new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: poty 2012, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: poty 2012 in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 12/10/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

Geography,

mars,

place of the year,

POTY,

extraterrestrial,

Social Sciences,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

outer,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Gérardine Goh Escolar,

Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law,

grubby,

Add a tag

By Gérardine Goh Escolar

The relentless heat of the sun waned quickly as it slipped below the horizon. All around, ochre, crimson and scarlet rock glowed, the brief burning embers of a dying day. Clouds of red dust rose from the unseen depths of the dry canyon — Mars? I wish! We were hiking in the Grand Canyon, on vacation in that part of our world so like its red sister. It was 5 August 2012. And what was a space lawyer to do while on vacation in the Grand Canyon that day? Why, attend the Grand Canyon NASA Curiosity event, of course!

Wait, what? Space lawyers? Have they got their grubby hands on Mars now?

Well, quite the contrary, and in a manner of speaking, space law has been working to keep any grubby hands off Mars. In the heady aftermath of the Soviet launch of Sputnik-1 in 1957, nations flocked to the United Nations to discuss — and rapidly agree upon — the basic principles relating to outer space. Just a decade later, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty was concluded, declaring outer space a global commons, and establishing that the “exploration and use of outer space shall be carried on for the benefit and in the interests of all mankind”. Today, more than half of the world’s nations are Parties to the Outer Space Treaty, and its principles have achieved that hallowed status of international law — custom — meaning that they are binding on all States, Party or not.

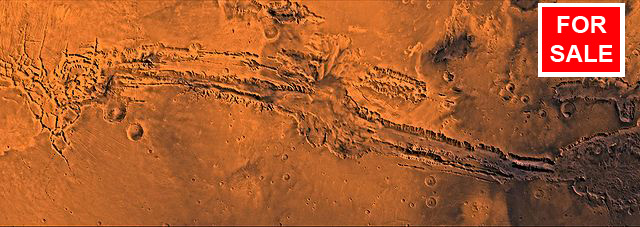

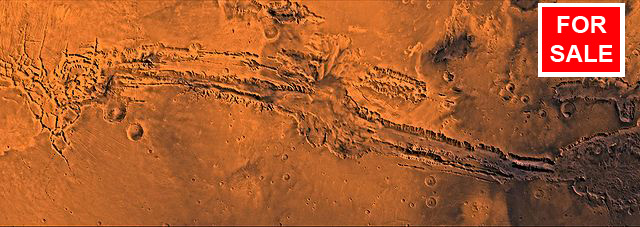

More specifically, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty affirmed that outer space, including the Moon, planets, and other natural objects in outer space (such as Mars!), were not subject to appropriation, forbidding States from claiming any property rights over them. Enterprising companies and individuals have sought to exploit what they saw as a loophole in the Treaty, laying claim to extraterrestrial land on the Moon, Mars and beyond, and selling acres of this extraterrestrial property for a pretty penny. One company claims to have sold over 300 million acres of the Moon to more than 5 million people in 176 countries since 1980. The price of one Moon acre from this company starts at USD$29.99 (not including a deep 10% discount for the holiday season) — potentially making the owner of said company a very rich man. Other companies have also started a differentiated pricing model: “The Moon on a Budget” – only USD$18.95 per acre if you wouldn’t mind a view of the Sea of Vapours — vs. the “premiere lunar location” of the Sea of Tranquillity for USD$37.50 per acre. The package includes a “beautifully engraved parchment deed, a satellite photograph of the property and an information sheet detailing the geography of your region of the moon.” Land on Mars comes at a premium: starting at USD$26.97 per acre, or a “VIP” deal of USD$151.38 for 10 Mars acres.

