new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: cdc, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: cdc in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 4/11/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

second edition,

Barry S. Levy,

Victor W. Sidel,

*Featured,

Health & Medicine,

Gun Violence,

Social Injustice and Public Health,

Center for Disease Control and Prevention,

congressional ban on CDC gun violence research,

gun injuries research,

gun-related morbidity and mortality,

US gun control,

Books,

CDC,

public health,

firearms,

Add a tag

Imagine that there is a disease that claims more than 30,000 lives in the United States each year. Imagine that countless more people survive this disease, and that many of them have long-lasting effects. Imagine that there are various methods for preventing the disease, but there are social, political, and other barriers to implementing these preventive measures.

The post Lift the congressional ban on CDC firearm-related deaths and injuries research appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 12/31/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

earthquake,

CDC,

natural disaster,

Place of the Year,

nepal,

POTY,

humanitarian aid,

*Featured,

Yellow Book,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

travel medicine,

CDC Health Information for International Travel 2016,

Place of the Year 2015,

POTY 2015,

aid workers,

Megan O’Sullivan,

Ronnie Henry,

Add a tag

Just before noon on 25 April 2015, a violent 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Nepal, killing almost 9,000 people and injuring more than 23,000. Hundreds of aftershocks followed. Entire villages were razed, destroying communities and leaving hundreds of thousands of people homeless.

The post Traveling to provide humanitarian aid: lessons from Nepal appeared first on OUPblog.

By: JulieF,

on 9/29/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

CDC Health Information for International Travel 2016,

Gary W. Brunette,

international outbreak,

medical care abroad,

traveling health care workers,

world travel infographic,

Books,

Multimedia,

CDC,

international travel,

Infographics,

immunizations,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

Add a tag

Are you planning a trip to Brazil, Cambodia, The Dominican Republic, Haiti, or another destination that requires immunizations in advance of your arrival? Are you a health care worker, about to travel to a destination currently dealing with an epidemic or outbreak?

The post Preparing for world travel [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 8/5/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Current Affairs,

CDC,

world health organization,

west africa,

pandemics,

What Everyone Needs To Know,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

WENTK,

Ebola,

Peter C. Doherty,

Fruit bats,

Public Health Services,

virus infection,

hendra,

Add a tag

By Peter C. Doherty

The Ebola outbreak affecting Guinea, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and now Liberia is the worst since this disease was first discovered more than 30 years back. Between 1976 and 2013 there were less than 1,000 known infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC), March to 23 July 2014 saw 1201 likely cases and 672 deaths. The ongoing situation for these four West African countries is extremely dangerous, and there are fears that it could spread more widely in Africa. The relatively few intensive care units are being overwhelmed and the infection rate is likely being exacerbated by the fact that some who become ill are, on hearing that there is no specific treatment, electing to die at home surrounded by their family. The big danger is that very sick patients bleed, and body fluids and blood are extremely infectious.

American Patrick Sawyer, who was caring for his ill sister in Nigeria, has died of the disease. Working with the Christian AID Agency Samaritan’s Pulse in Monrovia, Dr Kent Brantly from Texas and Nancy Writebol from North Carolina are thought to have been infected following contact with a local staff member. Both are symptomatic but stable as I write this (July 31).

Ebola cases are classically handled by isolation, providing basic fluid support, and “barrier nursing”. Ideally, that means doctors and nurses wear disposable gowns, quality facemasks, eye protection and (double) latex gloves. That’s why it is so dangerous for patients to be cared for at home. And, even when professionals are involved, the highest incidence of infection is normally in health care workers. A number of doctors have died in the current outbreak. If there’s any suspicion that travelers returning from Africa may be infected, it is a relatively straightforward matter in wealthy, well-organized countries like the USA to institute appropriate isolation, nursing, and control. That’s why the CDC believes that the threat to North America is minimal. As for so many issues, the problem in Africa is exacerbated by poverty and the social disruption that goes with a lack of basic resources.

The fight against Ebola in West Africa… 4 months after the first case of Ebola was confirmed in Guinea, more than 1200 people have been infected across 3 West African countries. This biggest Ebola outbreak ever recorded requires an intensification of efforts to avoid it from spreading further and claiming many more lives. Photo credits: ©EC/ECHO/Jean-Louis Mosser. EU Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection. CC BY-ND 2.0 via European Commission DG ECHO Flickr.

