new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2015 Newbery contender, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 14 of 14

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2015 Newbery contender in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

And thus, we end. Though, with such a late ALA Media Awards announcement this year (Monday, February 2nd!) my predictions are coming a bit early in the game. Still, it’s not as though I’ll be seeing much that’s new between now and 2/2. I have watched with great interest the discussions on Heavy Medal and Calling Caldecott. I’ve discussed and debated the contenders with folks of all sorts. I’m eyeing the Mock Caldecotts and Mock Newberys with great fervor as they post their results (and I’m tallying them for my next Pre-Game / Post-Game Show). I’ve gauged the wind. Asked the Magic 8 ball. Basically I’ve done everything in my power to not be to embarrassed when my predictions turn out to be woefully inaccurate. And they will be. Particularly in the Caldecott department. Still, I press on!

I should mention that that throughout the year I mention the books that I think we should all be discussing. This post is a little different. It’s the books I think will actually win. Not the ones I want to win necessarily but the books that I think have the best chance. Here then are my thoughts, and may God have mercy on my soul:

Newbery Award

Winner: Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

What was it I wrote in my Fall Prediction Edition? Ah yes. “This is Woodson’s year and we’re just living in it.” Even without the National Book Award brouhaha and the fact that this book is being purchased by everyone from POTUS on down, Jackie would win in this category. Why the certainty? Well, I’m a big fan of thematic years. I like to take the temperature of the times and work from there. Look back at 2014 and what will we remember? #WeNeedDiverseBooks for one. The Newbery committee canNOT take such things into account, but it’s in the air. They breathe it just like we do and it’s going to affect the decision unconsciously. It doesn’t hurt matters that this is THE book of the year on top of everything else. Magnificently written by an author who has deserved the gold for years, I haven’t been this certain of a book’s chances since The Lion and the Mouse (and, before that, When You Reach Me).

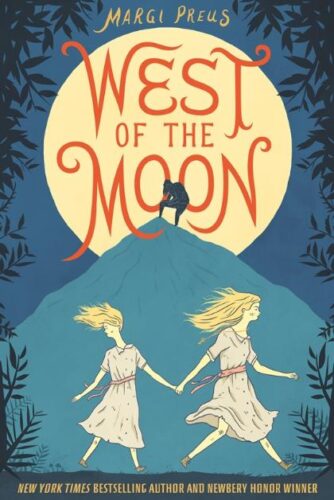

Honors: West of the Moon by Margi Preus

Not a certainty but what is? It’s just enormously difficult not to appreciate what Preus is doing in this book. Mind you, my librarians were not entirely taken with it. Some disliked the heroine too much. Others found it dense. And perhaps it is a “librarian book” intended for gatekeepers more than kids, but I cannot look at the title and not see the word “distinguished” floating above it like a Goodyear Blimp.

Honors: Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson

Also not a sure thing but I think we’d do well to remember it. Wilson’s one of those guys who drifts just under the radar until BLAMMO! Amazing book. Read the first page of this book all by itself. Right there, he’s got you. I can’t help but keep thinking about it. I try to bring up other potential winners, but again and again I turn to this one. Zombie Beowulf. It’s about time.

Honors: The 14th Goldfish by Jennifer L. Holm

Hm. Tricksy. Jenni has this magnificent ability to accrue Honor after Honor after Honor. I’m not seeing gold written all over this book (that’s a lie . . . the gold would complement the blue of the cover so well and fit on the left side of the neck of the beaker, don’t you think?) but it’s a contender. Committees adore her writing, and why not? She’s one of the best. Newbery Honor best? I’m going to say yes.

Wild Card: The Family Romanov by Candace Fleming

YA but not too YA. Certainly pushes the old 0-14 age range, but still a beaut. With Brown Girl Dreaming as well, we might end up with a very strong nonfiction Newbery year (and won’t Common Core be pleased with that?). Mind you, if I hesitate to predict this as an Honor it has more to do with the fact that my heart was broken when Candy didn’t receive any award love for her brilliant Amelia Lost biography. Shouldawonshouldawonshouldawonshouldawon . . .

Wild Card: The Night Gardener by Jonathan Auxier

Doll Bones Honored so why not another creepy little middle grade book? Auxier pulls out all the stops here and is seriously literary in the process. Is it distinguished? Yep. There’s serious heart and guts and other portions of the anatomy at work here. It’s a smart book but appealing too. Never downplay child appeal. It’s worth considering.

Wild Card: The Riverman by Aaron Starmer

It’s probably a good sign when you can’t stop thinking about a book, right? Again, we’re pushing up against the upper limits of the age restriction on Newbery Award winners here, but the book is worth it. Objections I’ve heard lobbed against it say that Alexander doesn’t sound like a kid. Well . . . actually, he’s not supposed to but you don’t really find that out until the second book. So does that trip up the first one’s chances? Maybe, but at least it’s consistent. The objection that Aquavania isn’t realistic enough of a fantasy world would hold more weight if I thought it really WAS a fantasy world, but I don’t. I think it’s all in the characters’ heads. So my weird self-justifications seem to keep this one in the mix. The only questions is, am I the only one?

Wild Card: The Crossover by Kwame Alexander

I’m ashamed to say that I hadn’t even seriously considered this one until a friend of mine brought it up this weekend. And OF COURSE it’s a contender! I mean just look at that language. It sizzles on the page. I’m more than a little peeved that he didn’t garner a NAACP Image Award nomination for this title. If he wins something it’s going to make them look pretty dang silly, that’s for sure. They nominated Dork Diaries 8 and not THIS?!? Okay, rant done. In the end it’s brilliant and, amazingly enough, equally beloved of YA and children’s librarians. The Crossover is a crossover title. Who knew?

By the way, am I the only one with a shelf in my home of 2014 books that have Newbery potential and that I don’t want to read but am holding onto just in case I have to read them? They ain’t gonna Moon Over Manifest me this year, by gum! I am prepared!

Caldecott Award

Winner: Draw by Raul Colon

Betcha you didn’t see that one coming, eh? But honestly, I think this is where we’re heading. First off, this isn’t one of my favorites of the year. I’m just not making the emotional connection with it that I’d like to. My favorite Colon of 2014? Abuelo by Arthur Dorros. But no one’s talking about that one (more fool they). No, they like this one and as I’ve watched I’ve seen it crop up on more and more Best Of lists. Then I sat down and thought about it. Raul Colon. It’s ridiculous that he doesn’t have a Caldecott Gold to his name. He’s one of the masters of the field and this could easily be a case of the committee unconsciously thinking, “Thank God! Now we can give the man an award!” We haven’t had a Latin American gold winner since David Diaz’s Smoky Night (talk about a book tied to its time period). It just makes perfect sense. Folks love it, it’s well done, and it could rise to the top.

Honors: The Farmer and the Clown by Marla Frazee

Again, not one of my favorites. I love Marla Frazee and acknowledge freely that though I don’t get this book, I seem to be the only one who doesn’t (my husband berates me repeatedly for my cold cold heart regarding this title). I mean, I absolutely adore the image of the little clown washing the smile off of his face, revealing his true feelings. So since I’ve apparently a gear stuck in my left aorta, I’m going to assume that this is a book that everyone else sees clearly except me. It could go gold, of course. It seems to have an emotional hold on people and books with emotional holds do very well in the Caldecott race sometimes. We shall see.

Honors: Bad Bye, Good Bye by Deborah Underwood, ill. Jonathan Bean

Could be wishful thinking on my part, but look at the book jacket, man. Look at how it tells the entire story. Look at his technique. Isn’t it marvelous? Look at how it’s not just an emotional journey but a kind of road trip through Americana as well. Look at how he took this spare sparse text and gave it depth and feeling and meaning. That is SERIOUSLY hard to do with another author’s work!! Look at how beautiful it is and the emotionally satisfying (and accurate) beats. Look upon its works, ye mighty, and despair. Or give it a Caldecott Honor. I’m easy.

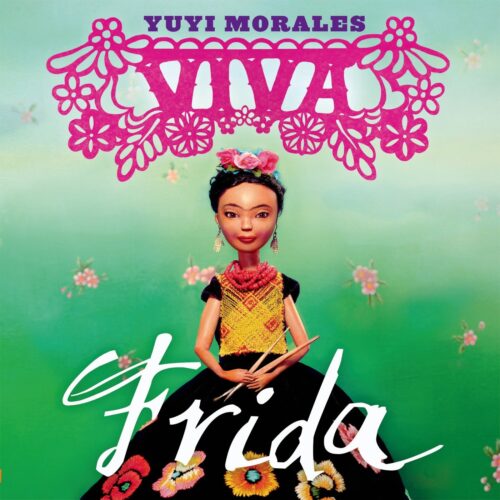

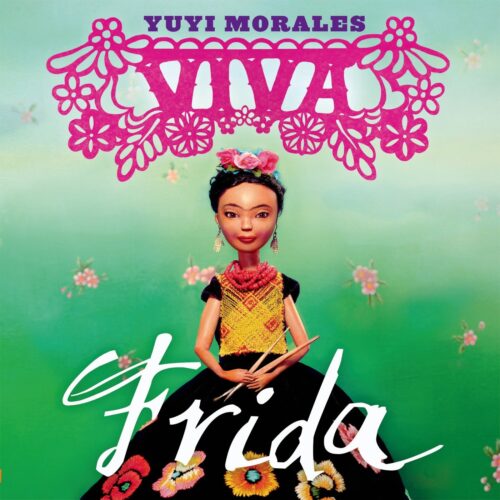

Honors: Viva, Frida by Yuyi Morales

Admittedly it’s not a shoo-in. In fact I’m a bit baffled that it didn’t show up on the recent list by Latinas for Latino Lit called Remarkable Latino Children’s Literature of 2014. There are admittedly some folks who want this to be a biography and have a hard time dealing with the fact that that is not its raison d’etre. Still others aren’t blown away by the text. That said, we’re not looking at the text. We’re looking at the imagery and the imagery is STUNNING. I mean, it could win the gold easily, don’t you think? Models and photography and two-dimensional art? Yuyi Morales should have won a Caldecott years ago. I think it’s finally time to give the woman some love.

