new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: dictionaries, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 311

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: dictionaries in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Word of the Year season closed this weekend with the annual meeting of the American Dialect Society. As usual, major news stories dominated selections, but there has been a notable uptick in social media-related choices. It is interesting to note how hashtags are becoming more prevalent with #IndyRef as a common runner-up, and #dirtypolitics and #blacklivesmatter winning the title.

In the English-speaking world:

- Oxford Dictionaries selected ‘vape’, an abbreviation of vapour or vaporize, given its increase usage with the rise in electronic cigarettes.

- Merriam Webster selected ‘culture’, based on an increase in look-ups.

- Collins selected ‘photobomb’, made famous by monkeys and celebrities.

- The Australian National Dictionary Center (ANDC) selected ‘shirtfront’, meaning ‘in figurative use, to challenge or confront a person’.

- Dictionary.com selected ‘exposure’, noting its relationships to major news stories this year surrounding Ebola, hacking, and Ferguson.

- Cambridge Dictionaries noted several words that demonstrated a surge in look-ups including ‘devolution’, ‘cleavage’, and ‘asphyxiate’.

- Chambers Dictionary selected ‘overshare’: “beautifully British” with “a hint of understatement”.

- Geoff Nunberg selected ‘God View’, the term which Uber uses for their internal map of cars and customers.

- Ben Schott at The Takeaway listed several of the worst words of 2014.

- Dennis Baron selected ‘torture’: “it’s the epitome of what went wrong, not just with counterterrorism, but with everything.” He has already selected ‘autocorrect’ as 2015’s Word of the Year.

- Grant Barrett noted several buzzwords of 2014, including ‘basic’, ‘columbusing’, and ‘flee’.

- Gretchen McCulloch at Slate’s Lexicon Valley made an argument for emoticon of the year.

- And in a related note, Global Language Monitor selected the heart-shaped emoji.

- Public Address (of New Zealand) selected #dirtypolitics.

- National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) of the Philippines selected ‘selfie’ of Word of the Year, chosen among the 13 words submitted during the Sawikaan 2014.

- Nancy Friedman selected ‘Ebola’ (and see her full list of ADS submissions and notable words).

- Ben Zimmer spoke to NPR about some finalists, including ‘die-in’ and ‘platisher’.

- Lynne Murphy selected four UK-to-US and US-to-UK words of the year: ‘gap year’, ‘dodgy’, ‘bake-off’, and ‘awesome’.

- Grammar Girl selected ‘adulting’.

- Hugo used Twitter bots to find some of the top words of 2014.

- Wordnik has a list of 2014 nominations.

- Lake Superior State University released their annual ‘banishment’ list, including ‘bae’, ‘polar vortex’, ‘hack’, ‘skill set’, and ‘swag’.

- Wordspy selected ‘JOMO’ (joy of missing out).

- Baby Name Wizard slected ‘Adele Dazeem’ as Name of the Year. (Hat tip: Nancy Friedman)

- The American Name Society selected ‘Ferguson’ as Name of the Year.

- The American Dialect Society selected #BlackLivesMatter, also the winner of their new hashtag category, reflecting events in Ferguson and around the United States this year.

Around the globe:

- Festival XYZ selected ‘médicalmant’ (a relaxant drug) and ‘casse-crotte’ (bad meal with a cheap drink) as mots nouveau pour 2014. (France)

- The Festival du mot selected ‘transition’ [jury choice] and ‘selfie’ [public choice] for Mots de l’année. (France)

- ‘Zei’ (税) is Kanji (Japanese character) of the year (poll sponsored by the Japanese Kanji Proficiency Society). It means ‘tax'; a proposed sales tax has been in the news in Japan throughout the year.

- The Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache (German Language Society) selected ‘Lichtgrenze’ (border of light), in reference to the celebrations surrounding the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

- ‘Fremmedkriger’ (foreign fighter) was selected by Språkrådet (Norwegian Language Council).

- Genootschap Onze Taal (Dutch language association) and listeners of De Taalstaat (The Language State) voted for ‘Rampvlucht’ (disaster flight), in reference to MH17 and several other air disasters this past year.

- The Van Dale Dictionary selected ‘dagobertducktaks’ (a tax for the rich) as the Dutch Word of the Year. It’s named after Dagobert — better known as Scrooge McDuck in English!

- Van Dale is also behind the selection of ‘flitsmarathon’ for Flemish Word of the Year: “an extensive operation (marathon) of speed checks (flitsen) carried out by police”. Viewers of the Belgian children’s television network Ketnet selected ‘OMG’.

- Listeners of the Danish radio programme The Language Laboratory voted the app name ‘MobilePay’ as Word of the Year.

- Porto Editora selected ‘corrupção’ (the act of becoming corrupt) as Palavra do Ano 2014 through a vote on the Infopédia.pt site. There have been a number of prominent corruption cases in Portugal this past year.

- Fundéu BBVA (la Fundación del Español Urgente) selected ‘selfi’ (selfie) as palabra del año. (Spain)

- ‘Selfie’ is the Zingarelli’s selection for le parole dell’anno 2014. (Italy)

- ‘Fǎ’ (法), meaning law, was selected as Chinese character and ‘anti-corruption’ was selected as Chinese word in a popular poll conducted by the Chinese National Language Monitoring and Research Center and the Commercial Press.

- The readers of Lianhe Zaobao in Singapore selected 乱 (disorder or chaos) as the Chinese character of 2014. People overseas could also vote through Zaobao.com.

- Språkrådet (Swedish Language Council) released a list of 40 new words.

- Chinese character of the year in Malaysia is háng (航), meaning aviation, organized by Malaysian Chinese Association and the Malaysian Chinese Cultural Centre.

- In Taiwan, United Daily Newspaper organized a reader poll that selected 黑, meaning ‘dark’, following media coverage of the ‘dark side’ of industry, politics, etc.

Are there any words of the year that I missed? Any translations that can be improved? Please leave a comment below.

The post Words of 2014 Round-up appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 3/9/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

History,

Language,

bible,

dictionaries,

America,

British,

oxford english dictionary,

supreme court,

scripture,

oxford dictionaries,

united states constitution,

Oxford Dictionaries Online,

oxfordwords blog,

dictionaries in law,

lynne murphy,

lynneguist,

Add a tag

By Lynne Murphy

For 20 years, 14 of those in England, I’ve been giving lectures about the social power afforded to dictionaries, exhorting my students to discard the belief that dictionaries are infallible authorities. The students laugh at my stories about nuns who told me that ain’t couldn’t be a word because it wasn’t in the (school) dictionary and about people who talk about the Dictionary in the same way that they talk about the Bible. But after a while I realized that nearly all the examples in the lecture were, like me, American. At first, I could use the excuse that I’d not been in the UK long enough to encounter good examples of dictionary jingoism. But British examples did not present themselves over the next decade, while American ones kept streaming in. Rather than laughing with recognition, were my students simply laughing with amusement at my ridiculous teachers? Is the notion of dictionary-as-Bible less compelling in a culture where only about 17% of the population consider religion to be important to their lives? (Compare the United States, where 3 in 10 people believe that the Bible provides literal truth.) I’ve started to wonder: how different are British and American attitudes toward dictionaries, and to what extent can those differences be attributed to the two nations’ relationships with the written word?

