new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: mg historical fiction, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 17 of 17

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: mg historical fiction in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Becky Laney,

on 2/26/2016

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

coming of age,

J Fiction,

Scholastic,

mg historical fiction,

MG Fiction,

review copy,

mg historical,

j historical,

2016,

2016 Cybils-Eligible,

books reviewed in 2016,

Add a tag

Ruby Lee & Me. Shannon Hitchcock. 2016. Scholastic. 224 pages. [Source: Review copy]

I loved, loved, loved Shannon Hitchock's Ruby Lee and Me. This middle grade historical novel is set in the 1969, I believe. It will be a year of BIG change for the heroine, Sarah Beth Willis. School integration is probably one of the least of her worries. First, her sister, Robin, is run over by a car. Sarah worries a lot. Will her sister die? will she wake up from the coma? Will she walk and run and play again? Will her sister blame her for the accident? Will her parents blame her for the accident? Can she ever forgive herself for reading a library book instead of keeping both eyes on her sister every single moment of the afternoon? Second, because of finances, her family will be moving in with her grandparents. Now Sarah loves, loves, loves to visit the family farm and to spend time with each of her grandparents. But to move away from her house, her room, her school, her neighborhood, her friends and to have to start all over again in a new place?! It's scary. The one person she does know--and is quite good friends with--is the one person the adults in her life tell her she CAN'T spend time with in town, at school: Ruby Lee.

Ruby Lee's grandma and Sarah's grandma grew up as friends, and, are still quite close--in their own way, in their own private, behind-the-scenes way. But whites and blacks can't be friends publicly and openly, can they?! School integration is happening in the fall. Ruby Lee and Sarah Beth will be in the same class. Sarah really wants to be at-school friends too. Ruby Lee is hesitant. Does Sarah know what she's getting herself into? Is it something she's comfortable with too? Tension is only getting worse between races: for the school will be getting African American teachers as well as students. And Sarah and Ruby Lee will be taught by an African American. A lot of parents are, at the very, very least concerned, and, at worst, ANGRY and upset by this. Sarah's family is fine with this, by the way.

Ruby Lee and Me is about race and school integration. But it isn't only about that. It is about friendship and family. How do you make a friend? How do you keep a friend? How do friends help one another? When is a friendship worth fighting for or standing up for? How do friends resolve disagreements and fights? I liked the focus on Ruby Lee and Sarah Beth. But I also appreciated the family focus. I loved getting to know Sarah, Robin, the grandparents, and parents. I also appreciated the community librarian! Readers do get a first impression of the teacher as well. Part of me wishes the book followed the girls past meet the teacher night and well into their school year.

Another aspect of the novel was faith--faith in GOD. I loved that aspect of it. Not enough books today are written with a good, strong, solid Christian faith tradition. The family's faith is presented realistically and naturally.

Anyone looking for a historical coming-of-age novel with strong characterization should read Ruby Lee and Me.

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

Becky Laney,

on 9/3/2015

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA Fiction,

Random House,

mg historical fiction,

MG Fiction,

review copy,

YA Historical,

MG Realistic Fiction,

2015,

2015 Cybils-eligible,

books reviewed in 2015,

Add a tag

Seventh Most Important Thing. Shelley Pearsall. 2015. Random House. 288 pages. [Source: Review copy]

The Seventh Most Important Thing by Shelley Pearsall is loosely based on a true story. One of the characters in the novel was an actual person, an artist named James Hampton. An author's note tells more of his story. I do wish I'd known this at the start; that is one reason I'm beginning my review with this 'essential' information.

Arthur T. Owens is the hero of The Seventh Most Important Thing; the book is a coming-of-age story set in 1963. Arthur has not been having an easy time of it, life has not been the same for him since his father died. And one day he loses it. He sees "the junk man" walking down the street pushing his cart full of junk, and the man is wearing his father's hat. He picks up a brick, takes aim, and hits him. Fortunately, it hits him on the arm and not in the head. James Hampton is "the junk man" and he urges the court to show Arthur mercy, and sentence him to community service. His community service will be working for "the junk man." Arthur has a list of SEVEN items to collect each Saturday. And the list is the same week to week. To collect these items, he'll need to walk the streets and neighborhoods picking up trash and even going through people's trash. It won't be easy for him, especially at first, to lower himself like that. But this process changes him for the better. And there comes a time when readers learn alongside Arthur just what "the junk man" does with his junk. And the reveal is worth it, in my opinion.

The Seventh Most Important Thing is definitely character-driven and not plot-driven. It's a reflective novel. The focus is on Arthur, on his family, on his new friendships and relationships, on the meaning of life. I liked the characters very much. The story definitely worked for me.

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Indian Captive: The Story of Mary Jemison. Lois Lenski. 1941. HarperCollins. 298 pages. [Source: Bought]

I don't remember reading Indian Captive as a child, and that may be a good thing. I'm not sure I would have--could have--appreciated it back then. Not that the book isn't for children, but I was a sensitive reader, and this one would have proved unsettling at times. I should mention that the book is set in the 1750s and 1760s.

Indian Captive is the story of Mary Jemison. (Though she's called Molly throughout the book, I believe.) As a girl, twelve years old, if I recall, she's taken captive along with her family by Indians. The night before the capture, they'd been warned by a frantic neighbor. The neighbor was advising anyone and everyone he came into contact with to run, that danger was imminent. Would it have made a difference if he'd listened? Maybe, but, probably not. Molly is the only survivor from her family. Not that she realizes this until the end of the novel. Though the Indians captured a dozen or so people initially, at the end, it was narrowed down to two. Molly was bought (though I'm not sure if sold/bought are the right words?) by two grieving women. For better or worse, she's been adopted by the tribe, and her new life has begun. While at first she struggles to make peace with all the changes, she does eventually come to accept her new reality and to even embrace it. That doesn't mean that when she comes across a white man (or woman) that she doesn't excitedly start speaking English. But it means that she finds a way to belong and does in fact find her identity within the tribe.