Indeed, the USD$18.95 may be a good price for the paper that the “beautifully engraved parchment deed” is printed on. And that is likely all you will get for your money. Although the Treaty does not also explicitly forbid individuals or corporate entities from laying claim to extraterrestrial property, it does make States internationally responsible for space activities carried out by their nationals. Despite these companies’ belief that the Treaty only prohibits States from appropriating extraterrestrial property, it is disingenuous to say that on Mars and any other natural object in outer space, “apart from the laws of the HEAD CHEESE, currently no law exists.” International law does apply to the use and exploration of outer space and natural extraterrestrial bodies, including Mars. And that international law, including the prohibition on the appropriation of extraterrestrial property, applies equally to individuals and corporate entities through the vehicle of State responsibility in international law, and through domestic enforcement procedures.

Now, that’s not to say that the principle of non-appropriation is popular. It has been questioned by a caucus of concerned publicists, worried that it would stifle commercial interest in the exploration of Mars. Some other publicists — myself included — have come up with proposals for “fair trade/eco”-type uses of outer space that they contend should be an exception to the blanket ban. But the law at the moment stands as it is — Mars cannot be owned. Or bought. Or sold. For many private ventures into outer space, that is a “big legal buzzkill.” These days, it seems, NASA may even land a spacecraft on the asteroid you purport to own and refuse to pay parking charges — and the US federal court will actually dismiss your case as without legal merit. What is the world coming to?

On the bright side, international space law has meant that there has been a lot of international cooperation in outer space. This has mostly kept the peace in outer space (no Star Wars!) and has ensured the freedom of the exploration and use of outer space for the benefit of humanity. International space law has also contributed towards keeping the Martian (and outer space) environment pristine. And in a world where we worry about the future of our own blue planet, maybe having international law keep our grubby hands of her sister Red Planet isn’t such a bad idea after all.

Dr. Gérardine Goh Escolar is Associate Legal Officer at the United Nations. She is also Associate Research Fellow at the International Institute of Air and Space Law at Leiden University, and has taught international law and space law at various universities, including the National University of Singapore, the University of Cologne and the University of Bonn. She was formerly legal officer and project manager at a national space agency, as well as counsel for a satellite-geoinformation data company. She is currently working on her fourth book, International Law and Outer Space (Oxford International Law Library, OUP: forthcoming 2014). All opinions and any errors in this post are entirely her own.

The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law is a comprehensive online resource containing peer-reviewed articles on every aspect of public international law. Written and edited by an incomparable team of over 800 scholars and practitioners, published in partnership with the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, and updated through-out the year, this major reference work is essential for anyone researching or teaching international law. Articles on outer space law, free for a limited time, include: “Moon and Celestial Bodies” ; “Astronauts” ; “Outer Space, Liability for Damage” ; and “Spacecraft, Satellites, and Space Objects”.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year competition, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Valles Marineris is a vast canyon system that runs along the Martian equator. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS. Image has been altered from the original with the addition of a “FOR SALE” sign.

The post Mars, grubby hands, and international law appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/8/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shakespeare,

Geography,

renaissance,

mars,

John Donne,

astrology,

astronomy,

marlowe,

place of the year,

Copernicus,

john evelyn,

galileo,

Humanities,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

Kepler,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Middleton,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claude Mylon,

Francois de Verdus,

Gascoigne,

Girolamo Preti,

John Skelton,

Marilyn Deegan,

Robert Burton,

Samuel Sorbière,

Thomas Hobbes,

Thomas Stanley,

William Lilly,

Literature,

Add a tag

By Marilyn Deegan

The new discoveries of the Mars rover Curiosity have greatly excited the world in the last few weeks, and speculation was rife about whether some evidence of life has been found. (In actuality, Curiosity discovered complex chemistry, including organic compounds, in a Martian soil analysis.)

Why the excitement? Well, astronomy, cosmology, astrology, and all matters to do with the stars, the planets, the universe, and space have always fascinated humankind. Scientists, astrologers, soothsayers, and ordinary people look up to the heavenly bodies and wonder what is up there, how far away, whether there is life out there, and what influence these bodies have upon our lives and our fortunes. Were we born under a lucky star? Will our horoscope this week reveal our future? What is the composition of the planets?