Given that this disease is not a constant problem for humans, where does it hide out? Fruit bats are thought to be the natural and asymptomatic reservoir, though, unlike the hideous and completely unrelated Hendra and Nipah viruses that have caused somewhat similar symptoms in Australia and South East Asia, there is no Ebola virus in bats from those regions. And, while Hendra and Nipah are lethal for horses and pigs respectively, Ebola is killing off the great apes including our close and endangered primate relatives, the Chimpanzees and Gorillas. The few human Hendra infections have been contracted from sick horses that were, in turn, infected from fruit bats. An “index” (first contact) human Ebola case could result from exposure to bat droppings, or from killing wild primates for “bush meat” a practice that is, again, exacerbated by poverty. And, unlike Hendra, Ebola is known to spread from person to person.

The early Ebola symptoms of nausea, fever, headaches, vomiting, diarrhea, and general malaise are not that different from those characteristic of a number of virus infections, including severe influenza. But Ebola progresses to cause the breakdown of blood vessel walls and extensive bleeding. Also, unlike the fast developing influenza, the Ebola incubation period can be as long as two to three weeks, which means that there must be a relatively long quarantine period for suspected contacts. Fortunately, and unlike influenza and the hideous (fictional) bat-origin pathogen depicted in the recent movie Contagion, Ebola is, in the absence of exposure to contaminated body fluids, not all that infectious. Unlike most such Hollywood accounts, Contagion is relatively realistic and describes how government public health laboratories like the CDC operate. It’s worth seeing, and has been described as “the thinking person’s horror movie.”

Along with comparable EEC agencies and the WHO, the CDC currently has about 20 people “on the ground” in West Africa. Other support is being provided by organizations like Doctors Without Borders, the International Red Cross, and so forth. At this stage, there are no antiviral drugs available and no vaccine, though there are active research programs in several institutions, including the US NIH Vaccine Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Though there is no product currently available, it would be a big plus if all African healthcare workers could be vaccinated against Ebola. Apart from develop specific “small molecule” drugs, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that bind to proteins on the surface of the virus may be useful for emergency treatment and to give those in contact “passive” protection for three or four weeks. Such “miraculous mAbs” can now be developed and produced quickly, though they are very expensive.

What is being done? Neighboring African countries are closing their borders. International agencies and governments are providing more professionals and other resources to help with treatment and tracking cases and contacts. Global companies have been withdrawing their workers and all nations are maintaining a close watch on air travelers who are arriving from, or have recently been in, these afflicted nations.

What is this Ebola catastrophe telling us? In these days of global cost-cutting, we must keep our National and State Public Health Services strong and maintain the funding for UN Agencies like the OIE, the WHO, and the FAO. High security laboratories (BSL4) at the CDC, the NIH and so forth are a global resource, and their continued support along with the training and resourcing of the courageous, dedicated physicians and researchers who work with these very dangerous pathogens, is essential. Humanity is constantly challenged by novel, zoonotic viruses like Ebola, Hendra, Nipah, Sin Nombre, SARS, and MERS that emerge out of wildlife reservoirs, with the likelihood of such events being increased by extensive forest clearing, ever increasing population size and rapid air travel. We must be indefatigably watchful and prepared. Throughout history, nature is our worst bioterrorist.

Peter C. Doherty has appointments at the University of Melbourne, Australia, and St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis. He is the 2013 author of Pandemics: What Everyone Needs to Know, which looks at the world of pandemic viruses and explains how infections, vaccines and monoclonal antibodies work . He shared the 1996 Nobel Prize for Physisology or Medicine for his discoveries concerning “The Cellular Immune Defense”.

What Everyone Needs to Know (WENTK) series offers a balanced and authoritative primer on complex current event issues and countries. Written by leading authorities in their given fields, in a concise question-and-answer format, inquiring minds soon learn essential knowledge to engage with the issues that matter today.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How threatened are we by Ebola virus? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 4/22/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

heart health,

American Heart Association,

sodium,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

American Journal of Hypertension,

cardiology,

Niels Graudal,

intake,

Journals,

CDC,

Hypertension,

salt intake,

Add a tag

The American Journal of Hypertension (AJH) recently published the findings of a comprehensive meta-analysis monitoring health outcomes for individuals based on their daily sodium intake. The results were controversial, seemingly confirming what many notable hypertension experts have begun to suspect in recent years: that levels of daily sodium intake recommended by governmental agencies like the CDC are far too low, perhaps dangerously so.

Media outlets were quick to broadcast the findings, and the response from the CDC and organizations like the American Heart Association were much the same as in the past, dismissing the analysis, without pointing to specifics, as relying on “faulty methodology” and “flawed data.”