Indian Captive is rich in detail. It's historical fiction that seeks to capture a way of life, a culture (Seneca). Day by day, season by season, year after year. Details are layered throughout. As an adult reader, I must admit I'm skeptical of any book from this time period with Indians as the subject. Is the portrayal of Indian life accurate? fair? insulting? offensive? My guess is that it's better than some perhaps, but, not necessarily great. © 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

Becky Laney,

on 4/1/2015

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Newbery,

J Historical Fiction,

J Fiction,

World War II,

mg historical fiction,

children's classic,

MG Fiction,

1989,

books reviewed in 2015,

Newbery Reading Challenge,

Add a tag

Number the Stars. Lois Lowry. 1989. (Won Newbery in 1990) 137 pages. [Source: Bought]

Number the Stars was probably one of the first fiction books I read about the Holocaust and World War II. (I know I also read The Hiding Place and The Diary of Anne Frank, but both of those are nonfiction.) What did I remember about Number the Stars after all these years? Well, I remembered that it was about a young girl who had a Jewish best friend. I remembered that the girl's family helped the friend and her family get out of Denmark. I remembered the intense scene where German soldiers come to her house looking for hidden Jews. But most of the details had faded away. So it was definitely time for me to reread.

Annemarie is the heroine of Number the Stars. I loved her. I loved her courage and loyalty. Ellen is Annemarie's best friend. I love that readers get an opportunity to see these two be friends before it gets INTENSE. I also love Annemarie's family. I do. I don't think I properly appreciated them as a child reader. One thing that resonated with me this time around was Annemarie's older sister, her place in the story. The setting. I think the book did a great job at showing what it could have been like to grow up in wartime with enemy soldiers all around. In some ways it was the little things that I loved best. For example, how Annemarie, Ellen, and Kirsti (Annemarie's little sister) play paper dolls together, how they act out stories, in this case they are acting out scenes from Gone with The Wind. I think all the little things help bring the story to life and make it feel authentic.

For a young audience, Number the Stars has a just-right approach. It is realistic enough to be fair to history. It is certainly sad in places. But it isn't dark and heavy and unbearable. The focus is on hope: there are men and women, boys and girls, who live by their beliefs and will do what is right at great risk even. Yes, there is evil in the world, but, there is also good.

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

Becky Laney,

on 2/22/2015

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

books reviewed in 2015,

books reread in 2015,

Laura Ingalls Wilder,

series books,

J Fiction,

Newbery Honor,

mg historical fiction,

children's classic,

MG Fiction,

1937,

library book,

j historical,

Add a tag

On the Banks of Plum Creek. Laura Ingalls Wilder. 1937. 340 pages. [Source: Library]

I love Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House series. I do. And On the Banks of Plum Creek, while not my absolute favorite--that would be The Long Winter or possibly These Happy Golden Years--is worth rereading every few years. One thing I hadn't noticed until this last reread is that the Ingalls' family celebrates three Christmases in this one book!

Plenty of things happen in On The Banks of Plum Creek:

- the family moves into a sod house

- the family moves into a wooden house with real glass windows

- the family gets oxen and horses

- the girls start school

- the family attends church

- crops are planted and lost

- Pa leaves the family behind twice to go in search of work

- hard weather is endured

- Laura gets in and out of trouble (she almost drowns in this one)

The book is enjoyable and satisfying. I love the illustrations by Garth Williams. I remember them just as well as I do the text itself.

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

Becky Laney,

on 1/21/2015

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

war,

brothers and/or sisters,

dysfunctional families,

J Fiction,

World War II,

mg historical fiction,

mg historical,

j historical,

2015,

2015 Cybils-eligible,

books reviewed in 2015,

Add a tag

The War That Saved My Life. Kimberly Brubaker Bradley. 2015. Penguin. 320 pages. [Source: Library]

"Ada! Get back from that window!" Mam's voice, shouting. Mam's arm, grabbing mine, yanking me so I toppled off my chair and fell hard to the floor.It should come as no surprise that I loved, loved, loved Kimberly Brubaker Bradley's The War That Saved My Life. It's my kind of book. It's set in Britain during World War II. (To be honest, it could be set practically anywhere during World War II, and I'd want to read it.) It reminded me of

Good Night, Mr. Tom which is a very good thing since I loved that one so very much!

Ada's existence before the war was bleak. Because of her club foot, Ada is verbally and psychically abused by her mother. She's restricted to staying in the family's one room apartment, and she's discouraged from even looking out the window. She hasn't been outside ever as far as she knows--can remember. Her younger brother, Jamie, may not be as abused as his older sister. But neglected and malnourished? Definitely. He at least gets to leave the house to go to school, even if he isn't leaving the house clean.

When London's children begin to be evacuated days before war is declared, their mother agrees to send Jamie off to the country. She has no plans of sending Ada, however, telling her that no one in the world would want her--would put up with her. Ada, who has secretly been teaching herself to stand and even to walk, sneaks away with her younger brother. The two of them need to be together.

Susan reluctantly takes the two children into her home. It's not anything against Jamie and Ada, she says, it's just that she doesn't feel adequate enough to take care of anyone else. If truth be told, she sometimes struggles to take care of herself. Since Becky died, she's been isolating herself, often depressed. But Susan finds herself caring for these two children very much. Could it be she's found her family at last?

Ada and Jamie are difficult, no question. Ada is not used to being treated decently let alone kindly. She doesn't know how to respond and react to love and tenderness and respect. And the fact that Ada knows that it's temporary isn't helping. But Ada will slowly but surely be transformed by the war. One thing that helps Ada tremendously is Butter, a pony. (Butter belonged to Becky, a woman readers never actually meet, but, Susan talks about her often with much love and affection.) Ada teaches herself to ride, and her confidence increases almost daily.

Ada, Jamie, and Susan are all well-developed characters. I cared about all of them. Readers also meet plenty of other villagers. The story has plenty of drama!

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Chasing Freedom: The Life Journeys of Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony Inspired by Historical Facts. Nikki Grimes. Illustrated by Michele Wood. 2015. [January 2015] Scholastic. 56 pages. [Source: Review copy]

First sentence:

It is 1904, a year in which the 28th Annual Convention of the New York State Suffrage Association met in Rochester, New York. On this occasion, Susan B. Anthony will introduce the guest speaker, the legendary Harriet Tubman. Historical fiction based on a what-if, the what-if being "What if Harriet Tubman and Susan B. Anthony sat down over tea to reminisce about their extraordinary lives?" While the two women certainly met--at the very least twice since they spoke at the same conferences--there is no evidence that these two were friends or good friends who would sit down and spend an hour or two in conversation sharing their lives over cups of tea.