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences, but it was the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century that advanced astronomy into a science in the modern sense of the word. Throughout the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and others challenged the established Ptolemeic cosmology, and put forth the theory of a heliocentric solar system. The Church found a heliocentric universe impossible to accept because medieval Christian cosmology placed earth at the centre of the universe with the Empyrean sphere or Paradise at the outer edge of the circle; in this model, the moral universe and the physical universe are inextricably linked. (This is a model that is typified in Dante’s Divine Comedy.)

Authors from John Skelton (1460-1529) to John Evelyn (1620-1706) lived in this same period of great change and discovery, and we find a great deal of evidence in Renaissance writings to show that the myths, legends, and scientific discoveries around astronomy were a significant source of inspiration.

The planets are of course not just planets: they are also personifications of the Greek and Roman gods; Mars is a warlike planet, named after the god of war. Because of its red colour the Babylonians saw it as an aggressive planet and had special ceremonies on a Tuesday (Mars’ day; mardi in French) to ward off its baleful influence. We find much evidence of the warlike nature of Mars in writers of the period: Thomas Stanley’s 1646 translation Love Triumphant from A Dialogue Written in Italian by Girolamo Preti (1582-1626) is a verbal battle between Venus and her accompanying personifications (Love, Beauty, Adonis) and Mars (who was one of her lovers) and his cohort concerning the superior powers of love and war. Venus wins out over the warlike Mars: a familiar image of the period.

John Lyly’s play The Woman in the Moon (c.1590-1595) also personifies the planets and plays on the traditional notion that there is a man in the moon. Lyly’s use of the planets is thought to reflect the Elizabethan penchant for horoscope casting. The warlike Mars versus Venus trope is common throughout the period, and it appears in the works of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Middleton, Gascoigne, and most of their contemporaries. A search in the current Oxford Scholarly Editions Online collection for Mars and Venus reveals almost 300 examples. Many writers of the period also refer to astrological predictions; Shakespeare in Sonnet 14 says:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

This is thought to be a response to Philip Sidney’s quote in ‘Astrophil and Stella’ (26):

Who oft fore-judge my after-following race,

By only those two starres in Stella’s face.

Thomas Powell (1608-1660) suggests astrological allusions in his poem ‘Olor Iscanus’:

What Planet rul’d your birth? what wittie star?

That you so like in Souls as Bodies are!

…

Teach the Star-gazers, and delight their Eyes,

Being fixt a Constellation in the Skyes.

While there is still much myth and metaphor pertaining to heavenly bodies in 17th century literature, there is increasing scientific discussion of the positions of the planets and their motions. To give just a few examples, Robert Burton’s 1620 Anatomy of Melancholy discusses the new heliocentric theories of the planets and suggests that the period of revolution of Mars around the sun is around three years (in actuality it is two years).

In his Paradoxes and Problemes of 1633, John Donne in Probleme X discusses the relative distances of the planets from the earth and quotes Kepler:

Why Venus starre onely doth cast a Shadowe?

Is it because it is neerer the earth? But they whose profession it is to see that nothing bee donne in heaven without theyr consent (as Kepler sayes in himselfe of all Astrologers) have bidd Mercury to bee nearer.

The editor’s note suggests that Donne is following the Ptolemaic geocentric system rather than the recently proposed heliocentric system. In his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions of 1623 Donne castigates those who imagine that there are other peopled worlds, saying:

Men that inhere upon Nature only, are so far from thinking, that there is anything singular in this world, as that they will scarce thinke, that this world it selfe is singular, but that every Planet, and every Starre, is another world like this; They finde reason to conceive, not onely a pluralitie in every Species in the world, but a pluralitie of worlds;

There are also a number of letters written in the 1650s and 1660s between Thomas Hobbes and Claude Mylon, Francois de Verdus, and Samuel Sorbière concerning the geometry of planetary motion.

