By James Secord

We tend to think of ‘science’ and ‘literature’ in radically different ways. The distinction isn’t just about genre – since ancient times writing has had a variety of aims and styles, expressed in different generic forms: epics, textbooks, lyrics, recipes, epigraphs, and so forth. It’s the sharp binary divide that’s striking and relatively new. An article in Nature and a great novel are taken to belong to different worlds of prose. In science, the writing is assumed to be clear and concise, with the author speaking directly to the reader about discoveries in nature. In literature, the discoveries might be said to inhere in the use of language itself. Narrative sophistication and rhetorical subtlety are prized.

This contrast between scientific and literary prose has its roots in the nineteenth century. In 1822 the essayist Thomas De Quincey broached a distinction between the ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power.’ As De Quincey later explained, ‘the function of the first is to teach; the function of the second is to move.’ The literature of knowledge, he wrote, is left behind by advances in understanding, so that even Isaac Newton’s Principia has no more lasting literary qualities than a cookbook. The literature of power, on the other hand, lasts forever and draws out the deepest feelings that make us human.

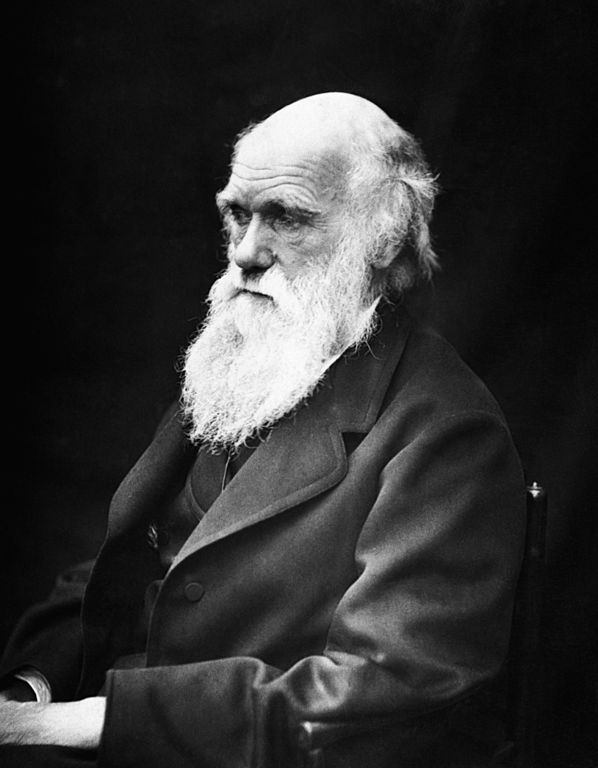

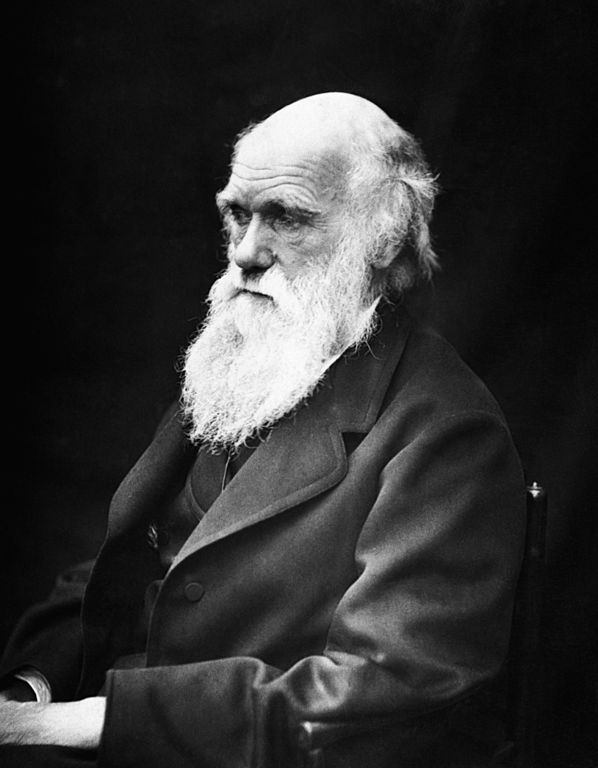

The effect of this division (which does justice neither to cookbooks nor the Principia) is pervasive. Although the literary canon has been widely challenged, the university and school curriculum remains overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of key authors and texts. Only the most naive student assumes that the author of a novel speaks directly through the narrator; but that is routinely taken for granted when scientific works are being discussed. The one nineteenth-century science book that is regularly accorded a close reading is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). A number of distinguished critics have followed Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots in attending to the narrative structures and rhetorical strategies of other non-fiction works – but surprisingly few.