The whole book is a dialogue between the two women taking place in 1904. Their life stories are told alternately. This worked some of the time. Other times I felt the two were not so much connecting and sharing so much as talking AT one another. Susan being so focused on telling details of her life and Harriet being so focused on telling details from her life that the two were just being polite waiting for their turn to steer the conversation back to themselves. Not every page reads that way, of course. But it sometimes did. One thing that both women seemed to have in common is an admiration almost an idolization of John Brown.

For those interested in learning the basics about these two women, this book is certainly an interesting place to start. While it is fiction, the stories they are telling are based on facts. Readers will learn a handful of things about each woman and the significance of both women in history.

I liked the layout of this one. On one side, readers get text. On the other side, readers see lovely illustrations. I loved the illustrations!!!

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Native Americans in Children’s Literature

By

Jennifer Porter

Just over a year ago, my then fifth grade homeschooled daughter said to me, in the midst of reading historical fiction aloud with her, “I am sick and tired of these books about the so-called terrible Indians when it was the white people who stole their land. Aren’t there any books told by the Indians?”

I answered, “I don’t know. But you’re right, these books have not told the truth.” And we talked about how our ancestors were both the Europeans that came to America and stole the land and also the Native Americans that fought back against the invasion. I promised to find her books that would honor our American Indian ancestors, and by telling the truth, also honor our European ancestors.

After reading countless books and researching this issue, I was left with some conclusions. One, there is a plethora of offensive children’s books about Native Americans and two, it is an enormous undertaking to write about Native Americans. And it seems lately, that there is an opening in our culture to begin an earnest discussion about the history of the American Indian. For years I have been researching the tribes my American Indian ancestors came from, and it is possible now through advanced DNA testing to get some answers. It has become popular to find our ancestors. There are genealogy shows about celebrities on television and there are popular websites devoted to family history, such as ancestry.com.

Recently, PBS ran a series of American history shows from the perspective and viewpoint of the American Indian. And last October, President Obama declared November 2009 as Native American Heritage Month. Native American Heritage Month has come off and on to our country since 1990 and has its own website: http://nativeamericanheritagemonth.gov.

President Obama wrote in his declaration, “During National Native American Heritage Month, we recognize their many accomplishments, contributions, and sacrifices, and we pay tribute to their participation in all aspects of American society.”

Our society needs children’s books about the American Indians. Books about what happened in the past, biographies of American Indians, and all the ways American Indians contribute now.

But the last thing I think any children’s author would want is to have their story listed as a book that is not recommended and is deemed harmful to the well-being of children, including American Indian children. According to a 2008 article on the Poverty & Race Research Council site, there are today in these United States, 560 federally recognized American Indian tribes, approximately four million people, and 42% of these American Indians are under the age of nineteen. These numbers do not include what must be in the tens of thousands, people such as myself of Native American descent but raised within another culture and not belonging to a tribe.

The Oyate organization defines itself, according to their website (www.oyate.org), as “a Native organization working to see that our lives and histories are portrayed honestly, and so that all people will know our stories belong to us.” Oyate conducts critical evaluations of books and curricula that contain “Indian themes” and it also conducts workshops, has a reference library and distributes materials, especially that written by Native people. Oyate is the Dakota word for ‘people’, says the website. Oyate maintains a list of not recommended children’s books.

Eight of the twenty-eight worst books on Oyate’s books to avoid list were published in 2005 and after. Among the authors on the list of twenty-eight books: Janet Heller, Ann Rinaldi, Cynthia Rylant and Kathy Jo Wargin. Among the titles: I Am Apache, Touching Spirit Bear, and D is for Drum: A Native American Alphabet.

Debbie Reese, tribally enrolled in the Nambe Pueblo and a professor in the American Indian Studies program at University of Illinois at

Joseph Bruchac’s The Arrow Over the Door takes place in 1777 near Saratoga, New York. The Americans have begun their war of rebellion and the Quakers desire to remain neutral and peaceful while the Abenaki Indians must decide if they are going to answer King George’s call to fight the Rebels.

And so Bruchac tells the story of the historical Easton Meeting that occurred at a Quaker Meetinghouse in Easton, New York (not far from Saratoga) between a group of American Indians and the Friends that worshipped in the Meetinghouse.

The story is told in alternating viewpoints between two young teenaged boys: Samuel, a Quaker and Stands Straight, an Abenaki.

The Arrow Over the Door is a very short primary grade historical fiction, that could easily be read aloud to ages six and up. My guess is that the very upper end of readership on this piece to be about ten. And I was disappointed in that respect. It is an exciting, interesting story about two well-realized characters and so much more could have been done with this story to make its appeal to include the age of child the characters are, fourteen or so. I have seen this book recommended for higher grades, but I disagree. It is fairly simplistic and plot-oriented.

In the book, we learn that our custom of shaking hands upon meeting someone derives from the Quaker tradition of extending a hand of friendship. But, extending a hand for a handshake denotes equality between the two parties and so sometimes, the hand in Colonial times was rejected.

We learn that the Abenaki’s called the Americans “Bostoniaks”, the English “Songlismoniaks”, and the French “Platzmoniak”, that Elder Brother Sun “liked the sight of war”, and to say thanks in Abenaki we would say “wliwini”. Stands Straight at the age of eight, swam down to the bottom of a cold, icy river to grasp what he could and came up with a seeing stone. The Shawnee seemed to also have this custom amongst their boys.

I will not tell you what happens when the Abenaki warriors come upon the meetinghouse as they search for the enemy, the Bostoniaks. Bruchac does a wonderful job with building the suspense through the voices of the two boys, both of them concerned for their lives and their loved ones.

The Arrow Over the Door is an excellent choice for the study of American History in grades one to three as Bruchac is faithful to represent both sides of the story, the European and the Indigenous. It was published in 1998 by Dial Books for Young Readers and includes fine pencil illustrations by James Watling. My boys would’ve enjoyed this book a great deal, and I would also include it on a list for older dyslexic readers, as its pace is excellent, the story compelling and the reading easy but not patronizing.

