new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: American Television Music, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 3 of 3

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: American Television Music in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 2/21/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

black history month,

Jazz,

broadway,

NBC,

cole,

CBS,

Nat King Cole,

*Featured,

sponsorship,

Tuning In,

Arts & Leisure,

Tin Pan Alley,

American Television Music,

Ron Rodman,

African American musicians,

Dr. Billy Taylor,

Flip Wilson,

jazz pianist,

King Cole Trio,

Leslie Uggams,

mixed race performance,

musical variety show,

Nathanial Adams Coles,

race barrier,

Music,

Add a tag

By Ron Rodman

In this blog last month, I wrote about Dr. Billy Taylor and his pioneering work on television as an advocate for jazz. To celebrate Black History Month, it is appropriate to mention another African American musician who was a pioneer on American television: Nat King Cole, jazz pianist and vocalist, was the first African American musician to host a nationally-broadcast musical variety show in the history of television.

Publicity photo from the premiere of The Nat King Cole Show.

Nathanial Adams Coles was born in 1919 in Montgomery, Alabama. He first learned to play piano around the age of four with help from his mother, a church choir director, and by his early teens, was studying classical piano. He was drawn to the music of jazz pianist

Earl “Fatha” Hines, and eventually abandoned classical for jazz, which became his lifelong passion. At 15, he dropped out of school to become a jazz pianist full-time, and developed an act with his brother Eddie for a time, which led to his first professional recordings in 1936. He later joined a national tour for the musical revue

Shuffle Along, performing as a pianist.

In 1937, Cole started to put together what would become the “King Cole Trio,” the name being a play on the children’s nursery rhyme. As part of the trio, Cole expanded his own role in the group, both playing jazz piano and singing with his rich, velvety baritone voice. The trio toured extensively and finally landed on the charts in 1943 with Cole’s song, “That Ain’t Right.” His first big hit the following year was “Straighten Up and Fly Right,” a song reportedly inspired by one of his father’s sermons. The trio continued its rise to the top with such pop hits as the holiday classic “The Christmas Song” and the ballad “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons.”

By the 1950s, Nat King Cole emerged as a popular solo performer. He scored numerous hits, with such songs as “Nature Boy,” “Mona Lisa,” “Too Young, ” and “Unforgettable.” He worked with many of the greatest jazz artists in the country, like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, arranger Nelson Riddle, and others.

However, the 1950s was a difficult decade for African American entertainers. In his performances around the country, Cole had encountered racism firsthand, especially while touring in the South. He had been attacked by white supremacists during a mixed race performance in Alabama. Yet, he was also criticized by other African Americans for his less-than-supportive comments about racial integration, and for performances for segregated audiences. Cole considered himself an entertainer and not an activist, and often sought to assimilate with white audiences.

1956 proved to be a pivotal year for Nat King Cole, and he was to become not just an entertainer, but also a pioneer for equal rights. By the mid-1950s, he had achieved status as a mainstream performer and sought to pursue this career as other stars had done — to produce and star in his own television show. His bid for a TV show brought with it a sense of mission. “It could be a turning point,” he realized, “so that Negroes may be featured regularly on television.” Cole realized the stakes were high, and said, “If I try to make a big thing out of being the first and stir up a lot of talk, it might work adversely.” Cole and his agents negotiated with CBS for a show, but his own program never materialized. Cole’s manager then tried NBC, and they successfully reached an agreement for The Nat “King” Cole Show.

The Nat “King” Cole Show debuted on 5 November 1956. The show aired without a sponsor, but NBC agreed to pay for initial production costs; the network assumed that once the show actually aired and advertisers were able to see its sophistication, a national sponsor would emerge. Cole exuded his benign, soft-spoken persona on the set, chatting with the TV audience and singing Broadway and Tin Pan Alley tunes. But the show was innovative in that it also featured Cole in his original role as a jazz pianist, playing and singing with jazz notables such as Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald. Cole also used his connections to bring other high caliber musicians to the show, many of whom voluntarily appeared with minimal compensation. Some of these included Harry Belafonte, Mel Tormé, Frankie Laine, and Peggy Lee (shown below).