We recently spoke to Dr. Niels Graudal, lead author of the meta-analysis published in AJH, to understand, among other things, the details of his research and his opinion on the reaction of governmental health agencies to new findings on sodium intake.

Could you start by talking to us about the nature of a meta-analysis? What about your meta-analysis makes its findings more valid than, say, a single, localized study?

Population studies are accepted in health science as a means to define associations between health-factors. For instance, the associations between blood pressure, cholesterol, and mortality have been defined by such studies. Meta-analyses integrate the results from many individual studies to provide an average of the association of the “risk factor” to outcome. Such analyses help to reach a consensus, and constitute the core of the Cochrane Collaboration, which systematically organizes medical research information on the basis of scientific evidence.

Was there a common methodology among the studies included in your meta-analysis?

In population studies on sodium intake, the individually-measured sodium intake is used to categorize the participants in groups of low, intermediate, and high sodium intake. The groups are followed for years, while mortality (death rate) and morbidity (disease rate) in the different groups are recorded. Successively, the association between sodium intake and mortality/morbidity is calculated.

What are some possible obstacles encountered in population studies like this?

There are factors which could bias the result in a wrong direction, so-called “confounders.” For instance, sodium intake typically increases with energy intake. Sick participants with a low energy intake may therefore eat less sodium than healthy people, and overweight participants predisposed to diabetes and cardiovascular disease may eat more sodium than healthy people. Therefore, the energy intake is a confounder, which could explain a potential increased mortality in participants with a low and a high sodium intake. However, there are statistical methods that allow us to correct for such confounders in order to ensure for accurate findings; such methods are used in almost all such studies, and have been for many years.

What were the specific findings of your meta-analysis on sodium intake?

Perhaps most importantly, the implications of these findings are that the present recommendation from the CDC that individuals should reduce sodium intake to below 2300 mg/day is too restrictive, and that the majority (about 95%) of the global population presently eat sodium within the safest range (2,645-4,945 mg/day) and therefore have no need to alter their intake.

Our

present analysis showed that both high sodium intake and low sodium intake were associated with increased mortality when compared with the present usual sodium intake of most individuals worldwide, which is between 2,645 and 4,945 mg per day. In spite of the fact that sodium intake is somewhat difficult to measure precisely, the signal from the nearly 275,000 participants we looked at was abundantly clear.

Perhaps most importantly, the implications of these findings are that the present recommendation from the CDC that individuals should reduce sodium intake to below 2300 mg/day is too restrictive, and that the majority (about 95%) of the global population presently eat sodium within the safest range (2,645-4,945 mg/day) and therefore have no need to alter their intake.

How did you account for those participants in your analysis that were already suffering from, say, hypertension or obesity? Might they have affected the findings in some way?

When we excluded groups of populations with diseases from our analysis and only included healthy populations, which were random samples of the general population and within which multiple statistical adjustments for confounders had been performed, the results concerning low sodium intake were even more significant, indicating that confounders could not have affected the outcome of our analysis.

Is your meta-analysis the first scientific research to suggest that extremely low levels of sodium intake like those promoted by the CDC may actually be associated with negative health outcomes?

Actually, a 1984 paper published in the journal Science questioned the wisdom of population-wide sodium intake reduction on the basis of an investigation of about 10,000 participants. The FDA immediately published a high-profile response in The New York Times, claiming that the findings were likely the result of a statistical fluke or “something wrong with the analysis.” This immediate move to quell any dissenting evidence seems to have governed the debate ever since.

More recently, though, a population study published while our meta-analysis was under review showed results very similar to ours. Two of the individual studies (1, 2) included in our analysis also concluded that there was a “U” shaped correlation between sodium intake and mortality (increased risks at very low and high doses). For the record, excluding these two studies from our analysis did not change our results. In the past year, then, four recent studies have independently confirmed increased risks associated with both high and low sodium intakes, and suggest that the present recommendation of less than 2,300 mg/day is in conflict with available science.

What are the arguments against research like this?

Often, health organizations will attempt to call into question researchers’ objectivity by labeling them biased agents of the food industry. In a recent response to a paper showing that the majority of the world’s populations had a salt intake significantly above the recommended 2,300 mg/day, representatives of the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Action on Salt and Health (WASH) accusatorily asked, “why has the food and beverage industry mounted yet another campaign to try to resist beneficial changes, either directly or indirectly through their academic voices?”

