new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: bilingual education, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: bilingual education in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

jilleisenberg14,

on 7/1/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading Aloud,

parents,

Educators,

bilingual education,

reading comprehension,

hispanic heritage,

Educator Resources,

Latino/Hispanic/Mexican,

dual language,

ELA common core standards,

ELL/ESL and Bilingual Books,

Add a tag

Peggy McLeod, Ed. D. is Deputy Vice President of Education and Workforce Development at the National Council of La Raza (NCLR).

Today we are featuring one of First Book’s celebrity blog series. Each month First Book connects with influential voices who share a belief in the power of literacy, and who have worked with First Book to curate a unique collection that inspires a love of reading and learning. All recommended books are available at deeply discounted prices on the First Book Marketplace to educators and programs serving children in need. Peggy McLeod, Ed. D. the Deputy Vice President of Education and Workforce Development at the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), writes on engaging Latino families and children in reading and learning.

Today we are featuring one of First Book’s celebrity blog series. Each month First Book connects with influential voices who share a belief in the power of literacy, and who have worked with First Book to curate a unique collection that inspires a love of reading and learning. All recommended books are available at deeply discounted prices on the First Book Marketplace to educators and programs serving children in need. Peggy McLeod, Ed. D. the Deputy Vice President of Education and Workforce Development at the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), writes on engaging Latino families and children in reading and learning.

Any student who has parents that understand the journey from preschool to college is better equipped to navigate the road to long-term student success. While parent engagement is critical to increasing educational attainment for all children, engaging Latino parents in their children’s schooling has typically been challenging – often for linguistic and cultural reasons.

The National Council of La Raza’s (NCLR) parent engagement program is designed to eliminate these challenges and create strong connections between schools, parents, and their children. A bilingual curriculum designed to be administered by school staff, the Padres Comprometidos program empowers Latino parents who haven’t typically been connected to their children’s school. Many of the parents the program reaches are low-income, Spanish-speaking, first and second generation immigrants. Through Padres Comprometidos, these parents gain a deeper understanding of what the journey to academic success will be like, and how they can play a role in preparing their children for higher education. Prior to participating in the program, not all parents expected their children to attend college. After the program, 100% of parents indicated that they expected their children to attend college.

Much of Padres Comprometidos success rests on the program’s ability to address language and culture as assets, rather than as obstacles to be overcome. This asset building strategy extends to NCLR’s partnership with First Book. Together, we’re working to ensure Latino children of all ages have access to books that are culturally and linguistically relevant, books they need to become enthusiastic readers inside and outside of the classroom. Click here to access the three parent engagement curricula developed by NCLR—tailored to parents of preschool, elementary and secondary school students.

Below you will find a few tips and titles that can help you engage families and get children – and their parents and caregivers – reading and learning.

La Llorona

1. Find ways to connect stories that parents know about to help them engage in reading and conversation with their children. This Mexican folktale can open that door: La Llorona .

Spanish-English Dictionary

2. Keep an English/Spanish dictionary handy to use when you have a parent visiting or to give away to a parent or caregiver who needs it. It will show them that you’re making an effort to engage in their language of comfort, such as Webster’s Everyday Spanish-English Dictionary.

The Storyteller’s Candle

3. Learn about the children you serve and their heritage, and identify books that will affirm them. This Pura Belpré award winner is actually about Pura Belpré, the first Latina (Puerto Rican) to head a public library system: The Storyteller’s Candle.

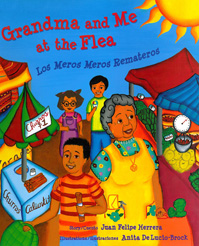

Grandma and Me at the Flea

4. Share books that include some of the everyday experiences of the children and neighborhoods you serve, like this story highlighting the value of community and family: Grandma and Me at the Flea.

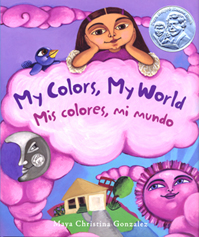

My Colors, My World

5. Bilingual books provide family members and caregivers the opportunity to read the same books their children are reading, but in their language of comfort. Families will love reading about all the colors of the rainbow in English and Spanish: My Colors My World.