Through Indian Eyes – The Native Experience in Books for Children was published in 1998 by Oyate and edited by Beverly Slapin and Doris Seale.

This is a must read book for children’s writers/illustrators, educators and librarians. Through Indian Eyes begins with a series of essays by such notables as Joseph Bruchac, Doris Seale and Beth Brant on how American Indians view what is written about them, how they view what has happened to them (and continues to happen), and how racism against the American Indian is very alive and well today and occurring quite frequently, in of all places that it shouldn’t, books for children.

In the midst of the essays are poems written by American Indians that will not only help to open your eyes but will touch your heart. The book then includes 91 (large print) pages of reviews by Slapin and Seale of children’s books that include the presence of American Indians in them. Recommended and not recommended books are included and this is followed by clear cut examples of what should not happen in a children’s book along with what should. For example, “Look at Picture Books” asks is E for Eskimo, are Indians counted, do the Indians have ridiculous names?

The reader is given several and numerous examples in published pieces in which all concerned should “look for stereotypes, loaded words, tokenism, distortion of history, lifestyles (the myth of the vanished Indian), dialogue, standards of success (how are modern Indians portrayed?), the role of women, the role of elders, the effects on a child’s self-esteem, and the author or illustrator’s background.

The following is a partial list of recommended books that I’ve included on my reading list. I have been reading a lot of the books that are not recommended and it is time for me to continue reading what is:

- Halfbreed by Maria Campbell (adult)

- Children of the Maya

- Morning Star, Black Sun

- To Live in Two Worlds all by Brent Ashabranner

- The Mishoni Book by Edward Benton-Banai

- A Legend from Crazy Horse Clan by Moses Nelson Big Crow

- Night Flying Woman by Ignatia Broker

- Columbus Day by Jimmie Durham

- Death of the Iron Horse

- Star Boy both by Paul Goble

- Native American Cookbook by Edna Henry

- A Thousand Years of American Indian Storytelling by Jeanette Henry

- American Indian Stereotypes in the World of Children by Arlene Hirschfelder (adult)

- The Ways of My Grandmothers by Beverly Hungry Wolf

- This Song Remembers by Jane Katz

- How the Birds Got Their Colours by Basil Johnston

- Sparrow Hawk by Meridel Le Sueur

- Native American Testimony – A Chronicle of Indian-White Relations from Prophecy to the Present, 1492-1992 edited by Peter Nabakov (adult)

- Who-Paddled-Backward-With-Trout by Howard Norman

- Legends of Our Nation by North American Indian Travelling College

- The People Shall Continue by Simon Ortiz

- The Story of Jumping Mouse by John Steptoe

Some of the books above are by white authors and Slapin and Seale state repeatedly that it is not the author’s ethnicity that matters as much as it is her handling of the material, the characters, the historical background, etc. We should not be writing books that hurt children and we are responsible for being aware of racism against the American Indian in our work.

Oyate published in 2005 another book edited by Slapin and Seale titled A Broken Flute – The Native Experience in Books for Children. I have a copy but have not read it yet. It looks like a wealth of further information and understandings of how American Indians are treated in children’s literature with, of course, reviews on books written since 1998.

Please educate yourself as to how our society is continuing to perpetuate racism against the American Indian through children’s literature, whether we are using books published decades ago or books published this year. Be very careful if you are a homeschool parent. Many outright racist books are recommended in homeschool book catalogues and curriculums, books such as The Matchlock Gun.

What disturbs me the most, is these are most-often Christian institutions or businesses profiting off the continued glorification of our country’s past sins against our Indigenous peoples. But if we all stopped buying these types of books for our children, they would be forced to quit printing them.

And if you as a children’s writer are not taking this seriously yet, look on this list from Oyate and see if you know any of these writers and decide if you want to end up on this list also : http://www.oyate.org/books-to-avoid/index.html

By:

Jennifer Porter,

on 4/27/2009

Blog:

Post-Its from a Parallel Universe

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's books,

YA Book Review,

Pocahontas,

MG Historical fiction,

Native Americans in Children's Books,

Powhatan People,

Captain John Smith,

History,

Native Americans,

YA Books,

Add a tag

Pocahontas is an excellent historical fiction read for ages ten and up. Bruchac did his work in researching and writing this 147 page book that dispels many of the Disneyfied myths of Pocahontas and John Smith.

Pocahontas is told by both the eleven-year-old Powhatan girl, daughter of the Great Chief or Mamanatowic, of the Powhatan people and Captain John Smith of England. The story covers the time from the voyage to the scene in Mamanatowic’s village, in which John Smith misinterpreted what had happened and thinks he was saved by Pocahontas.

Pocahontas is her everyday name. Mataoka is the name only her closest friends and family use. And Amonute is her formal name, a name meaning favored one and a name she will no longer be known by when her father passes on. She lives in the village Werowocomoco with her father. Her mother died but her father’s sisters care for her. Her mother would not have lived in the same town as her daughter, but rather with her own family.

The Tassantassuk, or Outsiders, have arrived on the shores of Chesepiock, the great salt bay, in their big swan canoes and are building a camp in one of the worst and most foolish places to try and live. John Smith has been on board the Susan Constant as a prisoner but is released when his name is read as one of the leaders on the council.

The story then follows the two cultures as they clash against each other and learn about each other. The Powhatans keep the English alive despite the English being offensive, rude and hostile (not to mention aggressive and violent).

Mamanatowick destroyed the Chesepiock people because of a prophecy that foretold that a great nation would rise from the Great Salt Water Bay and bring an end to Mamanatowic’s kingdom. So, he made war on them and the Piankatanks and then attacked and removed the Kecough people from their land. Now, a new threat, a more dangerous threat with their powerful thunder sticks, has cropped up.

Pocahontas never meets John Smith until his capture by her Uncle and the ceremony in which her father adopts him as one of his own sons. She never goes to the white man’s camp without her father’s permission and with escorts. Mamanatowic thinks the ceremony has obligated John Smith to honor the Powhatan leader.