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Despite the high musical quality of the show, the race barrier seemed too much for the predominantly white TV audience of the 1950s to overcome. Many national companies balked at sponsorship, as they did not want to upset their white customers in the South who did not want to see a black man on TV shown in anything other than a subservient position. Although NBC agreed to fund the show until a sponsor could be found, Cole decided to cancel the show himself in its second season, disappointed with ratings and lack of sponsorship. Cole was quoted as saying of the doomed series, “Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark.” The last show was aired on 17 December 1957. After he cancelled his show, Nat King Cole continued to appear on other TV shows like The Ed Sullivan Show, The Garry Moore Show, and others.

Though short lived, The Nat “King” Cole Show paved the way for other black entertainers to find their way to television in the next decade. 1967 witnessed the premier of The Sammy Davis, Jr. Show on NBC, as a mid-season replacement that ran for 15 episodes.

Click here to view the embedded video.

In 1969, singer Leslie Uggams, hosted The Leslie Uggams Show, a musical comedy variety series that aired on CBS for one season in 1969.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Unfortunately, American audiences still seemed uncomfortable with TV shows hosted by sophisticated black musicians, and it finally took a comedian — Flip Wilson — to host a successful show, The Flip Wilson Show, which ran for four seasons on NBC from 1970-1974.

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Publicity photo from the premiere of The Nat King Cole Show. NBC Television. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Nat “King” Cole Show: pioneer of music television appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/29/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dave Brubeck,

brubeck,

American Television Music,

Ron Rodman,

Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor,

Teresa Reed,

The Subject is Jazz,

seldes,

Music,

television,

Jazz,

teresa,

Billy Taylor,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Tuning In,

Arts & Leisure,

Add a tag

By Ron Rodman

The New Year is a time of looking forward to the future and back to the past. Looking back, last year witnessed the death of Dave Brubeck, one of the all time great jazz musicians. Brubeck became famous through his live performances and his recordings, especially the seminal Time Out album released in 1958. But he also became famous through his many appearances on American and international television, beginning with The Colgate Comedy Hour in 1955, and appearing on variety shows such as The Steve Allen Plymouth Show (1958), The Timex All-Star Jazz Show (1957), and The Ed Sullivan Show (1955, 1960, 1962). As his fame grew, Brubeck also became the subject of several TV documentaries, including prestigious programs like The Twentieth Century (1961) and The Bell Telephone Hour (1968). He was also an honored guest in the few exclusively jazz programs that aired in the 1960s. He appeared on Jazz 625 in 1964 and made several appearances on Jazz Casual, an occasional series that ran on the National Educational Network from 1961-68.

Here’s the Brubeck Quartet performing for a broadcast of Jazz Casual in 1961.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Brubeck made many more TV appearances throughout the world in the 1960s and 1970s, many of which can be seen on YouTube.

As important as Brubeck’s TV appearances were, perhaps no one furthered the cause of jazz on television more than Billy Taylor, who also died recently in 2010. After graduating college in 1942, Taylor got his professional start with Ben Webster’s Quartet on New York’s famed 52nd Street. He then served as the house pianist at the legendary club Birdland, where he performed with such celebrated masters as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis. He went on to receive a masters and doctor’s degree in music education at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and served as Duke Ellington Fellow at Yale. He divided his career as performer, writer, jazz advocate, and educator for the remainder of his life.

Taylor’s contributions to television music were manifold. He was the music director and band leader for The David Frost Show from 1969-72, becoming the first African American musician to hold that position on a TV talk show. He served as “Jazz and Modern Music Correspondent” for CBS News Sunday Morning from 1981-2002. He also was a contributor to many jazz documentaries, notably for Louis Armstrong (1971) and Duke Ellington (1981, 2000).

Taylor made his TV debut on the Steve Allen’s Tonight! show in 1956. Next, he appeared on Jazz Party in 1958. That year proved pivotal, as Taylor was asked to be music director for a new TV series, The Subject is Jazz, produced by NBC.