It is easy to forget that De Quincey was arguing a case, not stating the obvious. A contrast between ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power’ was not commonly accepted when he wrote; in the era of revolution and reform, knowledge was power. The early nineteenth century witnessed remarkable experiments in literary form in all fields. Among the most distinguished (and rhetorically sophisticated) was a series of reflective works on the sciences, from the chemist Humphry Davy’s visionary Consolations in Travel (1830) to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33). They were satirised to great effect in Thomas Carlyle’s bizarre scientific philosophy of clothes, Sartor Resartus (1833-34).

These works imagined new worlds of knowledge, helping readers to come to terms with unprecedented economic, social, and cultural change. They are anything but straightforward expositions or outdated ‘popularisations’, and deserve to be widely read in our own era of transformation. Like the best science books today, they are works in the literature of power.

James Secord is Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project, and a fellow of Christ’s College. His research and teaching is on the history of science from the late eighteenth century to the present. He is the author of the recently published Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post When science stopped being literature appeared first on OUPblog.

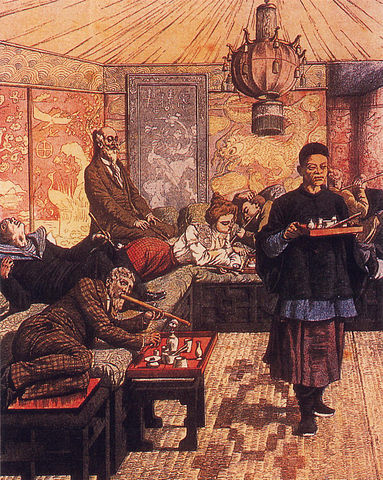

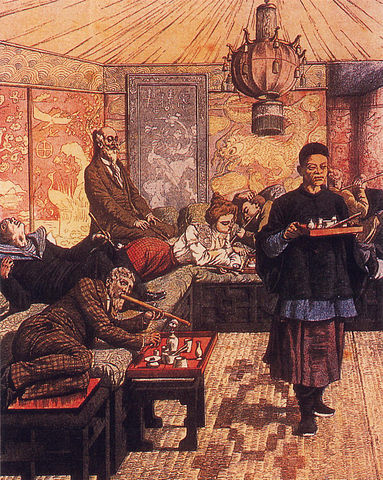

By Robert Morrison

In The Metaphysics of Morals (1797), Immanuel Kant gives the standard eighteenth-century line on opium. Its “dreamy euphoria,” he declares, makes one “taciturn, withdrawn, and uncommunicative,” and it is “therefore… permitted only as a medicine.” Eighty-five years later, in The Gay Science (1882), Friedrich Nietzsche too discusses drugs, but he has a very different story to tell. “Who will ever relate the whole history of narcotica?” he asks pointedly. “It is almost the history of ‘culture’, of so-called high culture.” What caused this seismic shift in attitude? How did opium, in less than a century, pass from a drug understood primarily as a medicine to a drug used and abused recreationally, not just in “high culture”, but across the social strata?