Sometimes agencies will willfully misinterpret findings. In a short commentary to the recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on sodium intake in populations, nine CDC employees quoted the IOM report as follows: “When it comes to sodium intake levels <2,300mg per day… the committee found insufficient and inconsistent evidence regarding the benefit or harm in certain population subgroups (e.g., individuals with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or preexisting cardiovascular disease)”. However, the actual quote from the study was this: “science was insufficient and inadequate to establish whether reducing sodium intake below 2,300 mg/d either decreases or increases CVD risk in the general population.”

Often, they claim that our data and methods are somehow flawed, though they rarely cite specific instances. In a response to our present meta-analysis, the American Heart Association (AHA) stated that the analysis relied on “flawed data and should not change the way anyone looks at sodium.” They went on to say that:

“…those studies were poorly designed to examine the relationship between sodium intake and mortality, and the findings fail to take into account well-established evidence about sodium intake. Other problems with the new study included unreliable measurements of sodium intake and an overemphasis on studying sick people rather than the general population.”

This is a small selection of the arguments which have been raised for years by representatives of public institutions (WHO, FDA, NIH, CDC, AHA) in response to scientific investigations that don’t agree with their population-wide sodium reduction agenda.

So that we can avoid generalizations, what are the specific studies these organizations usually cite in support of population-wide sodium reduction, and what do you think are their flaws?

The rebuttals of health organizations are almost invariably propped up by vague references to an “immense” – usually unspecified – body of research which “proves” the beneficial effects of sodium reduction for the general population. If they do cite specific studies, it’s usually either

- A group of randomized trials in which the baseline blood pressure of participants was actually much higher than the average 71 mmHg of the general population: 80-89 mmHg, 83-89 mmHg, borderline hypertensives and hypertensives, and hypertensives (>90 mmHg). Though these studies are obviously not useful for general population policymaking, they are, nonetheless, used to bolster the population-wide sodium reduction agenda of health organizations.

- A meta-analysis (which, ironically, would have the same hypothetical methodological weaknesses the AHA and CDC supposedly see in ours) that finds increased risk of stroke in individuals consuming more than 4,945 mg/day. The results don’t conflict with our findings (our healthy range is 2,645 – 4,945 mg/day), but also don’t examine negative outcomes for low sodium intake, so are irrelevant to debate around determining an intake range.

- Follow-ups (1, 2) of two older studies, pooling and analyzing their data with cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and all-cause mortality (ACM) as outcomes. These showed no significant difference between the low sodium group (ACM = 2.3%) and the normal sodium group (ACM = 2.6 %) (p = 0.58), thus confirming that sodium reduction may have no effect. The authors did, however, on several occasions, dissect the results by means of multiple adjustments, and did succeed in finding a few marginal or borderline significant results in favor of sodium reduction. The analyses behind these results, though, were not predefined in a protocol and should therefore be considered as having an extremely high risk of bias.

These flawed or irrelevant studies tell us that, concerning the general population, the blood pressure surrogate link between sodium intake and mortality is unreliable. As a matter of fact, the blood pressure surrogate link has been opposed by a meta-analysis that accounted for the full range of global population blood pressure and showed negative side effects for sodium reduction.

Where does this leave us?

As blood pressure is obviously not a reliable link between sodium intake and mortality, the conclusion of the aforementioned 2013 IOM report based on evidence from population studies is the best we have. This report was conducted by independent researchers and sponsored by the CDC, who, for less-than-transparent reasons, chose to follow the example of the AHA by rejecting their own report. As previously mentioned, this report found no evidence to establish whether reducing sodium intake below 2,300 mg/day either decreases or increases CVD risk in the general population. It also found no evidence in support of recommending different sodium intakes to diseased and normal groups, and did find evidence for potential harm in a sodium intake below 1,500 mg. However, the report failed to specify the dimensions of a safe sodium intake zone, but, by implication, indicated that such a safe zone does exist, consistent with the experience of all other essential nutrients.

In your opinion, what should organizations like the CDC and AHA, who control the development and implementation of public health policy, be doing now, in light of this new research?

Any policy like the current one that would aim to have 95% of the world’s population drastically alter their diet ought to be based upon strong, irrefutable scientific evidence.

I think that, instead of immediately moving to accuse dissenting scientists of economic and intellectual corruption, it may be more appropriate for powerful health organizations to ask what scientific mind would buy a theory as simplistic as the one currently governing sodium intake policy (sodium intake leads to high blood pressure, which leads to death) without a modicum of skepticism? Would it be so unreasonable for these groups to at least take our skepticism seriously, instead of reflexively attempting to explain away the results?