Wild Card: Three Bears in a Boat by David Soman

“I still . . . I still, beeelieeeve!!!!” Okay. So maybe it’s just me. But when I sit down and I look and look and look at that image of the three little bears sailing into the sun with the light reflected off the water . . . *sigh* It’s amazing. I heard a very odd objection from someone saying that the bears don’t always look the same age from spread to spread. Bull. Do so. Therein ends my very coherent defense. It’s my favorite and maybe (probably) just mine, but I love it so much that I can’t give it up. I just can’t.

Wild Card: Neighborhood Sharks by Katherine Roy

Because how cool would it frickin’ be? Few have looked at this book and considered it for a Caldecott, but that’s just because they’re not looking at it correctly. Consider the cinematic imagery. The downright Hitchcockian view of the seal up above where YOU are the shark below. The two page attack! The beauty of blood in the water. I mean, it’s gorgeous and accurate all at once. I don’t think anyone’s giving the woman enough credit. Give it a second glance, won’t you?

And that’s it! There are loads and loads of titles missing from this list. The actual winners, perhaps. But I’m feeling confident that I’ve nailed at least a couple of these. We shall see how it all falls out soon enough. See you in February!!

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/3/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

verse novels,

middle grade historical fiction,

middle grade verse novels,

Skila Brown,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Add a tag

Caminar

Caminar

By Skila Brown

Candlewick Press

$15.99

ISBN: 978-0763665166

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Survivor’s guilt. Not the most common theme in children’s books these days. Not unheard of certainly, but it definitely doesn’t crop up as often as, say, stories about cupcakes or plucky orphans that have to defeat evil wizards. Serious works of fiction do well when award season comes along, but that’s only because those few that garner recognition are incredibly difficult to write. I’ll confess to you that when I first encountered Caminar by Skila Brown I heard it was about a kid surviving Guatemala’s Civil War and I instantly assumed it would be boring. Seems pretty silly to say that I thought a book chock-full o’ genocide would be a snorefest, but I’ve been burned before. True, I knew that Caminar was a verse novel and that gave me hope, but would it be enough? Fortunately, when the time came to pick it up it sucked me in from the very first page. Gripping and good, horrifying and beautifully wrought, if you’re gonna read just one children’s book on a real world reign of terror, why not go with this one?

He isn’t big. He isn’t tall. He has the round face of an owl and he tends to do whatever it is his mother requires of him with very little objection. Really, is it any wonder that Carlos is entranced by the freedom of the soldiers that enter his small village? The year is 1981 and in Chopan, Guatemala things are tense. One minute you have strange soldiers coming through the village on the hunt for rebels. The next minute the rebels are coming through as well, looking for food and aid. And when Carlos’s mother tells him that in the event of an emergency he is to run away and not wait for her, it’s not what he wants to hear. Needless to say, there comes a day when running is the only option but Carlos finds it difficult to carry on. He can survive in the wild, sleeping in trees and eating roots and plants, but how does he deal with the notion that only cowardice kept him from returning to Chopan? How does he handle his guilt? And is there some act that he can do to find peace of mind once more?

This isn’t the first book containing mass killings I’ve ever encountered for kids. Heck, it’s not even the only one I’ve seen this year (hat tip to The Red Pencil by Andrea Davis Pinkney). As such, this brings up a big question that the authors of such books must wrestle with each and every time such a book is conceived. Mainly, how do you make horrific violence palatable to young readers? A good follow-up question would have to be, why should you make it palatable in the first place? What is the value in teaching about the worst that humanity is capable of? There are folks that would mention that there is great value in this. Some books teach kids that the world is capable of being capricious and cruel with no particular reason whatsoever. Indeed Brown touches on this when Carlos prays to God asking for the answers that even adults seek. When handled well, books about mass killings of any kind, be it the Holocaust or the horrors of Burma, can instruct as well as offer hope. When handled poorly they become salacious, or moments that just use these horrors as an inappropriately tense backdrop to the action.

Here’s what you see when you read the first page of this book. The title is “Where I’m From”. It reads, “Our mountain stood tall, / like the finger that points. / Our corn plants grew in fields, / thick and wide as a thumb. / Our village sat in the folded-between, / in that spot where you pinch something sacred, / to keep it still. / Our mountain stood guard at our backs. / We slept at night in its bed.” I read this and I started rereading and rereading the sentence about how one will “pinch something sacred”. I couldn’t get it out of my head and though I wasn’t able to make perfect sense out of it, it rang true. I’m pleased that it was still in my head around page 119 because at that time I read something significant. Carlos is playing marbles with another kid and we read, “I watched Paco pinch / his fingers around the shooter, pinch / his eyes up every time . . .” Suddenly the start of the book makes a kind of sense that it didn’t before. That’s the joy of Brown’s writing here. She’s constantly including little verbal callbacks that reward the sharp-eyed readers while still remaining great poetry.

If I’m going to be perfectly honest with you, the destruction of Carlos’s village reminded me of nothing so much as the genocide that takes place in Frances Hardinge’s The Lost Conspiracy. That’s a good thing, by the way. It puts you in the scene without getting too graphic. The little bits and pieces you hear are enough. Is there anything more unnerving than someone laughing in the midst of atrocities? In terms of the content, I watched what Brown was doing here with great interest. To write this book she had to walk a tricky path. Reveal too much horror and the book is inappropriate for its intended age bracket. Reveal too little and you’re accused of sugarcoating history. In her particular case the horrors are pinpointed on a single thing all children can relate to: the fear of losing your mother. The repeated beat in this book is Carlos’s mother telling him that he will find her. Note that she never says that she will find him, which would normally be the natural way to put this. Indeed, as it stands the statement wraps up rather beautifully at the end, everything coming full circle.

Brown’s other method of handling this topic was to make the book free verse. Now I haven’t heard too many objections to the book but when I have it involves the particular use of the free verse found here. For example, one adult reader of my acquaintance pretty much dislikes any and all free verse that consists simply of the arbitrary chopping up of sentences. As such, she was incensed by page 28 which is entitled “What Mama Said” and reads simply, “They will / be back.” Now one could argue that by highlighting just that little sentence Brown is foreshadowing the heck out of this book. Personally, I found moments like this to be pitch perfect. I dislike free verse novels that read like arbitrary chopped up sentences too, but that isn’t Caminar. In this book Brown makes an effort to render each poem just that. A poem. Some poems are stronger than others, but they all hang together beautifully.

Debates rage as to how much reality kids should be taught. How young is young enough to know about the Holocaust? What about other famous atrocities? Should you give your child the essentials before they learn possibly misleading information from the wider world? What is a teacher’s responsibility? What is a parent’s? I cannot tell you that there won’t be objections to this book by concerned parental units. Many feel that there are certain dark themes out there that are entirely inappropriate as subject matter in children’s books. But then there are the kids that seek these books out. And honestly, the reason Caminar is a book to seek out isn’t even the subject matter itself per se but rather the great overarching themes that tie the whole thing together. Responsibility. Maturity. Losing your mother. Survival (but at what cost?). A beautifully wrought, delicately written novel that makes the unthinkable palatable to the young.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/15/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

Newbery Award,

Caldecott Award,

Newbery/Caldecott predictions,

Caldecott Honors,

Newbery Honors,

Best Books of 2014,

2015 Newbery contender,

2015 Caldecott contender,

Add a tag

Now we’re in the thick of it. Do you hear that? That is the clicking ticking sound of the reanimation of the Heavy Medal and Calling Caldecott blogs. They’re a little groggy right now, trying to get their bearings, figuring out which foot to try first. But don’t be fooled by their initial speed. Very soon they’ll be acting like well-oiled machines, debating and comparing and contrasting like it’s nobody’s business. But why let them have all the fun? Time for a little predicting on my end as well! I’ve been discussing these books with folks all year and through our debates I’m getting a better sense of the titles that are more likely than others to make it in the end. So, with the inclusion of some fall books, here’s the latest roster of predictions. Please note that as the year goes on I tend to drop books off my list more than I add them. This is also my penultimate list. The final will appear in December.

2015 Newbery Predictions

The Night Gardener by Jonathan Auxier

It’s so satisfying when you like a book and then find that everyone else likes it too. This was the very first book I mentioned in this year’s Spring Prediction Edition of Newbery/Caldecott 2015 and nothing has shaken my firm belief that it is extraordinary. It balances out kid-friendly plotting with literary acumen. It asks big questions while remaining down-to-earth. And yes, it’s dark. 2014 is a dark year. It’ll be compared to Doll Bones, which is not the worst thing in the world. I could see this one making it to the finish line. I really could.

