of her writing life. She clearly loved doing it, but because one voice (in a presumed position of authority) told her she wasn’t good enough, she gave up on her dream for a quarter of a decade (and almost all of her adult life up until that point). People perceive me as an authority, too. And so I have made it my goal to never wield that power in a way that hurts a writer.

Do I rave about every manuscript unequivocally, then? Absolutely not. Even excellent writers have some blind spots. So whether I’m helping a beginning writer cut fancy “said” synonyms out of their dialogue, or I’m helping an MFA-graduate with beautiful prose work on plot and overall sales hook, I try my best to do it with the dignity and respect that each writer and each manuscript deserves, for where they are in their individual journey.

All that said, I still run into writers who have expectations that perhaps outpace their current manuscripts. Whether those expectations are of the one-in-a-million runaway success, or their shot at being a multimedia mogul, perhaps even in the query letter, I see this happen with writers. They’ve created websites, maybe, or products, or they’ve already self-published. They have a lot to say about various awards they’ve won or endorsements they’ve gotten. There’s little talk about the manuscript, though, as if that was just an afterthought.

This sends a message to me that the writer isn’t as interested in rolling up their sleeves and working on the product itself. To me, everything but the manuscript is just noise. You can send me a t-shirt with your characters on it, or a list of testimonials from school appearances, and all that is fine and good. I’m a driven, type-A personality, too, and I have way more ideas than I have time to make them all a reality. I respect proactive people. But my only concern is the manuscript.

It’s what an agent or editor will respond to. It’s what will stand out among the noise if it’s, indeed, worthwhile. I saw excitement bubbling over for a perfectly lovely client last week, and I wrote to them: “The only way to get someone excited about your work is by presenting good work, and letting it speak for itself.” It’s easy to say but very hard to do. It’s also at the very core of what I do as an editor. Every writer has a different personality, and some are more eager than others. That’s okay. My job, however, is to help put the crucial piece of that manuscript into place, and help writers create good work so that they can then present it. It’s as simple and as difficult as that, but, man, do I love my job.

If you are an illustrator, I highly recommend having a simple portfolio website that you can use to display your work. When you’re querying, instead of attaching images (most editors and agents don’t accept attachments anyway), you can just send a link to your collection. Add new things, change out images in your rotation, and keep it clean, simple, and maintained. That’s about it. And if you’re not tech savvy, you may be able to hire someone via Elance (a freelance marketplace I’ve used to find web designers, or contractors in any arena, in the past) or in your circle of friends to put your image files (scans or digital creations) online. Just make sure that if you use scans, they are of high quality and taken under good lighting that’s true to your intended color scheme.

Two sites that I see a lot of illustrators gravitating to are Wix and SquareSpace. They are built to be user friendly and easy on the wallet. You can use templates provided or get someone to customize your site. These options are modern, work well across multiple platforms, and are easy to link to your other online efforts. I haven’t used either but I’m coming up on a project in my personal life and seriously considering SquareSpace because I like the design and functionality of their sites. I’ve been on WordPress for years and years, so maybe it’s time to try something new, minimal, and graphics-focused!

If all of this is very scary to you, you can just start a free Flickr account and make a gallery of your images. This is the bare minimum, and allows you to host your image and a description (I would opt for one if you can). Send links to the entire gallery in your query so that visitors can click through the whole thing instead of landing on just one image.

Many people overthink this sort of stuff because sometimes computers can be scary and the demands of building a platform seem overwhelming. Don’t let that stop you from putting up a portfolio. Hosting one online has become quite necessary these days, and agents and editors except to see several examples of your work, with different composition, subject matter, tone, palette, etc. (if possible), before they can decide if they’re interested or not.

When I talk about a logline, I mean a quick and effective sales pitch for your story. It is the same as the “elevator pitch” or your snappy “meets” comparison (Harry Potter meets Where the Wild Things Are!). However, not everyone’s book fits the “meets” way of doing this, so they’re left with constructing their own short sentence to encapsulate their work. That’s where things often get hairy.