Our study provides evidence that a U/J shaped curve exists for the association between sodium intake and health outcome, as it does with all other nutrients. I will be the first to admit that this evidence is based on observational population studies, which are inevitably subject to flaws caused by imprecise measurements and confounders. These flaws, though, are greatly mitigated by the inclusion of a large number of participants, by statistical adjustments, by sensitivity analyses of subgroups, and by consistency in results between several independent studies.

There can never be any scientific guarantee that these safeguards eliminate all flaws; on the other hand, though, in the absence of a conflicting body of data, the IOM report and our analysis should be included in the determination of public policy, not ignored. Any policy like the current one that would aim to have 95% of the world’s population drastically alter their diet ought to be based upon strong, irrefutable scientific evidence.

Niels Graudal, MD, DMsc, is the lead author of “Compared With Usual Sodium Intake, Low- and Excessive-Sodium Diets Are Associated With Increased Mortality: A Meta-Analysis” (available to read for free for a limited time) with Gesche Jürgens, Bo Baslund1 and Michael H. Alderman in the American Journal of Hypertension. He is a chief consultant at the Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark and is mainly treating patients with systemic inflammatory diseases. He has a special interest in meta-analyses

The American Journal of Hypertension is a monthly, peer-reviewed journal that provides a forum for scientific inquiry of the highest standards in the field of hypertension and related cardiovascular disease. The journal publishes high-quality original research and review articles on basic sciences, molecular biology, clinical and experimental hypertension, cardiology, epidemiology, pediatric hypertension, endocrinology, neurophysiology, and nephrology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: heart health fitness concept. © cosmin4000 via iStockphoto.

The post New sodium intake research and the response of health organizations appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlanaP,

on 1/29/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

aids,

conspiracy,

CDC,

HIV,

chandra,

baby boomers,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Science & Medicine,

Health & Medicine,

mistrust,

Gerontologist,

2013 ,

Chandra Ford,

Geronologist,

Gerontology,

HIV testing,

2013 ,

2013 ,

2013 ,

Add a tag

By Chandra Ford

The seventh of February will mark the thirteenth National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. Despite the fact that blacks make up only 14% of the US population, the CDC reports that blacks accounted for 44% of all newly reported HIV infections in 2009, the HIV infection rate among Latinos was nearly three times as high as that of whites, and 1 in 4 persons living with HIV/AIDS in the USA is an older adult (50+ years old).

The CDC reported that 1,600 White, 450 Black, and 300 Latino men aged 50 or older acquired HIV in 2009 through unprotected sex with other men. In other research conducted among senior-housing residents, investigators learned that 42% of residents had been sexually active within the previous six months. One third of the sexually active residents reported two or more partners during that period, but only 20% had regularly used condoms.

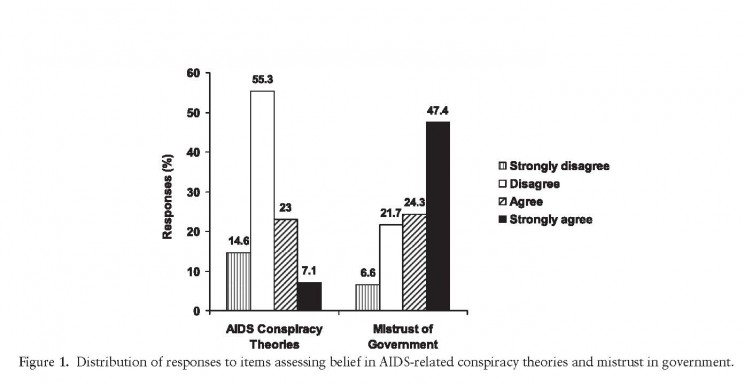

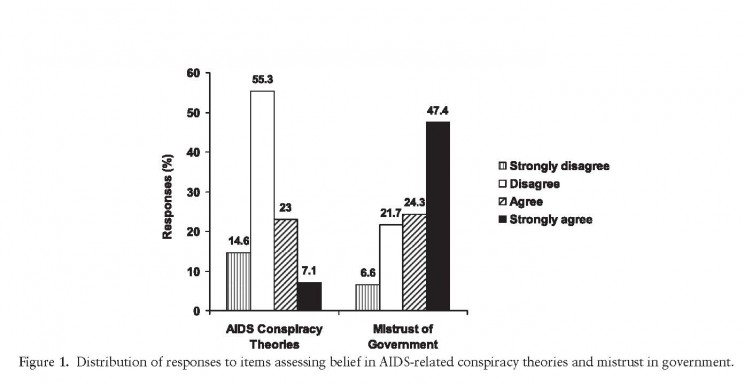

Alarmingly, older adults are prone to be disproportionately diagnosed in the late stages of HIV disease. Many older Americans who seek services in public health venues do not undergo testing for HIV infection, some due to mistrust in the government. Researchers in a recent study found among the 226 participants, 30% reported belief in AIDS conspiracy theories, 72% reported government mistrust, and 45% reported not undergoing HIV testing within the past 12 months.