Before his death, Dr. Taylor was interviewed for an upcoming book of his memoirs written by Teresa Reed, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor (Indiana University Press). Taylor had this to say about the program:

“A second opportunity in 1958 came by way of Marshall Stearns. By that time, his deep interest in jazz had turned to television, and in collaboration with Leonard Feather, he came up with the idea to do a series of thirteen shows as part of a program called The Subject is Jazz. Although jazz had been on radio for decades, The Subject is Jazz would be the very first program of its type to come to television. Stearns and Feather were both writers, however, and neither knew a thing about the practical aspects of musical direction or doing a television show. So it was for this purpose that they hired me. Having experienced rejection from MENC, it was crucial to me that The Subject is Jazz develop into a high-quality, educational show. The Subject is Jazz was distributed through NBC network facilities to educational TV stations. Although a variety of different musicians performed on the show, my basic combo included Osie Johnson on drums, Eddie Safranski on bass, Mundell Lowe on guitar, Tony Scott on clarinet, Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, and Carl (later known as “Doc”) Severinsen on trumpet.

“The show featured some great music and stimulating conversations with people like Duke Ellington, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, all of whom were serious connoisseurs of jazz. But a major flaw was the show’s dry, stoic, and overly academic presentation. There were lots of people who knew and loved the music, people who would have made excellent commentators for the show… Rather than get some known radio personality, the producer hired Gilbert Seldes, a Harvard-trained cultural critic who read to the television audience from his stack of handheld notes. I knew that the audience for The Subject is Jazz was vastly different from the audience I typically encountered while I was performing in clubs. Gilbert Seldes was a conservative, grandfatherly type in his mid-sixties who sported a professorial bowtie and spoke in a sort of scholarly monotone, using carefully measured language as one does while delivering a lecture. He was an intellectual speaking to a Saturday-afternoon television audience of intellectuals who wanted to understand the music with their minds as much as they enjoyed it with their ears and hearts. Working in this context, it was my job to combine clear, articulate answers to Seldes’s questions with musical demonstrations of whatever I was explaining.

“By today’s more sophisticated, high-tech standards, The Subject is Jazz may seem like a very primitive and ‘square’ attempt at using mass media to educate the public about the music. Yet, in some ways, the show was quite ahead of its time. During the thirteen-week run of The Subject is Jazz I also had an opportunity to perform some of my own compositions… The last episode featured a composition that was my tribute to Charlie Parker, titled “Early Bird.”” (Teresa Reed, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor, p.137-38)

Here is a video of that last episode:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television. His thanks to Dr. Teresa Reed, Professor of Music at the University of Tulsa, for this “sneak peek” at her upcoming book, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor. Look for it on bookshelves soon!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Subject is Jazz appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/25/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

holidays,

Sports,

Super Bowl,

NFL,

National Football League,

american football,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Tuning In,

Arts & Leisure,

American Television Music,

pregame shows,

professional football,

Ron Rodman,

pregame,

Add a tag

By Ron Rodman

Sports fans eagerly anticipate television broadcasts of their favorite sports, whether it is baseball, basketball, soccer, hockey, boxing, golf, auto racing, or any of the other events aired on the tube. In the USA, the biggest television sports event is undoubtedly (American) professional football: the National Football League. In 2011, NBC’s “Sunday Night Football” was the highest-rated program on American TV; nine of the ten most-watched shows that year were NFL games or pregame shows (the other was the Academy Awards), and each of the 21 biggest audiences in TV history are Super Bowls. Football’s popularity may be attributed to the coincidence of the NFL season with the American holiday season (i.e., Thanksgiving, Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanza, New Year’s Day, etc.). For many sports fans, football on TV is synonymous with the holidays, and vice versa. One might say that football is part of American holiday festivities.

Professional football was broadcast on television as far back as 1939, when the Philadelphia Eagles played the Brooklyn Dodgers on October 22nd. Games were not telecast with any regularity until the 1950s, but after the 1958 NFL Championship Game between the Baltimore Colts and the New York Giants — the so-called “Greatest Game Ever Played” — football on television gained an enthusiastic following. The DuMont Network and ABC broadcast games in these early years, but NBC and CBS soon bought the rights to broadcast all professional football, with CBS broadcasting the NFL games, and NBC broadcasting AFL games.

