new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Martin Luther King Jr. Day in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: SoniaT,

on 1/19/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Rhetoric & Quotations,

martin luther king jr quotes,

mlk quotes,

Books,

Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

oxford dictionary of quotations,

elizabeth knowles,

martin luther king jr,

Add a tag

Each January, Americans commemorate the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., reflecting on the enduring legacy of the legendary civil rights activist. From his iconic speech at the 1963 March on Washington, to his final oration in Memphis, Tennessee, King is remembered not only as a masterful rhetorician, but a luminary for his generation and many generations to come. These quotes, compiled from the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, demonstrate the reverberating impact of his work, particularly in a time of great social, political, and economic upheaval.

On courage:

“A riot is at bottom the language of the unheard.”

Where Do We Go From Here? (1967) ch. 4

“If a man hasn’t discovered something he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.”

Speech in Detroit, 23 June 1963, in James Bishop The Days of Martin Luther King (1971) ch. 4

“Cowardice asks the question, ‘Is it safe?’ Expediency asks the question, ‘Is it politic?’ Vanity asks the question, ‘Is it popular?’ But Conscience asks the question, ‘Is it right?’”

Speech, 1967; in Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr. (1999) ch. 30

On equality:

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood…I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Speech at Civil Rights March in Washington, 28 August 1963, in New York Times 29 August 1963; see also jackson 413:13

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

Strength to Love (1963) ch. 5, pt. 2

On justice:

“Judicial decrees may not change the heart; but they can restrain the heartless.”

Speech in Nashville, Tennessee, 27 December 1962, in James Melvin Washington (ed.) A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1986) ch. 22

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963, in Atlantic Monthly August 1963

“We shall overcome because the arc of a moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Sermon at the National Cathedral, Washington, 31 March 1968, in James Melvin Washington A Testament of Hope (1991); see obama 571:3, parker 585:12

On inaction:

“The Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963, in Atlantic Monthly August 1963

“We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people.”

Letter from Birmingham Jail, Alabama, 16 April 1963

Image Credit: Tribute to Martin Luther King, Jr. Photo by U.S. Embassy New Delhi. CC by ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Martin Luther King, Jr. on courage, equality, and justice appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ErinF,

on 1/21/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fulton,

Online Products,

fulton county,

Georgia,

History,

statistics,

US,

Sociology,

Data,

african american,

African American Studies,

census,

Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

Research Tools,

martin luther king jr,

county,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

social explorer,

Sydney Beveridge,

demography,

Add a tag

By Sydney Beveridge

Martin Luther King, Jr. was the legendary civil rights leader whose strong calls to end racial segregation and discrimination were central to many of the victories of the Civil Rights movement. Every January, the United States celebrates Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to honor the activist who made so many strides towards equality.

Let’s take a look at the demographics of the legendary man’s hometown then and now to see how it has (and has not) changed. King was born in 1929, so we’ll examine Census data from 1930, 1940, and the latest Census and American Community Survey data.

His boyhood home is now a historic site, situated at 450 Auburn Avenue Northeast, in Fulton County (part of Atlanta). In 1930, Fulton County had a population of 318,587 residents. A little over two thirds of the population was white (68.1 percent) and almost one third of the population was African American (31.9 percent). Today, the 920,581-member population split is nearly even at 44.5 percent white and 44.1 percent African American, according to 2010 Census data. Fulton’s population is more African American than the United States as a whole (12.6 percent), but not as as much as Atlanta (54.0 percent).