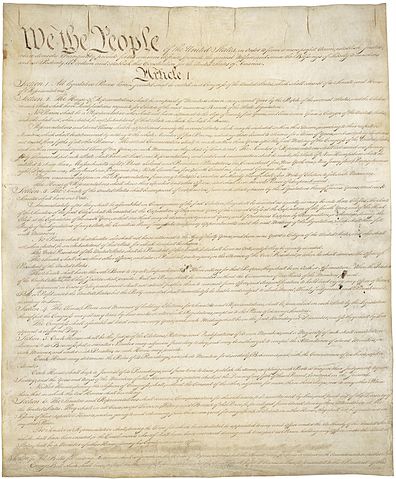

Our constitutions are a case in point. The United States Constitution is a written document that is extremely difficult to change; the most recent amendment took 202 years to ratify. We didn’t inherit this from the British, whose constitution is uncodified — it’s an aggregation of acts, treaties, and tradition. If you want to freak an American out, tell them that you live in a country where ‘[n]o Act of Parliament can be unconstitutional, for the law of the land knows not the word or the idea’. Americans are generally satisfied that their constitution — which is just about seven times longer than this blog post — is as relevant today as it was when first drafted and last amended. We like it so much that a holiday to celebrate it was instituted in 2004.

Dictionaries and the law

But with such importance placed on the written word of law comes the problem of how to interpret those words. And for a culture where the best word is the written word, a written authority on how to interpret words is sought. Between 2000 and 2010, 295 dictionary definitions were cited in 225 US Supreme Court opinions. In contrast, I could find only four UK Supreme court decisions between 2009 and now that mention dictionaries. American judicial reliance on dictionaries leaves lexicographers and law scholars uneasy; most dictionaries aim to describe common usage, rather than prescribe the best interpretation for a word. Furthermore, dictionaries differ; something as slight as the presence or absence of a the or a usually might have a great impact on a literalist’s interpretation of a law. And yet US Supreme Court dictionary citation has risen by about ten times since the 1960s.

No particular dictionary is America’s Bible—but that doesn’t stop the worship of dictionaries, just as the existence of many Bible translations hasn’t stopped people citing scripture in English. The name Webster is not trademarked, and so several publishers use it on their dictionary titles because of its traditional authority. When asked last summer how a single man, Noah Webster, could have such a profound effect on American English, I missed the chance to say: it wasn’t the man; it was the books — the written word. His “Blue-Backed Speller”, a textbook used in American schools for over 100 years, has been called ‘a secular catechism to the nation-state’. At a time when much was unsure, Webster provided standards (not all of which, it must be said, were accepted) for the new English of a new nation.

American dictionaries, regardless of publisher, have continued in that vein. British lexicography from Johnson’s dictionary to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has excelled in recording literary language from a historical viewpoint. In more recent decades British lexicography has taken a more international perspective with serious innovations and industry in dictionaries for learners. American lexicographical innovation, in contrast, has largely been in making dictionaries more user-friendly for the average native speaker.

The Oxford English Dictionary, courtesy of Oxford Dictionaries. Do not use without permission.

Local attitudes: marketing dictionaries

By and large, lexicographers on either side of the Atlantic are lovely people who want to describe the language in a way that’s useful to their readers. But a look at the way dictionaries are marketed belies their local histories, the local attitudes toward dictionaries, and assumptions about who is using them. One big general-purpose British dictionary’s cover tells us it is ‘The Language Lover’s Dictionary’. Another is ‘The unrivalled dictionary for word lovers’.

Now compare some hefty American dictionaries, whose covers advertise ‘expert guidance on correct usage’ and ‘The Clearest Advice on Avoiding Offensive Language; The Best Guidance on Grammar and Usage’. One has a badge telling us it is ‘The Official Dictionary of the ASSOCIATED PRESS’. Not one of the British dictionaries comes close to such claims of authority. (The closest is the Oxford tagline ‘The world’s most trusted dictionaries’, which doesn’t make claims about what the dictionary does, but about how it is received.) None of the American dictionary marketers talk about loving words. They think you’re unsure about language and want some help. There may be a story to tell here about social class and dictionaries in the two countries, with the American publishers marketing to the aspirational, and the British ones to the arrived. And maybe it’s aspirationalism and the attendant insecurity that goes with it that makes America the land of the codified rule, the codified meaning. By putting rules and meanings onto paper, we make them available to all. As an American, I kind of like that. As a lexicographer, it worries me that dictionary users don’t always recognize that English is just too big and messy for a dictionary to pin down.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Lynne Murphy, Reader in Linguistics at the University of Sussex, researches word meaning and use, with special emphasis on antonyms. She blogs at Separated by a Common Language and is on Twitter at @lynneguist.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How do British and American attitudes to dictionaries differ? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/20/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

word origins,

etymology,

rowan,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

aroint,

rauntree,

‘aroint,

language,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Dozens of words have not been forgotten only because Shakespeare used them. Scotch (as in scotch the snake), bare bodkin, and dozens of others would have taken their quietus and slept peacefully in the majestic graveyard of the Oxford English Dictionary but for their appearance in Shakespeare’s plays. Aroint would certainly have been unknown but for its appearance in Macbeth and King Lear. From the speech of the first witch (Macbeth III, opening scene): “A sailor’s wife had chestnuts in her lap, / And munch’d and munch’d and munch’d.—‘Give me,’ quoth I: / ‘Aroint thee, witch!’ the rump-fed ronyon cries.” And in King Lear Edgar, pretending to be mad (III. 4, 129), also says “Aroint thee.”

The origin of aroint has been the object of an intense search. In 1874 Horace H. Furness, the editor of the variorum edition of Shakespeare, knew almost everything said about the word, but he offered a dispassionate survey of opinions without comments. Very long ago, in Cheshire, rynt, roynt, and runt were recorded. Milkmaids in those quarters would say “rynt thee to a cow, when she is milked, to bid her get out of the way.” The phrase meant “stand off.” “To this the cow is so well used that even the word is sufficient.” Rynt you, witch as part of the proverbial saying rynt you, witch, said Besse Locket to her mother turned up in a provincial dictionary published in 1674, approximately sixty years after Macbeth and King >Lear were written. The lady whom Robert Nares, the author of an 1822 glossary of obscure words, consulted added: “…the cow being in this instance more learned than the commentators on Shakespeare.” The taunt missed its target: philologists are not cows, and neither the lady nor the milch cows elucidated the word’s origin. (In my experience, no one understands the word milch, and this is why I have used it here.)

The fanciful derivation of aroint as a compound from some verb for “go” and a cognate of (be)hind does not merit attention. The familiar dialectal pronunciation of jint for joint suggests that the etymological vowel in the verb rynt was oi, not i. Old English had the verb ryman “to make room,” and Skeat derived aroint from the phrase rime ta (ta = thee), imperative, “which must necessarily become rine ta (if the i be long).” I am not sure why the change was necessary, but Skeat sometimes struck with excessive force. Anyway, he reasoned along the same lines as most of his predecessors and followers, who thought that aroint meant ‘begone’. A similar idea can be observed in several attempts to find a Romance etymon of aroint.

Horne Tooke, famous, among other things, for a two-volume book EPEA PTEROENTA, Or, The Diversions of Purley (1798-1805), traced Shakespeare’s word to “ronger, rogner, royner; whence also aroynt… is a separation or discontinuity of the skin or flesh by a gnawing, eating forward, malady” (compare Italian rogna “scabies, mange” and ronyon in Macbeth, above). He obviously glossed aroint as “to be separated” and found several supporters. Other early candidates for the etymon known to me (for nearly all of which I am indebted to Furness’s notes on Macbeth and King Lear) are French arry-avant “away there, ho!”, éreinte-toi “break thy back or reins” (used as an imprecation), Latin dii te averruncent “may the devils take thee,” and Italian arranca (the imperative of arrancare “plod along, trudge”). A strong case has been made for aroint being an expected phonetic variant of anoint or acquiring in some contexts the figurative sense “thrash” (the latter derivation was defended by George Hempl, a distinguished American philologist), or because it “conveys a sense very consistent with the common account of witches, who are related to perform many supernatural acts by means of unguents.” Finally, Thomas Hearne’s Ectypa Varia ad Historiam Britannicam… (1737) contains a print in which “a devil, who is driving the damned before him, is blowing a horn with a label issuing from his mouth and the words: ‘Out, out Arongt’.” Arongt resembles aroint but its existence does not clarify the etymology of either.