Absolutely Almost by Lisa Graff

You know what? I’m sticking by this one. Graff’s novel has the ability to create hardcore reader fans, even though it has a very seemingly simple premise. It’s librarian-bait to a certain extent (promoting a kid who likes to read Captain Underpants will do that) but I don’t think it’s really pandering or anything. It’s also not a natural choice for the Newbery, preferring subtlety over literary largess. I’m keeping it in mind for now.

West of the Moon by Margi Preus

Notable if, for no other reason, the fact that Nina Lindsay and I agree on it and we rarely agree on anything. As it happens, this is a book I’ve been noticing a big backlash against. It sports a complex and unlikeable heroine, which can prove difficult when assessing its merits. She makes hard, often bad, choices. But personally I feel that even if you dislike who she becomes, you still root for her to win. Isn’t that worth something? Other folks find the blending of historical fiction and fantasy unnerving. I find it literary. You be the judge.

Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson

I could write out yet another defense of this remarkable novel, but I think I’ll let N.D. Wilson do the talking for me instead:

brown girl dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

The frontrunner. This is Woodson’s year and we’re just living in it. I’m waiting to hear the concentrated objections to this book. Waiting because I’m having a hard time fathoming what they might be. One librarian I spoke too complained it was too long. Can’t agree myself, but I noted her comment. Other than that, nobody disagrees that it’s distinguished. As distinguished as distinguished can be, really. If it doesn’t get the gold (look at all the nice sky-space where you could fit in a medal!) I will go on a small rampage.

Dory Fantasmagory by Abby Hanlon

Betcha didn’t see that one coming. You were probably expecting a discussion of Revolution or A Snicker of Magic or something, right? Well darling, I’ll confess something to you. I like simple books. Reeeeally simple books. Books so simple that they cross an invisible line and become remarkably complex. I like books that give you something to talk about for long periods of time. That’s where Hanlon’s easy chapter book comes in. What do I find distinguished about this story? I find the emotional resonance and sheer honesty of the enterprise entirely surprising and extraordinary. And speaking of out-there nominations . . .

Once Upon an Alphabet: Short Stories for All the Letters by Oliver Jeffers

Face facts. Jeffers is a risky Caldecott bid, even when he’s at his best. The man does do original things (This Moose Belongs to Me was probably his best bet since moving to America, though I’d argue that Stuck was the best overall) but his real strength actually lies in his writing. The man’s brain is twisted in all the right places, so when you see a book as beautifully written as this one you have to forgive yourself for wanting to slap medals all over it, left and right. A picture book winning a Newbery is not unheard of in this day and age, but it requires a committee that thinks in the same way. I don’t know this year’s committee particularly well. I can’t say what they will or will not think. All I do know is that this book deserves recognition.

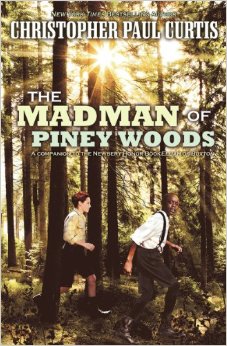

Let the record show that the ONLY reason I am not including The Key That Swallowed Joey Pigza by Jack Gantos in this list is because it does require a bit of familiarity with the other books in the series. I struggle with that knowledge since it’s long been a dream of mine to see a Joey Pigza book with the Newbery gold and this is our last possible chance to do just that. Likewise, I’m not including The Madman of Piney Woods by Christopher Paul Curtis only because knowledge of Elijah of Buxton makes for a stronger ending to the tale But both books are true contenders in every other way.

And now for the more difficult discussions (because clearly Newbery is a piece of cake….. hahahahahahahaha!!! <—- maniacal laughter)

2015 Caldecott Predictions

Bad Bye, Good Bye by Deborah Underwood, ill. Jonathan Bean

I only recently discovered that if you take the jacket off of this book and look at it from left to right you get to see the entire story play out, end to end. What other illustrator goes for true emotion on the bloody blooming jacket of their books? Bean is LONG overdue for Caldecott love. He’s gotten Boston Globe-Horn Book love and Ezra Jack Keats Award love but at this moment in time it’s downright bizarre that he hasn’t a Caldecott or two to his name. Hoping this book will change all that.

