July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, has been blogging regularly for us over the past few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. This is the final installment.

By Gordon Martel

At 6 a.m. in Brussels the Belgian government was informed that German troops would be entering Belgian territory. Later that morning the German minister assured them that Germany remained ready to offer them ‘the hand of a brother’ and to negotiate a modus vivendi. But the basis for any agreement must include the opening of the fortress of Liege to the passage of German troops and a Belgian promise not to destroy railways and bridges.

At the same time the British government was protesting against Germany’s intention to violate Belgian neutrality and requesting from the Belgian government ‘an assurance that the demand made upon Belgium will not be proceeded with, and that her neutrality will be respected by Germany’.

In Berlin they had already anticipated British objections. The German ambassador in London was instructed to ‘dispel any mistrust’ by repeating, positively and formally, that Germany would not, under any pretence, annex Belgian territory. He was to impress upon Sir Edward Grey the reasons for Germany’s decision: they had ‘absolutely unimpeachable’ information that France was planning to attack through Belgium. Germany thus had no choice but to violate Belgian neutrality because it was for them a matter ‘of life or death’.

The assurance was received in London at almost the same moment that the Foreign Office received news that German troops had begun their advance into Belgium.

Two of the four cabinet ministers who had threatened to resign now changed their minds: the news that the Germans had entered Belgium and announced that they would ‘push their way through by force of arms’ had simplified matters.

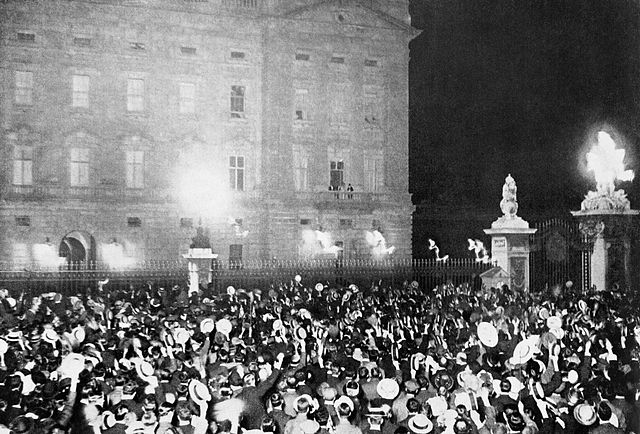

Crowds outside Buckingham Palace after war was declared. Imperial War Museums. IWM Non Commercial Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

At 10.30 a.m. Grey instructed the British minister in Brussels that Britain expected the Belgians to resist any German pressure to induce them to depart from their neutrality ‘by any means in their power’. The British government would support them in their resistance and was prepared to join France and Russia in immediately offering to the Belgian government ‘an alliance’ for the purpose of resisting the use of force by Germany against them, along with a guarantee to maintain Belgian independence and integrity in future years.

At 2 p.m. Grey instructed the ambassador in Berlin to repeat the request he had made last week and again this morning that the German government assure him that it would respect Belgian neutrality. A satisfactory reply was required by midnight, Central European time. If this were not received in time the ambassador was to request his passports and to tell the German government that ‘His Majesty’s Government feel bound to take all steps in their power to uphold the neutrality of Belgium and the observance of a Treaty to which Germany is as much a party as ourselves’.

Before the ambassador could present these demands, the German chancellor addressed the Reichstag, making a long, impassioned speech defending the government’s decision to go to war:

‘A terrible fate is breaking over Europe. For forty-four years, since the time we fought for and won the German Empire and our position in the world, we have lived in peace and protected the peace of Europe. During this time of peace we have become strong and powerful, arousing the envy of others. We have patiently faced the fact that, under the pretence that Germany was warlike, enmity was aroused against us in the East and the West, and chains were fashioned for us.’

A defence of German diplomacy during the crisis followed. Russia alone had failed to agree to ‘localize’ the crisis, to contain it to one that concerned only Austria and Serbia. Germany had warmly supported efforts to mediate the dispute and the Kaiser had engaged the Tsar in a personal correspondence to join him in resolving the differences between Russia and Austria. But Russia had chosen to mobilize all of her forces directed against Austria even though Austria had mobilized only against Serbia. And then Russia had chosen to mobilize all of her forces, leaving Germany with no choice but to mobilize as well.

France had evaded giving a clear answer to the question of whether it would remain neutral in the event of war between Russia and Germany. And then, in spite of promises to keep mobilized French forces 10 kilometres from the frontier with Germany ‘Aviators dropped bombs, and cavalry patrols and French infantry detachments appeared on the territory of the Empire!’

It was true that Germany’s decision to enter Belgium was a violation of international law, but there was no choice: ‘A French attack on our flank on the lower Rhine might have been disastrous’. And Germany would set right the wrong once ‘our military aims have been attained’.

‘We are fighting for the fruits of our works of peace, for the inheritance of a great past and for our future. The fifty years are not yet past during which Count Moltke said we should have to remain armed to defend the inheritance that we won in 1870. Now the great hour of trial has struck for our people. But with clear confidence we go forward to meet it. Our army is in the field, our navy is ready for battle–, and behind them stands the entire German nation– the entire German nation united to the last man.’

At almost the same moment Poincaré was addressing the French Chamber of Deputies. But indirectly, as the constitution prohibited the president from addressing the deputies directly. The minister of justice read his speech for him:

‘France has just been the object of a violent and premeditated attack, which is an insolent defiance of the law of nations. Before any declaration of war had been sent to us, even before the German Ambassador had asked for his passports, our territory has been violated.’….

‘Since the ultimatum of Austria opened a crisis which threatened the whole of Europe, France has persisted in following and in recommending on all sides a policy of prudence, wisdom, and moderation. To her there can be imputed no act, no movement, no word, which has not been peaceful and conciliatory.’….

‘In the war which is beginning, France will have Right on her side, the eternal power of which cannot with impunity be disregarded by nations any more than by individuals. She will be heroically defended by all her sons; nothing will break their sacred union before the enemy; today they are joined together as brothers in a common indignation against the aggressor, and in a common patriotic faith.’

‘Haut les coeurs et vive la France!’

At Buckingham palace at 10.45 the king had convened a meeting of the Privy Council for the purpose of authorizing the declaration of war. They waited for 11 p.m. to come, and when Big Ben struck they were at war. Meanwhile people had begun gathering outside the palace. When news began to spread throughout the crowd that war had been declared the excitement mounted; and when the king, the queen, and their eldest son appeared on the balcony ‘the cheering was terrific.’

By the end of the day five of the six Great Powers of Europe were at war, along with Serbia and Belgium. Diplomacy had failed. The tragedy had begun.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Tuesday, 4 August 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.