The opinions, as one can see, are many, but only one conclusion is almost certain. Shakespeare, a Stratford man, knew a local word, expected his audience to understand it even in London, and used it in his plays dated to the beginning of the seventeenth century. Thus, he did not invent aroint, and the suggestion that it is his adaptation of around cannot be entertained, for how would it then have passed into popular speech in that form? As follows from the facts summarized above, in addition to witches, cows in Cheshire understood aroint thee and the phrase became proverbial in some parts of England. The milkmaids’ experience notwithstanding, it will probably not be too risky to propose that aroint thee was coined to ward off witches, damned souls, and their ilk (arongt does look identical with aroint) and that only later it spread to less ominous situations. Perhaps its origin has not been discovered because nearly everybody glossed it as “begone, disappear, stand off.” But (and this is my main point) aroint thee may have meant something like beshrew thee, fie on you. Louis Marder, in updating Furness’s Macbeth (1963), said: “The local nature, the meaning, and form of the phrase, seem all opposed to its identity with Shakespeare’s Aroint,” because ryndta! in Cheshire and Lancashire is “merely a local pronunciation of ‘round thee’= move around.” Except for having doubts about the currency of ryndta in Lancashire, OED endorsed this verdict. In my opinion, the match is quite good. Ryndta does not necessarily have to go back to round thee, while the local character of the phrase cannot be used as an argument for or against its identity with what we find in Macbeth and King Lear.

At least as early as 1784, it was suggested that aroint has something to do with rauntree, one of several variants of the tree name rowan. This tree, perhaps better known as mountain ash, is famous in myth and folklore from Ancient Greece to Scandinavia.  One of its alleged virtues is the ability to deter witches and protect people and cattle from evil. The great Scandinavian god Thor was once almost drowned in a river because of the wiles of a mighty giantess but threw a great stone at her, was carried ashore, caught hold of a rowan tree, and waded out of the water; hence the tree’s name “Thor’s rescue.” It would be quite natural to shout rauntree or rointree, in order to chase away a witch: on hearing the terrible word, she would be scared and flee. Rowan is a noun of Scandinavian origin (Icelandic reynir, Norwegian raun; the earliest citations in OED do not predate the middle of the fifteenth century), so that various diphthongs, including oi, developed in it. An imprecation like a raun ~ reyn to thee seems to have existed and become aroint thee. The only lexicographer who entertained a similar idea was Ernest Weekley. He wrote: “Exact meaning and origin unknown. ? Connected with dialectal rointree, rowan-tree, mountain-ash, efficacy of which against witches is often referred to in early folklore.” I take it to be the most promising hypothesis of all. The word (rowan), pronounced differently in different dialects, reached England from Scandinavia, but the curse is probably local. In any case, its Scandinavian analogs have not been found.

One of its alleged virtues is the ability to deter witches and protect people and cattle from evil. The great Scandinavian god Thor was once almost drowned in a river because of the wiles of a mighty giantess but threw a great stone at her, was carried ashore, caught hold of a rowan tree, and waded out of the water; hence the tree’s name “Thor’s rescue.” It would be quite natural to shout rauntree or rointree, in order to chase away a witch: on hearing the terrible word, she would be scared and flee. Rowan is a noun of Scandinavian origin (Icelandic reynir, Norwegian raun; the earliest citations in OED do not predate the middle of the fifteenth century), so that various diphthongs, including oi, developed in it. An imprecation like a raun ~ reyn to thee seems to have existed and become aroint thee. The only lexicographer who entertained a similar idea was Ernest Weekley. He wrote: “Exact meaning and origin unknown. ? Connected with dialectal rointree, rowan-tree, mountain-ash, efficacy of which against witches is often referred to in early folklore.” I take it to be the most promising hypothesis of all. The word (rowan), pronounced differently in different dialects, reached England from Scandinavia, but the curse is probably local. In any case, its Scandinavian analogs have not been found.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Rowan by Ivan Shishkin, 1892. Public domain via Wikipaintings.org.

The post Out of Shakespeare: ‘Aroint thee’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By: RachelM,

on 2/19/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Religion,

Current Affairs,

oupblog,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

pope,

catholic church,

Pope Benedict XVI,

catholicism,

Humanities,

Benedict XVI,

*Featured,

vatican city,

abdicate,

Dictionary of Popes,

Papal resignation,

resign,

Add a tag

Pope Benedict XVI has led the Catholic Church since 2005, during a time of great change and difficulty. During his time as Pope, he rejected calls for a debate on the issue of clerical celibacy and reaffirmed the ban on Communion for divorced Catholics who remarry. He has also reaffirmed the Church’s strict positions on abortion, euthanasia, and gay partnerships. After eight years, Pope Benedict announced on Monday 11 February that he would step down as pontiff within two weeks. In his resignation statement the 85-year-old Pope said: “After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry.”

While abdication is not unheard of, it is the first papal resignation in almost 600 years. To give an overview of the history of papal resignations, we present selected entries from A Dictionary of Popes. (Full entries for the following Popes can be found on Oxford Reference.)

St Pontian (21 July 230–28 Sept. 235)

For most of his reign the Roman church enjoyed freedom from persecution as a result of the tolerant policies of Emperor Alexander Severus (222–35). Maximinus Thrax, however, acclaimed emperor in Mar. 235, abandoned toleration and singled out Christian leaders for attack. Among the first victims were Pontian and Hippolytus, who were both arrested and deported to Sardinia, the notorious ‘island of death’. Since deportation was normally for life and few survived it, Pontian abdicated (the first pope to do so), presumably to allow a successor to assume the leadership as soon as possible. He did so, according to the 4th-century Liberian Catalogue, on 28 Sept. 235, the first precisely recorded date in papal history (other apparently secure dates are based on inference).

St Marcellinus (30 June 296–?304; d. 25 Oct. 304)

On 23 Feb. 303, during St Marcellinus’s reign, Emperor Diocletian (284–305) issued his first persecuting edict ordering the destruction of churches, the surrender of sacred books, and the offering of sacrifice by those attending law-courts. Marcellinus complied and handed over copies of the Scriptures; he also, apparently, offered incense to the gods. His surrender of sacred books disqualified him from the priesthood, and if he was not actually deposed (as some scholars argue) he must have left the Roman church without an acknowledged head. The date of his abdication or deposition, however, is not known.

John XVII (16 May–6 Nov. 1003)

John XVII short-lived papacy is so obscure, the circumstances of his abdication, and indeed his death, are unknown.

Benedict IX (21 Oct. 1032–Sept. 1044; 10 Mar.–1 May 1045; 8 Nov. 1047–16 July 1048: d. 1055/6)

In 1032, Alberic III, head of the ruling Tusculan family, bribed the electorate and had his son Theophylact, elected as Pope, and the following day enthroned, with the style Benedict IX. Still a layman, he was not, as later gossip alleged, a lad of 10 or 12 but was probably in his late twenties; his personal life, even allowing for exaggerated reports, was scandalously violent and dissolute. If for twelve years he proved a competent pontiff, he owed this in part to native resourcefulness, but in part also to an able entourage and to the firm control which his father exercised over Rome. He was the only pope to hold office, at any rate de facto, for three separate spells.