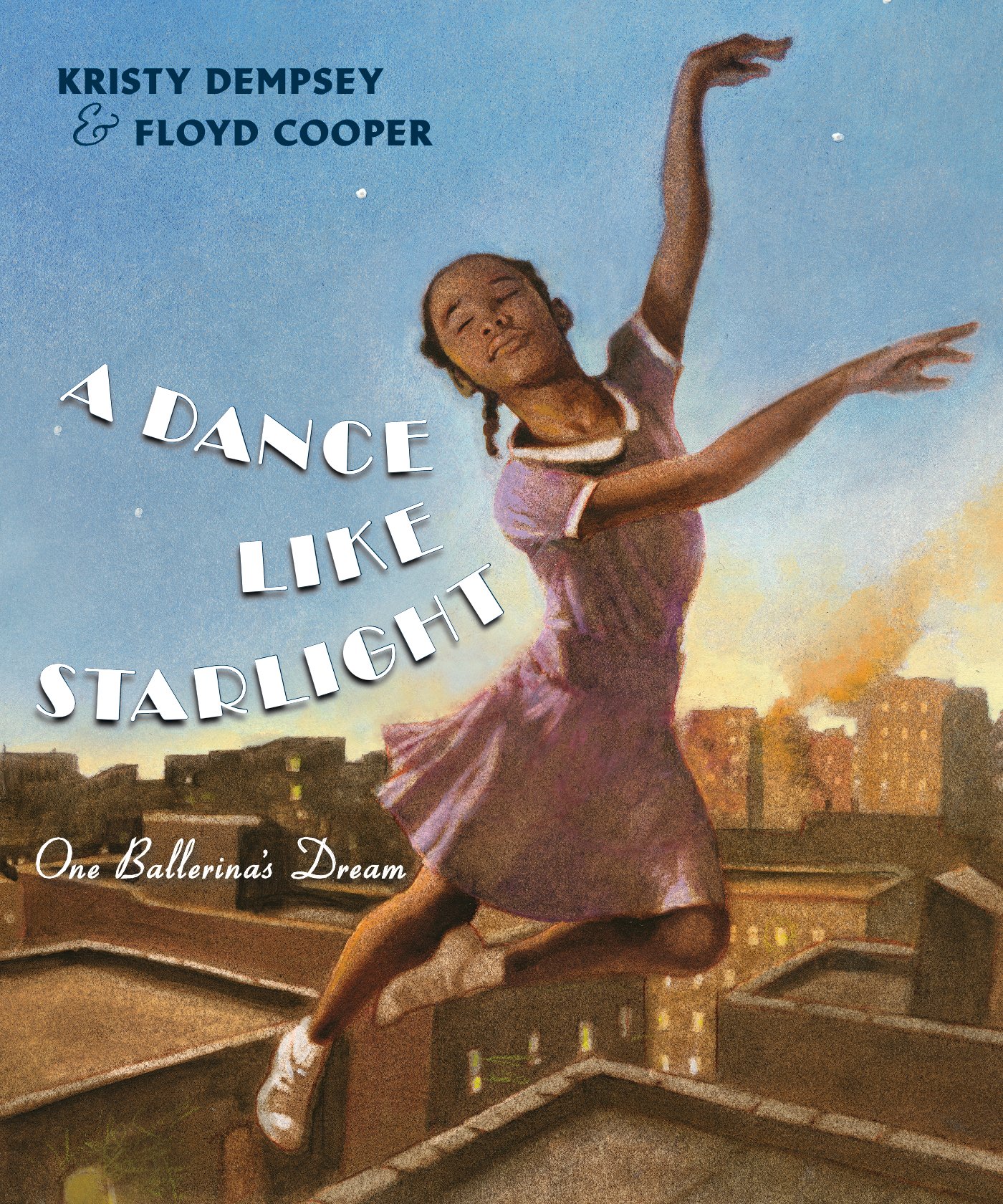

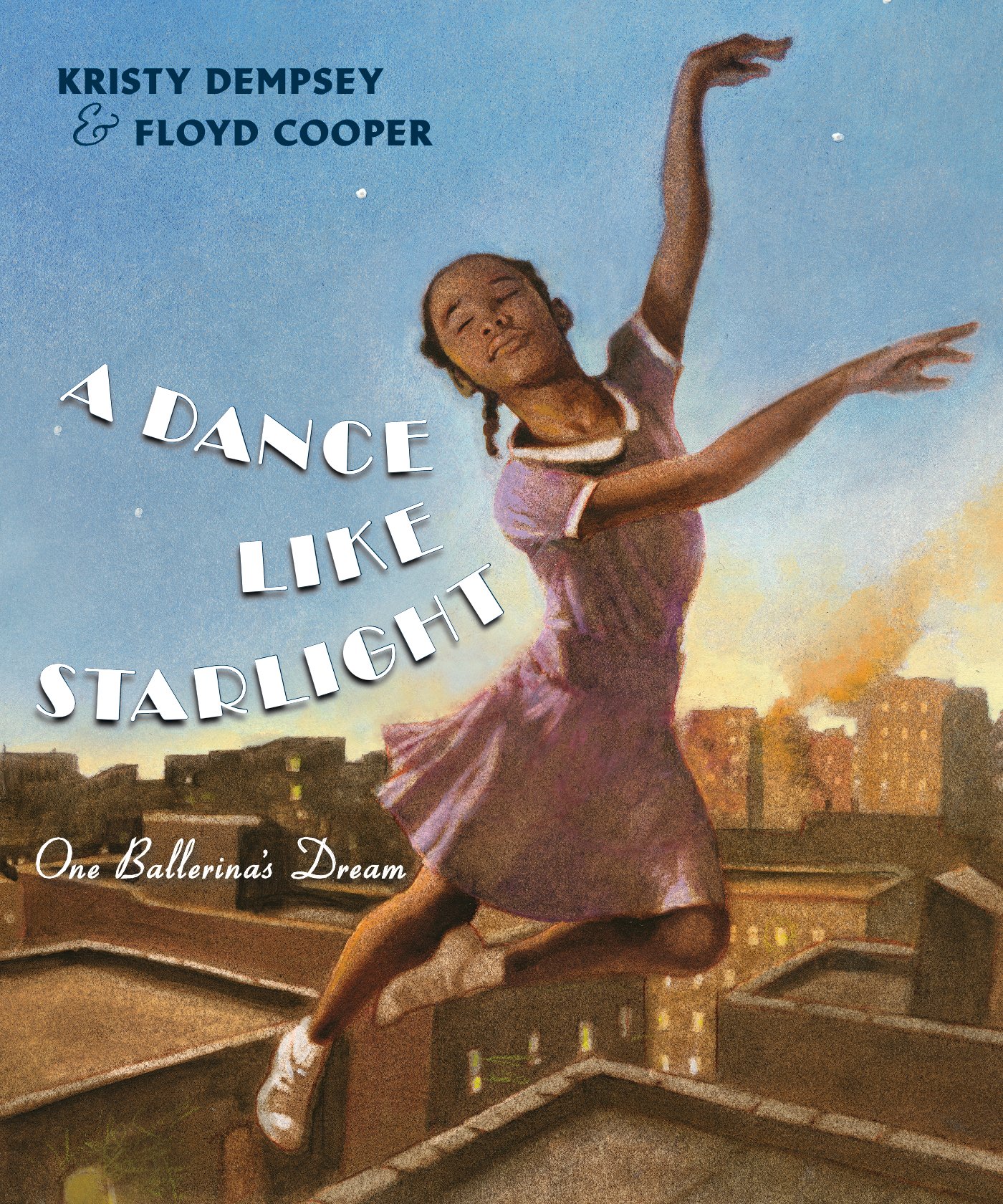

A Dance Like Starlight by Kristy Dempsey, ill. Floyd Cooper

I’m sticking with Floyd here. The man’s paid his dues. This book does some truly lovely things. It’s going to have to deal with potentially running into people who just don’t care for his style. It’s a distinctive one and not found anywhere else, but I know a certain stripe of gatekeeper doesn’t care for it. It’s also one of three African-American ballerina books this year (Ballerina Dreams: From Orphan to Dancer by Michaela and Elaine DePrince, ill. Frank Morrison and Firebird by Misty Copeland, ill. Christopher Myers anyone?) but is undeniably the strongest.

Viva Frida by Yuyi Morales, photographs by Tim O’Meara

People don’t like it when a book doesn’t fall into their preexisting prescribed notions of what a book should do. Folks look at the cover and title of this book and think “picture book biography”. When they don’t get that, they get mad. I’ve heard complaints about the sparse text and lack of nonfiction elements. Yet for all that, nobody can say a single word against the art. “Stunning” only begins to encompass it. I think that if you can detach your mind from thinking of the book as a story, you do far better with it. Distinguished art? You better believe it, baby.

Three Bears in a Boat by David Soman

Seriously, look me in the eye and explain to me how this isn’t everybody’s #1 Caldecott choice. Right here. In the eye.

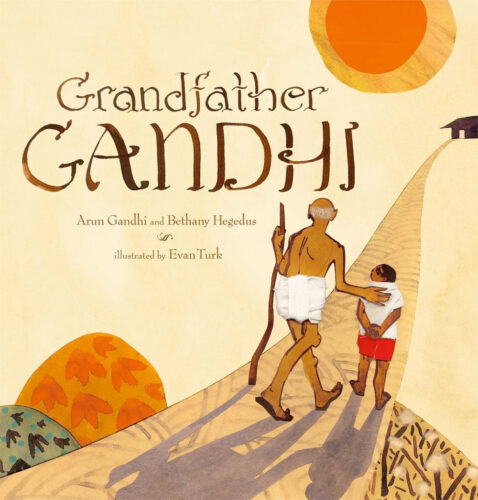

Grandfather Gandhi by Arun Gandhi and Bethany Hegedus, illustrated by Evan Turk

What can I say that I haven’t said a hundred times before? I’ve heard vague whines from folks who don’t care for this art style. *sigh* It happens. I’ll just turn everything over to the author for her perspective on the story behind the story then.

Remy and Lulu by Kevin Hawkes and Hannah E. Harrison

Okay, try to think of a precedent for this one. Let’s say this book won the Caldecott gold. That would mark the very first time in the HISTORY of the award itself that two unmarried artists got a medal for their work, yes? And yet the book couldn’t exist without the two of them working in tandem. Remy and Lulu is an excellent example of a book that I dismissed on an initial reading, yet found myself returning to again and again and again later. And admit it. The similarities in some ways to Officer Buckle and Gloria can only help it, right?

I don’t think I gave this book adequate attention the first time I read it through.

Have You Heard the Nesting Bird? by Rita Gray, ill. Kenard Pak

I heard an artist once criticize the current trend where picture book illustrators follow so closely in the footsteps of Jon Klassen. And you could be forgiven for thinking that animator Kenard Pak is yet another one of these. Yet when you look at this book, this remarkable little piece of nonfiction, you see how the textured watercolors are more than simply Klassen-esque. Pak’s art is delightful and original and downright keen. Can you say as much for many other books?

This is one of those years where the books I’m looking at have NOTHING to do with the books that other folks are looking at. For example, when I look at the list of books being considered at Calling Caldecott, I am puzzled. Seems to me it would make more sense to mention Blue on Blue by Dianne White, illustrated by Beth Krommes, Go to Sleep, Little Farm by Mary Lyn Ray, illustrated by Christopher Silas Neal, or Dragon’s Extraordinary Egg by Debi Gliori (wait . . . she’s Scottish and therefore ineligible?! Doggone the doggity gones . . .).

For additional thoughts, be sure to check out the Goodreads lists of Newbery 2015 and Caldecott 2015 to see what the masses prefer this year.

So! What did I miss?

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/1/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Penguin,

Best Books,

Dial Books for Young Readers,

early chapter books,

Abby Hanlon,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 early chapter books,

Add a tag

Dory Fantasmagory

Dory Fantasmagory

By Abby Hanlon

Dial (an imprint of Penguin)

$14.99

ISBN: 978-0-8037-4088-4

Ages 6-8

On shelves October 9th

Which of the following types of children’s books are, in your opinion, the most difficult to write: Board books, picture books, easy books (for emerging readers), early chapter books, or middle grade fiction (older chapter books)? The question is, by its very definition, unfair. They are all incredibly hard to do well. Now me, I have always felt that easy books must be the hardest to write. You have to take into account not just the controlled vocabulary but also the fact that the story is likely not going to exactly be War and Peace (The Cat in the Hat is considered exceptional for a reason, people). And right on the heels of easy books and their level of difficulty is the early chapter book. You have a bit more freedom with that format, but not by much. For a really good one there should be plenty of fun art alongside a story that strikes the reader as one-of-a-kind. It has to talk about something near and dear to the heart of the kid turning the pages, and if you manage to work in a bit of a metaphor along the way? Then you, my dear, have done the near impossible. The last book I saw work this well was the extraordinary Sadie and Ratz by Sonya Hartnett, a book that to this day I consider a successor to Where the Wild Things Are. I didn’t expect to see another book tread the same path for a while. After all, these kinds of stories are enormously difficult to write (or did I mention that already?). Enter Dory Fantasmagory. Oh. My. Goodness. Pick up my jaw from the floor and lob it my way because this book is AMAZING! Perfection of tone, plot, pacing, art, you name it. Author Abby Hanlon has taken a universal childhood desire (the wish of the younger sibling for the older ones to play with them) and turned it into a magnificent epic fantasy complete with sharp-toothed robbers, bearded fairy godmothers, and what may be the most realistic 6-year-old you’ll ever meet on a page. In a word, fantastico.

She’s six-years-old and the youngest of three. Born Dory, nicknamed Rascal, our heroine enjoys a rich fantasy life that involves seeing monsters everywhere and playing with her best imaginary friend Mary. She has to, you see, because her older siblings Luke and Violet refuse to play with her. One day, incensed by her incessant youth, Violet tells Rascal that if she keeps acting like a baby (her words) she’ll be snatched up by the sharp-toothed robber Mrs. Gobble Gracker (a cousin of Viola Swamp if the pictures are anything to go by). Rather than the intended effect of maturing their youngest sibling, this information causes Rascal to go on the warpath to defeat this new enemy. In the course of her playacting she pretends to be a dog (to escape Mrs. Gobble Gracker’s attention, naturally) and guess what? Luke, her older brother, has always wanted a dog! Suddenly he’s playing with her and Rascal is so ebullient with the attention that she refuses to change back. Now her mom’s upset, her siblings are as distant as ever, Mrs. Gobble Gracker may or may not be real, and things look bad for our hero. Fortunately, one uniquely disgusting act is all it will take to save the day and make things right again.