If you think queries and synopses are hard, loglines are often a whole new world of pain for writers. Boiling down an entire book into four pages? Doable. Into a few paragraphs? Questionable. Into a sentence or two?! Impossible.

Or not. The first secret to crafting a good logline is that you should probably stop freaking out about it. If you can get it, good. If not, you can still pitch an agent or editor with a query or a one-minute summation of your story at a conference or if you do happen to be stuck with them in an elevator. Nailing it in one sentence is more of an exercise for you than a requirement of getting published.

That said, my surefire way to think about loglines is as follows:

1) Connect your character to your audience

2) Connect your plot to the market

Let’s examine this. First, begin your logline with your character and their main struggle. This is a way of getting your audience on board. For example, with Hunger Games, Katniss would be “A girl hell-bent on survival…” or “A girl who volunteers herself to save those she loves…”

Now let’s bring plot into it. When you pitch your plot, you always want to be thinking about where it fits in the marketplace. At the time that the first Hunger Games was published, dystopian fiction was white hot as a genre. That’s not so much the case anymore, but if I had been pitching this story at that time, I would’ve definitely capitalized on the sinister dystopian world building. To connect the plot to the market, I would’ve said something like, “…in a world where children fight to the death to keep the population under the control of a cruel government.” This says to the book or film agent, “Dystopian! Right here! Get your dystopian!”

So to put it together, “A girl volunteers herself to save those she loves in a world where children fight to the death to keep the population under the control of a cruel government.” That’s a bit long, and not necessarily elegant, but it definitely hits all of the high notes of the market at that time, while also appealing emotionally to the audience. (Volunteering for a “fight to the death” contest is a really ballsy thing to do, so we automatically want to learn more.)

Notice that here, even the character part involves plot (it focuses on Katniss volunteering).

If I’m working on a contemporary realistic novel, the “plot to market” part is less salient because we’re not exactly within the confines of any buzzy genre. That’s fine, too. You should probably be aware early on whether you’re writing a more character-driven or plot-driven story. The Hunger Games nails some strong character work, but I would argue that it’s primarily plot-driven, or “high concept.” With character-driven books, the former part of the logline construction becomes more important. Let’s look at Sara Zarr’s excellent Story of a Girl. The title is pretty indicative of the contents. It’s literally the story of a girl, and the girl is more important than necessarily each plot point that happens to her.

With character-driven, I’d spend most of my time connecting character to audience. I’d say, for example, “A girl from a small town struggles with the gossips around her who refuse to forgive her past mistakes…” This is the girl’s situation for most of the book, and part of her biggest “pain point” as a person. Then I’ll need to indicate the rest of the plot with something like “…must step out from the shadows of her reputation and find out who she really is.”

Notice that here, even the plot part involves character (it focuses on the more subtle work of figuring herself out rather than, say, battling to the death).

Both are solid loglines because both communicate the core of the story and the emphasis of the book (plot-driven vs. character-driven, genre-focused vs. realistic). Try this two-step exercise with your own WIP.

You know I’m busy at work when instead of going through art samples with my morning coffee, they pile up on my desk. Today, I finally took lunch to sort through a few. Check out some exciting new finds that came in lately!

Casey Uhelski / For pet lovers (like me!), this SCAD grad has mastered the expressions of adorable dogs, cats and bunnies.

Victoria Jamieson / Victoria’s anthropomorphic characters have landed her a two-book gig with Dial (part of the Penguin family) in 2012/2013. In the meantime, I think her revisiting of Ramona Quimby is spot-on.

David C. Gardiner / This image might suggest that David and I are cut from the same cloth, stylistically, but his Flying Dog Studio also produces everything from fairly realistic older characters to animations.

Caitlin B. Alexander / This Austin-based illustrator’s folksy-yet-modern style looks mostly editorial, for now… but wouldn’t it make a charming children’s book?