The short answer is Thomas De Quincey. In his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in the London Magazine for September and October 1821, he transformed our perception of drugs. De Quincey invented recreational drug-taking, not because he was the first to swallow opiates for non-medical reasons (he was hardly that), but because he was the first to commemorate his drug experience in a compelling narrative that was consciously aimed at — and consumed by — a broad commercial audience. Further, in knitting together intellectualism, unconventionality, drugs, and the city, De Quincey mapped in the counter-cultural figure of the bohemian. He was also the first flâneur, high and anonymous, graceful and detached, strolling through crowded urban sprawls trying to decipher the spectacles, faces, and memories that reside there. Most strikingly, as the self-proclaimed “Pope” of “the true church on the subject of opium,” he initiated the tradition of the literature of intoxication with his portrait of the addict as a young man. De Quincey is the first modern artist, at once prophet and exile, riven by a drug that both inspired and eviscerated him.

The short answer is Thomas De Quincey. In his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in the London Magazine for September and October 1821, he transformed our perception of drugs. De Quincey invented recreational drug-taking, not because he was the first to swallow opiates for non-medical reasons (he was hardly that), but because he was the first to commemorate his drug experience in a compelling narrative that was consciously aimed at — and consumed by — a broad commercial audience. Further, in knitting together intellectualism, unconventionality, drugs, and the city, De Quincey mapped in the counter-cultural figure of the bohemian. He was also the first flâneur, high and anonymous, graceful and detached, strolling through crowded urban sprawls trying to decipher the spectacles, faces, and memories that reside there. Most strikingly, as the self-proclaimed “Pope” of “the true church on the subject of opium,” he initiated the tradition of the literature of intoxication with his portrait of the addict as a young man. De Quincey is the first modern artist, at once prophet and exile, riven by a drug that both inspired and eviscerated him.

The Confessions warned some early readers off opium, as De Quincey claimed he intended. “Better, a thousand times better, die than have anything to do with such a Devil’s own drug!” Thomas Carlyle commented after reading the work, while De Quincey’s erstwhile friend and fellow opium addict Samuel Taylor Coleridge insisted that he read the Confessions with “unutterable sorrow…The writer with morbid vanity, makes a boast of what was my misfortune.” But for many other readers, De Quincey’s account of opium was an invitation to experimentation — his drugged highs almost irresistible, and the gothic gloom of his lows even more so. Within months of publication, John Wilson, De Quincey’s closest friend and the lead writer for the powerful Blackwood’s Magazine, heard alarming reports of people recklessly attempting to emulate De Quincey’s drug experiences. “Pray, is it true…that your Confessions have caused about fifty unintentional suicides?” he inquires in a flamboyant Blackwood’s sketch. “I should think not,” the Opium Eater replies indignantly. “I have read of six only; and they rested on no solid foundation.”

Others, however, did not find the situation funny. One doctor recorded a sharp increase in the number of people overdosing on opium “in consequence of a little book that has been published by a man of literature.” The authors of The Family Oracle of Health (1824) were even angrier. “The use of opium has been recently much increased by a wild, absurd, and romancing production, called the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater,” they declared. “We observe, that at some late inquests this wicked book has been severely censured, as the source of misery and torment, and even of suicide itself, to those who have been seduced to take opium by its lying stories about celestial dreams, and similar nonsense.”

Others, however, did not find the situation funny. One doctor recorded a sharp increase in the number of people overdosing on opium “in consequence of a little book that has been published by a man of literature.” The authors of The Family Oracle of Health (1824) were even angrier. “The use of opium has been recently much increased by a wild, absurd, and romancing production, called the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater,” they declared. “We observe, that at some late inquests this wicked book has been severely censured, as the source of misery and torment, and even of suicide itself, to those who have been seduced to take opium by its lying stories about celestial dreams, and similar nonsense.”