This is what I like about the world of children’s books: You never know what amazingly talented book is going to come from an author next. Take Abby Hanlon. A former teacher, Ms. Hanlon wrote the totally respectable picture book Ralph Tells a Story. It published with Amazon and got nice reviews. I read it and liked it but I don’t think anyone having seen it would have predicted its follow up to be Dory here. It’s not just the art that swept me away, though it is delightful. The tiny bio that comes with this book says that its creator “taught herself to draw” after she was inspired by her students’ storytelling. Man oh geez, I wish I could teach myself to draw and end up with something half as good as what Hanlon has here. But while I liked the art, the book resonates as beautifully as it does because it hits on these weird little kid truths that adults forget as they grow older. For example, how does Rascal prove herself to her siblings in the end? By being the only one willing to stick her hand in a toilet for a bouncy ball. THAT feels realistic. And I love Rascal’s incessant ridiculous questions. “What is the opposite of a sandwich?” Lewis Carroll and Gollum ain’t got nuthin’ on this girl riddle-wise.

This is what I like about the world of children’s books: You never know what amazingly talented book is going to come from an author next. Take Abby Hanlon. A former teacher, Ms. Hanlon wrote the totally respectable picture book Ralph Tells a Story. It published with Amazon and got nice reviews. I read it and liked it but I don’t think anyone having seen it would have predicted its follow up to be Dory here. It’s not just the art that swept me away, though it is delightful. The tiny bio that comes with this book says that its creator “taught herself to draw” after she was inspired by her students’ storytelling. Man oh geez, I wish I could teach myself to draw and end up with something half as good as what Hanlon has here. But while I liked the art, the book resonates as beautifully as it does because it hits on these weird little kid truths that adults forget as they grow older. For example, how does Rascal prove herself to her siblings in the end? By being the only one willing to stick her hand in a toilet for a bouncy ball. THAT feels realistic. And I love Rascal’s incessant ridiculous questions. “What is the opposite of a sandwich?” Lewis Carroll and Gollum ain’t got nuthin’ on this girl riddle-wise.

For me, another part of what Dory Fantasmagory does so well is get the emotional beats of this story dead to rights. First off, the premise itself. Rascal’s desperation to play with her older siblings is incredibly realistic. It’s the kind of need that could easily compel a child to act like a dog for whole days at a time if only it meant garnering the attention of her brother. When Rascal’s mother insists that she act like a girl, Rascal’s loyalties are divided. On the one hand, she’ll get in trouble with her mom if she doesn’t act like a kid. On the other hand, she has FINALLY gotten her brother’s attention!! What’s more, Rascal’s the kind of kid who’ll get so wrapped up in imaginings that she’ll misbehave without intending to, really. Parents reading this book will identify so closely to Rascal’s parents that they’ll be surprised how much they still manage to like the kid when all is said and done (there are no truer lines in the world than when her mom says to her dad, “It’s been a looooooooong day”). But even as they roll their eyes and groan and sigh at their youngest’s antics, please note that Rascal’s mom and dad do leave at least two empty chairs at the table for her imaginary companions. That ain’t small potatoes.

It would have been simple for Hanlon to go the usual route with this book and make everything real to Abby without a single moment where she doubts her own imaginings. Lots of children’s books make use of that imaginative blurring between fact and fiction. What really caught by eye about Dory Fantasmagory, however, was the moment when Rascal realizes that in the midst of her storytelling she has lost her sister’s doll. She thinks, “Oh! Where did I put Cherry? I gave her to Mrs. Gobble Gracker, of course. But what did I REALLY ACTUALLY do with her?” This is the moment when the cracks in Rascal’s storytelling become apparent. She has to face facts and just for once see the world for what it is. And why? Because her older sister is upset. Rascal, you now see, would do absolutely anything for her siblings. She’d even destroy her own fantasy world if it meant making them happy.

It would have been simple for Hanlon to go the usual route with this book and make everything real to Abby without a single moment where she doubts her own imaginings. Lots of children’s books make use of that imaginative blurring between fact and fiction. What really caught by eye about Dory Fantasmagory, however, was the moment when Rascal realizes that in the midst of her storytelling she has lost her sister’s doll. She thinks, “Oh! Where did I put Cherry? I gave her to Mrs. Gobble Gracker, of course. But what did I REALLY ACTUALLY do with her?” This is the moment when the cracks in Rascal’s storytelling become apparent. She has to face facts and just for once see the world for what it is. And why? Because her older sister is upset. Rascal, you now see, would do absolutely anything for her siblings. She’d even destroy her own fantasy world if it meant making them happy.

Beyond the silliness and the jokes (of which there are plenty), Hanlon’s real talent here is how she can balance ridiculousness alongside honest-to-goodness heartwarming moments. If you look at the final picture in this book and don’t feel a wave of happy contentment then you, sir, have no soul. The book is a pure pleasure and bound to be just as amusing to kids as it is to adults. Like older works for children like Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key, Dory Fantasmagory manages to make a personality type that many kids would find annoying in real life (in this case, a younger sibling) into someone not only understandable but likeable and sympathetic. If it encourages only one big brother or sister to play with their younger sibs then it will have justified its existence in the universe. And I think it shall, folks. I think it shall. A true blue winner.

On shelves October 9th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Scholastic,

Best Books,

Christopher Paul Curtis,

middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

The Madman of Piney Woods

The Madman of Piney Woods

By Christopher Paul Curtis

Scholastic

ISBN: 978-0-545-63376-5

$16.99

Ages 9-12

On shelves September 30th

No author hits it out of the park every time. No matter how talented or clever a writer might be, if their heart isn’t in a project it shows. In the case of Christopher Paul Curtis, when he loves what he’s writing the sheets of paper on which he types practically set on fire. When he doesn’t? It’s like reading mold. There’s life there, but no energy. Now in the case of his Newbery Honor book Elijah of Buxton, Curtis was doing gangbuster work. His blend of history and humor is unparalleled and you need only look to Elijah to see Curtis at his best. With that in mind I approached the companion novel to Elijah titled The Madman of Piney Woods with some trepidation. A good companion book will add to the magic of the original. A poor one, detract. I needn’t have worried. While I wouldn’t quite put Madman on the same level as Elijah, what Curtis does here, with his theme of fear and what it can do to a human soul, is as profound and thought provoking as anything he’s written in the past. There is ample fodder here for young brains. The fact that it’s a hoot to read as well is just the icing on the cake.

Two boys. Two lives. It’s 1901, forty years after the events in Elijah of Buxton and Benji Alston has only one dream: To be the world’s greatest reporter. He even gets an apprenticeship on a real paper, though he finds there’s more to writing stories than he initially thought. Meanwhile Alvin Stockard, nicknamed Red, is determined to be a scientist. That is, when he’s not dodging the blows of his bitter Irish granny, Mother O’Toole. When the two boys meet they have a lot in common, in spite of the fact that Benji’s black and Red’s Irish. They’ve also had separate encounters with the legendary Madman of Piney Woods. Is the man an ex-slave or a convict or part lion? The truth is more complicated than that, and when the Madman is in trouble these two boys come to his aid and learn what it truly means to face fear.

Let’s be plainspoken about what this book really is. Curtis has mastered the art of the Tom Sawyerish novel. Sometimes it feels like books containing mischievous boys have fallen out of favor. Thank goodness for Christopher Paul Curtis then. What we have here is a good old-fashioned 1901 buddy comedy. Two boys getting into and out of scrapes. Wreaking havoc. Revenging themselves on their enemies / siblings (or at least Benji does). It’s downright Mark Twainish (if that’s a term). Much of the charm comes from the fact that Curtis knows from funny. Benji’s a wry-hearted bigheaded, egotistical, lovable imp. He can be canny and completely wrong-headed within the space of just a few sentences. Red, in contrast, is book smart with a more regulation-sized ego but as gullible as they come. Put Red and Benji together and it’s little wonder they’re friends. They compliment one another’s faults. With Elijah of Buxton I felt no need to know more about Elijah and Cooter’s adventures. With Madman I wouldn’t mind following Benji and Red’s exploits for a little bit longer.

One of the characteristics of Curtis’s writing that sets him apart from the historical fiction pack is his humor. Making the past funny is a trick. Pranks help. An egotistical character getting their comeuppance helps too. In fact, at one point Curtis perfectly defines the miracle of funny writing. Benji is pondering words and wordplay and the magic of certain letter combinations. Says he, “How is it possible that one person can use only words to make another person laugh?” How indeed. The remarkable thing isn’t that Curtis is funny, though. Rather, it’s the fact that he knows how to balance tone so well. The book will garner honest belly laughs on one page, then manage to wrench real emotion out of you the next. The best funny authors are adept at this switch. The worst leave you feeling queasy. And Curtis never, not ever, gives a reader a queasy feeling.

Normally I have a problem with books where characters act out-of-step with the times without any outside influence. For example, I once read a Civil War middle grade novel that shall remain nameless where a girl, without anyone in her life offering her any guidance, independently came up with the idea that “corsets restrict the mind”. Ugh. Anachronisms make me itch. With that in mind, I watched Red very carefully in this book. Here you have a boy effectively raised by a racist grandmother who is almost wholly without so much as a racist thought in his little ginger noggin. How do we account for this? Thankfully, Red’s father gives us an “out”, as it were. A good man who struggles with the amount of influence his mother-in-law may or may not have over her redheaded grandchild, Mr. Stockard is the just force in his son’s life that guides his good nature.