Veronica Chen / I was intrigued by her intricate black-and-white patternwork, but her color piece Chameleon City just begs for a story to be told.

Jillian Nickell / This quirky, vintage-inspired vignette was fascinating enough to lead me to her website, where there’s a great series of pieces based on The Borrowers, and more. I can picture her style being perfect in the right book for older readers!

Filed under:

from the slush pile,

illustration sensations Tagged:

illustration,

new artists,

postcards,

Display Comments

Today was a more wackadoo day in illustrator submissions than usual, so I thought I’d give myself a pick-me-up by highlighting three great illustrators who draw some super-cute animals. Enjoy!

1. Charrow / My first favorite recent find is Charrow, whose quirky illustrations exude a playful spirit and sense of humor. Her light watercolor and drawing technique feels breezy, like she just jotted down some animals, and they happen to be hilariously adorable. She’s also a frequent contributor to They Draw and Cook. Her Etsy shop is down at the moment, but when I checked it out a few weeks ago, it was easily my favorite part of her portfolio… be sure to check back for it soon!

2. Stephanie Graegin / Probably my all-time favorite illustrator submission ever is a little “mini portfolio” booklet from Stephanie Graegin. Her Renata Liwska-style woodland creatures, accented by limited color and unlimited sweetness, had both design and editorial drooling. Crossing my fingers that I see a book with her name on it soon!

3. Lizzy Hallman / If illustrator David Catrow’s art proves anything, it’s that there’s a place in this business for a little ugly-cute. And if my love of french bulldogs proves anything, it’s that I will always get behind ugly-cute! Hallman’s characters may have wonky eyeballs, but they make their expressions unique and humorous. And her color treatment? 100% sweet!

Filed under:

from the slush pile,

illustration sensations Tagged:

animals,

children's book,

drawing,

By:

Annie Beth Ericsson,

on 10/28/2010

Blog:

Walking In Public

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book design,

typefaces,

slush,

book covers,

design finds,

illustration sensations,

from the slush pile,

hand-made,

hand-drawn type,

Add a tag

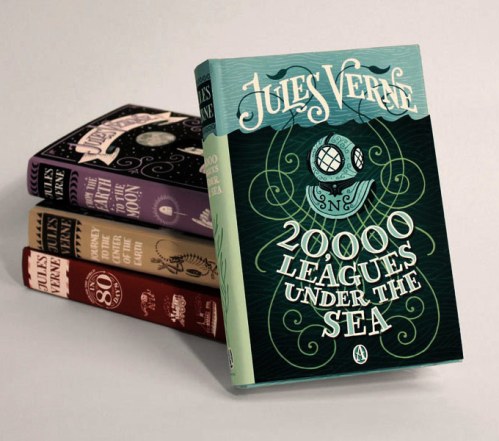

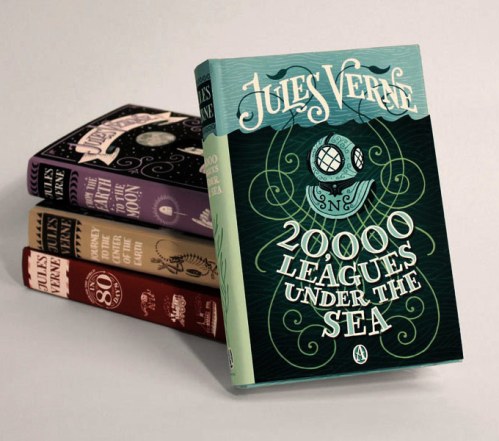

While going through the slush mail today, I came across a pair of standout illustrators in a pile of recent UArts grads. Jim Tierney and Sara Wood, a young Brooklyn couple, have a fantastic approach to book cover design. Their masterful combination of type, hand-lettering and drawing makes both of their portfolios equally impressive.

Check out Sara’s D. H. Lawrence book cover series, and Jim’s interactive Jules Verne thesis (there’s a

video too!).