Captain Smith has his hands full getting the lazy men to work and to protect themselves and recover from assundry illnesses. He also engages in some political take overs and expeditions into the surrounding country. He is not captured until Dec. 1607 (they landed in April 1607). The Powhatan call him Little Red-Haired Warrior and he earns their respect with his courage and fighting skills.

We learn what it must have been like for both of them to be who they were and to live when they did. We learn that the Powhatan recognized five seasons: Cattapeuk (spring), Cohattayough (early summer), Nepinough (late summer), Taquitock (fall) and Cohonk (winter). “Everyone knows the earth prefers the touch of a woman’s hands,” Pcoahontas is told while she helps the resting women during their time in the Moon House.

When Smith is captured, Pocahontas hopes that he will join her people and help them get rid of the worthless and rude Tassantassuk. Smith lies to Mamanatowic about why the English are there and how they even ended up there. Pocahontas impulsively rushes forth when Smith’s head is lain upon the rocks in order to be the first to touch him so that she’ll always be the first of his relatives among her people.

When Smith returns to Jamestown, he is arrested and charged (but acquitted) for the deaths of the other men on the expedition up the Chickahominy River, in which he was captured. In September 1609, he is badly injured (possibly intentionally) and then someone attempts to assasinate him while he recovers. Pocahontas has become a frequent visitor and when he returns to England in October, she is told that he died.

Brucac includes in the end both a section on Early 17th Century English and the Powhatan Language. The author used all of Smith’s accounts in his research and also accounts of others. He gives us selected words and phrases in Powhatan, place names and Native names.

How to count to ten in Powhatan:

- necut

- ningh

- nuss

- yowgh

- paranske

- comotinch

- toppawass

- nusswash

- kekatawgh

- kaskeke

Bruchac primarily based his Native stories (of which preface Pocahontas’s chapters) on Powhatan and eastern Algonquin traditions and the works of Helen C. Rountree, in particular her 1989 book The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture. He also had the help of Native Americans and the Powhatan’s and his own familiarity with the Abenaki language.

All of us have two ears; our Creator wishes us to remember there are two sides to every story, says Bruchac.

If you get the chance, visit the historic site of Jamestown. It is a fascinating trip. The fort was actually very small and built in a triangle and right on the river’s shore. It is definitely in the midst of a swamp.

By:

Jennifer Porter,

on 4/20/2009

Blog:

Post-Its from a Parallel Universe

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Squanto,

Patuxet,

Wampanoag,

Pilgrims,

Children's books,

History,

Native Americans,

MG Historical fiction,

Native Americans in Children's Books,

First Thanksgiving,

Add a tag

Looking for the Native American perspective on the first Thanksgiving? Joseph Bruchac’s Picture Book Squanto’s Journey accomplishes this while leaving the readers remindful of giving thanks. This book is appropriate for any age child.

The book is wonderfully illustrated by Greg Shed. Squanto tells his story in first person. Born in 1590 and of the Patuxet people, Squanto is taken against his will to Spain in 1614. He returns to his homeland in 1621.

The Patuxet are the People of the Falls and when Squanto journeys home with a friend of John Smith’s in 1619, he is told that most of the Patuxet have perished in a great illness. Squanto’s entire family have died. Thousands of Pokanoket have perished also and they are still weak from the illness. They capture Squanto and he becomes involved with the Pilgrims. Massasoit, a sachem of the Potakonet, is wary of befriending the English.

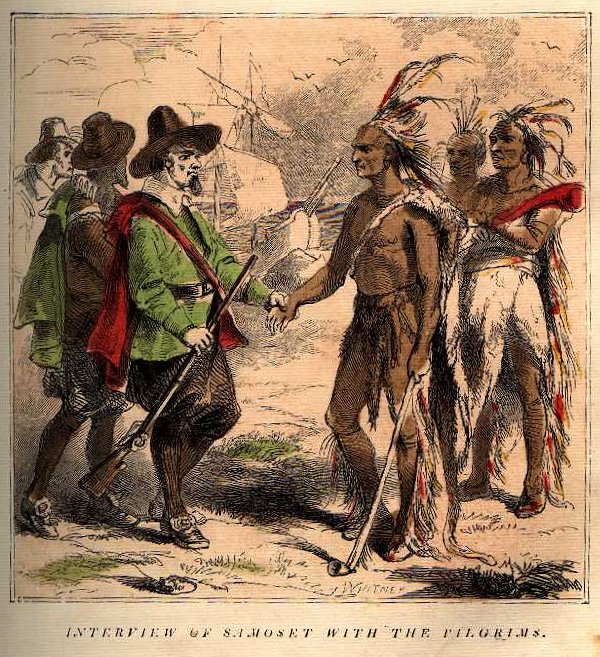

Samoset, a sachem of the Pemaquid people, walks into Plymouth on 16 MAR 1621 and returns on 22 March with someone who can speak English — Squanto. Plymouth was once Patuxet, Squanto’s village.

Squanto is freed by the Pokanoket and he begins teaching the Pilgrims how to survive in America. “Together we might make our home on this land given to us by the Creator of All Things.”

A good harvest comes in in the Fall and Squanto gives thanks and hopes for many more days to give thanks for. He gives thanks for the people.

In Bruchac’s author’s note, he explains how carefully he researches and learns the stories of the Native Americans he tells. Squanto’s Journey was published in 2000 by Harcourt Books.

By:

Jennifer Porter,

on 4/10/2009

Blog:

Post-Its from a Parallel Universe

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Native Americans,

YA Books,

Sonlight Curriculum,

MG Historical fiction,

Native Americans in Children's Books,

Shawnee Indians,

Children's books,

Family,

History,

Add a tag

It appears that I’ve finally truly gotten the attention of the folks over at Sonlight Curriculum: http://www.sonlightblog.com/2009/04/questionable-content.html.

But it appears their answer to american history books with negative and/or inaccurate portrayals of Native Americans and the treatment of Native Americans by whites is to put an oft-overlooked warning comment in a teacher’s guide rather than doing the work to find better books.

My husband, bless his English-German soul, came up with a much better analogy. He likened the children reading the books, or hearing them read-aloud, to a jury. The prosecuting attorney is the author of the poorly written book. The teacher is the defense attorney and the defendants are the American Indians.