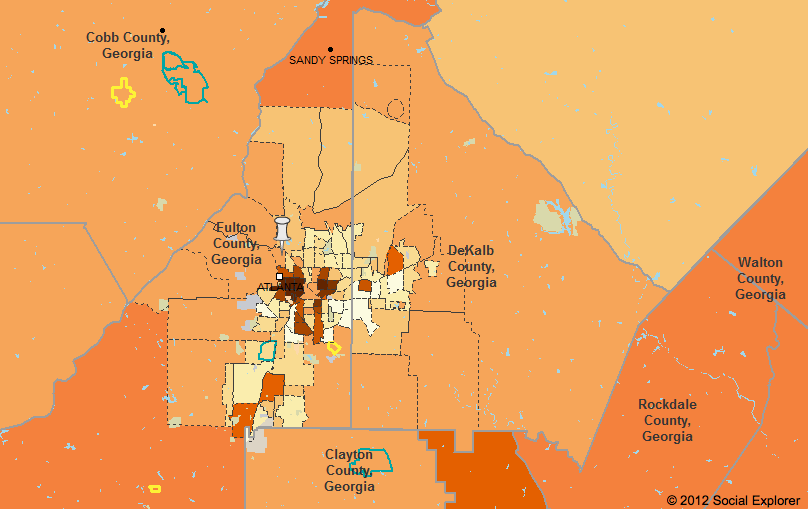

A closer look at 1940s Census data of the Atlanta area offers more detail about where the black and white populations lived. The following map shows the distribution of the black population in the Atlanta of King’s youth. Plainly, African Americans lived together, largely apart from whites.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 1940 (click map to explore)

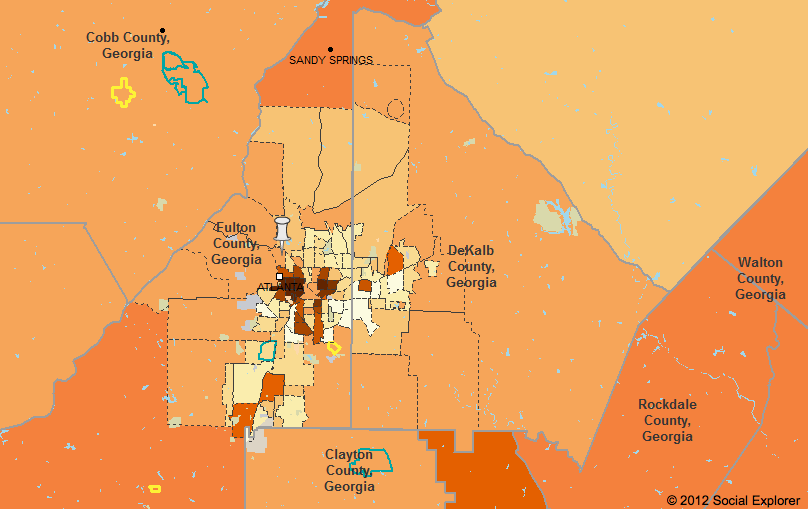

For comparison, the following map shows where the black population lives today. Now the black population has expanded in the metro area, but still seems to be quite segregated.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 2010 (click map to explore)

Reflecting on a century after the end of slavery, King said in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

The quest for equal rights and freedoms made up part of a larger vision. In 1967, he spoke of aspiring for full equality at a speech at the Victory Baptist Church in Los Angeles:

Our struggle in the first phase was a struggle for decency. Now we are in the phase where there is a struggle for genuine equality. This is much more difficult. We aren’t merely struggling to integrate the lunch counter now. We’re struggling to get some money to be able to buy a hamburger or a steak when we get to the counter…

He went on to say that this would require a commitment of not only political initiative but also money: “It didn’t cost the nation one penny to integrate lunch counters. It didn’t cost the nation one penny to guarantee the right to vote. The problems that we are facing today will cost the nation billions of dollars.”

In 1968, King and other activists launched the Poor People’s Campaign, advocating for economic justice to address these imbalances in opportunity and resources. A few months later, he was assassinated.