William Lilly’s chapter on Mars in his Christian Astrology (1647), is a blend of the scientific and the metaphoric. He is correct that Mars orbits the sun in around two years ‘one yeer 321 dayes, or thereabouts’, and he lists in great detail the attributes of Mars: the plants, sicknesses, qualities associated with the planet. And he states that among the other planets, Venus is his only friend.

There are few areas of knowledge where myth, metaphor, and science are as continuously connected as that pertaining to space and the universe. Our origins, our meaning systems, and our destinies — whatever our religious beliefs — are bound up with this unimaginably large emptiness, furnished with distant bodies that show us their lights, lights which may have been extinguished in actuality millenia ago. Only death is more mysterious, and many of our beliefs about life and death are also bound up with the mysteries of the universe. That is why we remain so fascinated with Mars.

Marilyn Deegan is Professor Emerita in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College, University of London. She has published widely on textual editing and digital imaging. Her book publications include Digital Futures: Strategies for the Information Age (with Simon Tanner, 2002), Digital Preservation (edited volume, with Simon Tanner, 2006), Text Editing, Print and the Digital World (edited volume, with Kathryn Sutherland, 2008), and Transferred Illusions: Digital Technology and the Forms of Print (with Kathryn Sutherland, 2009). She is editor of the journal Literary and Linguistics Computing and has worked on numerous digitization projects in the arts and humanities. Read Marilyn’s blog post where she looks at the evolution of electronic publishing.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press. The launch content (as at September 2012) includes the complete text of more than 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, including all of Shakespeare’s plays and the poetry of John Donne, opening up exciting new possibilities for research and comparison. The collection is set to grow into a massive virtual library, ultimately including the entirety of Oxford’s distinguished list of authoritative scholarly editions.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Written in the stars appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Geography,

mars,

gmo,

oxford music online,

place of the year,

OMO,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music Online,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claudio Monteverdi,

Gustav Holst,

Kyle Gann,

Add a tag

By Kyle Gann

By long tradition, sweet Venus and mystical Neptune are the planets astrologically connected with music. The relevance of Mars, “the bringer of war” as one famous composition has it, would seem to be pretty oblique. Mars in the horoscope has to do with action, ego, how we separate ourselves off from the world; it is “the fighting principle for the Sun,” in the words of famous astrologer Liz Greene. Michel Gauquelin, who conducted a statistical test for the validity of astrology, found that Mars near the ascendant or midheaven in a person’s chart correlated heavily with choosing athletics or surgery as a career: it connects to physical competition and knives. Mars also rules everything military, and thus in music it is associated mainly with percussion. Most composers have egos, but musicians are not generally a physically aggressive bunch, and fighting isn’t our area. Many a famous composer sat out World War II playing in the Army band. (In high school I was thrilled that my simply taking music classes exempted me from the gym requirement — under the institutional assumption that all music students would get enough exercise in the marching band. I was a pianist.)

Claudio Monteverdi

And so Mars, in the classical music world, has been only an occasional acquaintance. There isn’t much classical music about athletics, though Arthur Honegger did write a rather punchy tone poem called

Rugby (1928), and Charles Ives — a star baseball player in youth — portrayed a

Yale-Princeton Football Game in music around 1899 as a kind of college prank. Music specifically about surgery may have yet to appear (and let’s leave Salomé out of this). Seeking a connection between Mars and music,

Gustav Holst would probably leap to most minds, but I think first of

Claudio Monteverdi. Holst, after all, had to give all his planets equal treatment, but it was Monteverdi who invented the “stile concitato,” the agitated style, to restore in music what he saw as a warlike mode known in poetry but historically absent in music. He made his theories explicit in his scenic cantata

Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda of 1624, its poem a kind of forced sexual encounter disguised as a battle between armed rivals. Monteverdi makes it quite clear what he considered warlike tones:

lots of quick repeated notes in a harmonic stasis. And if you think about it, that description applies equally well to

“Mars” from Holst’s Planets (1914–16), with its hammering, one-note ostinato, and, as we’ll see below, to most other battle pieces as well. Considering the phenomenal evolution of the actual military, its musical signifiers have remained strikingly consistent.