St Peter Celestine V (5 July–13 Dec. 1294: d. 19 May 1296)

Naive and incompetent, and so ill educated that Italian had to be used in consistory instead of Latin, St Peter Celestine V let the day-to-day administration of the church fall into confusion.

Aware of his shortfalls, he considered handing over the government of the church to three cardinals, but the plan was sharply opposed. Finally, on 13 Dec. of the same year, he abdicated, was stripped off the papal insignia, and became once more ‘brother Pietro’.

And if you were wondering if there was any other way that a Pope could end their reign, the following Popes were deposed:

Liberius (17 May 352–24 Sept. 366)

A Roman by birth, he was elected at a time when the pro-Arian faction was in the ascendant in the east and Constantius II (337–61), now sole emperor, was taking steps to force the western episcopate to fall into line and join the east in anathematizing Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373), always the symbol of Nicene orthodoxy.

Since Liberius held out against this, resisting bribery and then threats, he was brought by force to Milan and then, proving unyielding, banished to Beroea in Thrace (and, as such, deposed). Here his morale collapsed, overcome by boredom, said Jerome, and under pressure from the local bishop, and, in painful contrast to his previous resolute stand, after two years he acquiesced in Athanasius’ excommunication, accepted the ambiguous First Creed of Sirmium (which omitted the Nicene ‘one in being with the Father’), and made abject submission to the emperor.

With the death of Constantius (3 Nov. 361), however, he was free to reassume his role as champion of Nicene orthodoxy.

Gregory VI (1 May 1045–20 Dec. 1046: d. late 1047)

An elderly man respected in reforming circles, John Gratian (who became Gregory VI) was archpriest of St John at the Latin Gate when his godson Benedict IX (see above), recently restored to the papal throne, made out a deed of abdication in his favour on 1 May 1045. A huge sum of money apparently changed hands; and according to most sources Benedict sold the papal office, whilst according to others the Roman people had to be bribed. The whole transaction remains obscure, probably because it was deliberately kept dark at the time.

The bribery was ultimately unsuccessful, and on 20 Dec. the next year Gregory VI appeared before the synod of Sutri, near Rome. After the circumstances of his election had been investigated, the emperor and the synod pronounced him guilty of simony in obtaining the papal office, and deposed him.

Gregory XII (30 Nov. 1406–4 July 1415: d. 18 Oct. 1417)

In their eagerness to see the end of the Great Schism (1378–1417), each of the fourteen Roman cardinals at the conclave following Innocent VII’s death swore that, if elected, he would abdicate provided Antipope Benedict XIII did the same or should die.

At first it seemed that the hopes everywhere aroused by his election would be speedily fulfilled. However, Gregory’s attitude altered; personal doubts and fears, combined with pressures from quarters apprehensive of what might ensue if he had to resign, made him eventually refuse the planned meeting with Benedict XIII. As the negotiations dragged on, Gregory’s cardinals became increasingly restive. They joined forces with four of Benedict’s cardinals at Livorno, made a solemn agreement with them to establish the peace of the church by a general council, and in early July sent out with them a united summons for such a council to meet at Pisa in March 1409.

Both popes were invited to attend the forthcoming council, but both naturally refused. The council of Pisa duly met, under the presidency of the united college of cardinals, in the Duomo on 25 Mar. Charges of bad faith, and even of collusion, were laid in great detail against both popes. At the 15th session, on 5 June, Gregory and Benedict were both formally deposed as schismatics, obdurate heretics, and perjurors, and the holy seat was declared vacant. On 26 June the cardinals elected a new pope, Alexander V.

Adapted from multiple entries in A Dictionary of Popes, Second edition, by J N D Kelly and Michael Walsh, also available online as part of Oxford Reference. This fascinating dictionary gives concise accounts of every officially recognized pope in history, from St Peter to Pope Benedict XVI, as well as all of their irregularly elected rivals, the so-called antipopes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Papal resignations through the years appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/13/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

linguistics,

guest,

indo-european,

host,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

hostis,

gasts,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The questions people ask about word origins usually concern slang, family names, and idioms. I cannot remember being ever asked about the etymology of house, fox, or sun. These are such common words that we take them for granted, and yet their history is often complicated and instructive. In this blog, I usually stay away from them, but I sometimes let my Indo-European sympathies run away with me. Today’s subject is of this type.

Guest is an ancient word, with cognates in all the Germanic languages. If in English its development had not been interrupted, today it would have been pronounced approximately like yeast, but in the aftermath of the Viking raids the native form was replaced with its Scandinavian congener, as also happened to give, get, and many other words. The modern spelling guest, with u, points to the presence of “hard” g (compare guess). The German and Old Norse for guest are Gast and gestr respectively; the vowel in German (it should have been e) poses a problem, but it cannot delay us here.

The hostess and her guests

The related forms are Latin

hostis and, to give one Slavic example, Russian

gost’. Although the word had wide currency (Italic-Germanic-Slavic), its senses diverged. Latin

hostis meant “public enemy,” in distinction from

inimicus “one’s private foe.” (I probably don’t have to add that

inimicus is the ultimate etymon of

enemy.) In today’s English,

hostile and

inimical are rather close synonyms, but

inimical is more bookish and therefore more restricted in usage (some of my undergraduate students don’t understand it, but everybody knows

hostile). However, “enemy” was this noun’s later meaning, which supplanted “stranger (who in early Rome had the rights of a Roman).” And “stranger” is what Gothic

gasts meant. In the text of the Gothic Bible (a fourth-century translation from Greek), it corresponds to

ksénos “stranger,” from which we have

xeno-, as in

xenophobia. Incidentally, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the best Indo-European scholars had agreed that Greek

ksénos is both a gloss and a cognate of

hostis ~

gasts (with a bit of legitimate phonetic maneuvering all of them can be traced to the same protoform). This opinion has now been given up;

ksénos seems to lack siblings. (What a drama! To mean “stranger” and end up in linguistic isolation.) The progress of linguistics brings with it not only an increase in knowledge but also the loss of many formerly accepted truths. However, caution should be recommended. Some people whose opinion is worth hearing still believe in the affinity between

ksénos and

hostis. Discarded conjectures are apt to return. Today the acknowledged authorities separate the Greek word from the cognates of

guest; tomorrow, the pendulum may swing in the opposite direction.

Let us stay with Latin hostis for some more time. Like guest, Engl. host is neither an alien nor a dangerous adversary. The reason is that host goes back not to hostis but to Old French (h)oste, from Latin hospit-, the root of hospes, which meant both “host” and “guest,” presumably, an ancient compound that sounded as ghosti-potis “master (or lord) of strangers” (potis as in potent, potential, possibly despot, and so forth). We remember Latin hospit- from Engl. hospice, hospital, and hospitable, all, as usual, via Old French. Hostler, ostler, hostel, and hotel belong here too, each with its own history, and it is amusing that so many senses have merged and that, for instance, a hostel is not a hostile place.

Unlike host “he who entertains guests,” Engl. host “multitude” does trace to Latin hostis “enemy.” In Medieval Latin, this word acquired the sense “hostile, invading army,” and in English it still means “a large armed force marshaled for war,” except when used in a watered down sense, as in a host of troubles, a host of questions, or a host of friends (!). Finally, the etymon of host “consecrated wafer” is Latin hostia “sacrificial victim,” again via Old French. Hostia is a derivative of hostis, but the sense development to “sacrifice” (through “compensation”?) is obscure.