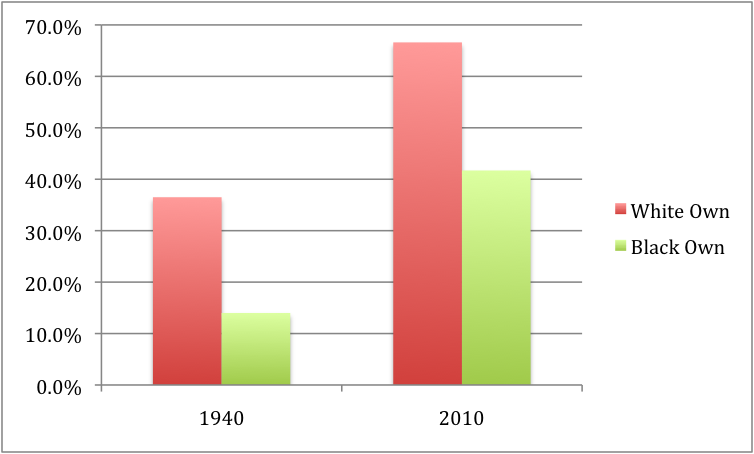

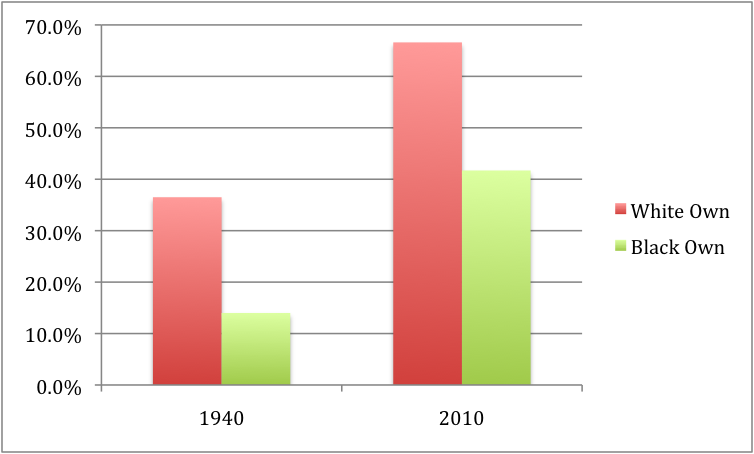

We can look at different socioeconomic indicators to measure the country’s progress towards equality. According to 1940 Census data, more than a third (36.5 percent) of housing units in Fulton County where whites lived were owner occupied, compared to less than a seventh (14.0 percent) of the housing units where African Americans lived.

Today, home ownership increased for both groups, but the gap remains. Two thirds (66.6 percent) of white households are owner-occupied, compared to two fifths (41.7 percent) of all black households.

Home Ownership Comparison in Fulton, GA, by Race

Let’s examine other measures of equality to see examples of additional gaps.

The unemployment rate is nearly twice as high among African Americans (17.9 percent) compared to among whites nationwide (9.5 percent). That gap is even more pronounced in Fulton County, where the unemployment rate for whites is 7.7 percent, while the unemployment rate for African Americans is 20.4 percent.

The percent of those living below poverty is also higher in the black community (27.2 percent) than in the white community (12.5 percent). While both groups are better off in Fulton County than the rest of the US, the poverty rate gap is even larger (8.2 percent among whites and 26.6 percent among African Americans in Fulton).

Similarly, while both groups are better educated in Fulton County compared to the rest of the US, nearly two thirds (62.4 percent) of white adults in the county have BA degrees or more, while just one quarter (25.3 percent) of the black population have the same level of education. The college attainment gap is 11.6 percentage points nationwide, but 37.1 percentage points in Fulton County.

While much progress towards freedom and equality has been made since King’s time, chronic gaps persist, even in his own backyard. The data show that 50 years after the “I Have a Dream Speech,” equal opportunity and socioeconomic status continue to lag behind equal rights.

Sydney Beveridge is the Media and Content Editor for Social Explorer, where she works on the blog, curriculum materials, how-to-videos, social media outreach, presentations and strategic planning. She is a graduate of Swarthmore College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. A version of this article originally appeared on the Social Explorer blog. You can use Social Explorer’s mapping and reporting tools to investigate dreams, freedoms, and equality further.

Social Explorer is an online research tool designed to provide quick and easy access to current and historical census data and demographic information. The easy-to-use web interface lets users create maps and reports to better illustrate, analyze and understand demography and social change. From research libraries to classrooms to the front page of the New York Times, Social Explorer is helping people engage with society and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Checking in on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream, with data appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy Martin Luther King, Jr. Day! It’s been a super busy weekend, and so I decided this post was going to tell you about my favorite Martin Luther King Jr. activity!  I hope however you are celebrating today that you are doing it with loved ones and remembering what this day is all about–fighting for what we believe in–fighting for equal rights for all people. (Maybe you are even watching President Barack Obama take the oath for the 2nd time!)