Sign up with First Book to access these and other great titles on the First Book Marketplace.

Filed under:

Educator Resources,

ELL/ESL and Bilingual Books Tagged:

bilingual education,

dual language,

Educators,

ELA common core standards,

hispanic heritage,

Latino/Hispanic/Mexican,

parents,

Reading Aloud,

reading comprehension

By:

Hannah,

on 4/12/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Latino/Hispanic/Mexican,

Día de los niños/Día de los libros,

Curriculum Corner,

English-Spanish,

libros en Español,

Reading Aloud,

parents,

bilingual books,

Read Aloud,

guest blogger,

ell,

bilingual,

teaching resources,

bilingual education,

reading comprehension,

Add a tag

Jennifer Brunk has been teaching Spanish and English learners from preschool to university level for over 20 years. She re sides in Wisconsin where she raised her three children speaking Spanish and English. Jennifer blogs about resources for teaching Spanish to children on Spanish Playground. The following post is reprinted with permission from her original post at Spanish Playground.

sides in Wisconsin where she raised her three children speaking Spanish and English. Jennifer blogs about resources for teaching Spanish to children on Spanish Playground. The following post is reprinted with permission from her original post at Spanish Playground.

Research has shown that reading to children helps them learn vocabulary and improves listening comprehension skills. As a parent or teacher, you are probably convinced of the value of reading to your child in Spanish, but how should you do it to promote language development?

First, it is important to keep in mind that above all reading should be enjoyable. We want to create positive associations with reading in any language. So, use these strategies and add plenty of silliness, snuggling, or whatever makes your child smile.

1. Identify core vocabulary in the story. If there are words that are central to the story that your child does not know, teach them first or make them clear as you read by pointing to the illustrations or using objects.

2. Use illustrations, objects, gestures and facial expressions to help kids understand new words. Choose stories with a limited number of new vocabulary words and a close text-to-picture correspondence.

3. Simplify the story if necessary. It is fine to reword or skip words or sentences. As your child becomes familiar with the story and acquires more vocabulary, you can include new language.

4. Read slowly. Children need time to process the sounds, connect them with the illustrations and form their own mental images.

5. Pronounce words as correctly as possible. To develop listening comprehension skills and learn new vocabulary, children need to hear correct pronunciation and natural rhythm. If your Spanish pronunciation is a work in progress, take advantage of technology. Look for books with audio CDs and ask a native speaker to record stories. At first, listen to the story with your child and take over reading when you are confident of the pronunciation.

6. Engage your child with the story by providing different ways for her to participate.Ask questions that can be answered by pointing or say a repeated phrase together. You can also give your child a toy or object that she can hold up each time she hears a key word.

7. Read the same story over and over. Repetition is essential to language learning.

8. Relate the story to your child’s life by drawing parallels as you read: Tiene un perro. Nosotros también tenemos un perro. As you go about your daily routines, refer to stories you have read.

9. Use puppets or figures to act out stories when you are playing with your child. Dramatizing the story adds movement to enhance learning and provides essential repetition of the language in context.

10. Do activities that expand on the language in the book. Look for songs, crafts or games with related vocabulary and structures.

Visit Spanish Playground for more great resources for teaching Spanish to children, and don’t forget that Dia de los niños/ Día de los libros is in just a few weeks! What are you doing to celebrate? What are your favorite books in Spanish to read aloud?

Visit Spanish Playground for more great resources for teaching Spanish to children, and don’t forget that Dia de los niños/ Día de los libros is in just a few weeks! What are you doing to celebrate? What are your favorite books in Spanish to read aloud?

Filed under:

Curriculum Corner,

guest blogger Tagged:

bilingual,

bilingual books,

bilingual education,

Día de los niños/Día de los libros,

ell,

English-Spanish,

Latino/Hispanic/Mexican,

libros en Español,

parents,

Read Aloud,

Reading Aloud,

reading comprehension,

teaching resources

Teaching in U.S. public schools isn't a job or just a career; it's a lifestyle. Those unfamiliar with the work envy teachers their summers off and Xmas holidays. But what comes with the job are 10-12 hrs./day and weekends and holidays spent preparing lesson plans, grading papers and filling out forms. Plus, summer hours preparing for the coming year. For a starting teacher in Denver this works out to be $15/hr. With a master's it goes up to $16.50. Excluded from this is what can easily be $3k out-of-pocket that doesn't get reimbursed. We're not in it for the money; we even pay to be a teacher.