I put the cards up on the “Wall Of Stuff I Like” in my cube, right next to our other favorite hand-drawn type designer,

Kristine Lombardi. Lombardi’s cards have been up on our wall for ages. While her cards have more of a feminine, fashion style (although I do like her

Kids page!), they are the first thing that designers walking by are ALWAYS drawn to. Check out a great interview (including the below image of her promo card)

here.

These designers got me to thinking: where’s the place for hand-lettered type in children’s books? Before the age of thousands of freebie fonts on the internet (hey, it wasn’t that long ago!), hand-lettered display type was commissioned for book covers all the time. I recently worked on the anniversary edition for Jacqueline Woodson’s

The Other Side, and I was so impressed to discover that the handsome title was calligraphed by the original in-house designer.

And while I’m sure it took a lot more effort than downloading a font, there’s something careful, purposeful and yet whimsical to hand-drawn type. So it’s no surprise that it is experiencing a rebirth of magnificently hip proportions. Now, type everywhere looks like this:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 8/24/2010

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

movie news,

slush,

Anne of Green Gables,

Nathan Bransford,

Henry Reed,

Megan McDonald,

Katie Davis,

Wendy Mass,

Trixie Belden,

Fusenews,

3 Investigators,

bras (tee hee!),

comic book blogs,

Danny Dunn,

Richard and Florence Atwater,

Add a tag

It's the bellbottoms on the hippy dippy minstrel that I love.

- Comic book bloggers and children’s literature bloggers are two sides of the same coin. Our interests often run parallel. The degree to which the academic world regards us is fairly similar (though admittedly we get to have Norton Anthologies while they are sorely lacking any such distinction). I don’t read my comic book blogs as frequently as I might, but once in a while the resident husband will draw my attention to something particularly toothsome. Such a case was this series on Comic Book Resources. A fellow by the name of Greg Hatcher makes a tour of the countryside each year, finding small towns with even smaller bookshops and thrift shops. This year his has posted his finds and the children’s literature goodies are frequent. In part one he pays homage to a surprise discovery of Kieran Scott’s Geek Magnet and shows the sad state of Sacagawea-related children’s literature in gift shops today (though I sure hope the Lewis & Clark gift shop also has the wherewithal to carry Joseph Bruchac’s Sacajawea: The Story of Bird Woman and the Lewis and Clark). In part two Greg discovers the oddly comic-less Janet Townsend novel The Comic Book Mystery, finds the name Franklin Dixon on a book that ISN’T a Hardy Boys novel, and waxes eloquent on the career of illustrator Kurt Wiese. In part three he locates some very rare and pristine Trixie Belden novels (which I adored as a kid). And finally, in part four he introduces us to the Danny Dunn series, shows us a hitherto unknown Three Investigators cover, and discusses Henry Reed (with illustrations by Robert McCloskey, of course). If you enjoy bookscouting in any way, these posts are a joy. Take a half an hour out of your day to go through them. Greg writes with an easy care that I envy and hope to emulate. Plus I loved the idea of giving photographs inserted into posts colored notations the way he does. I’ve already started to try it myself. Thanks to Matt (who, I see, recently credited Better Off Ted, for which I am grateful) for the links.

- I sort of view agent Nathan Bransford with the same wary respect I once bestowed upon a toucan I found in the London department store Harrods. I’m grateful that he’s there and I can’t look away, but there’s something unnerving about running across him. And now he appears to have a book coming out with Dial in 2011, which is nice except that I keep misreading the title as Jacob Wonderbra and the Cosmic Space Kapow. For the record, I would give a whole lot of money to any author willing to name their titular character (childish giggle) after a bra, a girdle, or even a good old-fashioned garter. Okay . . . why am I talking about Nathan Bransford again? Oh righ

by Jane

Recently the

Wall Street Journal ran

an article titled "The Death of the Slush Pile." How incredibly sad, I thought.