By the early 1970s, NFL football became so popular that telecasts featured “pregame shows” that had high quality sets, analytical commentators (many of whom were former players or coaches) and, of course, catchy musical themes — all done to add an air of festivity to the broadcasts of the games. CBS offered one of the first pregame shows dating back to 1961, eventually becoming “The NFL Today,” in the 1970’s. The program was introduced by an upbeat, “light rock” musical theme, with a sort of light rock motif.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The theme was updated in 1982, adding a disco-style “wah-wah” guitar, and omitting the trombone glissando.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The arrangement was tweaked again in 1983, with the alteration of computer-generated visual images.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Not to be outdone, NBC had their own pregame show, “The NFL on NBC.” NBC became the sole broadcaster for AFL football games in 1964, and when the league merged with the NFL in 1970, NBC retained rights to the AFC games, with CBS taking the NFC. (ABC began airing “Monday Night Football” in 1977.)

The musical theme of “The NFL on NBC” in 1973 featured a driving brass section with “wah-wah” guitar, and a jazz-like sax solo:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Unlike CBS, NBC changed its musical themes frequently. Here’s composer by John Colby’s 1992 theme to the show:

Click here to view the embedded video.

And the 1995-97 version by Randy Edelman:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Like the CBS theme, the latter two NBC themes are festive, almost joyful, reflecting the playful nature of sports telecasts.

The Fox Network entered the NFL TV market in 1994 when the network outbid CBS for NFC games. The theme for its show, “Fox NFL Sunday,” was composed by Scott Schreer, Reed Hays, and Phil Garrod, who pitched three separate songs to Fox, who then spliced them together into one.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The use of the minor key and heavy percussion of the Fox theme creates a more serious tone than the more laid-back light jazz/rock themes of its predecessor. The theme leads to a perception that the broadcast is less about a festive game of skilled athletes, and more about a life-or-death combat by gladiators.

Fox’s gladiatorial theme was soon imitated by both NBC and CBS, who in turn used minor key, martial music for their own broadcasts. In my September blog post, I wrote about John Williams’ theme to NBC’s “Sunday Night Football,” called by at least one fan as “Football’s Imperial March.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

What caused the shift from festive athletes to combative gladiators in American pro football TV broadcasts? It may have much to do with America’s militaristic posture during the past decade (two wars fought), or television networks’ desire to align the game with the combative, hyper-masculine ethos that emerged from the post 9/11 era.

However, I would contend that we haven’t lost the festive spirit completely in pro football on TV. While the “Fox NFL Sunday” theme has become nearly synonymous with the NFL with its serious, militaristic tone, if we listen to the opening motif of the theme, we might detect a resemblance to a portion of a famous winter holiday song:

Click here to view the embedded video.

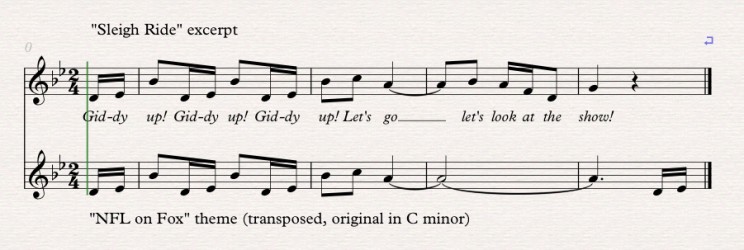

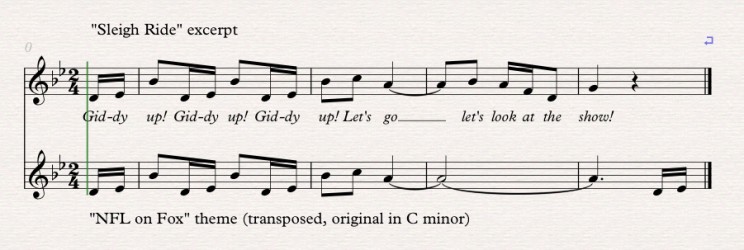

The song is Leroy Anderson’s famous “Sleigh Ride,” sung here in a classic recording by Johnny Mathis. The melody at the beginning of the “B” section (“Giddy up! Giddy up! Giddy up! Let’s go!”) has a melodic profile identical to the beginning of the Fox football theme. Here is a melodic comparison:

So, did Schreer, Hays, and Garrod get their inspiration from a festive holiday song? Maybe televised football hasn’t lost its festive spirit after all!

Happy Holidays, everyone!

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of Ron Rodman. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Football, festivity, and music appeared first on OUPblog.