The preferred writing style of Christopher Paul Curtis that can be found in most of his novels is also found here. It initially appears deceptively simple. There will be a series of seemingly unrelated stories with familiar characters. Little interstitial moments will resonate with larger themes, but the book won’t feel like it’s going anywhere. Then, in the third act, BLAMMO! Curtis will hit you with everything he’s got. Murder, desperation, the works. He’s done it so often you can set your watch by it, but it still works, man. Now to be fair, when Curtis wrote Elijah of Buxton he sort of peaked. It’s hard to compete with the desperation that filled Elijah’s encounter with an enslaved family near the end. In Madman Curtis doesn’t even attempt to top it. In fact, he comes to his book’s climax from another angle entirely. There is some desperation (and not a little blood) but even so this is a more thoughtful third act. If Elijah asked the reader to feel, Madman asks the reader to think. Nothing wrong with that. It just doesn’t sock you in the gut quite as hard.

For me, it all comes down to the quotable sentences. And fortunately, in this book the writing is just chock full of wonderful lines. Things like, “An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and the same can be said of many an argument.” Or later, when talking about Red’s nickname, “It would be hard for even as good a debater as Spencer or the Holmely boy to disprove that a cardinal and a beet hadn’t been married and given birth to this boy. Then baptized him in a tub of red ink.” And I may have to conjure up this line in terms of discipline and kids: “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, but you can sure make him stand there looking at the water for a long time.” Finally, on funerals: “Maybe it’s just me, but I always found it a little hard to celebrate when one of the folks in the room is dead.”

He also creates little moments that stay with you. Kissing a reflection only to have your lips stick to it. A girl’s teeth so rotted that her father has to turn his head when she kisses him to avoid the stench (kisses are treacherous things in Curtis novels). In this book I’ll probably long remember the boy who purposefully gets into fights to give himself a reason for the injuries wrought by his drunken father. And there’s even a moment near the end when the Madman’s identity is clarified that is a great example of Curtis playing with his audience. Before he gives anything away he makes it clear that the Madman could be one of two beloved characters from Elijah of Buxton. It’s agony waiting for him to clarify who exactly is who.

Character is king in the world of Mr. Curtis. A writer who manages to construct fully three-dimensional people out of mere words is one to watch. In this book, Curtis has the difficult task of making complete and whole a character through the eyes of two different-year-old boys. And when you consider that they’re working from the starting point of thinking that the guy’s insane, it’s going to be a tough slog to convince the reader otherwise. That said, once you get into the head of the “Madman” you get a profound sense not of his insanity but of his gentleness. His very existence reminded me of similar loners in literature like Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson or The House of Dies Drear by Virginia Hamilton, but unlike the men in those books this guy had a heart and a mind and a very distinctive past. And fears. Terrible, awful fears.

It’s that fear that gives Madman its true purpose. Red’s grandmother, Mother O’Toole, shares with the Madman a horrific past. They’re very different horrors (one based in sheer mind-blowing violence and the other in death, betrayal, and disgust) but the effects are the same. Out of these moments both people are suffering a kind of PTSD. This makes them two sides of the same coin. Equally wracked by horrible memories, they chose to handle those memories in different ways. The Madman gives up society but retains his soul. Mother O’Toole, in contrast, retains her sanity but gives up her soul. Yet by the end of the book the supposed Madman has returned to society and reconnected with his friends while the Irishwoman is last seen with her hair down (a classic madwoman trope as old as Shakespeare himself) scrubbing dishes until she bleeds to rid them of any trace of the race she hates so much. They have effectively switched places.

Much of what The Madman of Piney Woods does is ask what fear does to people. The Madman speaks eloquently of all too human monsters and what they can do to a man. Meanwhile Grandmother has suffered as well but it’s made her bitter and angry. When Red asks, “Doesn’t it seem only logical that if a person has been through all of the grief she has, they’d have nothing but compassion for anyone else who’s been through the same?” His father responds that “given enough time, fear is the great killer of the human spirit.” In her case it has taken her spirit and “has so horribly scarred it, condensing and strengthening and dishing out the same hatred that it has experienced.” But for some the opposite is true, hence the Madman. Two humans who have seen the worst of humanity. Two different reactions. And as with Elijah, where Curtis tackled slavery not through a slave but through a slave’s freeborn child, we hear about these things through kids who are “close enough to hear the echoes of the screams in [the adults’] nightmarish memories.” Certainly it rubs off onto the younger characters in different ways. In one chapter Benji wonders why the original settlers of Buxton, all ex-slaves, can’t just relax. Fear has shaped them so distinctly that he figures a town of “nervous old people” has raised him. Adversity can either build or destroy character, Curtis says. This book is the story of precisely that.

Don’t be surprised if, after finishing this book, you find yourself reaching for your copy of Elijah of Buxton so as to remember some of these characters when they were young. Reaching deep, Curtis puts soul into the pages of its companion novel. In my more dreamy-eyed moments I fantasize about Curtis continuing the stories of Buxton every 40 years until he gets to the present day. It could be his equivalent of Louise Erdrich’s Birchbark House chronicles. Imagine if we shot forward another 40 years to 1941 and encountered a grown Benji and Red with their own families and fears. I doubt Curtis is planning on going that route, but whether or not this is the end of Buxton’s tales or just the beginning, The Madman of Piney Woods will leave child readers questioning what true trauma can do to a soul, and what they would do if it happened to them. Heady stuff. Funny stuff. Smart stuff. Good stuff. Better get your hands on this stuff.

On shelves September 30th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

First Sentence: “The old soldiers say you never hear the bullet that kills you.”

Like This? Then Try:

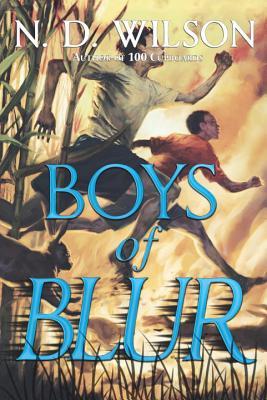

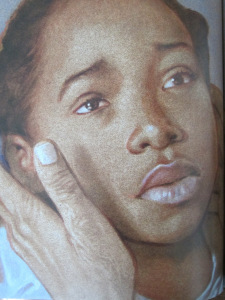

Notes on the Cover: As many of us are aware, in the past historical novels starring African-American boys have often consisted of silhouettes or dull brown sepia-toned tomes. Christopher Paul Curtis’s books tend to be the exception to the rule, and this is clearly the most lively of his covers so far. Two boys running in period clothing through the titular “piney woods”? That kind of thing is rare as a peacock these days. It’s still a little brown, but maybe I can sell it on the authors name and the fact that the books look like they’re running to/from trouble. All in all, I like it.

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/19/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mysteries,

Reviews,

Best Books,

middle grade mysteries,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

Clarion Books,

Kate Milford,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 mysteries,

2015 Newbery contender,

Add a tag

Greenglass House

Greenglass House

By Kate Milford

Clarion Books (an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-544-05270-3

Ages 9-12

On shelves August 26th

When I was a kid I had a real and abiding love of Agatha Christie. This would be around the time when I was ten or eleven. It wasn’t that I was rejecting the mysteries of the children’s book world. I just didn’t have a lot to choose from there. Aside from The Westing Game or supernatural ghostly mysteries sold as Apple paperbacks through the Scholastic Book Fair, my choices were few and far between. Kids today have it better, but not by much. Though the Edgar Awards for best mystery fiction do dedicate an award for young people’s literature, the number of honestly good mystery novels for the 9-12 set you encounter in a given year is minimal. When you find one that’s really extraordinary you want to hold onto it. And when it’s Kate Milford doing the writing, there’s nothing for it but to enjoy the ride. A raconteur’s delight with a story that’ll keep ‘em guessing, this is one title you won’t want to miss.

It was supposed to be winter vacation. Though Milo’s parents run an inn with a clientele that tends to include more than your average number of smugglers, he can always count on winter vacation to be bereft of guests. Yet in spite of the awful icy weather, a guest appears. Then another. Then two more. All told more than five guests appear with flimsy excuses for their arrival. Some seem to know one another. Others act suspiciously. And when thefts start to take place, Milo and his new friend Meddy decide to turn detective. Yet even as they unravel clues about their strange clientele there are always new ones to take their places. Someone is sabotaging the Greenglass House but it’s the kids who will unmask the culprit.

To my mind, Milford has a talent that few authors can boast; She breaks unspoken rules. Rules that have been dutifully followed by children’s authors for years on end. And in breaking them, she creates stronger books. Greenglass House is just the latest example. To my mind, three rules are broken here. Rule #1: Children’s books must mostly be about children. Adults are peripheral to the action. Rule #2: Time periods are not liquid. You cannot switch between them willy-nilly. Rule #3: Parents must be out of the picture. Kill ‘em off or kidnap them or make them negligent/evil but by all means get rid of them! To each of these, Milford thumbs her proverbial nose.