The jury hears a passage presented by the prosecutor that American Indians were vicious, aggressive and without cause (they are reading Matchlock Gun, for example). Suddenly, the defense jumps up and whips out their teacher guide (if they remember) and shouts, “Stop! The American Indians were protecting their homes. Treaties had been made that whites ignored. Frontier people knew they were encroaching on Indian lands and they did so with the government’s backing.”

The judge turns to the jury and says, “Please disregard that passage the prosecutor just read. Go on, Prosecutor, and continue your argument.”

The prosecutor smiles slyly and continues reading the riveting, informative and engrossing literature while the American Indian sits in her chair with no voice. The jury, being children, are engrossed with the story and have completely forgotten the defense’s sermon. The jury, being children, are riveted by the images their minds are creating as they read the story and those images stay with them for a very long time, if not forever. Especially, since the defense is always harping on them to do their chores, to stop hitting their sibling, to brush their teeth and get to bed, to learn their multiplication tables and now not to listen to everything in the book they read to learn what really happened in American history.

I started on this journey as my daughter and I began reading the historical fiction assigned to us through the Sonlight Curriculum’s American History 3/4 program. I made sure to back up Bulla’s Pocohontas book with a selection of others, including nonfiction as Bulla’s book does the Disneyfied version of Pocohontas. I also was careful about presenting the first Thanksgiving. But, after reading Caddie Woodlawn, Matchlock Gun and Skippack School (amongst others) my daughter said to me, and I do quote her, “I am sick and tired of these terrible books about these so-called mean Indians. I want to read a book that is told by an Indian child. Not all Indians were bad and besides, the whites were stealing their land.”

And so since she was right, and I was sick of them also, we began our search. And, we are still searching. We have found some excellent resources, including Debbie Reese’s blog and Cynthia Leitich’s website.

So, why should we care if Sonlight has children reading “terrible books” as my daughter calls them. Well, we care because both of my great-great grandparents were mixed blood. And we care because we are Christians and God calls us to be truthful, honest and compassionate to and about all of the people He created. We care because American Indians are still suffering as a result of the actions our white ancestors enacted upon them. We care because we care about children, whether they be white or Asian or black or Indian.

Why wouldn’t Sonlight worry that one, just one, of the children being taught American history through their curriculum might be American Indian?

Sonlight is using primarily books that were published years ago, some of them decades ago. If you look closely, they are primarily Newberry award winners; as if that makes them instantly okay. I think if Sonlight did the work, and they could have done it this past year, they could come up with a much better curriculum. But I got my new catalogue and I see none of the books have changed. And so I threw it out.

I think it is our God-given responsibility to educate ourselves as to what really happened in American history and to honor God by teaching our children the truth, whether we use historical fiction, nonfiction or textbooks.

I am 45 years old, and I just learned that Thomas Jefferson, whom I’d always admired, had a fervent policy to wipe out the Shawnee Indian, not just remove them. He wanted them dead and gone. He authorized giving them disease-infested blankets. He speculated in Indian lands.

The President I’d admired tried to wipe out my ancestors and I never knew it until I read Colin Galloway’s book The Shawnees and the War for America. This is not something I should have found out on my own, after all I was an AP student in American History and graduated from college.

Crossing the Panther’s Path was written by Elizabeth Alder and published in 2002. It is the fictionalized story of a fifteen-year-old boy named Billy Calder and his involvement with the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh during the War of 1812.

The character of Billy Calder, according to the author, is based upon the life of Billy Caldwell, who eventually became named a Pottawattamie Chief. If you research Billy Caldwell on the internet he will be listed as having a Mohawk mother, a Pottawattamie mother and even a Shawnee mother but Alder calls his mother Windswept Water, of the Mohawk tribe. His father was an Irish man and a captain in the British army and in the novel his father is loving and kind. According to most information I found, his father abandoned him as a young child and Billy grew up with his mother’s tribe. His father took Billy in later in his childhood and had him educated. His father eventually disinherited Billy and it appears to have been due to conflicts over their both desiring to be Commandants of the Canadian fort in Amherstberg, across from Detroit, Michigan.

The novel is also inaccurate in its recounting of Billy’s wives and so it makes sense that the character’s name was changed, though most other historical figures retain their real life names.

Billy wants to join Tecumseh in his fight against the Americans and their theft of Native lands, against his mother’s wishes. Billy is aptozi meaning half-breed. In the end, he marries Jane, another person of mixed-blood. I enjoyed this aspect of the novel. My great-great-grandfather Millen Ralston was half Scotch Irish and half, well, we’re not totally sure. Possibly Cherokee, most likely Shawnee. Millen married Eliza Sinkey who was of mixed blood also, Shawnee, maybe? Some cousins say her ancestors - the Greens, the Hustons, the Sinkeys - were associated with Blue Jacket’s tribe. Some cousins say some cousins today still know some Shawnee language, passed down through the generations. And we have all spent countless hours trying to document or prove our ancestry. Some cousins have done DNA testing to prove their Native American ancestry. I think it is going to remain an educated guess.

I also think we need to talk about the American experience of being mixed blood more often. The story of my ancestors is the story of America also. Survival through assimilation. When Jane doesn’t want Billy to fight anymore, I think my great-great-grandmother may have spoken those words.

Tecumseh is a powerful, intelligent, heroic character in this novel. Tecumseh says it is time for war when a great sign in the sky is followed by the ground shaking. A greenish light then streaks across the sky as when he was born and named Panther Passing Across. Tecumseh shortly after stomps his foot and creates an earthquake felt even by President Madison. Tecumseh is articulate and charismatic.

The fight the Indians waged in an attempt to stop the Americans is presented realistically. Nothing is left out to present a different picture. The massacre at Fort Dearborn by the Native Americans is relayed in its horrifying detail as is the ruthlessness of William Henry Harrison in his pursuit of extermination of the American Indian. As is the deception the Americans pulled at Fort Dearborn, promising whiskey and ammunition they’d already dumped in the Detroit River, for safe passage out of defeated Fort Dearborn. And it is for these reasons, that I recommend this book for middle grade and above students of American history.