One of my very first jobs in publishing was managing the slush pile at Bantam Books. I didn’t do much; all I was told to do was to log the manuscripts in, put them on a shelf and then two weeks later, reject them after nobody had looked at them. I hated doing it--those writers had worked so hard and yet, even all those years ago, there was nobody to read their work.

From that time on, I have had both respect and curiosity for “slush.” Even today, in a very difficult publishing market, I firmly believe that the slush pile can hold “buried treasure.”

And aside from the very public examples cited in the

WSJ piece, we at DGLM have proven that there are wonderful projects to be found if one is patient and persistent enough to look.

Jim McCarthy discovered Carrie Ryan in the slush pile. She wrote

The Forest of Hands and Teeth,

which Jim sent out on a Friday and sold the following Monday. He also found Victoria Laurie, one of his first clients in slush. Jim has sold 18 of her books in the last six years.

Mike Bourret found three of his biggest clients in slush: Lisa McMann, author of

Fade and

Wake, among others; Heather Brewer whose first book among many, was

Eighth Grade Bites; and Sara Zarr whose

Story of a Girl was a National Book Award finalist.

Our very own Mary Doria Russell lay in a colleague’s slush pile for almost a year and when he didn’t respond, her first novel,

The Sparrow, was passed along to me--and the rest is history.

So, no matter how busy I am, I have not forsaken the slush pile--and, hopefully, even in difficult times, I never will.

Never do this:

Dear Editor,

I recently mailed you a query letter regarding an MS I had completed _______________, for which I enclosed a SASE. It has just come to my attention that my secretary (me) forgot to put a stamp on the camp. Please find enclosed appropriate postage.

And enclosed is a stamp.

Um. That’s very nice. But I am not going to label this stamp with the MS title and leave it on my desk until the MS shows up. Especially because there is a good chance that I already read the query letter, found the stampless SASE and trashed it.

If you realize you’ve done something like this, don’t send me postage. Just resubmit the MS.

Oh well. Free stamp for me, I guess.

Here’s a tip: don’t write a message, write a story.

I can’t even begin to tell you how many queries I read that say something like “this book will teach children about the importance and value of sharing” or “the importance of multiculturalism will come clear in this picture book” or “each book in my series teaches another valuable lesson like if at first you don’t succeed try try again.”

Seriously, when I read that, I mentally recoil and have absolutely no interest in your story whatsoever.

I don’t want a message. I don’t want a picture book which will relay a nice idea. I don't want a preachy moralistic tale.

I want a great story. I want a funny text. I want something sweet that will bring tears to my eyes.

I want a story that moves me.

If there’s a message buried somewhere in there, well that’s great. There’s a message buried somewhere in every story we write and publish, because that’s why we write. We write to tell stories, to get ideas across.

If you are a passionate, dedicated writer, I suspect that there is a message of some sort in your work.

But don’t tell me about it. Don’t set out to write a story about multiculturalism or sharing or being nice to others that is really a thinly veiled vehicle for a cause. Don’t send it to me, and don’t write it, and most importantly of all, don’t tell me about it.

I’m not looking to publish causes and messages. I’m looking to publish great stories.

Tell me about the story.

I’m having a bit of a slow day, so I’m attacking the ginourmous pile of slush next to my desk. Here are some reactions to actual things in slush letters.

Things not to put in your query:

1. The line “give it a read, and I think we’ll do business.” I can’t speak for all editors everywhere, but I hate smarmy, self-assured ego. Self-confidence, yes. Smarmy ego, no.

2. The title page, table of contents, authors note, and first chapter of your novel. Okay, maybe that’s what some houses submissions guidelines request. Ours requests query letters. Other imprints here request the first ten pages, or something like that. It doesn’t take a brain to figure out that the title page, table of contents, and author’s note are not what is going to make me want your novel (see above, under “smarmy ego.” (Not that it matters, because this guy didn’t bother including an SASE, anyway. Trash!)