De Quincey was characteristically divided on the influence of his Confessions. In the work itself he states that his primary objective is to reveal the powers of the drug: opium is “the true hero of the tale,” and “the legitimate centre on which the interest revolves.” Yet in Suspiria de Profundis (1845), the sequel to the Confessions, he maintains that its “true hero” is, not opium, but the powers of his imaginative — and especially of his dreaming — mind. Elsewhere, De Quincey denied the charges that his writings had encouraged drug abuse: “Teach opium-eating! – Did I teach wine drinking? Did I reveal the mystery of sleeping? Did I inaugurate the infirmity of laughter? . . . My faith is – that no man is likely to adopt opium or to lay it aside in consequence of anything he may read in a book.” In still other instances De Quincey regarded his drug habit as a source of amusement. “Since leaving off opium,” he noted wryly, “I take a great deal too much of it for my health.” More commonly, though, he was horrified by the damage it was inflicting. “It is as if ivory carvings and elaborate fretwork and fair enamelling should be found with worms and ashes amongst coffins and the wrecks of some forgotten life,” he wrote in the midst of one of his many attempts to abjure the drug.

De Quincey’s account of his opiated experiences has left on indelible print on the literature of addiction, and modern commentators continue to grapple with his legacy, though there is no agreement on whether he should be blamed, or absolved, or lauded. In Romancing Opiates (2006), Theodore Dalrymple lambasts him. “In modern society the main cause of drug addiction…is a literary tradition of romantic claptrap, started by Coleridge and De Quincey, and continued without serious interruption ever since,” he asserts. “This claptrap is the main source of popular and medical misconceptions on the subject.” Will Self, however, argues vigorously against such a view. “The truth is that books like…De Quincey’s Confessions no more create drug addicts than video nasties engender prepubescent murderers,” he declares in Junk Mail (1995). “Rather, culture, in this wider sense, is a hall of mirrors in which cause and effect endlessly reciprocate one another in a diminuendo that tends ineluctably towards the trivial.”

Ann Marlowe takes yet another position on the “brilliant, unsurpassed Confessions.” “Ever since I read De Quincey in my early teens,” she writes in How to Stop Time (1999), “I’d planned to try opium,” a far more direct account of “cause and effect” than Self’s halls of opium smoke and mirrors. Yet Marlowe and Self agree that they were both drawn to the drug because of its close association with intellectualism and insight, for both “hoped to pass through the portals of dope” into the “honoured company” of Coleridge and De Quincey. Such reasoning, Marlowe recognizes later, is “the sorriest cliche,” or what Dalrymple would call “claptrap”. But these accounts make plain that De Quincey’s potent memorialization of his drug experience has proven at least as seductive as the drug itself. His Confessions loosed the recreational genies from the medicine bottle and made opiates for the masses. De Quincey was lucky. The drug battered him, but it never finally defeated his creativity or his resolve. Many have not been that fortunate. Diagnosed at aged twenty with an opiate addiction, Self was “appalled to discover that I was not a famous underground writer. Indeed, far from being a writer at all, I was simply underground.”

Robert Morrison is Queen’s National Scholar at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, where he maintains the Thomas De Quincey homepage. For Oxford World’s Classics, he has edited (with Chris Baldick) The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, as well as Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings, and three essays On Murder. Morrison is the author of The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey, which was a finalist for the James Black Memorial Prize. His annotated edition of Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published by Harvard University Press. For Palgrave, he edited (with Daniel Sanjiv Roberts) a collection of essays entitled Romanticism and Blackwood’s Magazine: ‘An Unprecedented Phenomenon’. Read his previous blog posts: “De Quincey’s fine art” and “Vampyre Rising.”

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles articles on the OUPblog via email RSS

Image Credits: (1) Thomas de Quincey – Project Gutenberg eText 19222 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “A New Vice: Opium Dens in France”, cover of Le Petit Journal, 5 July 1903. via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Cropped screenshot from the film trailer Confessions of an Opium Eater (1962) via Wikimedia Commons

The post De Quincey’s wicked book appeared first on OUPblog.

By Robert Morrison

Two hundred and one years ago this month, along the Ratcliffe Highway in the East End of London, seven people from two separate households were brutally murdered. News of the atrocities quickly spread throughout the country, generating levels of terror and moral hysteria that were not seen again until three-quarters of a century later when Jack the Ripper launched his savage career in a neighbouring East End district. Britain had no professional police force until 1829, and so the task of apprehending the killer (or killers) fell to an ill-coordinated group of magistrates, watchmen, and churchwardens who were woefully unprepared for the pressures of a major murder investigation, and who struggled to reassure a terrified populace that justice would be served. “We in the country here are thinking and talking of nothing but the dreadful murders,” wrote Robert Southey in December 1811, safe in his Keswick home three hundred miles from London, but still badly unnerved. “I…never had so mingled a feeling of horror, and indignation, and astonishment, with a sense of insecurity too.”