Among African Americans, endorsements of AIDS conspiracy theories stem from historical experiences with racism and medical discrimination, although knowledge of African Americans’ experiences may lead members of other racial/ethnic groups to endorse such theories.

Making HIV testing routine in public health venues may be an efficient way to improve early diagnosis among at-risk older adults. Alternative possibilities include expanding HIV testing in nonpublic health venues. Finally, identifying particular sources of misinformation and mistrust would appear useful for appropriate targeting of HIV testing strategies in the future.

Key calendar dates:

7 February 2013 National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

19 May 2013 Asian Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

27 June 2013 National HIV Testing Day

15 October 2013 National Latino HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

1 December 2013 World AIDS Day

For further reading:

Dr. Chandra Ford is an assistant professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at UCLA. Her areas of expertise are in the social determinants of HIV/AIDS disparities, the health of sexual minority populations and Critical Race Theory. Ford has received several competitive awards, including the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Services Award (an individual dissertation grant) from the National Institutes of Health and a North Carolina Impact Award for her research contributions to North Carolinians. Her most recent research, “Belief in AIDS-Related Conspiracy Theories and Mistrust in the Government” in The Gerontologist, is available to read for free for a limited time.

The Gerontologist, published since 1961, is a bimonthly journal (first issue in February) of The Gerontological Society of America that provides a multidisciplinary perspective on human aging through the publication of research and analysis in gerontology, including social policy, program development, and service delivery. It reflects and informs the broad community of disciplines and professions involved in understanding the aging process and providing service to older people.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post HIV/AIDS testing: suspicion and mistrust among Baby Boomers appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Anastasia Goodstein,

on 8/6/2010

Blog:

Ypulse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Toyota,

k-swiss,

young adult,

fred,

discovery,

cdc,

Ypulse Essentials,

Scion,

hasbro,

Add a tag

Hasbro, Discovery prepare to launch The Hub (The new kids' cable channel will debut on October 10 targeting 6 to 12 year-olds with a mix of popular syndicated series and originals like a live-action adaptation of "Clue") (Los Angeles Times)

- BTS... Read the rest of this post

Hasbro, Discovery prepare to launch The Hub (The new kids' cable channel will debut on October 10 targeting 6 to 12 year-olds with a mix of popular syndicated series and originals like a live-action adaptation of "Clue") (Los Angeles Times)

- BTS... Read the rest of this post

By: Anastasia Goodstein,

on 9/10/2009

Blog:

Ypulse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Ypulse Research,

cdc,

Youth Marketing,

youth trends,

mediasnackers,

alloy media + marketing,

beloit,

pew rew research,

the way web makes me feel,

Add a tag

Today we bring you another installment of the latest youth research available for sale or download. Remember if your company has comprehensive research for sale that focuses on youth between the ages of 8 and 24, email me to be included in the next... Read the rest of this post

By: Rebecca,

on 5/5/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

swine flu,

WHO,

H1N1,

Gerald Ford,

OIE,

swine flu outbreak of 1976,

Tom Vilsack,

Gerald,

of,

Tom,

Politics,

Current Events,

flu,

A-Featured,

Media,

spanish,

Ford,

CDC,

spanish flu,

swine,

outbreak,

1976,

Vilsack,

Add a tag

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The  Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at “swine flue”. Read his previous OUPblogs here.

Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at “swine flue”. Read his previous OUPblogs here.

“Swine flu” or a strand of influenza A subtype “H1N1?” Try as federal officials might, the media continues to resist their call to term the “swine flu” the new strain of “H1N1″ virus.

At a press conference last Tuesday, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack was at pains to say, “This really isn’t swine [flu], it’s H1N1 virus.” He also explained why: “and it is significant because there are a lot of hard-working families whose livelihood depends on us conveying this message.” (At least ten countries have placed bans on the import of pork even though the World Health Organization has attested that H1N1 is an air-borne and not a food-borne virus.)