3. The line “I had a dream and upon awakening I wrote this story.” Doesn’t endear me to your work, and I really don’t care what the inspiration is for your story about ducklings.

4. In the vein of what I mentioned before, anything from a so-called agent that ends up in the slush pile. If it’s agented, it should go directly into the hands of an editor. When I get these, I always want to contact the author directly and tell him to drop the agent like a red-hot coal and find a real agent. This sort of agent is worse than not having any agent at all. (Something I want to talk about more, but for another time.)

5. A picture book MS that is written “with illustrations in mind (picture.)” And that means that after every line of text is another “(picture.)” Yes, I know that picture books are illustrated. Thanks for enlightening me on that one.

6. The name of an editor who no longer works at my company on your query. This editor left months and months ago. There are still queries arriving for her in our mail. It’s not like she would read them anyway, but still. If you’ve taken the time and energy to look up an editor’s name and title and address, maybe you should keep track of the fact that they’re no longer there. These things aren’t secrets. Lots of websites post changes in publishing personnel. I know, it’s not really a big deal. But it’s starting to get on my nerves. Do your damned homework.

7. Your SASE should be a normal, letter-sized envelope. The kind that an 8x11 piece of paper fits in when folded neatly into three. You know what? You want to use a larger envelope? Fine, that’s cool too. But don’t go smaller on me. I don’t get any kicks out of folding your rejection letter like it’s origami trying to get it to fit. If I have too much trouble getting your rejection into the envelope and closing it, I am going to toss the letter and the envelope both.

8. The line “books for young children should be extremely short-lived on shelves. A pending patent should alleviate that.” Seriously, I don’t know what that means, but I know that it means that any writer who wants their books to have a short shelf-life needs to find a new goal. Do you know what it means? What is she thinking? I honestly do not understand.

More as it comes.

*Note: Details have been changed, but the basic thought behind these lines are all true.

I honestly never thought that this would be advice that I would give, but after slush letter #5 that made this mistake, I feel that I ought to bring it to your attention.

Writers. When you include your SASEs in your query letters, do us both a favor.

Address it to yourself.

Not to us.

I don’t need to get the rejection letter than I sent you.

You people think I’m kidding. I’m not kidding. This is the fifth SASE I’ve gotten addressed to the publishing house, listing the person’s own address as the return address.

Don’t do it.

You know what's funny? When I read writer's boards like Verla Kay, and writers say "You know, my unagented manuscript's been with the publisher for 7 months now. I think it's time I sent them a status check postcard to find out what's going on."

I'll tell you what's going on, writers. Your manuscript is sitting in a big pile next to my desk. Probably close to the bottom of the pile. Unfortunately, I haven't had the time to get to it yet. Fortunately, it's summer and we're getting an intern and maybe she'll get to it. Hope springs eternal, etc.

But when I get your postcard, asking about the status of your novel, do you really think I am going to go digging to locate yours?

(Answer: I am not.)

The only thing the status postcard accomplishes is that it makes me feel a little guilty. But the giant heaping pile of slush hanging out next to my desk makes me feel guilty all the time anyway, so the extra little bit of guilt isn't going to move mountains or anything.

Sorry. I know it's not what you want to hear. I'm trying, I swear!

A tip for writers:

If you submit a query letter to the slush pile, and you are lucky enough to get a response requesting that you send the full manuscript, this is what you will do, if you are smart:

Include a copy of the original query. Also nice, though not necessary, is to include a copy of the letter/postcard requesting the manuscript.

Because the world of publishing can be a shady place, my friends. Sometimes someone thinks they’re clever and send in a full manuscript and writes “requested material” on the envelope, and thinks that’s going to get it noticed better.

What really happens is that the editor it’s addressed to looks at it, doesn’t recall requesting it, and tosses it on the slush pile.

Sometimes we don’t remember what we requested. Like if a slush query looked intriguing, and we sent out a request for more, and it comes a few months later.