The killing began near midnight on Saturday, 7 December 1811, when an assassin passed quietly through the unlocked front door of Timothy Marr’s lace and pelisse shop. Once inside he bolted the door behind him and then ruthlessly dispatched all four inhabitants. When the alarm was raised and the door unlocked, eye-witnesses saw Marr’s wife Celia sprawled lifelessly. Marr himself was dead behind the store counter. His apprentice James Gowen was stretched out in the back near a door that led to a staircase. Downstairs in the kitchen, three-month-old Timothy Marr junior was found battered and dead. All four victims had their throats slashed. Twelve days later — again around midnight, again in the same East London area — it all happened a second time, on this occasion in the household of John Williamson, a publican. Williamson himself was found dead in the cellar. He had apparently been thrown down the stairs. His throat was cut. His wife Elizabeth and maid Anna Bridget Harrington were discovered on the main floor, their skulls bludgeoned and their throats slit.

Authorities quickly rounded up and interviewed dozens of people. One of them, John Williams, an Irish seaman in his late twenties, was questioned before the Shadwell magistrates on Christmas Eve, and then sent to Coldbath Fields prison to await further investigation. Suspicion grew as circumstantial evidence mounted against Williams, but before the magistrates could re-examine him, he hanged himself in his prison cell. The circumstances of his death were widely interpreted as a confession of guilt — much to the relief of some of the magistrates — and on New Year’s Eve Williams’s body was publicly exhibited in a procession through the Ratcliffe Highway before being driven to the nearest cross-roads, where it was forced into a narrow hole and a stake driven through the heart. Several officials, however, immediately raised doubts about Williams’s guilt, and in The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders (1971), P. D. James and T. A. Critchley conclude that Williams could not have acted alone, if he was involved at all, and that he may even have been murdered in his prison cell by those who were responsible, an eighth and final victim in the appalling tragedy.

Authorities quickly rounded up and interviewed dozens of people. One of them, John Williams, an Irish seaman in his late twenties, was questioned before the Shadwell magistrates on Christmas Eve, and then sent to Coldbath Fields prison to await further investigation. Suspicion grew as circumstantial evidence mounted against Williams, but before the magistrates could re-examine him, he hanged himself in his prison cell. The circumstances of his death were widely interpreted as a confession of guilt — much to the relief of some of the magistrates — and on New Year’s Eve Williams’s body was publicly exhibited in a procession through the Ratcliffe Highway before being driven to the nearest cross-roads, where it was forced into a narrow hole and a stake driven through the heart. Several officials, however, immediately raised doubts about Williams’s guilt, and in The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders (1971), P. D. James and T. A. Critchley conclude that Williams could not have acted alone, if he was involved at all, and that he may even have been murdered in his prison cell by those who were responsible, an eighth and final victim in the appalling tragedy.

To Thomas De Quincey, the finer points of the investigation mattered little. What impressed him was the audacity, brutality, and inexplicability of the crimes, and in his writings he returns over and over again to the Ratcliffe Highway, always attributing the murders solely to Williams, and exalting, ignoring, or altering details in order to exploit his deep and diverse response to the crimes. In his finest piece of literary criticism, “On the Knocking at the Gate in Macbeth” (1823), De Quincey introduces the satiric aesthetic that enables him to see Williams’s performance “on the stage of Ratcliffe Highway” as “making the connoisseur in murder very fastidious in his taste, and dissatisfied with any thing that has been since done in that line.” Yet De Quincey also peers uneasily into the mind of the killer in order to reflect on the psychology of violence. In Macbeth, he asserts, Shakespeare throws “the interest on the murderer,” where “there must be raging some great storm of passion — jealousy, ambition, vengeance, hatred — which will create a hell within him; and into this hell we are to look.”