The hegemony of “swine flu” over “H1N1″ is even more peculiar given that the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) reports that the particular strand of H1N1 virus (which typically infect pigs) that is causing the current epidemic has not previously been reported in pigs and actually contains avian and human components. It was only on May 2, long after “swine flu” had gained rhetorical currency that the strain was found in pigs at a farm in Alberta, Canada. Even there the story has a twist - the pigs had gotten infected because of their contact with a farm worker who had recently returned from Mexico, and not the other way around - prompting some to suggest that the proper nomenclature ought to be “human flu” or “Mexican flu.”

But the media’s job is to transmit the news in the best way that rolls of one’s tongue, not deal with the fallout of their infelicitous use of words. To be fair, administration officials were slow to catch on. As late as April 26, two days before Vilsack’s press conference, the White House and Richard Besser of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) were still referring to the “swine flu.” Clearly, the pork lobbyists aren’t going to win this battle and the malapropistic epidemic will continue. Administration officials should know that if they really wanted a working alternative to “swine flu,” they would have to do a lot better than a robotic scientific abbreviation.

Our current malapropism has an ancient pedigree. The 1918-1920 H1N1 pandemic called the “Spanish Flu” didn’t start in Spain (and probably started in Kansas). This is ironic, because the “Spanish Flu” acquired its name only because Spain was a neutral country in WW1 and with no state censorship of news of the disease, was offering the most reliable information about it. This ended up generating the impression that the disease originated and was particularly widespread in Spain. Even when the media is not trying, it defines and shapes our reality.

Why does any of this matter? Because words characterize an issue in such a way as to insinuate a cause and to frame our reactions. Sometimes, words can even drive mass hysteria. Consider the “swine flu” outbreak in 1976, which claimed a single life at Fort Dix, NJ. Because this particular strain of virus looked a lot like the one that caused the “Spanish Flu” of 1918-1920 (also misleadingly named), public health officials convinced President Gerald Ford to commence a mass immunization program for all Americans. The use of a sledgehammer to crack a nut was not without consequences. Of the 40 million Americans immunized, about 500 developed Guillain-Barré syndrome, a paralyzing neuromuscular disorder.

So let us pick our words carefully, lest our slovenly words presage our slovenly deeds.

By: Rebecca,

on 7/7/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Medical Mondays,

CDC,

David Michaels,

doubt,

Reye,

tobacco,

aspirin,

Science,

Health,

Add a tag

David Michaels is a scientist and former government regulator. During the Clinton Administration, he served as Assistant Secretary of Energy for Environment, Safety and Health, responsible for protecting the health and safety of the workers, neighboring communities, and the environment surrounding the nation’s nuclear weapons factories. He currently directs the Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy at The George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services. His most recent book, Doubt is Their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health explains how many of the scientists who spun science for tobacco have become practitioners in the lucrative world of product defense. Whatever the story- global warming, toxic chemicals, sugar and obesity, secondhand smoke- these scientists generate studies designed to make dangerous exposures appear harmless. The excerpt below is taken from the introduction to Doubt Is Their Product.

Since 1986 every bottle of aspirin sold in the United States has included a label advising parents that consumption by children with viral illnesses greatly increases their risk of developing Reye’s syndrome, a serious illness that often involves sudden damage to the brain or liver. Before that mandatory warning was required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the toll from this disease was substantial: In one year—1980—555 cases were reported, and many others quite likely occurred but went unreported because the syndrome is easily misdiagnosed. One in three diagnosed children died.

Today, less than a handful of Reye’s syndrome cases are reported each year—a public health triumph, surely, but a bittersweet one because a untold number of children died or were disabled while the aspirin  manufacturers delayed the FDA’s regulation by arguing that the science establishing the aspirin link was incomplete, uncertain, and unclear. The industry raised seventeen specific ‘‘flaws’’ in the studies and insisted that more reliable ones were needed. The medical community knew of the danger, thanks to an alert issued by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), but parents were kept in the dark. Despite a federal advisory committee’s concurrence with the CDC’s conclusions about the link with aspirin, the industry even issued a public service announcement claiming ‘‘We do know that no medication has been proven to cause Reyes’’ (emphasis in the original). This campaign and the dilatory procedures of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget delayed a public education program for two years and mandatory labels for two more. Only litigation by Public Citizen’s Health Research Group forced the recalcitrant Reagan Administration to act. Thousands of lives have now been saved—but only after hundreds had been lost.

manufacturers delayed the FDA’s regulation by arguing that the science establishing the aspirin link was incomplete, uncertain, and unclear. The industry raised seventeen specific ‘‘flaws’’ in the studies and insisted that more reliable ones were needed. The medical community knew of the danger, thanks to an alert issued by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), but parents were kept in the dark. Despite a federal advisory committee’s concurrence with the CDC’s conclusions about the link with aspirin, the industry even issued a public service announcement claiming ‘‘We do know that no medication has been proven to cause Reyes’’ (emphasis in the original). This campaign and the dilatory procedures of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget delayed a public education program for two years and mandatory labels for two more. Only litigation by Public Citizen’s Health Research Group forced the recalcitrant Reagan Administration to act. Thousands of lives have now been saved—but only after hundreds had been lost.