I hope however you are celebrating today that you are doing it with loved ones and remembering what this day is all about–fighting for what we believe in–fighting for equal rights for all people. (Maybe you are even watching President Barack Obama take the oath for the 2nd time!)

Here is a lesson that introduces Martin Luther King, Jr to the kids and also teaches voice, one of the six traits of writing. It also features the book written by Martin Luther King, Jr.’s sister, My Brother Martin. You can find the lesson plan at this link: http://margodill.com/blog/2010/01/13/wacky-wednesday-ideas-for-lesson-plans-for-martin-luther-king-jr-day/

If you have a great resource, link, book, or favorite lesson plan for Martin Luther King, Jr, please share it.

By:

Administrator,

on 1/13/2010

Blog:

Margo Dill's Read These Books and Use Them!

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Picture Book,

Lesson Plans,

Wacky Wednesday,

Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

Elementary Educators,

six traits of writing,

Books With Social Studies Content,

Writing Skills,

Making Book to Book Comparisons,

Farris Christine King,

Lesson Plans for Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

My Brother Martin,

Add a tag

photo by BlatantNews.com www.flickr.com (photo is in public domain)

photo by BlatantNews.com www.flickr.com (photo is in public domain)

One of my favorite lessons plans for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day I found when I was a writing specialist at Fairmount Elementary School. This lesson teaches children about Martin Luther King, Jr. AND teaches them about that elusive 6 plus one writing trait: voice. Plus, it’s super easy!

You need two books about Martin Luther King, Jr. One should be My Brother Martin, and the other one can be any fact book that you have for kids about Martin Luther King, Jr. Here’s the example:

First read the fact book to your students or your children. Ask them to remember one or two facts they can tell you when you finish reading. Discuss the book. Ask children to rate the book on a scale of 1 to 10. Next read My Brother Martin for this lesson plan for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, and ask students to remember one or two facts that they learn in the book. Discuss the book and ask them to rate it.

Next ask students if they want to rate the first book again, and they will want to rate it lower. THEY SHOULD love the book My Brother Martin for the voice and personal glimpse of his life you get from his sister. (Although you’ll always have one or two children that don’t like it better because it’s too long!  ) Talk to children about how the voice makes a huge difference in the enjoyment of the book. Whose voice is narrating, My Brother Martin? His sister’s! Whose voice is narrating the nonfiction fact book? An author who did research.

) Talk to children about how the voice makes a huge difference in the enjoyment of the book. Whose voice is narrating, My Brother Martin? His sister’s! Whose voice is narrating the nonfiction fact book? An author who did research.

See where I’m going here. . .

You can also use this lesson as an introduction to personal narratives. I love lessons that (1) share books (2) cover more than one topic at a time (3) get kids thinking!

By: Rebecca,

on 1/16/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Biography,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

civil rights,

African American Studies,

aanb,

African American History,

AASC,

Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

mlk,

A. Leon Higginbotham Jr.,

Add a tag

Since Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day I thought it would be nice to highlight another important civil rights leader, A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. This excerpt comes from The Oxford African American Studies Center. It was written by Edward L. Jr. Lach and published in the African American National Biography. In celebration of next week’s Inauguration and in commemoration of Black History Month in February, the Oxford African American Studies Center is available to the public for free until March 1st. Visit here for instructions on how to login or use username:barackobama, password:president.

A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., jurist and civil rights leader, was born Aloysius Leon Higginbotham in Trenton, New Jersey, the son of Aloysius Leon Higginbotham Sr. , a laborer, and Emma Lee Douglass , a domestic worker. While he was attending a racially segregated elementary school, his mother insisted that he receive tutoring in Latin, a required subject denied to black students; he then became the first African American to enroll at Trenton’s Central High School. Initially interested in engineering, he enrolled at Purdue University only to leave in disgust after the school’s president denied his request to move on-campus with his fellow African American students. He completed his undergraduate education at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where he received a BA in Sociology in 1949 . In August 1948 he married Jeanne L. Foster ; the couple had three children. Angered by his experiences at Purdue and inspired by the example of Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall , Higginbotham decided to pursue a legal career. He attended law school at Yale and graduated with an LLB in 1952 .