Williams is also at the heart of De Quincey’s three essays “On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts.” In the first, published in 1827, De Quincey grazes the brink between horror and comedy as he argues with energetically ironic aplomb that “everything in this world has two handles. Murder, for instance, may be laid hold of by its moral handle… and that, I confess, is its weak side; or it may also be treated aesthetically…that is, in relation to good taste.” Twelve years later, in the second essay, he employs the same satiric topsy-turviness, but in this instance he inverts morality rather than suspending it. “For if once a man indulges himself in murder,” he observes coolly, “very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination.” Finally, in the 1854 “Postscript,” De Quincey changes direction, returning fitfully to the black humour of the first two essays, but concentrating instead on impassioned representations of vulnerability and panic, and in particular on the horror of an unknown assailant descending on an urban household which is surrounded by unsuspecting neighbours. In its coherence, intensity, and detail, the “Postscript” is De Quincey’s most lurid investigation of violence.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

Robert Morrison is Queen’s National Scholar at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He has edited our edition of Thomas De Quincey’s essays On Murder, and his edition of De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings is forthcoming with Oxford World’s Classics next year. Morrison is the author of The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey, which was a finalist for the James Black Memorial Prize in 2010. His edition of Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published by Harvard University Press in 2011. His co-edited collection of essays, Romanticism and Blackwood’s Magazine: “An Unprecedented Phenomenon” is forthcoming with Palgrave. Read his previous blog post on John William Polidori and The Vampyre.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Newspaper illustration depicting the escape of John Turner from the second floor of the King’s Arms after he discovered the second murders December 1811. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (2) The Funeral of the Murdered Mr. and Mrs. Marr and infant Son. Published Dec 24, 1811 by G. Thompson No. 43 Long Lane, West Smithfield. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Ratcliffe Highway Murders Reward poster offering 50 pounds for information on the murders of the Marr Family, December 1811, London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (4) Procession to interment of John Williams. Published Jan’y 10 1812 by G Thomson no 45 Long Lane Smithfield. London Chronicle via Wikimedia Commons. (5) Book cover used with the author’s permission.

The post De Quincey’s fine art appeared first on OUPblog.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.

The three “On Murder” essays had a remarkable impact on the rise of nineteenth-century decadence, as well as on crime, terror, and detective fiction. De Quincey is “the first and most powerful of the decadents,” declared G. K. Chesterton in 1913, and “any one still smarting from the pinpricks” of Oscar Wilde or James Whistler “will find most of what they said said better in Murder as One of the Fine Arts.” More recently, the British television drama Whitechapel (2012) has exploited De Quincey’s fascination with the Ratcliffe Highway killings, as have authors including Iain Sinclair, Philip Kerr, and Lloyd Shepherd. “May I quote Thomas De Quincey?” asks the murderer politely in Peter Ackroyd’s Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem (1994). “In the pages of his essay ‘On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts’ I first learned of the Ratcliffe Highway deaths, and ever since that time his work has been a source of perpetual delight and astonishment to me.” Most compellingly, in his forthcoming thriller Murder as a Fine Art, David Morrell makes De Quincey the prime suspect in a series of copy-cat murders that terrify London in 1854. Morrell’s two detectives Ryan and Becker discover that De Quincey’s “Postscript” has just been published, and that in it “the Opium-Eater described Williams’s two killing sprees for fifty, astoundingly blood-filled pages — murders that by 1854 had occurred forty-three years earlier and yet were presented with a vividness that gave the impression the killings had happened the previous night.” De Quincey’s response to Williams ranged from gruesomely vivid reportage to brilliantly satiric high jinks and penetrating literary and aesthetic criticism. In his hands, violent crime became a subject which could be detached from social circumstances and then ironized, examined, and avidly enjoyed by generations of murder mystery connoisseurs and armchair detectives who enjoy the intellectual challenge, rapt exploration, and satiric safety of murder as a fine art.