Despite Monteverdi’s continued advocacy in some subsequent Madrigali guerrieri of 1638, the stile concitato did not establish itself as a broad genre. In the centuries following Il combattimento, depiction of martial action is rare enough in music for the well-known instances to be easily enumerated. The first of Johann Kuhnau’s Biblical History sonatas (1700) purports to describe David’s conflict with Goliath, once again with a profusion of quick repeated notes; also with “martial” rhythms such as streams of dotted eighths followed by sixteenths, or the snare-drum rhythm of an eighth and two sixteenths. The Battalia a 9 (1673) of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber is for only strings, but it too makes a fetish of chords in repeated notes. Its “Der Mars” movement, in addition, brilliantly asks for a piece of paper between the fingerboard and strings of the cello to make the instrument’s rhythmic drone sound plausibly like some kind of drum. Michel Corrette’s Combat Naval from his Harpsichord Divertimento No. 2 (1779) likewise starts off with repeated notes in snare-drum rhythms, and climaxes with forearm clusters that quite effectively signify cannon blasts. In Mozart’s and Haydn’s generations, even the presence of drums and cymbals was enough to suggest Turkish and thus military connotations (since what were the Turks there for, except to make war with?), as in Haydn’s “Military” Symphony, No. 100.

The advent of Romanticism, though, marked a turn at which war became demoted as a subject for serious musical treatment. Two of the 19th century’s most high-profile musical depictions — Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory (1813) and Liszt’s Hunnenschlacht (1857) — are considered among their most embarrassingly literal and superficial works. Bruckner did claim that the Plutonian finale of his Eighth Symphony (1887) depicted two emperors meeting on the field of battle, but that was rather after the fact, since he was trying to throw his lot in among the programmaticists. All this suggests, I think, distinct unease among classical musicians with things military or violent. Of course military music is sometimes appropriated to good effect, as in Berlioz’s Rakoczy March from The Damnation of Faust (1846). But despite Monteverdi’s heroic attempt to establish a martial mode, in retrospect classical attempts to depict battle tend to become anomalous oddities from history (Corrette, Biber) or humorous superficialities (Beethoven, Liszt).

Carl Nielsen

Finally, in the 20th century, the increase in dissonance and percussion brought at least a more respectable realism to battle music, though the carnage of the World Wars made anti-war statements more popular than celebrations of famous victories.

Carl Nielsen’s Fifth Symphony (1922) was a powerful response to the lunacy of World War I, with a first movement in which a solo snare drum seems determined to halt the progress of the orchestra, whose humanistic main theme finally overwhelms it. A couple of conflagrations later, Stravinsky made an anti-war statement in his

Symphony in Three Movements (1945), partly inspired by film images of goose-stepping Nazi soldiers. Less ironically, George Antheil cheered the Allies along with his

Fifth Symphony, subtitled “1942” and written that year as the fortunes of war were changing in North Africa. Shostakovich, in his

Leningrad Symphony (1941), wrote melodies to symbolize the mutual approaches of the German and Russian armies, though the German theme is arguably a rather silly one; at least, Béla Bartók took savage delight in satirizing it in his

Concerto for Orchestra. During the war even the more abstract-leaning Stefan Wolpe wrote a

Battle Piece (1943-7) for piano — once again marked by repeated notes.