Although Higginbotham was an honors student at Yale, he encountered racial prejudice when he tried to find employment at leading Philadelphia, law firms. After switching his sights to the public sector, he began his career as a clerk for the Court of Common Pleas judge Curtis Bok in 1952 . Higginbotham then served for a year as an assistant district attorney under the future Philadelphia mayor and fellow Yale graduate Richardson Dilworth . In 1954 he became a principal in the new African American law firm of Norris, Green, Harris, and Higginbotham and remained with the firm until 1962 . During the same period he became active in the civil rights movement, serving as president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); he was also a member of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission.

Between 1960 and 1962 Higginbotham served as a special hearing officer for conscientious objectors for the United States Department of Justice. In 1962 President John F. Kennedy appointed him to the Federal Trade Commission, making him the first African American member of a federal administrative agency. Two years later President Lyndon Johnson appointed him as U.S. District Court judge for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania; at age thirty-six, he was the youngest person to be so named in thirty years. In 1977 President Jimmy Carter appointed him to the U.S. Federal Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit in Philadelphia. He became chief judge in 1989 and remained in the position until his retirement in 1993 .

As a member of the federal bench, Higginbotham authored more than 650 opinions. A staunch liberal and tireless defender of programs such as affirmative action, he became equally well known for his legal scholarship, with more than one hundred published articles to his credit. He also published two (out of a planned series of four) highly regarded books that outlined the American struggle toward racial justice and equality through the lens of the legal profession: In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, the Colonial Period ( 1978 ), in which he castigated the founding fathers for their hypocrisy in racial matters, and Shades of Freedom: Racial Politics and Presumptions of the American Legal Process ( 1996 ).

Higginbotham also taught both law and sociology at a number of schools, including the University of Michigan, Yale, Stanford, and New York University. He enjoyed a long relationship with the University of Pennsylvania, where he was considered for the position of president in 1980 before deciding to remain on the bench. Following his retirement in 1993 , Higginbotham taught at Harvard Law School and also served as public service professor of jurisprudence at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. In addition, he served on several corporate boards and worked for the law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton, and Garrison in both New York and Washington.

Although most of his career was spent outside the public limelight, Higginbotham came to the forefront of public attention in 1991 when he published an open letter to the Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Castigating Thomas for what he viewed as a betrayal of all that he, Higginbotham, had worked for, Higginbotham stated, “I could not find one shred of evidence suggesting an insightful understanding on your part of how the evolutionary movement of the Constitution and the work of civil rights organizations have benefited you.” Although widely criticized for his stance, Higginbotham remained a critic of Thomas’s after he joined the Supreme Court and later attempted to have a speaking invitation to Thomas rescinded by the National Bar Association in 1998 .

In his later years Higginbotham filled a variety of additional roles. He served as an international mediator at the first post-apartheid elections in South Africa in 1994 , lent his counsel to the Congressional Black Caucus during a series of voting rights cases before the Supreme Court, and advised Texaco Inc. on diversity and personnel issues when the firm came under fire for alleged racial discrimination in 1996 . In failing health, Higginbotham’s last public service came during the impeachment of President Bill Clinton in 1998 , when he argued before the House Judiciary Committee that there were degrees of perjury and that President Clinton’s did not qualify as “an impeachable high crime.” The recipient of several honorary degrees, Higginbotham also received the Raoul Wallenberg Humanitarian Award ( 1994 ), the Presidential Medal of Freedom ( 1995 ), and the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal ( 1996 ). After he and his first wife divorced in 1988 , Higginbotham married Evelyn Brooks, a professor at Harvard, and adopted her daughter. He died in a Boston hospital after suffering a series of strokes.

Although he never served on the Supreme Court, Higginbotham’s impact on the legal community seems certain to continue. A pioneer among African American jurists, he also made solid contributions in the areas of legal scholarship, training, and civil rights.

[...] topic. The Oxford University Press chose to honor Martin Luther King Jr day (last Monday) with an article on another prominent civil rights leader in the United States, A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. Although Judge Higginbotham was not as well known [...]