By Ronald Schechter

This past 5 July was Daniel Mendoza’s 250th birthday. Or was it? Most biographical sources say that Mendoza was born in 1764. The Encyclopedia Britannica, the Encyclopedia Judaica, Chambers Biographical Dictionary, and the Encyclopedia of World Biography all give 1764 for Mendoza’s year of birth, as do the the websites of the International Boxing Hall of Fame, the International Jewish Hall of Fame, WorldCat, and Wikipedia. The blue plaque on the house in Bethnal Green where Mendoza lived states that he was born in 1764. Indeed, Mendoza’s own memoirs claim that he was born on 5 July 1764.

But the records of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue at Bevis Marks in London indicate that Mendoza was actually born in 1765. Thanks to the work of Lewis Edwards, who reported his findings in a lecture to the Jewish Historical Society of England in 1938, and whose paper was subsequently published in the Transactions of that society, we know that the Mendoza was circumcised on 12 July 1765, 249 years ago today. Jewish law requires infant boys to be circumcised on the eighth day after birth, and this would suggest a birth date of 4 July 1765. (Edwards writes that “we must take the date of birth to have been 5 July 1765,” but in that case Mendoza would only have been seven days old when he was circumcised, which would have violated Jewish law.) It would be quite a coincidence if another Daniel Mendoza had been born on 4 July 1765, and our Daniel Mendoza, whose family belonged to the same synagogue, had been missing from the circumcision records of the previous year. It is equally unlikely that Mendoza would have been circumcised at the age (almost exactly) of one year. Moreover, Edwards consulted the records of the Grand Lodge of Freemasons and found that “Daniel Mendoza, tobacconist, of Bethnal Green, aged 22,” was initiated into the society at some time between 29 October 1787 and 12 February 1788. We know from his memoirs that Mendoza had worked in a tobacconist’s shop between 1782 and 1787, and letters he wrote to the newspapers in 1788 gave his address as “Paradise-Row, Bethnal Green.” So it is reasonable to assume that the new initiate was Daniel Mendoza the pugilist.

Is it possible that Mendoza was mistaken about his own birth date? This seems unlikely, since if he knew he was 22 in late 1787 or early 1788 when he registered with the Freemasons, he should have known he was born in 1765. A printer’s error is more likely the cause. One can easily imagine a printer, or an apprentice, switching the type and accidently entering his “5” after “July” and placing his “4” after “176,” thereby changing 4 July 1765 to 5 July 1764. Whatever the reason for the error, once it was made it was bound to be repeated. When reporting on Mendoza’s death in September 1836, the Morning Post wrote that the boxer “had reached his 73rd year,” as did Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, when in fact he died in his 72nd. And the proliferation of this false information in the years following Mendoza’s death made made it “common knowledge.” Despite Edwards’s careful research, most of the people who have written about Mendoza in the last three quarters of a century have repeated the earlier mistake.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.

So let’s find some fitting way to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mendoza’s birth, but let’s do it next year, and on the 4th of July.

Ronald Schechter is Associate Professor of History at the College of William and Mary. He is the author of Obstinate Hebrews: Representations of Jews in France, 1715-1815 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003) and translator of Nathan the Wise by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing with Related Documents (Boston and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). He is author of the graphic history Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism, illustrated by Liz Clarke. His research interests include Jewish, French, British, and German history with a focus on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

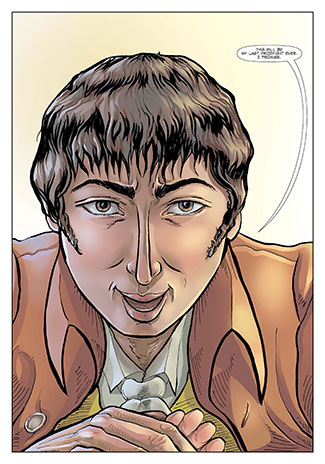

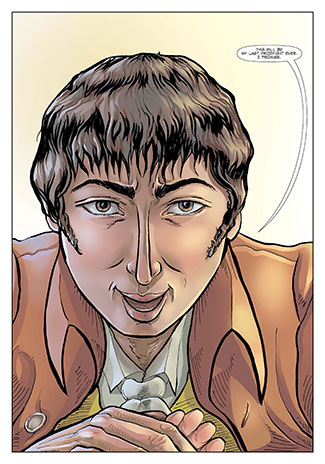

Images from Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism, illustrated by Liz Clarke. Do not use without permission.

The post Daniel Mendoza: born on the 4th of July (249 years ago) appeared first on OUPblog.

By Ronald Schechter

Let me begin with a confession. I used to be a snob when it came to comics. I learned to read circa 1970 and even though my first books were illustrated, there was something about the comic format – the words confined to speech and thought bubbles and the scenes subdivided into frames – that felt less than serious. The only time I remember being allowed to buy comic books was when I had just been to the doctor’s office. Comics were a reward and a comfort for putting up with a cold or the flu or an injection. They were to literature what ice cream was to cuisine. I know I wasn’t alone, and that there are cultural-historical reasons why the adults of my childhood were suspicious of comics. The form itself represented an independent youth culture with its hints of rebelliousness, idleness, sexuality and delinquency, even if I was only reading Richie Rich (an establishment comic if ever there was one) or Caspar the Friendly Ghost.

I would like to say that I came to appreciate the graphic form when I was living in Paris in the early 1990s and when imaginative, beautiful, and thought-provoking bandes-dessinées graced the shelves of serious bookstores on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. That would make me sound sophisticated and open-minded. Unfortunately it wouldn’t be true. I stayed away from that section of the bookstore and concentrated on imageless books, preferably thick in-octavo volumes with pages no larger than six by eight inches.