The puzzling part of this story is that long ago the same words could evidently mean “guest” and “the person who entertains guests”, “stranger” and “enemy.” This amalgam has been accounted for in a satisfactory way. Someone coming from afar could be a friend or an enemy. “Stranger” covers both situations. With time different languages generalized one or the other sense, so that “guest” vacillated between “a person who is friendly and welcome” and “a dangerous invader.” Newcomers had to be tested for their intentions and either greeted cordially or kept at bay. Words of this type are particularly sensitive to the structure of societal institutions. Thus, friend is, from a historical point of view, a present participle meaning “loving,” but Icelandic frændi “kinsman” makes it clear that one was supposed “to love” one’s relatives. “Friendship” referred to the obligation one had toward the other members of the family (clan, tribe), rather than a sentimental feeling we associate with this word.

It is with hospitality as it is with friendship. We should beware of endowing familiar words with the meanings natural to us. A friendly visit presupposes reciprocity: today you are the host, tomorrow you will be your host’s guest. In old societies, the “exchange” was institutionalized even more strictly than now. The constant trading of roles allowed the same word to do double duty. In this situation, meanings could develop in unpredictable ways. In Modern Russian, as well as in the other Slavic languages, gost’ and its cognates mean “guest,” but a common older sense of gost’ was “merchant” (it is still understood in the modern language and survives in several derivatives). Most likely, someone who came to Russia to sell his wares was first and foremost looked upon as a stranger; merchant would then be the product of semantic specialization.

One can also ask what the most ancient etymon of hostis ~ gasts was. Those scholars who looked on ksénos and hostis as related also cited Sanskrit ghásati “consume.” If this sense can be connected with the idea of offering food to guests, we will again find ourselves in the sphere of hospitality. The Sanskrit verb begins with gh-. The founders of Indo-European philology believed that words like Gothic gasts and Latin host go back to a protoform resembling the Sanskrit one. Later, according to this reconstruction, initial gh- remained unchanged in some languages of India but was simplified to g in Germanic and h in Latin. The existence of early Indo-European gh- has been questioned, but reviewing this debate would take us too far afield and in that barren field we will find nothing. We only have to understand that gasts ~ guest and hostis ~ host can indeed be related.

There is a linguistic term enantiosemy. It means a combination of two opposite senses in one word, as in Latin altus “high” and “deep.” Some people have spun an intricate yarn around this phenomenon, pointing out that everything in the world has too sides (hence the merger of the opposites) or admiring the simplicity (or complexity?) of primitive thought, allegedly unable to discriminate between cold and hot, black and white, and the like. But in almost all cases, the riddle has a much simpler solution. Etymology shows that the distance from host to guest, from friend to enemy, and from love to hatred is short, but we do not need historical linguists to tell us that.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Conversation de dames en l’absence de leurs maris: le diner. Abraham Bosse. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post ‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/10/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Biography,

UK,

Dictionaries,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

lexicographer,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

james murray,

James A. H. Murray,

oxfordwords blog,

Peter Gilliver,

his scriptorium,

scriptorium,

constructed—slips,

Add a tag

Dictionaries never simply spring into being, but represent the work and research of many. Only a select few of the people who have helped create the Oxford English Dictionary, however, can lay claim to the coveted title ‘Editor’. In the first of an occasional series for the OxfordWords blog on the Editors of the OED, Peter Gilliver introduces the most celebrated, Sir James A. H. Murray.

By Peter Gilliver

If ever a lexicographer merited the adjective iconic, it must surely be James Augustus Henry Murray, the first Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary; although what he would have thought about the word being applied to him—in a sense which only came into being long after his death—can only be guessed at, though it seems likely that he would disapprove, given his strongly expressed dislike of the public interest shown in him as a person, rather than in his work. The photograph of him in his Scriptorium in Oxford, wearing his John Knox cap and holding a book and a Dictionary quotation slip, is almost certainly the best-known image of any lexicographer. But there is a lot more to this prodigious man.

If ever a lexicographer merited the adjective iconic, it must surely be James Augustus Henry Murray, the first Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary; although what he would have thought about the word being applied to him—in a sense which only came into being long after his death—can only be guessed at, though it seems likely that he would disapprove, given his strongly expressed dislike of the public interest shown in him as a person, rather than in his work. The photograph of him in his Scriptorium in Oxford, wearing his John Knox cap and holding a book and a Dictionary quotation slip, is almost certainly the best-known image of any lexicographer. But there is a lot more to this prodigious man.

In fact prodigious is another good word for him, for several reasons. He was certainly something of a prodigy as a child, despite his humble background. Born on 7 February 1837 in the Scottish village of Denholm, near Hawick, the son of a tailor, he reputedly knew his alphabet by the time he was eighteen months old, and was soon showing a precocious interest in other languages, including—at the age of 7—Chinese, in the form of a page of the Bible which he laboriously copied out until he could work out the symbols for such words as God and light. Thanks to his voracious appetite for reading, and what he called ‘a sort of mania for learning languages’, he was already a remarkably well-educated boy by the time his formal schooling ended, at the age of 14, with a knowledge of French, German, Italian, Latin, and Greek, and a range of other interests, including botany, geology, and archaeology. After a few years teaching in local schools—he was evidently a born teacher, and was made a headmaster at the age of 21—he moved to London, and took work in a bank. (It was only in 1855, incidentally, that he acquired the full name by which he’s become known: he had been christened plain James Murray, but he adopted two extra initials to stop his correspondence getting mixed up with that of the several other men living in Hawick who shared the name.) He soon began to attend meetings of the London Philological Society, and threw himself into the study of dialect and pronunciation—an interest he had already developed while still in Scotland—and also of the history of English. In 1870 an opening at Mill Hill School, just outside London, enabled him to return to teaching. He began studying for an external London BA degree, which he finished in 1873, the same year as his first big scholarly publication, a study of Scottish dialects which was widely recognized as a pioneering work in its field. Only a year later his linguistic research had earned him his first honorary degree, a doctorate from Edinburgh University: quite an achievement for a self-taught man of 37.

Dr. Murray, Editor

By this time the Philological Society had been trying to collect the materials for a new, and unprecedentedly comprehensive, dictionary of English for over a decade, but the project had gradually lost momentum following the early death of its first Editor, Herbert Coleridge. In 1876 Murray was approached by the London publishers Macmillans about the possibility of editing a dictionary based on the materials collected; the negotiations ultimately came to nothing, but the work which Murray did on this abandoned project was so impressive that when new negotiations were opened with Oxford University Press, and the search for an editor began again, it soon became clear that Murray was the only possible man for the job. After further negotiations, in March 1879 contracts were finally signed, for the compilation of a dictionary that was expected to run to 6,400 pages, in four volumes, and take 10 years to complete—and which Murray planned to edit while continuing to teach at Mill Hill School!

The Dictionary progresses. . .

As we now know, the project would end up taking nearly five times as long as originally planned, and the resulting dictionary ran to over 15,000 pages. Murray soon had to give up his schoolteaching, and moved to Oxford in 1885; even then progress was too slow, and eventually three other Editors were appointed, each with responsibility for different parts of the alphabet. Although for more than three-quarters of the time he worked on the OED there were other Editors working alongside him—he eventually died in 1915—and of course from the beginning he had a staff of assistants helping him, it is without question that he was the Editor of the Dictionary. (He soon had no need of those extra initials: a letter addressed simply to ‘Dr. Murray, Oxford’ would reach him without any difficulty, and he even had notepaper printed giving this as his address.) It was Murray who, in 1879, launched the great ‘Appeal to the English-speaking and English-reading public’ which brought most of the millions of quotation slips from which the Dictionary was mainly constructed—slips sent in from all parts of the English-speaking world, recording English as it was and had been used at all times and in all places. And it was during the early years of the project that all the details of its policy and style had to be settled, and that was Murray’s responsibility; the three later Editors matched their work to his as closely as they could. He was also responsible for more of the 15,000-plus pages of the Dictionary’s first edition than anyone else: the whole of the letters A–D, H–K, O, P, and all but the very end of T, amounting to approximately half of the total.