In this Great Recession, having any job is good. I know because I'm presently out of work and seeking a new position with such ridiculously low pay. Like Joe Navarro below, teaching is my passion and calling.

Navarro's letter is a great overall treatment of what's wrong with how the country educates our children. Given the direction of the education discourse nationwide, what he writes about California is significant in that it will likely spread to encompass the remainder of the country. That's his letter's importance.

I won't summarize here my last three years working in one Denver inner city school; maybe I'll write a novel about it one day. I'll just tell you about one student who wasn't one of my bilingual students.

Let's call him Pacifico, because his name is antithetical to his school life and role in it. Pacifico's small for his age, white as a snowflake, unassuming, and worse, sports the thick coke-bottle glasses that should have been outlawed decades ago. I never witnessed any of Pacifico's disruptive behavior, but staff would tell me about various incidents. I've no reason to doubt so many testaments.

I'd often see Pacifico sitting waiting in the office for the principal--in trouble again for hitting, cussing, throwing something, somewhere. I'd talked to him a couple of times in passing, but when I saw him repeatedly eating alone in the cafeteria one week, I went over to him. I assumed he'd been separated from others because of his lunchroom behavior.

"Why are you sitting alone? You being punished?"

"No, I don't like being with the other kids; they pick on me."

"You don't want to sit with your friends?"

"I don't have any."

After that I'd occasionally talk with him, advising him that he at least needed to learn how to stay out of trouble. Sometimes I'd just wish him a good morning--this to a six/seven-year-old who seldom seemed to have few good mornings in his school life. He always acknowledged me, sometimes even breaking out with a crack of a smile, but not often.

My final week of school, having joined the ranks of the not-coming-back-next-year, I tended to avoid staff gatherings and talking with anyone, but on the final day I had to go through the office to hang up my room keys for the last time.

Pacifico was there, possibly not in trouble. He came up close, looked me in the face. "I'm going to miss you." He hugged me like we'd always been the best of buddies, now parting, the message being that he too was leaving.

I don't know that Pacifico hugged everyone that day. Or only me. It doesn't matter. Nor do I know where he's going. Like Navarro below, I don't even know where I'm going.

I do know that should Pacifico grow up to be a sociopathic Columbiner and enter my school, his aim will at least hesitate when it turns on me. On the other hand, he may carry the memory of our moments as something positive that eventually contributes to his not entering a school in such a fashion.

Joe Navarro will tell you now about his torment of retiring as a teacher. I won't, and not because I'm nowhere near retirement. It will be because $15-16 an hour is worth it when it comes with the benefits of Pacifico moments. I

Earlier this week Dan Olivas did a post about a discussion and book signing at UCLA. While we as yet have no posting on the event, I'm in the process of getting a copy of the book to review for La Bloga. In the meantime here's more info below from the publisher, Teachers College Press at Columbia University.

What does this have to do with a Chicano literary site? Demasiado.

What does this have to do with a Chicano literary site? Demasiado.

I live and teach in Denver where only a federal court order prevents the city's Spanish-speaking children from being forced into the Forbidden Language ranks. In recent state elections, English-only referendums have repeatedly raise their ugly heads, though to-date they've luckily been chopped off at the jugular.

Denying all our children the language of Neruda and Marquez is not seen by politicians and others as part of the reason the U.S. trails much of the world in literacy, math, science, etc. Perhaps this book will shed some intelligent light for them to improve their vision.

While I don't know what conclusions the authors reached, they've analyzed practices in three states where English-only proponents unfortunately succeeded in changing state educational policy--California, Arizona and Massachusetts. Should be an interesting read.