Let’s look at Rule #1 first. It is worth noting that with the exception of our two young heroes, the bulk of the story focuses on adults with adult problems. It has been said (by me, so take this with a grain of salt) that by and large the way most authors chose to write about adults for children is to turn them into small furry animals (Redwall, etc.). There is, however, another way. If you have a small innocuous child running hither and thither, gathering evidence and spying all the while, then you can talk about grown-ups for long periods of time and few child readers are the wiser. If I keep mentioning The Westing Game it’s because Ellen Raskin did very much what Milford is doing here, and ended up with a classic children’s book in the process. So there’s certainly a precedent.

On to Rule #2. One of the remarkable things about Kate Milford as a writer is that she can set a book in the present day (there is a mention of televisions in this book, so we can at least assume it’s relatively recent) and then go and fill it with archaic, wonderful, outdated technology. A kind of alternate contemporary steampunk, if there is such a thing. In an era of electronic doodads, child readers are going to really get a kick out of a book where mysterious rusted keys, old doorways, ancient lamps, stained green glass windows, and other old timey elements give the book a distinctive flavor.

Finally, Rule #3. This was the most remarkable of choices on Milford’s part, and I kept reading to book to find out how she’d get away with it. Milo’s parents are an active part of his life. They clearly care for him, periodically checking up on his throughout the story, but never interfering with his investigations. Since the book is entirely set in the Greenglass House, it has the feel of a stage play (which, by the way, it would adapt to BRILLIANTLY). That means you’re constantly running into mom and dad, but they don’t feel like they’re hovering. This is partly aided by the fact that they’re incredibly busy. So, in a way, Milford has discovered a way of removing parental involvement without removing parental care. The kids are free to explore and solve crimes and the adult gatekeepers reading this book are comforted by the family situation. A rarity if ever there was one.

But behind all the clues and ghost stories and thefts and lies what Greenglass House really is is the story of a hero’s journey. Milo starts out a soft-spoken kiddo with little faith in his own abilities. Donning the mantle of a kind of Dungeons & Dragons type character named Negret, he taps into a strength that he might otherwise not known he even had. There is a moment in the book when Milo starts acting with more confidence and actually thinks to himself, “And I didn’t even have to use Negret’s Irresistible Blandishment . . . I just did it.” Milo’s slow awakening to his own strengths and abilities is the heart of the novel. For all that people will discuss the mystery and the clues, it’s Milo that holds everything together.

Much of his personality is embedded in his identity as an adopted kid too. I love the mention of “orphan magic” that Milford makes at one point. It’s the idea that when something is sundered from its attachments it becomes more powerful in the process. At no point does Milford ever downplay the importance of the fact that Milo is adopted. It isn’t a casual fact that’s thrown in there and then forgotten. For Milo, the fact that he was adopted is part of who he is as a person. And coming to terms with that is part of his journey as well. Little wonder that he gathers such comfort from learning about orphan magic and its potential.

I’m looking at my notes about this book and I see I’ve written down little random facts that don’t really fit in with this review. Things like, “I did wonder if Milo’s name was a kind of unspoken homage to the Milo of The Phantom Tollbooth. And, “The book’s attitude towards smuggling is not all that different from, say, Danny, the Champion of the World’s attitude towards poaching.” And, “I love the vocabulary at work here. Raconteur. Puissance.” There is a lot a person can say about this book. I should note that there is a twist that a couple kids may see coming. It is, however, a fair twist and one that doesn’t cheat before you get to it. For the most part, Milford does a divine job at writing a darned good mystery without sacrificing character development and deeper truths. A great grand book for those kiddos who like reading books that make them feel smart. Fun fun fun fun fun.

On shelves August 26th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

First Sentence: “There is a right way to do things and a wrong way, if you’re going to run a hotel in a smugglers’ town.”

Professional Reviews:

Interviews: Milford reveals all with The Enchanted Inkpot.

Misc:

- In lieu of an Author’s Note, Kate provides some background information on Milo and adoption that is worthy additional reading here.

- Cover artist Jaime Zollars discusses being selected to illustrate the book jacket here.

- Discover how the book came from a writing prompt here.

Sloooooowly the predictions begin. As I post this I’m hitting the sweet spot right between Book Expo and the annual American Library Association conference. Which is to say, this is the moment in time when some folks have seen the fall galleys from BEA while other folks are about to see them at ALA. On maternity leave, I am hampered significantly by what I see. Most galleys are being sent to my workplace where they are out of my reach. So while I’ve still seen a wide swath of things, I know that there are books I’m missing. The fall prediction edition will be more complete, I am certain. Plus, by that time we’ll see Heavy Medal and Calling Caldecott back up and running and predicting as well.

Meantime, I’m not the only one making predictions these days. If you missed it, Travis Jonker did a heckuva great post when he predicted this year’s New York Times Best Illustrated. These are books that might not be eligible for the Caldecott but that would be complete and utter contenders under different circumstances. Worth your glance.

And now, some thoughts on the matter!

2015 Newbery Predictions

The Night Gardener by Jonathan Auxier

I’ve been very happy with the buzz surrounding Auxier’s latest. When I reviewed it back in March I suspected that it had fine, outstanding qualities worthy of award consideration. That suspicion has since been confirmed several times over by the multiple starred reviews and the online conversations I’ve observed. Typical of the dark fantasy trend in middle grade in 2014 (aside from Snicker of Magic, everything’s pretty gloom and doom this year) Auxier’s book does what Doll Bones did last year, blending classic horror elements with deeper themes and questions for young readers. His is a book that asks kids to question the nature of storytelling and lying (another 2014 trend, and a prevalent one that I intend to explore more thoroughly). At the very least, I predict that this will be showing up on many many Mock Newbery lists this year.

Curiosity by Gary L. Blackwood

This is actually not garnering the buzz I’d expect of it this year. Surprising since the release of a new Blackwood is a cause for celebration. My suspicion is that the man has been out of the middle grade field for so long that new crops of young librarians are unaware of his work. This is a true pity since Curiosity hits all the pleasure points of a Brian Selznick story. With a killer cover and some superb writing, my hope is that the buzz is just on a low-boil and will be turned up significantly as we near the award season. Perhaps this is my dark horse candidate this year, but I don’t think you should count it out. It could definitely pull a Paperboy or Breaking Stalin’s Nose surprise win out of its hat.

Absolutely Almost by Lisa Graff

For years I’ve wanted a Lisa Graff book to make it onto my prediction lists, but every time there was just something holding me back. No longer. The remarkable thing about Absolutely Almost is that it dares not to be remarkable. Or rather, it celebrates kindness over being special. I’ll keep my thoughts to myself for the review I’ll write of it but Graff has accomplished here is something incredibly difficult. Plus I love the idea of a major award going to a book that celebrates Captain Underpants like this one does.

The Nightingale’s Nest by Nikki Loftin

Another dark horse, and maybe one of the more divisive books on this list. Loftin makes a lunge for magical realism with her story, which is a very difficult thing to do in middle grade novels. The controversy surrounding it concerns The Emperor and what he did or did not do to the story’s heroine. To my mind, any child reader who goes through this story will only recognize that he stole the girl’s voice by recording it. End of story. But because this book can be read very differently by adults vs. children, that may inhibit its chances. Only time will tell. The writing, few can argue, is superb.

The Greenglass House by Kate Milford

One of my favorite books of the year. Pure pleasure reading through and through. I’ve heard it described as “Clue meets The Westing Game” and that’s not too far off. We haven’t had a Westing Game kind of book win a Newbery in a while, unless you count When You Reach Me. It would be awfully nice for a mystery to win once more, and Milford’s talents at creating a whole and complete world within her pages is stellar. Definitely a contender.

West of the Moon by Margi Preus

There are only two books out this year that I think are surefire Newbery contenders, and this is one of them (you’ll meet the other soon). Preus is a marvel. This book, again, taps equally into darkness and storytelling vs. lies while also managing to pluck all the use out of fantasy and yet remain fairly historical fiction-y. It’s a quick read and a gripping one. Additional Bonus: Lockjaw!

Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson

Good buzz is surrounding Wilson’s latest, which is excellent. I’ve already felt a little pushback to it, but the strong writing is working very well in its favor. It’s not a sure thing, but if any Wilson book can finally make a decent lunge for the Newbery it is this. Already I can predict that Heavy Medal will have a hard time with it (I would LOVE to be mistaken about this, though). Plus it probably has the best book trailer of the year thus far.

brown girl dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

The frontrunner, as far as I can tell. No question. There is nothing one can call a sure thing when it comes to Newbery or Caldecott books. Heck, a couple of years ago I would have said that One Crazy Summer was a shoo-in. Shows what I know. That said, if this book does not win the Newbery proper then there will be blood in the streets. Gushing torrents of scarlet red blood. In a year of #WeNeedDiverseBooks what a capper it would be to give the Award to what is, not only, the best book of the year but also one that stands as a necessary piece of African-American history. Not that the committee can think in those terms. All that they can do is say whether or not the book is one of the most distinguished of the year. Spoiler Alert: It is.