A dedicated man

What qualities enabled him to achieve this remarkable feat? It hardly needs to be said that he brought an extraordinary combination of linguistic abilities to the task: not just a knowledge of many languages, but the kind of sensitivity to fine nuances in English which all lexicographers need, in an exceptionally highly-developed form. He was also knowledgeable in a wide range of other fields. But one of his most striking qualities was his capacity for hard work, which once again deserves to be called prodigious. Throughout his time working on the Dictionary it was by no means unusual for him to put in 80 or 90 hours a week; he was often working in the Scriptorium by 6 a.m., and often did not leave until 11 p.m. Such a punishing regime would have destroyed the health of a weaker man, but Murray continued to work at this intensity into his seventies.

What qualities enabled him to achieve this remarkable feat? It hardly needs to be said that he brought an extraordinary combination of linguistic abilities to the task: not just a knowledge of many languages, but the kind of sensitivity to fine nuances in English which all lexicographers need, in an exceptionally highly-developed form. He was also knowledgeable in a wide range of other fields. But one of his most striking qualities was his capacity for hard work, which once again deserves to be called prodigious. Throughout his time working on the Dictionary it was by no means unusual for him to put in 80 or 90 hours a week; he was often working in the Scriptorium by 6 a.m., and often did not leave until 11 p.m. Such a punishing regime would have destroyed the health of a weaker man, but Murray continued to work at this intensity into his seventies.

Somehow he managed to combine his work with a vigorous family life; another image of him which deserves to be just as well known as the studious portraits in the Scriptorium is the photograph showing him and his wife surrounded by their eleven children, or the one of him astride a huge ‘sand-monster’ constructed on the beach during one of the family’s holidays in North Wales. He also found time to be an active member of his local community: he was a staunch Congregationalist, regularly preaching at Oxford’s George Street chapel, and an active member of many local societies, and frequently gave lectures about the Dictionary. It is just as well that his conviction of the value of hard work was combined with an iron constitution.

Somehow he managed to combine his work with a vigorous family life; another image of him which deserves to be just as well known as the studious portraits in the Scriptorium is the photograph showing him and his wife surrounded by their eleven children, or the one of him astride a huge ‘sand-monster’ constructed on the beach during one of the family’s holidays in North Wales. He also found time to be an active member of his local community: he was a staunch Congregationalist, regularly preaching at Oxford’s George Street chapel, and an active member of many local societies, and frequently gave lectures about the Dictionary. It is just as well that his conviction of the value of hard work was combined with an iron constitution.

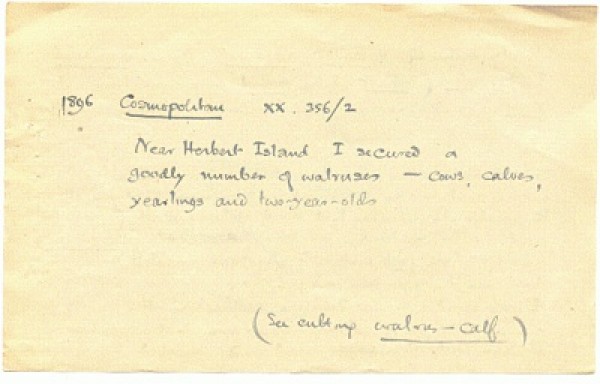

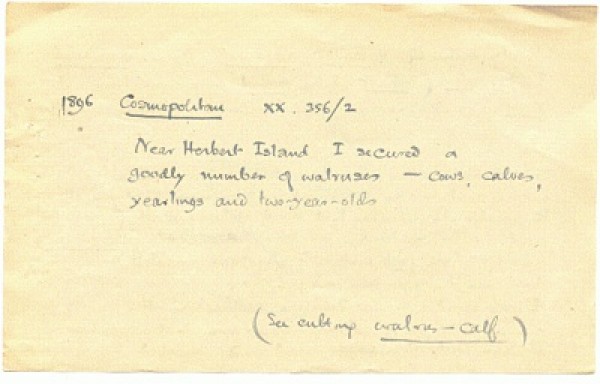

But there is one image which vividly captures another, crucial aspect of this remarkable man, an aspect which arguably underpins his whole approach to life and work. Tellingly, it is not an image of the man himself, but of one of the slips on which the Dictionary was written. The winter of 1896 saw one of Murray’s numerous marathon efforts to complete a section of the Dictionary, in this case the end of the letter D. Very late in the evening of 24 November he was at last able to put the finishing touches to the entry for the word dziggetai (a mule-like mammal found in Mongolia, an animal which Murray would never have seen, and an apt illustration of the Dictionary’s worldwide scope). At 11 o’clock, on the last slip for this word, he wrote: ‘Here endeth Τῷ Θεῷ μόνῳ δόξα.’ The Greek words mean ‘To God alone be the glory’, a phrase which is to be found several times (in various languages) in his writings. For Murray his work on the OED was a God-given vocation. He certainly came to believe that the whole course of his life appeared, in retrospect, to have been designed to prepare him for the work of editing the Dictionary; and perhaps it was only his strong sense of vocation which sustained him through the long years of effort.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Peter Gilliver is an Associate Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and is also writing a history of the OED.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words — past and present — from across the English-speaking world. Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number.

Subscribe to the OxfordWords blog via RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Dr. Murray, Oxford’: a remarkable Editor appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/9/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

Multimedia,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

odnb,

Research Tools,

Oxford Reference,

*Featured,

philip carter,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

oxford dnb,

Oxford Dictionaries Online,

Online Products,

Charlotte Buxton,

National Libraries Day,

Owen Goodyear,

Ruth Langley,

Add a tag

Ever wondered what the Latin word for owl is? Or what links Fred Perry and Ping Pong? Maybe not, but you may be able to find the answers to these questions and many more at your fingertips in your local library. As areas for ideas, inspiration, imagination and information, public libraries are stocked full of not only books but online resources to help one and all find what they need. They are places to find a great story, research your family or local history, discover the origins of words, advice about writing a CV, or help with writing an essay on topics from the First World War to feminism in Jane Austen.

Saturday 9 February 2013 is National Libraries Day in the UK, and here at Oxford we publish a variety of online resources which you can find in many local libraries. To help with the celebrations we have asked a selection of our editors to write a few words about what they feel the resource they work on offers you, why they find it so fascinating, and what it can do when put to the test! And here is what they said…

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Philip Carter, Publication Editor, Oxford DNB

What can the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography offer librarians and their patrons? Three things, I’d say.

First, with life stories of 58,552 people who’ve shaped British history, there’s always someone new to meet: the first woman to swim the English Channel, perhaps? Or the last person convicted of witchcraft; the owner of Britain’s first curry house, the founder of the Mothers’ Union, the man who invented the football goal net. Plus 58,547 others — Julius Caesar to Jade Goody.

Second, there are new things to discover about some familiar figures. Did you know, for instance, that the cookery writer Mrs Beeton grew up in the stand of Epsom racecourse? That before tennis Fred Perry led the world at ping pong? That Roald Dahl kept 100 budgerigars and was a chocaholic, or that Dora Russell (wife of Bertrand) was the first woman to wear shorts in Britain?

Third (and perhaps most importantly) there’s the chance for some social networking — British history style. Traditionally, print dictionaries laid out their content A to Z. Online, the opportunities for new research — by local and family historians, or by teachers and students — are so much greater. Of course, the ODNB online still allows you to look up people ‘A to Z’. But it can also bring historical figures together in new ways, often for the first time — by dates, places, professions or religious affiliations. Simplest is date: for instance, it takes moments to gather the 92 men and women who were born on 9 February (National Libraries Day, 2013), including (appropriately) 15 who made their mark as writers, editors, lexicographers, and publishers.