I do have some issues with Alder’s novel. Tenskwatawa is portrayed as an imbecilic alcoholic, at constant odds with his brother Tecumseh. Tecumseh does not even really believe that Tenskwatawa really had a vision from Grandmother Kokomothena, telling him that he is the spiritual leader she raises up in difficult times to lead others on the right path. Tenskwatawa is only interested in drinking and he cruelly harasses young children, scaring them with his knife into Billy’s arms. Tecumseh almost kills his brother when he returns and discovers that Tenskwatawa had battled with Harrison, resulting in the destruction of Tippecanoe. I cannot quote my sources but after much reading I had come to believe that Tenskwatawa had given up alcohol and this portrayal bothered me. It felt like a huge liberty to use Tenkswatawa’s real name and identity when Billy Calder’s had been changed. Tecumseh and his brother were very close, they built towns together.

Alder also claims in the novel that Tecumseh traveled to the Blackfoot and possibly the Sioux in his quest to build a coalition. That horse and rider swam across the Detroit River from Fort Malden to Amherstberg yet the current of the river was so swift it hardly ever froze over. That Tecumseh’s son, Cat Pouncing, and Billy are able to bury Tecumseh according to Shawnee custom, his face painted and his head to the West. That a genuine warmth was rarely accorded to outsiders by the Shawnee.

My reading on Shawnee history is not what it should be, but my impression is that the Shawnee often took in outsiders. That what made you Shawnee was the following of their customs and traditions and way of life rather than the color of your skin. That they adopted people willingly and warmly into their tribe.

I cannot imagine swimming across the Detroit River, it is ½ mile wide. The current runs fast, even on a horse. I could not find this information, as to whether or not they travelled across this way. Maybe the river has changed over time.

I have read that Tecumseh’s body was not ever identified, that no one knows where he was buried. That he was probably so badly mutilated no one could identify him. I rather think this is probably the case as he caused the Americans untold grief.

I have located a source that says Tecumseh met with the Sioux, but have not found one to say he traveled to Montana. If you can clear this up for me with a source, I would appreciate it.

Despite some of the dialogue being forced and irritating at times, the story is well-paced and holds the reader’s interest. I will have my daughter read Crossing the Panther’s Path when we study the War of 1812. We will discuss whether or not it is fair to portray Tenskwatawa as a drunk, when he had reformed himself. And by the way, my Ralston ancestors fought in the War of 1812 and for the Americans.

Marguerite de Angeli had The Skippack School published in 1939. It is one of the readers in the Sonlight Curriculum’s elementary American history program. I feel it should be removed from the curriculum due to its inaccurate and stereotypical portrayal of American Indians. This reader comes after a series of books told from the white settler’s point of view.

This is unfortunate because if the references to American Indians were edited it would be a nice little story about the Germans who settled in Penn’s Woods in Pennsylvania about 1750 to worship God in their own way. The Indian characters do not advance the story nor enhance the story and are treated as part of the setting.

The Skippack School is the story of the Shrawder family - Pop, Mom, little sisters and Eli. I would guess that Eli is about nine years old, but it is not made clear in the book. The German Shrawder’s settle near German Town and Eli attends Skippack School two to three days a week. He can already speak English though he had just walked off the boat. Eli is a troublemaker, but because of kind, gentle, and patient schoolmaster Christopher Dock, he begins to study and read his verses.

Eli misses school the day he is to read the Scriptures aloud (a big honor) as his mother is away caring for ill neighbors. An American Indian stops by and demands to be fed. He is a Leni-Lenape. He uses words like “Ugh” and eats like a pig. White Eagle makes a comment about Indians owning the land. It is not an accurate portrayal or even semi-realistic.

Eli must sell his handmade bench to replace the glass window he broke at school and Dock takes him to German Town for his first time there. There is a very good description of visiting the printer, if you are also reading about Ben Franklin this description enhances your other readings. There is also a scene of Indian men eating in the village square and being served by village women. Eli is told, “No child need fear the Indians here. They’ve never broken the Penn Treaty.” But the settlers farther west are “having trouble” because the Indians are forming a council to address their issues. Too bad de Angeli couldn’t have recognized it wasn’t the Indians we needed to worry about when it came to honoring a treaty.

Eli learns so much in town, that he arrives home and makes his own little book for Dock complete with a printed wood block design on the cover and colored illustrations. Master Christopher then presents Eli with a beautiful painting with a Scripture and the alphabet. I enjoyed the character of Master Christopher, if only all teachers were like him.

German Town is a neighborhood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Here is a website where you can go if your ancestors settled in German Town. http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~original13/

Marguerite de Angeli http://www.deangeli.lapeer.org/Life/index.html was born in Lapeer, Michigan in 1889 and won the Newberry Award in 1949 for Door in the Wall. In 1902, she moved with her family to Pennsylvania. When I lived in Metamora and took my young sons to the Marguerite de Angeli Library in Lapeer I would always feel sad as I drove a block or two north on M-24 and saw the For Sale sign in front of de Angeli’s Lapeer home. There is a marker denoting the house. I hope someone bought that house and preserved it.

The Leni-Lenapes are called Delaware http://www.delawareindians.com/ and despite the Penn Treaty, their lands were taken from them and they were forced west to Ohio and continuing westward to Indiana. Some of the Delaware sided with Tecumseh and the British and fought against the encroachments of the Americans. http://www.munseedelawareindiannation-usa.us/page06.html

The Shawnee often lived with the Delaware and it is for this reason, that some of my ancestors may have been Delaware as we will never be able to prove for certain my ancestor’s tribal identity. They married caucasians and assimilated into white society and we are left with oral history only.

The Delaware were forced onto reservations in Oklahoma.

In Noblesville, Indiana (about 45 minutes north of Indianapolis), you can visit the Strawtown Koteewi Park which used to be a Delaware village in the early 1800’s. The village rested against the shores of the White River. We visited this park and met very friendly and informative archaeologists and park rangers.

http://www.co.hamilton.in.us/parks_details.asp?id=2932

Also in Noblesville is the Conner Prairie Living History Museum http://www.connerprairie.org/

This is a wonderful field trip for homeschool families. There are several historic buildings on site and a recreated Delaware Indian village. A Delaware gentleman was on hand and kindly showed me the garden with corn growing from seed passed down through the generations. He explained that they plant the corn in a circle and when the seedlings are several inches high, they plant pole beans in an outer circle. The pole beans then grow around the corn. The corn was at least twelve feet high. He also showed my daughter a Delaware game played with sticks.