The massive War Requiem (1961-2) by the pacifist Benjamin Britten, however — perhaps its century’s grandest anti-war musical protest, filled with snare-drum march rhythms and trumpet fanfares suspended in uneasy irony — seems to close a curved trajectory that opened with Monteverdi’s Il combattimento. Whereas musicians once thought the military mode in music could be innocently brought up with historical interest or patriotic pride, today we invoke it only to condemn it. The Vietnam War era may have rendered any non-pejorative expression of Mars verboten for the foreseeable future. In recent years the pianist Sarah Cahill commissioned anti-war pieces from many composers (Frederic Rzewski, Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, and Meredith Monk among them) for a project called “A Sweeter Music”; my own contribution, War Is Just a Racket, uses a 1933 text by General Smedley Butler, lamenting the army’s too-close ties to corporate interests.

Yet perhaps because Mars and Neptune were conjunct when I was born, I’ve written one un-ironic piece of battle music myself. Aside from the “Mars” movement of my own Planets (yes, I was foolhardy enough to compete with Holst, but my “Mars” is more complaining than belligerent), I depicted the battle of the Little Bighorn in my one-man electronic cantata Custer and Sitting Bull (1999), replete with sampled gunfire. The Sioux warriors are in one key, the US Cavalry in another a tritone away, and as they take turns the music jumps between two different tempos. But there’s something so peculiar about the expression of Mars in music that I have to wonder if, a couple of centuries from now, that battle scene will survive only as a curious anomaly, like Battalia a 9 or the Combat Naval or the battle of David and Goliath.

Kyle Gann is a composer who writes books about American music, including, so far; The Music of Conlon Nancarrow; American Music in the Twentieth Century; Music Downtown: Writings from the Village Voice; No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s 4’33”; Robert Ashley; and, coming up in 2015, a book on Ives’s Concord Sonata. His music explores tempo complexity and microtonality. He writes the blog, Postclassic and teaches at Bard College.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars and music appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlanaP,

on 12/4/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

david rothery,

mars,

planets,

VSI,

very short introduction,

place of the year,

gale,

POTY,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

rothery,

crater,

Geography,

curiosity,

Atlas of the World,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Environmental & Life Sciences,

Science & Medicine,

gale crater,

VSIs,

Add a tag

By David Rothery

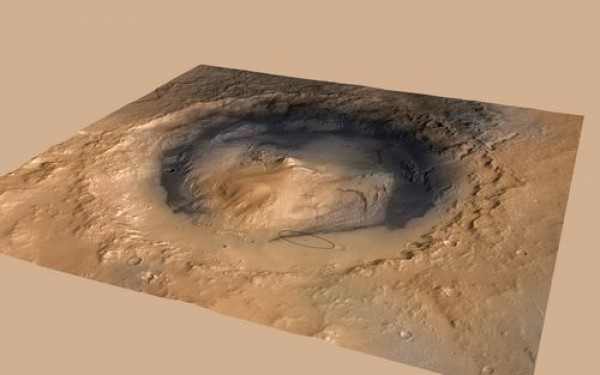

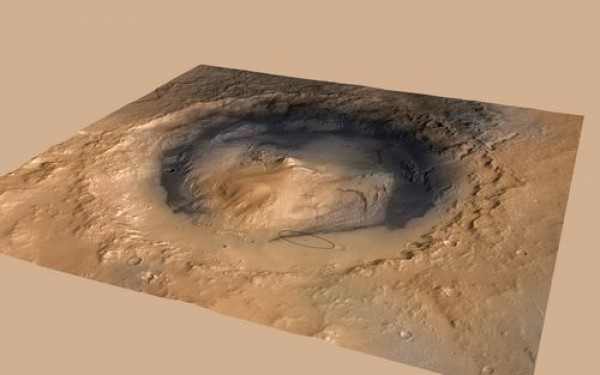

So Mars is ‘Place of the Year’! It has the biggest volcano in the Solar System — Olympus Mons — amazing dust storms, and the grandest canyon of all — Valles Marineris. Mind you, the surface area of Mars is almost the same as the total area of dry land on Earth, so to declare Mars as a whole to be ‘place of the year’ seems a little vague, given that previous winners (on Earth) have been islands or single countries. If you pushed me to specify a particular place on Mars most worthy of this accolade I would have to say Gale crater, the location chosen for NASA’s Curiosity Rover which landed with great success on 6 August.