But it’s with place searching that new discoveries really become possible, and a dictionary of the nation’s past becomes a resource for local and family history — from street level upwards. Which historical figures have connections to my county? Who once lived in my village, town, or city? Who went to my school or college? Who was baptized in this church or buried in that churchyard?

If you’d like to try for yourself, we’ve guides on using the ODNB for local history and family research, as well as bespoke pages to introduce historical figures by individual library authority (for example, Aberdeenshire or Sheffield. If you’re a librarian and would like one to promote historical figures near you, just let us know.

Oxford English Dictionary

Oxford English Dictionary

Owen Goodyear, Editorial Researcher

For me, what makes the OED so fascinating is the fact it is one of a kind. What sets the OED apart is the attention it pays to each word’s history. I trained in historical linguistics, and when I look at an entry, I’m always drawn to the etymology first. Take the word owl. The Latin for owl is ulula, and the early modern German huhu, rather delightfully imitating the sound of the bird. Owl is also used for varieties of pigeon — not for the sound, but its distinctive ruff — and, apparently, moths and rays, for their barn-owl-like colouring. One such type of moth is more commonly known as the garden tiger moth, which leads me to look up tiger and find the theory that its name comes from the Avestan word for sharp or arrow… then I find myself distracted by tiger as a verb, meaning to prowl about like a tiger. Pretty much what I’m doing now, in fact, following the connections from entry to entry. It’s hard to resist. Like an owl to a flame, you might say.

Oxford Reference

Oxford Reference

Ruth Langley, Publishing Manager Reference

The new British citizenship test has been in the news lately — with commentators speculating that many people born and brought up in the UK would not be able to answer some of the questions on Britain’s history or culture. One of the wonderful things about living in Britain must surely be the access to free information found provided by the public library system, so I found myself wanting to remind all the lucky UK library users that they could find the answers they needed by logging onto Oxford Reference with their library cards. So, using a small sample of the questions featured in many newspapers, I decided to put Oxford Reference to the citizenship test — would it get the 75% necessary to prove itself well-versed in what it means to be British?

Searching for ‘Wiltshire monument’ across the 340 subject reference works on Oxford Reference, it correctly identifies Stonehenge as the multiple choice answer for the question on famous landmarks.

As I follow links from the information on Stonehenge to editorially recommended related content, I find results from OUP’s archaeology reference works which offer information on other ancient monument sites in Wiltshire like Avebury and Silbury Hill.

The admiral who died in 1805 causes no problems for our History content, and neither does the popular name for the 1801 version of the flag for the United Kingdom.

There are ten entries on St Andrew the patron Saint of Scotland, and I linger for a while to re-read his entry in one of the most colourful reference works on Oxford Reference, the Dictionary of Saints. The Dictionary of English Folklore quickly confirms that poppies are worn on Remembrance Day, and from that entry I follow a link to information about how poppies were used as a symbol of sleep or death on bedroom furniture and funerary architecture — my new fact for the day.

Other questions on the House of Commons and jury service take me to the extensive political and legal content on the site, and before long I am pleased to confirm that Oxford Reference has passed its citizenship test with flying colours.

I’ve been reminded along the way of the depth and richness of the content to be found on Oxford Reference covering all subject areas from Art to Zoology; the speed with which you can find a concise but authoritative answer to your question; the unexpected journeys you can follow as you investigate the links to related content around the site; and the pleasure in reading reference entries which have been written and vetted by experts.

Oxford Dictionaries Online

Oxford Dictionaries Online

Charlotte Buxton, Project Editor, Oxford Dictionaries Online

As a dictionary editor, I work with words on a daily basis, but I still can’t resist turning to Oxford Dictionaries Pro when I’m out of the office. It’s not just for those moments when I need to find out what a word means (although, contrary to what my friends and family seem to believe, I don’t actually know the definition of every word, so find myself looking them up all the time). I’m a particular fan of the thesaurus: why say idiot, after all, when you could use wazzock, clodpole, or mooncalf? Most importantly, I can access the site on the move. This helps to end those tricky grammar arguments in the pub — a few taps and I can confidently declare exactly when it’s acceptable to split an infinitive, whether we should say spelled or spelt, and if data centre should be hyphenated. And thus my reputation as an expert on all matters relating to language is maintained.

And now take our UK Public Library Members Quiz for a chance to win either £50 worth of Oxford University Press books or an iPod shuffle (TM).

The majority of UK public library authorities have subscribed to numerous Oxford resources. Your public library gives you access, free of charge within the library or from home to the world’s most trusted reference works. Learn more at our library resource center and in this video:

Click here to view the embedded video.

The Oxford DNB online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 165 life stories now available (including the lives of Alan Turing, Piltdown Man, Wallace Hartley, and Captain Scott). You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words — past and present — from across the English-speaking world. Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number.

Oxford Reference is the home of Oxford’s quality reference publishing bringing together over 2 million entries, many of which are illustrated, into a single cross-searchable resource. Made up of two main collections, both fully integrated and cross-searchable in the same interface, Oxford Reference couples Oxford’s trusted A-Z reference material with an intuitive design to deliver a discoverable, up-to-date, and expanding reference resource.

Oxford Dictionaries Online is a free site offering a comprehensive current English dictionary, grammar guidance, puzzles and games, and a language blog; as well as up-to-date bilingual dictionaries in French, German, Italian, and Spanish. We also have a premium site, Oxford Dictionaries Pro, which features smart-linked dictionaries and thesauruses, audio pronunciations, example sentences, advanced search functionality, and specialist language resources for writers and editors.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post National Libraries Day UK appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/8/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Food,

quiz,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

Food & Drink,

crescent,

croissant,

drink,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Arts & Leisure,

slickquiz,

Diner's Dictionary,

John Ayto,

ayto,

gastronomical,

scorch,

generously,

Add a tag

Did you know that ‘croissant’ literally means ‘crescent’ or that oranges are native to China? Do you realize that the word ‘pie’ has been around for seven hundred years in English or that ‘toast’ comes from the Latin word for ‘scorch’? John Ayto explores the word origins of food and drink in The Diner’s Dictionary. We’ve made a little quiz based on the book. Are you hungry for it?

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

John Ayto is a freelance writer and the author of many reference works, including the Dictionary of Slang, the Dictionary of Modern Slang, and Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms. Seasoned generously with literary wit, The Diner’s Dictionary is a veritable feast, tracing the origins and history of over 2,300 gastronomical words and phrases.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Quiz on the word origins of food and drink appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/6/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

monkey,

mars,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

mare,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

better,

gobelet,

word origins,

monthly gleanings,

Overused Words,

vaso,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

I am picking up where I left off a week ago.

Mare and Mars. Can they be related?

The chance is close to zero. Both words are of obscure origin, and attempts to explain an opaque word by referring it to an equally opaque one invariably come out wrong. Although Mars, the name of the Roman war god, has been compared with the Greek verb márnamai “I fight,” this comparison may be the product of folk etymology. Some festivals dedicated to Mars involved horses, but the connection was not direct. Since the success of campaigns depended on the good state of chariots, war and steeds formed a natural union. Mare has multiple Germanic and Celtic cognates. However, it may be a migratory word of Eastern origin. For example, Russian merin “gelding” has almost the same root. A similar case is Latin caballus “packhorse; nag,” later just “horse” and Russian kobyla “mare” (stress on the second syllable).

Monkey.