On site we also saw a Civil War reenactor and buildings hosted by costumed interpreters. One of my daughter’s favorite stops was a petting barn where many of the farm animals were not in their pens! The young cow simply rested on the barn floor and enjoyed having her muzzle petted.

If you do read The Skippack School, please supplement with trips such as I described above and with readings about the Delaware Indian. Please try to give your children as much of the whole story as possible.

Colors of War by Pat Beckman is an MG historical fiction novel about the War of 1812 with a focus on the Shawnees involvement and the death of Tecumseh. It centers on a pre-teen boy Michael, an orphan being raised by an older brother and an abusive nasty uncle, who runs away from home and is adopted by Tecumseh’s older sister Star Watcher and Tecumseh. The story takes place around Detroit, Michigan, Lake Erie, and the Shawnee encampment on Bois Blanc Island in the Detroit River.

Tecumseh was an intelligent and visionary war chief of the Shawnee Indians who gave his life in an attempt to pull the Indian nations together and stop the European Americans from continuously stealing their lands.

If you haven’t figured this out yet, Tecumseh is one of my heroes. My Shawnee ancestors did not go to the reservations and lived in Western Pennsylvania and Ohio, our family records indicate they also spent time in West Virginia. They inter-married with Scots-Irish and assimilated into white society.

My great-grandfather was the son of two mixed-race people, both of whom had an Indian mother and a white father. But my grandfather, who could have told me all about this, died in 1939. He married my 100% Irish grandmother and she did her best to remember what she could. Which was mostly about being Irish and how much I reminded her of her own mother– the one who left Ireland on her own at the age of 18 with two brass candlesticks and a lot of courage.

So, we have been on a quest to read children’s books about the Shawnees, told from their perspective. Colors of War does not meet that criteria. There are spots that made me wince. Michael describes the War Dance as an “awful noise”, “whooping and bellowing”, “high-pitched shrieks on the Stomp Ground”. Tecumseh picks Michael of all the young men to go with him and talk to the British about their plans of war against the Americans. Michael thinks of himself as more capable and smarter than the other Indians. He has magic, since he can draw pictures with charcoal on bark. I am not certain that this newness of seeing someone draw would be accurate, that no Shawnee ever before 1812 figured out how to draw pictures. Ernest Spybuck was a renowned Shawnee artist, painting scenes of Indian life not many decades later.

Michael even takes charge of the Shawnee scouts at old Fort Miamis during the battle, telling them what to do. That they need to tell Tecumseh about the Americans movements as if the grown scouts couldn’t have thought of this themselves.

Michael’s older brother Davey fights with the Americans and the two brothers are re-united in the end. Tecumseh leaves Michael an “I love you like a son” letter at the abandonned Bois Blanc camp and we are left to think of Tecumseh’s spirit as a sparkling glittering star that shoots across the heavens. Tecumseh means “panther passing across” as Tecumseh’s father saw a comet when his son was born.

There is a glossary of Shawnee words and their meanings in English as they are used throughout the book and an interesting description of Michael having his ears cut to create loops of skin to hang pendants from, in the tradition of the Shawnee. And an interesting use of the terminology for all of the moon cycles: Moon of the White Snows, Moon of the Sugar Weather, Moon of the Flowers, Moon of the Berry, Moon of Green Corn, Moon of Fallen Leaves.

The Courage of Sarah Noble was written by Alice Dalgliesh and published by Atheneum Books for Young Readers in 1954. It is a Newberry Honor Book — historical fiction for ages 6 and up. Illustrations by Leonard Weisgard.

Dalgliesh based the story upon true facts. Eight-year-old Sarah Noble travels with her father in 1707 to the Connecticut wilderness to cook for him while he builds their new house. Faced with meeting wild animals and Indians, Sarah must keep up her courage.

When Father leaves to bring the rest of the family to their new home, Sarah remains behind in the home of Native American Tall John and his family. They care for her, even making her deerskin clothes and moccasins, and Sarah learns they are a loving and kind people. When her father returns with the family, Sarah can hang up her cloak and relax a little about keeping up her courage.

I did not have any issues with this book and how it presented the need for this child to have courage. I pictured her as growing up prior in a colonial town, sheltered in a fairly settled community, without the experience of being exposed to the wilderness and the animals that live there. Some of it may be a stretch on the author’s part but the fear of Indians would not be.

As for both Sarah and Father worrying about leaving her with Tall John, that felt right and normal to me irregardless of Tall John’s ethnicity or race or his prior behavior. I worry whenever I leave my children, even when I know the people. Things go on behind closed doors and have for all of mankind’s history.

Indians did battle between tribes and some Indian tribes were cruel to their captured prisoners. Sarah worries about the Northern tribe coming down to Tall John’s place. Ignornance amongst white people as to the nature of the Native Americans was the norm. How would Sarah know anything other than to be afraid, as her mother has raised her to be so? What the book shows is how our stereotypes are so often wrong. Sarah worries when the Indian children come to visit her, only to find out they mean no harm.

How many people are afraid of what will happen if Obama becomes President simply because of the color of his skin?

A more interesting note would be to find out how Sarah Noble viewed the Indians the rest of her life and what she taught her children and grandchildren about them.

I did wonder where the rest of Tall John’s people were and who they were – I don’t remember hearing what tribe they are. It seemed unsual for them to be there all alone. But the general gist of the book, that we can befriend each other despite our differences is a valuable one.

Overall, this is a delightful and easy to read book of 55 pages in 11 chapters. The dangers of the wilderness are explored but never brought forth in a frightening manner for the reader. Sarah’s Christianity and Tall John’s differences are treated with respect and dignity. Despite having been written 54 years ago, my ten-year-old enjoyed reading it aloud to me.

Thanks for this informative post Jennifer. Recently, I was involved in a research project on First Nations here in Alberta, and it was an eye-opener for me. This book you’re recommending sounds like a great read.