This was chosen from a shortlist of several sites offering access to layers of martian sediment that had been deposited over a long time period, and thus expected to preserve evidence of how surface conditions have changed over billions of years. Gale crater is just over 150 km in diameter, but the relatively smooth patch within the crater where a landing could be safely attempted is only about 20 km across, and no previous Mars lander has been targeted with such high precision.

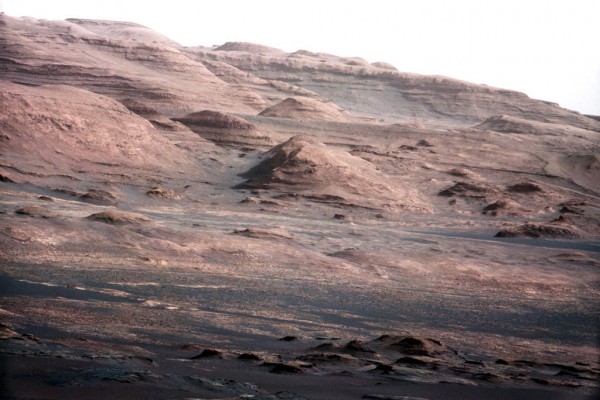

Perspective view of Gale crater. Curiosity landed in the ellipse within the nearest part of the crater. Image Credit: NASA

The thing that makes Gale one of the most special of Mars’s many craters is that its centre is occupied by a 5 km high mound, nicknamed Mount Sharp, made of eroded layers of sediment. To judge from its performance so far, the nuclear powered Curiosity Rover looks well capable of traversing the crater floor and then making its way up Mount Sharp layer by layer, reading Mars’s history as it goes. The topmost layers are probably rock made from wind-blown sand and dust. The oldest layers, occurring near the base of the central mound, will be the most interesting, because they appear to contain clay minerals of a kind that can form only in standing water. If that’s true, Curiosity will be able to dabble around in material that formed in ponds and lakes at a time when Mars was wetter and warmer than today. It will probably take a year or so to pick its way carefully across ten or so km of terrain to the exposures of the oldest, clay-bearing rocks, but already Curiosity has seen layers of pebbly rock that to a geologist are a sure sign that fast-flowing rivers or storm-fed flash-floods once crossed the crater floor.

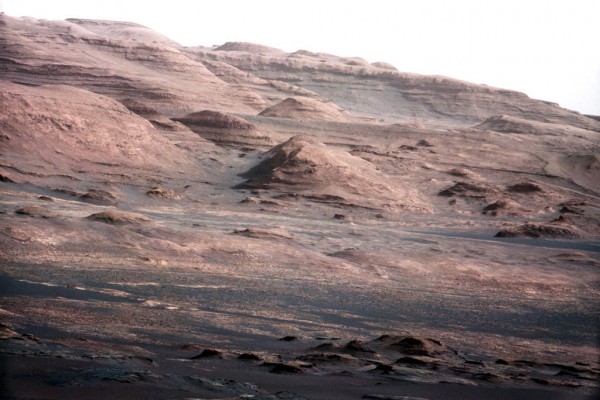

Layers at the base of Mount Sharp that Curiosity will analyze. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

The geologist in me wants to study the record of changing martian environments over time, because I like to find out what makes a planet tick. However the main reason why Mars continues to be the target for so many space missions, is that in the distant past — when those clay deposits were forming – its surface conditions could have been suitable for life to become established. Curiosity’s suite of sophisticated science instruments is designed to study rocks to determine whether they formed at a time when conditions were suitable for life. They won’t be able to prove that life existed, which will be a task for a future mission. If life ever did occur on Mars, then it might persist even today, if only in the form of simple microbes. Life probably will not be found at the surface, which today is cold, arid and exposed to ultraviolet light thanks to the thinness of its atmosphere, but within the soil or underneath rocks.