Along the same lines, I must defer judgment with regard to the word for “monkey” in Arabic, Farsi, and Romany. At the end of my post on monkey, I suggested that we might be dealing with a migratory animal name. If I am right, the etymology of one more hard word will be partly clarified.

Better.

In the post on suppletive forms, I wrote that better is the comparative of a nonexistent positive degree (good has a different root).The question from our correspondent concerned Farsi beh, behtar, behtarin. Are those forms related to better? Not being a specialist in Indo-Iranian, I cannot answer this question. (However, if h is a separate phoneme belonging to the root, the relation is unlikely.) I will only say that better is akin to Engl. boot in to boot and bootless (all such cognates refer to gain and improvement) and that the standard etymological dictionaries of Indo-European (Walde-Pokorny and Pokorny) mention only Sanskrit and Avestan congeners of better (Gothic batiza); they mean “happy.”

En gobelet (French) ~ en vaso (Spanish).

These phrases designate a vine pruned to the shape of a hollow cup. Was the drinking vessel named after the shape of the vine, or was the shape of the vine named after the drinking vessel? I am sure the second variant is correct.

Overused Words

As noted last time, I received a sizable list of words that the listeners of Minnesota Public radio “hate.” It is an instructive list. I also have my peeves. For example, I wince every time I hear that so-and so is a Renaissance man. In some circles, it suffices to know the correct spelling of principle and principal to become an equal of Leonardo. Fascinating is another enemy, and so is the cutting edge (in academia, to be on the cutting edge, one has to be interdisciplinary). Nothing is nowadays good, acceptable, or proper: the maid of all work is sustainable: sustainable behavior, sustainable budget, sustainable tourism—every quality and object has its sustainable niche (rhyming in the Midwest and perhaps everywhere with kitsch, witch, and bitch). Some of my “enemies” are pretentious Latinisms. For instance, I never accepted utilize outside its technical context (use is good enough for me) and morph for “change.” Why should things morph instead of changing? And why do students hope to utilize my notes? Do they want to recycle them?

I began to pay attention to other buzzwords only after they were pointed out to me:

Amazing.

True enough, newspapers and TV find themselves constantly enraptured. Their frame of mind is one of permanent astonishment and wonderment: the simplest things amaze them: a readable book, cold weather, and even cheap pizza. As a result, amazing has come to mean “worthy of notice.” It followed the same “trajectory” as Renaissance man. Rather scary are also the adjectives epic and surreal. The protagonists of epic poetry are larger than life, but with us every important event acquires “epic” dimensions. Likewise, though reality is full of surprises, every unexpected situation need not be called surreal.

Trajectory.

The word has been worked to death. Path, road, way, development, direction, and the rest have yielded to it. This holds for journalists and speech writers at all levels. President Obama: “I think Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not.”

Impact.

This word has killed influence and its synonyms. I remember the time when the concerned guardians of English usage fought the verb impact. Now both the verb and the noun have become the un-words of the decade. Everything “has an impact” and “impacts” its neighbors. Impact is a tolerably good word, but, like chocolate, it cloys the appetite and produces heartburn if consumed in great quantities.

I will now quote some of the messages I received. Perhaps our correspondents will comment on them:

Dialogue.

“I absolutely hate dialogue used as verb, as in let’s dialogue about that. Also hate go-to as in it’s my go-to snack or it’s my go-to workout.” Both do sound silly, for go-to (never a beauty) originated in contexts like this is the person to go to (= turn to) if you need good advice. Shakespeare would have been puzzled: in his days go to was a transparent euphemism for go to the devil. As for dialogue, it has succumbed to the powerful rule that has “impacted” English since at least the sixteenth century: every noun, and not only nouns, can be converted into a verb (consider “but me no buts,” “if ifs and buts were candy and nuts,” and the like). Sometimes the opposite process occurs: meet is a verb, and meet, a noun, came into being. It does not follow that we should admire the verb dialogue.

Folks.

“My least favorite word… when politicians use the word folks, like they are intimately familiar with their audience.” I agree! Folks should not be used as a doublet of folk.

Clearly.

“Whenever so-called experts weigh in on news stories, they preface their statements with the word clearly. Clearly somehow makes whatever they say irrefutably true.”

Actually.

“…count the number of times the word is used in a culture of growing mistrust of analysts and experts who make predictions about news before it happens…” I have waged a losing war against such adverbs (actually, really, clearly, definitely, certainly, doubtlessly) for years, but actually is the worst offender, a symptom of what I call advanced adverbialitis (–Where were you born? –Actually, I was born in California.)

Doubling down.

“The one I started hearing a lot this year is ‘So-and-so is doubling down on [a provocative statement or position]. Holy cow, political commentators, what did you do before this phrase crawled into your brains!” I guess they were milking some other venerable cow, possibly unrelated to gambling.

Evolve.

There was a complaint about the use of the verb evolve as meaning “develop; change” (“…so many people describe themselves or their opinions as ‘evolving’….”). In the past, I resented devolve as a synonym of degenerate, because I had been using this verb only in contexts like “I devolved all authority to my assistant,” but gradually accepted the other sense. By now I have heard evolve “change” so many times that it no longer irritates me (unlike morph).

Organic/natural.

In my talk show, I said that I am tired of hearing that nearly everything I buy is called organic or natural and was reprimanded: “There are strict standards set by government for the term organic, while the term natural is not regulated. You are maligning the organic food industry by proffering the incorrect information.” I stand corrected and apologize.

Random.

One of the listeners resented the promiscuous use of the adjective random (the epithet above is mine). Mr. Dan Kolz wrote in a letter to me: “In programming circles, a random value is one generated by the computer which is not predictable or predefined by the programmer. It can be used like: ‘I found a bug in test which generated random values as parameters’. It is sometimes used as a synonym for arbitrary or in a longer form ‘an arbitrarily chosen value’. This indicates that from the programmer’s perspective the value was unpredictable (if not actually from the user’s). It is in this sense that the word random could have acquired the meaning ‘selected or determined for no reason I know or could have predicted’, as in ‘I went to the party, but there were just a bunch of random people there’.” This strikes me as a reasonable explanation. Computer talk has really (clearly and actually) had a strong influence on Modern English. For instance, cross out and expunge have disappeared from the language: everything is now “deleted.”

May I repeat my old request? Sometimes people discover an old post of mine and leave a comment there. I have no chance to find it. Always leave your comments in the space allotted to the most recent posts. Above, I rejected a connection between mare and Mars. By way of compensation, you will see an equestrian print of the Roman war god, though I suspect that his horses were chargers rather than mares.

Char de Mars. Engraving. Wonders: Images of the Ancient World / Mythology — Mars. Source: NYPL.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/6/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

linguistics,

vernacular,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Peter Elbow,

Vernacular Eloquence,

academic speech,

linguistic pattern,

literary stylistics,

spoken language,

What Speech Can Bring to Writing,

written language,

incoherence,

Add a tag

By Peter Elbow

People who care about good language tend to assume that casual spoken language is full of chaos and error. I shared this belief till I did some substantial research into the linguistics of speech. There’s a surprising reason why we — academics and well-educated folk — should hold this belief: we are the greatest culprits. It turns out that our speech is the most incoherent. Who knew that working class speakers handle spoken English better than academics and the well-educated?

The highest percentage of well-formed sentences are found in casual speech, and working-class speakers use more well-formed sentences than middle-class speakers. The widespread myth that most speech is ungrammatical is no doubt based upon tapes made at learned conferences, where we obtain the maximum number of irreducibly ungrammatical sequences. (Labov 222. See also Halliday 132.)

Our language as it’s spoken / words by Geo. W. Day ; music by F.W. Isenbarth. c1898. Source: New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.