That’s what I think in terms of the frontrunners. But there are plenty of other books that people are discussing. Consider, for example, Rain, Reign by Ann M. Martin. She won a Newbery Honor years ago. Will she be able to recapture the magic with her latest? Maybe, but not with this particular book. It’s nicely done but as a woman hepped up on postpartum hormones, it tried to make me cry and didn’t quite get there. That’s telling. The Fourteenth Goldfish by Jennifer L. Holm is another fantastic and fun read (and pure science fiction, which is very rare indeed). It feels like a slightly younger When You Reach Me, which is a fine and fancy pedigree. But Newbery? I didn’t feel it. The Riverman by Aaron Starmer was definitely one I was thinking of when I first read it, but when I heard it was the first in a series that changed my interpretation of the ending. Will the committee feel the same way? The writing is, after all, fabulous. Upside Down in the Middle of Nowhere by Julie T. Lamana was a book I loved earlier in the year. I still love it, though in the wake of other strong contenders I’m not sure if it’ll make it to the award finish line. And, of course, there is Snicker of Magic by Natalie Lloyd. Forget what I said about Nightingale’s Nest. THIS is the most divisive book of 2014. The writing is very accomplished and it’s got great lines. Plus it’s nice to see something But Newbery? To win it’ll have to convince the committee that the (totally unnecessary and occasionally infuriating) cutesy parts are overwhelmed by the good writing. Its win relies entirely on the tone of the committee. I don’t envy them the debates.

Phew! Moving on . . .

2015 Caldecott Predictions

Um . . no idea. Honestly, I haven’t felt this out to sea in terms of the Caldecott in years. I’m just not feeling it this year. There are some superb books but surprisingly few of them grab me by the throat and throttle me while screaming “CALDECOTT!!!!” in my ear. I always fall apart on Caldecott predictions anyway. Last year at this time I only mentioned two of the eventual winners, not even mentioning the other two (and HOW on earth did I fail to mention the glorious Flora and the Flamingo, I ask you?!?). This year I just keep coming back to the books I mentioned in my spring prediction edition. Fortunately, a couple additional books caught my jaded eye . . .

Bad Bye, Good Bye by Deborah Underwood, ill. Jonathan Bean

Bean wowed the world last year with his Building Our House, a winner of the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award. But you know what Caldecott committees really like? Variety. That’s why his latest change of style is so exciting. The beautiful simplicity of Underwood’s text, which manages to tell a complete story with a minimum of words, is matched page for page by Bean’s art. The pairing results in a particularly strong product and since Caldecott committees are extraordinarily interested in books that pair art and text well, it seems to me we may have a winner on our hands here.

A Dance Like Starlight by Kristy Dempsey, ill. Floyd Cooper

A Floyd Cooper. An honest-to-god Floyd Cooper prediction. Considering the man’s output, this may strike some as surprising. No one ever contests that he’s accomplished but he’s one of those perpetual Caldecott bridesmaids never brides (see my post on such folks here). It doesn’t matter how gorgeous his art is, he gets passed by time after time. Except . . . something about this book is different. My librarians, for one thing, who have always been Cooper-tepid are GAGA over this. It’s not just the fact that the text manages to do the whole Live Your Dream storyline without getting cheesy. There’s some stellar art at work. This is a bad scan, but if this book does well I think it’ll be because of this image:

Viva Frida by Yuyi Morales, photographs by Tim O’Meara

Speaking of always bridesmaids . . . but this book. I mean, just wow. Not that a Caldecott committee has ever, to the best of my knowledge, awarded three-dimensional art (scholars, correct me!). But that’s the wonder of this book. It isn’t JUST three-dimensional art, but two-dimensional as well. The book itself celebrates the very concept of being an artist (a swell thing for a Caldecott committee to reward) and as I learned last year, Ms. Morales has residency here in the States so she certainly could win this thing. Some folks don’t like that it isn’t a straight biography but something a little more artistic and esoteric. Pfui to them, sez I. You simply cannot read this and not find it stunning.

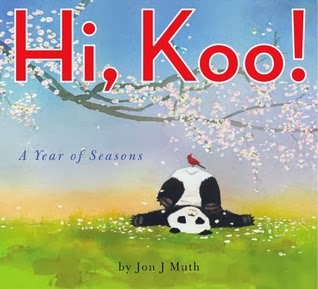

Hi, Koo! A Year of Seasons by Jon J. Muth

Never count out a Muth. Though this book has far less lofty ambitions than his past Caldecott win, it has heart and lovely watercolors. This could easily be sidelined altogether, or go for the big gold. Certainly hard to say at this point.

Three Bears in a Boat by David Soman

It’s my personal #1, which makes me worry for its future. When I get emotional about a book I find it sometimes hampers my view of its award chances. That said, no one doubts the sheer beauty of the art here. Soman’s always been someone to watch, even when working on something as popular as the Ladybug Girl series. Can he win hearts and minds with bears? I say yes.

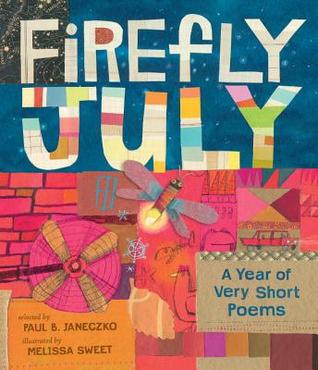

Firefly July and Other Very Short Poems selected by Paul B. Janeczko, illustrated by Melissa Sweet

We know Sweet is automatic Caldecott bait, but you’re never quite sure which of her books will attract the committee. This book isn’t afraid to be long and strong on the poetry. I’ve heard grumbles in some quarters that the poems don’t always necessarily pair with one season or another, but that’s nothing against the art. Still, it might affect its chances in the end.

Grandfather Gandhi by Arun Gandhi and Bethany Hegedus, illustrated by Evan Turk

If any debut deserves love it’s this one. A remarkable combination of art and heart, with different styles and a heckuva great take on the subject matter. Turk’s one to watch and this book is already one of the year’s favorites. Even if it doesn’t win, it bodes well for the artist’s future.

In terms of books getting some nice buzz, I’ve heard some folks mentioning The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend by Dan Santat. I love me a good Santat and Dan certainly poured his heart and soul into this one. So why don’t I think it’s a surefire winner? Hard to say. The art is certainly nice enough. Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch by Anne Isaacs, illustrated by Kevin Hawkes hasn’t shown up on a lot of lists, but Anne Isaacs has a way of writing books that catch the eye of award committees. My own librarians are very taken with this latest effort, and Hawkes should at least get a mention if only for the sheer disgustingness of his desperadoes. Baby Bear by Kadir Nelson is one of those books that should, by rights, be a Caldecott contender. Indeed there are some stirring images here. Unfortunately there’s something off about this particular Nelson book. It’s hard to pinpoint but it lays in the art. Nelson’s due for a big gold someday. This, however, probably won’t be “the one”. Breathe by Scott Magoon is absolutely lovely and I would love Magoon to get an award one of these days. It definitely belongs to the whale trend of 2014. Will it get an award? It may be too subtle for that. We’ll see. Finally, Sparky! by Jenny Offill, illustrated by Chris Appelhans, is the book getting a lot of the buzz. I loved the story and the art but while I found it lovely and funny by turns I didn’t feel the award hum at work. I think Appelhans is definitely one to watch. You’re just going to have to keep watching.

For additional thoughts, be sure to check out the Goodreads lists of Newbery 2015 and Caldecott 2015 to see what the masses prefer this year.

So! What did I miss?

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/2/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Best Books,

Jacqueline Woodson,

verse novels,

multicultural fiction,

middle grade historical fiction,

fictional memoirs,

multicultural middle grade,

New York books,

middle grade verse novels,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Add a tag

brown girl dreaming

brown girl dreaming

By Jacqueline Woodson

Nancy Paulsen Books (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISBN: 978- 0399252518

Ages 9-12

On shelves August 28th

What does a memoir owe its readers? For that matter, what does a fictionalized memoir written with a child audience in mind owe its readers? Kids come into public libraries every day asking for biographies and autobiographies. They’re assigned them with the teacher’s intent, one assumes, of placing them in the shoes of those people who found their way, or their voice, or their purpose in life. Maybe there’s a hope that by reading about such people the kids will see that life has purpose. That even the most high and lofty historical celebrity started out small. Yet to my mind, a memoir is of little use to child readers if it doesn’t spend a significant fraction of its time talking about the subject when they themselves were young. To pick up brown girl dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson is to pick up the world’s best example of precisely how to write a fictionalized memoir. Sharp when it needs to be sharp, funny when it needs to be funny, and a book that can relate to so many other works of children’s literature, Woodson takes her own life and lays it out in such a way that child readers will both relate to it and interpret it through the lens of history itself. It may be history, but this is one character that will give kids the understanding that nothing in life is a given. Sometimes, as hokey as it sounds, it really does come down to your dreams.

Her father wanted to name her “Jack” after himself. Never mind that today, let alone 1963 Columbus, Ohio, you wouldn’t dream of naming a baby girl that way. Maybe her mother writing “Jacqueline” on her birth certificate was one of the hundreds of reasons her parents would eventually split apart. Or maybe it was her mother’s yearning for her childhood home in South Carolina that did it. Whatever the case, when Jackie was one-years-old her mother took her and her two older siblings to the South to live with their grandparents once and for all. Though it was segregated and times were violent, Jackie loved the place. Even when her mother left town to look for work in New York City, she kept on loving it. Later, her mother picked up her family and moved them to Brooklyn and Jackie had to learn the ways of city living versus country living. What’s more, with her talented older siblings and adorable baby brother, she needed to find out what made her special. Told in gentle verse and memory, Jacqueline Woodson expertly recounts her own story and her own journey against a backdrop of America’s civil rights movement. This is the birth of a writer told from a child’s perspective.