Forbidden Language, English Learners and Restrictive Language Policies

Patricia Gandara and Megan Hopkins, Editors

Multicultural Education Series

Pub.: January 2010, 272 pages

Paperback: $32.95, ISBN: 080775045X Cloth: $70.00, ISBN: 0807750468

Pulling together the most up-to-date research on the effects of restrictive language policies, this timely volume focuses on what we know about the actual outcomes for students and teachers in California, Arizona, and Massachusetts—states where these policies have been adopted. Prominent legal experts in bilingual education analyze these policies and specifically consider whether the new data undermine their legal viability. Other prominent contributors examine alternative policies and how these have fared. Finally, Patricia Gándara, Daniel Losen, and Gary Orfield suggest how better policies, that rely on empirical research, might be constructed.

This timely volume:

* Features contributions from well-known educators and scholars in bilingual education.

* Includes an overview of English learners in the United States and a brief history of the policies that have guided their instruction.

* Analyzes the current research on teaching English learners in order to determine the most effective instructional strategies.

“At a time when nativism and ugly anti-immigrant discourse is played out daily on talk radio and cable television, I took hope in reading these chapters, especially when it is clear that learning English is such a priority for these children and their parents. While I doubt that restrictionists will heed its findings, policymakers and educators should read this book carefully.” — Michael A. Olivas, William B. Bates Distinguished Chair in Law, University of Houston

“This volume offers a sobering view of the consequences of making educational policy by referendum, a

Posted on 12/12/2009

Blog:

La Bloga

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

education,

Oregon,

Colorado,

immigrants,

bilingual education,

Rudy Ch. Garcia,

A Grain of Sand,

Mimi's Parranda,

Antique Children,

Lydia Gil,

Add a tag

What's all below doesn't directly reflect the above title, but it came to mind as I composed this.

"They don't want Us here."

The phrase comes up whenever racists, xenophobes, English-onlys and Limbaughers rear their little minds to fill the Internet, town halls or periodicals with opinions inevitably blaming immigrants (legal or otherwise), Spanish-speakers or just plain old U.S.-born, English speaking Chicanos for a laundry list of economic, social or educational failings in this country. On the surface, yes, it sounds, looks and smells like "They don't want Us."

I don't buy the argument, nor the victim-mentality it encourages, because it's a simple reaction to an immediate, specific situation, and no matter how accurate it may be, it fails to include the larger, more complex picture.

They problem lies in the signification They. Without proposing a new conspiracy theory or resurrecting a new one, we tend to throw They around to refer to distinct groups, when we might be better off always thinking of it as the distinct whole--U.S. society, meaning to include the predominant (and some fringe) groups, segments of the population, agencies, governmental bodies, body of law, philosophy and discourse.

When we include all that as They, I'd argue They do want Us here. Someone has to maintain the U.S. hotel toilets, motel bedrooms, Calif. gardens, housing developments and restaurant kitchens at a low enough wage and without drawing down on their tax contributions or good-old-Americans will go without. The food won't get harvested and delivered to those restaurant tables without Us. Manipulating the politics and repressing the economies of Latin America has kept that flow of all types of labor immigrants at an economically profitable level for most of our history.

And after we're here, They still want Us here. The racist, anti-immigrant rhetoric should be interpreted to mean, They want Us here as less-educated scapegoats, the kind that will suffer inhuman abuse in all the verbal, physical and psychological ways that America is so adept at devising. Our norms here are that it's okay to cut off funds to immigrant children, accuse their parents of being members of an ignorant race (sic), while at the same time employing Us at substandard wages without benefits, and even recruiting Us to fight the Iraq-Afghan-Pakistan War.

Homeland Security should erect a monstrous billboard on the border, facing northward, stating:

"Don't leave us. We need your labor and sweat and without you we might realize we're all fokked because we'd have to find new scapegoats and there are enough Muslims around to take all the abuse."

So, the next time your Chicano or mexicano friend says, "They don't want Us here," please try to educate them.

For a good exposure and a set of some real moronic responses, go to "Most Oregon schools slow to get English learners proficient" to see how the Oregon government thinks "punishing" school districts for under serving English language learners can be best implemented by providing even less money for that.