So include the original query, so that we can see clearly that you are not a shady writer trying to get ahead, but rather a legitimate writer with good stuff.

Here’s what I don’t understand.

If you’re going to go through all the trouble of looking up a publishing house’s address online, why won’t you go a step further and find out what the proper protocol is for sending queries?

And okay, maybe you’re a lazy bum and you like me to do your work for you (by sending you a copy of our submissions guidelines, not even a rejection letter.) But at least if you know enough about publishing houses to send your MS, you have the sense to include an SASE?

Seriously, people. If you’re eleven years old and your letter is adorable, maybe maybe maybe I’ll forgive this trespass and send you back your letter with a firm note indicating that you should include one next time. But if you’re a grown-up? No. I don’t care how lovely your story is. It goes in the trash, and you’re not hearing back from me in this lifetime.

Hi aspiring author,

Look, I know you sent in your query letter to us a million billion years ago. I know it is frustrating for you to have to wait. It is frustrating for me, too. Look, there are two piles next to my desk that are almost as high as my desk is, filled with slush. It was that way when I got there. I want nothing more (okay, I want a lot of things more, but I want this a lot) to have the chance to devote a couple of hours to reading through your hopes and dreams and giving you people some answers.

In fact, I feel a little bit guilty every time I sit down at my desk.

But I don't do anything about it. And you know why? Because I am busy. I am really, really, really busy working on books we've already acquired, books we're already publishing. I am really busy, and the editors I work for are even busier. I barely have time to read the agented submissions. That's what my commute is for. And so the pile keeps growing, a few more envelopes every day.

I try. I make a point of reading and responding to at least two pieces of slush a day. It isn't much, but at least it's something. At least it's two more people who aren't wondering any more.

So I am sorry. I do my best, but that's about all I can do.

So don't be annoying, aspiring novelist. Don't send me a fax that says, "from one human being to another, please tell me what the status of my query is." Because you know what the status of your query is? Buried under five hundred other queries, that's what. I'm sorry you're antsy. I'm sorry it's taken so long. Really, I am.

But you know what else? There's freaking nothing I can do about it right now.

So stop whining.

Love,

The Kidlitjunkie

.jpg?picon=380)

By:

Mark,

on 4/1/2007

Blog:

Just One More Book Children's Book Podcast

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Interviews,

childrens books,

Another Season,

Good Night Pillow Fight,

Hey Batta Batta Swing,

New York Yankees,

Sally Cook,

interview,

Podcast,

Add a tag

Mark speaks with author Sally Cook about deciding to be an author while in the second grade, the magic of books and the connections they make between authors and readers, and discovering the lighter side of baseball in her picture book Hey Batta Batta Swing! – 1000 copies of which will be distributed as part of the New York Yankees’ opening day dinner on April 2, 2007.

Mark speaks with author Sally Cook about deciding to be an author while in the second grade, the magic of books and the connections they make between authors and readers, and discovering the lighter side of baseball in her picture book Hey Batta Batta Swing! – 1000 copies of which will be distributed as part of the New York Yankees’ opening day dinner on April 2, 2007.

Other books mentioned:

Participate in the conversation by leaving a comment on this interview, or send an email to [email protected].

Photo: Pippin Properties, Inc.

Tags:

Another Season,

childrens books,

Good Night Pillow Fight,

Hey Batta Batta Swing,

interview,

New York Yankees,

Podcast,

Sally CookAnother Season,

childrens books,

Good Night Pillow Fight,

Hey Batta Batta Swing,

interview,

New York Yankees,

Podcast,

Sally Cook

) decided to use it as inspiration. Word count limits apply less to novel author notes, though you still want to keep them engaging and quick.

) decided to use it as inspiration. Word count limits apply less to novel author notes, though you still want to keep them engaging and quick.

Mark speaks with author

Mark speaks with author

Whoa. I love Jillian Nickell’s illustration there. So cool!