In the late 90s I was given Art Spiegelman’s Maus as a gift, but I left it on a shelf until my teenage son read it about a decade later and recommended it to me. I then read it and was moved, as many readers have been, but I had misgivings about a book that represented the Holocaust as a kind of fable with animals playing the roles. In retrospect I believe it was the form of the comic book itself that troubled me most. How could the memory of Holocaust victims be honored with something as profane as a comic book? Again, I was still in the thrall of a culture that had an irrational prejudice against illustrated stories divided into (usually) six frames per page and with text contained in speech and thought bubbles. A comic book was profane because, well, it was a comic book.

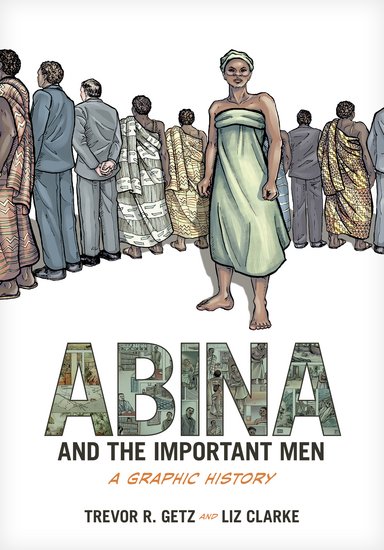

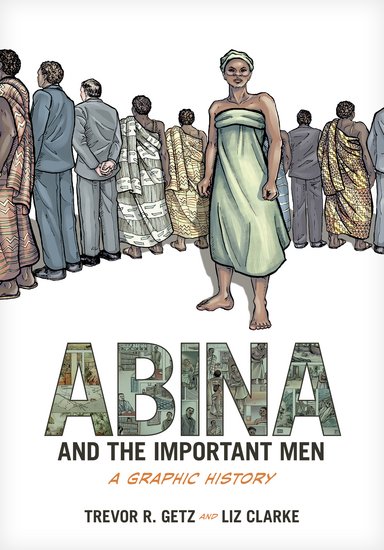

So when a representative at Oxford University Press for Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. gave me a copy of a “graphic history” called Abina and the Important Men, written by Trevor Getz and illustrated by Liz Clarke, I wasn’t necessarily the best candidate for adopting the book. I flipped through it and couldn’t help being gripped by the images of a young woman from the Gold Coast who had taken her employer to court in 1876 for illegally enslaving her, but I placed it on my shelf along with the many other books I had received from publishers. I would think about it, I told myself, but then stopped thinking about it. It wasn’t until I ran into my learned friend Mack Lundy that I thought about the book again. Mack said, “Have you seen a book called Abina and the Important Men? I just picked it up at the College bookstore yesterday and it’s amazing.” Mack is an IT specialist at my College library and is not required to read college history textbooks as part of his job, and he even wrote about the book on his Africa-themed blog. This made his endorsement of the book all the more persuasive.

It happened to be the time of year when I had to choose books to adopt for my courses the following semester, so I read Abina. “My students will love this,” I thought. (Imagine a college professor with this thought written out in a “thought bubble.”) There was something condescending in that thought. I could have chosen a real book to assign, the sort of book I would love, but as a favor to my students I would give them a break and assign a comic book.

As it turned out, Abina was quite challenging, even more challenging than many of the convential-form books I otherwise assign. This was not only because of the complex subject matter, involving such themes as global trade, imperialism, diplomacy, and human rights, but because it thematized the interpretive work historians do when making sense of historical evidence. In other words, it provided a lesson in historical methodology, something few undergraduate course books do. It accomplished this in two ways. First, it included the court transcript of Abina’s case. This gave students the opportunity to compare the primary source with the secondary source (in this case the graphic history). But the second way was inherent to the graphic form itself. The color pictures, the expressions on the faces, the gestures, the dialogue and the thoughts imputed to the characters made it very clear that the history being told was a work of the imagination.

Historians are sometimes reluctant to discuss the role of the imagination in the production of their work, especially when speaking to students who (it might be feared) could mistake imagination for wholesale invention. But students benefit from the knowledge that historians do not simply report what they find in the archives. They give it a form, choose some elements and leave others out, and tell a story. They do this even when they choose an analytical approach to exposition. The narrative aspect of history-writing is graphically clear in the graphic form.

Ronald Schechter is Associate Professor of History at the College of William and Mary. He is the author of Obstinate Hebrews: Representations of Jews in France, 1715-1815 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003) and translator of Nathan the Wise by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing with Related Documents (Boston and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). He is author of the graphic history Mendoza the Jew: Boxing, Manliness, and Nationalism, illustrated by Liz Clarke. His research interests include Jewish, French, British, and German history with a focus on the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Writing a graphic history: Mendoza the Jew appeared first on OUPblog.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.

Why does any of this matter? What difference does it make if Mendoza was 21 and not 22 when he defeated Martin the Butcher? Probably not much. Am I being pedantic by trying to determine the exact date of Mendoza’s birth? Not entirely. If historians are less than rigorous with details that “don’t matter,” we are likely to be lax when they do matter. Moreover, there is a case to be made that Mendoza’s birth year does matter. After all, we are dealing with a commemoration. The bicentennary of the French Revolution was commemorated in 1989, and any attempt to move it up to 1988 would have been seen as misguided. Similarly, Americans would have balked at the suggestion that they celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1975 rather than 1976. The birth of a famous boxer is in a different category of world-historical importance, to be sure, but commemoration is commemoration, and it obeys certain rules. Centuries and half-centuries are more important than decades, which take precedence over individual years. How would you feel if you went to celebrate your grandmother’s 100th birthday only to find out when you arrived at the party that she was 99 (and that her birthday was the previous day)? You would wish her well, but somehow it wouldn’t be the same.