To read about a state notorious for never having understood how to educate Us (Chicano and mexicano kids), and where for years teachers have fought against the myopic standards-based CSAP exam, go to Colorado's new educational standards stress strategic thinking. Dumping the old one doesn't mean a new one will be any better, but th

By Jorge Argueta

Illustrated by Rafael Yockteng

Publisher: Groundwood Books

Pub. Date: April 2009

ISBN-13: 9780888998811

Age Range: 4 to 7

32pp

Synopsis

For people who have left their homeland for a new country, comfort foods from home take on a huge emotional importance. This delightful poem teaches readers young and old how to make a heartwarming, tummy-filling black bean soup, from gathering the beans, onions, and garlic to taking little pebbles out of the beans to letting them simmer till the luscious smell indicates it’s time for supper. Jorge Argueta’s vivid poetic voice and Rafael Yockteng’s vibrant illustrations make preparing this healthy and delicious Latino favorite an exciting, almost magical experience.

LatinoEducators.com

A note from José Luís Orozco

Amigos,

I am writing to give you an exclusive sneak preview of

www.LatinoEducators.com, an on-line community where Spanish-language/bilingual educators and parents can connect and exchange ideas concerning the educational needs of Latino youth. We've been working on the website for a while now and I am excited to announce that we will be publicly launch it before Back to School. Our goal is to create the world's best on-line resource for Latino educators and families.

You can use LatinoEducators.com to:

* Create a profile and meet other people who are passionate about bilingual and dual-language education

* Share videos, photos, lesson plans and experiences

* Keep up to date on conferences and events

* Interact with prominent Spanish-language authors, musicians, academics and thought leaders

Por favor, visit us at

www.LatinoEducators.com and join the conversation around bilingual education!!

El poder de la palabra

Libera a la gente

Aqui la vamos a usar

Aqui decimos PRESENTE.

Jose Luis Orozco

By:

Sondra Santos LaBrie,

on 9/9/2008

Blog:

Happy Healthy Hip Parenting

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

spanish,

libros del mundo,

who's hiding?,

daddy bloggers,

bilingual education,

Quien se esconde?,

employees,

sotoru onishi,

japan,

education,

Add a tag

I couldn't have said it better myself:

Confessions of a Community College Dean shares his understanding of why bilingual education is so important in our culture. If you've ever met anyone from a country outside of the U.S., you might be intimidated, like I am, when you discover how many languages they speak, fluently. There are many cultures who encourage their students to learn not two, but many different languages from an early age. Why should our country be any different?Read on for more from Dean Dad: "In the last few weeks, two of the biggest, most respected and sought after employers in our service area told me, independently and without prompting, that they desperately want bilingual employees.

Given two similarly qualified candidates, one bilingual and the other not, both employers made it abundantly clear to me that they’d hire the bilingual one in a heartbeat. The ability to communicate with Spanish-speaking clients (or, more importantly, potential clients) is a major business advantage, and one for which they’re willing to pay."

Each of the sixteen Kane/Miller Spanish language titles, from our

Libros del Mundo series, are also available in English. These are great resources for young readers, or adults with little knowledge of Spanish, for an introduction to reading, writing, and speaking another language.

What are your thoughts in bilingual education in the U.S.?

![]() Today we are featuring one of First Book’s celebrity blog series. Each month First Book connects with influential voices who share a belief in the power of literacy, and who have worked with First Book to curate a unique collection that inspires a love of reading and learning. All recommended books are available at deeply discounted prices on the First Book Marketplace to educators and programs serving children in need. Peggy McLeod, Ed. D. the Deputy Vice President of Education and Workforce Development at the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), writes on engaging Latino families and children in reading and learning.

Today we are featuring one of First Book’s celebrity blog series. Each month First Book connects with influential voices who share a belief in the power of literacy, and who have worked with First Book to curate a unique collection that inspires a love of reading and learning. All recommended books are available at deeply discounted prices on the First Book Marketplace to educators and programs serving children in need. Peggy McLeod, Ed. D. the Deputy Vice President of Education and Workforce Development at the National Council of La Raza (NCLR), writes on engaging Latino families and children in reading and learning.

I have been reading to my daughter in Spanish since she was a baby (she is now four) but she occasionally rebels. Thanks for these great tips!

Reblogged this on adventureswiththepooh and commented:

If you want to read to your child in Spanish, check out these great tips!