By Simon Eliot

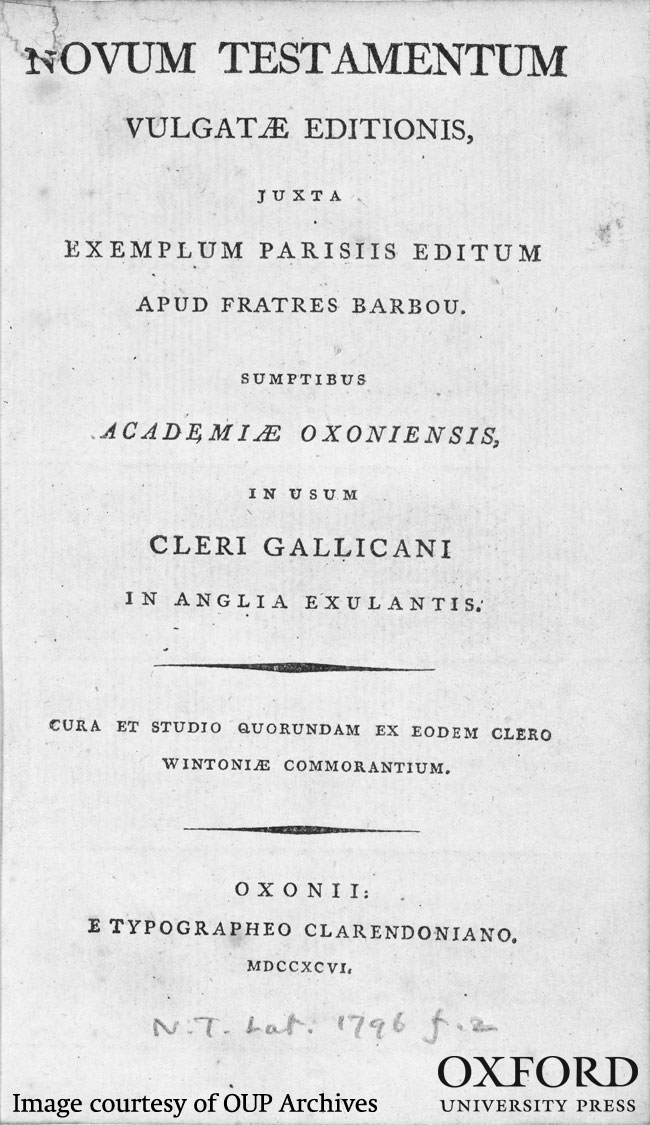

With the French Revolution creating a wave of exiles, the Press responded with a very uncharacteristic publication. This was a ‘Latin Testament of the Vulgate Translation’ for emigrant French clergy living in England after the Revolution. In 1796, the Learned (not the Bible) side of the Press issued Novum Testamentum Vulgatae Editionis: Juxta Exemplum Parisiis Editum apud Fratres Barbou. The title page went on to declare that it had been printed at the University of Oxford for the use of French clerics who were exiled in England. This edition was based, as the title makes clear, on editions published by the Barbou brothers, which had been printed at Paris from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. This particular edition had been overseen by a number of French priests ‘living in Winchester’. The reference is to the King’s House in Winchester which, until the government converted it into barracks in 1796, was home to around 600 exiled French clergy; these were later re-housed in Reading and in Thame in the Thames valley.

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

A total of some 4,000 copies of this edition were printed: “That 2,000 Copies of the Lat. Vulgate Testament (besides the additional 2,000 printed by order of the Marquis of Buckingham) be forwarded to the Bishop of St . Pol de Leon to be distributed under his direction … and the remainder sold at two shillings each.”

Though partly an exercise in charity, it was clearly anticipated that this New Testament might also be considered a commercial proposition. The published volume appears to be a particular form of duodecimo (strictly 12o in 6s, half-sheet imposition; the paper carried a watermarked date of ‘1794’) of 473 pages with a four-page preface by the Bishop addressed to ‘Meritissime Domine Vice-Cancellarie’, in which he expressed his gratitude to the University of Oxford for its support. At the end of the text there is a brief chronological table of New Testament events, followed by an ‘Index Geographicus’. A final unnumbered leaf carries a list of errata (29 in all) which reflected a rather different approach to that adopted by the Bible Side of the Press when issuing its editions of the King James Version of the New Testament. The latter were subjected to rigorous proof reading and re-reading in order to ensure that the word of God was as free from errors as was humanly possible. This edition of a Latin text, produced in extraordinary circumstances for the consumption of mostly foreign readers, was clearly a very different kettle of fish. Additionally, in printing this edition on the Learned Side rather than the Bible Side of the Press, the Delegates culturally quarantined the production of the Vulgate text and avoided any political or religious problems that might have arisen had the privileged side of the Press undertaken it. That the very peculiar and extreme circumstances which produced this anomaly were not to be repeated was made clear 99 year later when, it having been suggested in 1895 that the Press should produce a Roman Catholic Bible, the Delegates responded that they did not ‘think it desirable that such a work should be issued with the University Press Imprint’.

Later, as the threat from Napoleonic France increased, the Press recorded certain exceptional payments in its annual accounts. These accounts included many forms of overhead costs, some a constant feature of the Press’s outgoings, such as the cost of coals and firewood (£10.17.6 in 1800) or ‘taxes to Magdalen Parish’ (£8.16.0 in the same year). Others were temporary and related to the troubled times in which they were paid. The 1805-6 accounts list the payment of a ‘Militia Tax’ of 8s6d, which went up to 17s4d in the following year. Having missed the subsequent year, the Press paid two militia rates in 1808-9 amounting to £2-7-8. In 1812-3 the rate was £1-6-0, dropping to 13s in 1813-4 before vanishing from the accounts as the threat represented by Napoleon disappeared after the battle of Waterloo.

Simon Eliot is Professor of the History of the Book in the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London. He is general editor of The History of Oxford University Press, and editor of its Volume II 1780-1896.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Read previous blog posts about the history of Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A Vulgate New Testament printed for the use of exiled French clergy, 1796. (Bodleian, N.T.Lat. 1796 f.2, 159 x 96mm). From the History of Oxford University Press. Courtesy of OUP Archives. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Press stands firm against the French Revolution and Napoleon appeared first on OUPblog.