Of course, the aspirin manufacturers did not invent the strategy of preventing or postponing the regulation of hazardous products by questioning the science that reveals the hazards in the first place. I call this strategy ‘‘manufacturing uncertainty’’; individual companies—and entire industries—have been practicing it for decades. Without a doubt, Big Tobacco has manufactured more uncertainty over a longer period and more effectively than any other industry. The title of this book comes from a phrase unwisely committed to paper by a cigarette executive: ‘‘Doubt is our product since it is the best means of competing with the ‘body of fact’ that exists in the minds of the general public. It is also the means of establishing a controversy’’ (emphasis added).

There you have it: the proverbial smoking gun. Big Tobacco, left now without a stitch of credibility or public esteem, has finally abandoned its strategy, but it showed the way. The practices it perfected are alive and well and ubiquitous today. We see this growing trend that disingenuously demands proof over precaution in the realm of public health. In field after field, year after year, conclusions that might support regulation are always disputed. Animal data are deemed not relevant, human data not representative, and exposure data not reliable. Whatever the story—global warming, sugar and obesity, secondhand smoke—scientists in what I call the ‘‘product defense industry’’ prepare for the release of unfavorable studies even before the studies are published. Public relations experts feed these for-hire scientists contrarian sound bites that play well with reporters, who are mired in the trap of believing there must be two sides to every story. Maybe there are two sides—and maybe one has been bought and paid for.

* * *

As it happens, I have had the opportunity to witness what is going on at close range. In the Clinton administration, I served as Assistant Secretary for Environment, Safety, and Health in the Department of Energy (DOE), the chief safety officer for the nation’s nuclear weapons facilities. I ran the process through which we issued a strong new rule to prevent chronic beryllium disease, a debilitating and sometimes fatal lung disease prevalent among nuclear weapons workers. The industry’s hired guns acknowledged that the current exposure standard for beryllium is not protective for employees. Nevertheless, they claimed, it should not be lowered by any amount until we know with certainty what the exact final number should be.

As a worker, how would you like to be on the receiving end of this logic?

Christie Todd Whitman, the first head of the Environmental Protection Agency under the second President Bush, once said, ‘‘The absence of certainty is not an excuse to do nothing.’’ But it is. Quite simply, the regulatory agencies in Washington, D.C., are intimidated and outgunned— and quiescent. While it is true that industry’s uncertainty campaigns exert their influence regardless of the party in power in the nation’s capital, I believe it is fair to say that, in the administration of President George W. Bush, corporate interests successfully infiltrated the federal government from top to bottom and shaped government science policies to their desires as never before. In October 2002 I was the first author of an editorial in Science that alerted the scientific community to the replacement of national experts in pediatric lead poisoning with lead industry consultants on the Pertinent advisory committee. Other such attempts to stack advisory panels with individuals chosen for their commitment to a cause—rather than for their expertise—abound.

Industry has learned that debating the science is much easier and more effective than debating the policy. Take global warming, for example. The vast majority of climate scientists believe there is adequate evidence of global warming to justify immediate intervention to reduce the human contribution. They understand that waiting for absolute certainty is far riskier—and potentially far more expensive—than acting responsibly now to control the causes of climate change. Opponents of action, led by the fossil fuels industry, delayed this policy debate by challenging the science with a classic uncertainty campaign. I need cite only a cynical memo that Republican political consultant Frank Luntz delivered to his clients in early 2003. In ‘‘Winning the Global Warming Debate,’’ Luntz wrote the following: ‘‘Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate. . . . The scientific debate is closing [against us] but not yet closed. There is still a window of opportunity to challenge the science’’ (emphasis in original).

Sound familiar? In reality, there is a great deal of consensus among climate scientists about climate change, but Luntz understood that his clients can oppose (and delay) regulation without being branded as antienvironmental by simply manufacturing uncertainty.

ShareThis