Finding life — whether still living or extinct — on another world would offer fundamental challenges to our view of our own place in the Universe. Currently we know of at least two other worlds in our Solar System where life could exist — Mars and Jupiter’s satellite Europa. It has also become clear that half the 400 billion stars in our Galaxy have their own planets. If conditions suitable for life occur on only a small fraction of those, that is still a vast number of potential habitats.

So, are we alone, or not? We don’t know how common it is for life to get started: some scientists think that it is inevitable, given the right conditions. Others regard it as an extremely rare event. If we were to find present or past life on Mars, then, provided we could rule out natural cross-contamination by local meteorites, this evidence of life starting twice in one Solar System would make it virtually unthinkable that it had not started among numerous planets of other stars too. Based on what we know today, Earth could be the only life-bearing planet in the Galaxy, but if we find independent life on Mars, then life, and probably intelligence, is surely abundant everywhere. As the visionary Arthur C. Clarke put it: “Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” Terrifying or not, I’d like to know the answer. I don’t think Mars holds the key, but it surely holds one of the numbers of the combination-lock.

David Rothery is a Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the Open University UK, where he chairs a course on planetary science and the search for life. He is the author of Planets: A Very Short Introduction. Read his previous blog post: “Is there life on Mars?”

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars: A geologist’s perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/3/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Geography,

mars,

atlas,

burma,

shortlist,

place of the year,

cartography,

myanmar,

longlist,

Atlas of the World,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

public vote,

oxford’s atlas,

Add a tag

Since its inception in 2007, Oxford University Press’s Place of Year has provided reflections on how geography informs our lives and reflects them back to us. Adam Gopnik recently described geography as a history of places: “the history of terrains and territories, a history where plains and rivers and harbors shape the social place that sits above them or around them.” An Atlas of the World expert committee made up of authors, editors, and geography enthusiasts from around the press has made several different considerations for their choices over the years.

Warming Island was a new addition to the Atlas and conveyed how climate change is altering the very map of Earth. Kosovo’s declaration of independence not only caused lines on the map to be redrawn, but highlighted the struggle of many separatists groups around the world. In 2009 and 2010, we looked to the year ahead — as opposed to the year past — with the choices of South Africa and Yemen. Finally, last year was an easy choice as South Sudan joined us as a new country.

We took a slightly different tact with Place of the Year this year. In addition to the ideas of our Atlas committee, we decided to open the choice to the public. We created a longlist, which was open to voting, and invited additions in the comments. After a few weeks of voting, we narrowed the possible selections to a shortlist, also open to voting from the public.

Four front-runners emerged in both the longlist and shortlist: London, Syria, Burma/Myanmar, and Mars. These places have changed greatly over the years, but 2012 has been a particularly special year for each. London hosted the Queen’s Jubilee and the Summer Olympics, as well as the Libor scandal and Leveson Inquiry. The Arab Spring has spread across the Middle East and North Africa, but after the toppling of dictators in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, civil war threatens to tear Syria apart. On the other side of the globe, the government of Burma (also known as Myanmar) is slowly moving to reform the country and only two weeks ago President Barack Obama made a historic visit to Rangoon. And finally, this August the Curiosity Rover landed on Mars. Although you can’t find Mars in our Atlas of the World (for obvious reasons), it captures the spirit of cartography: the exploration of the unknown and all that entails.

It was these four front-runners that we asked Oxford University Press employees to vote on and our Atlas committee to consider. Mars won the public vote, the OUP employee vote, and the hearts and minds of our Atlas committee.

Once we made our final decision on November 19th, we began contacting experts on Mars from around Oxford University Press to illuminate different aspects of the red planet. Inevitably, the first response we received asked us whether we had heard about the rumours surrounding NASA’s upcoming announcement. We took that as a good sign — and we’ll bring up An Atlas of Mars at our next editorial meeting.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

By: AlanaP,

on 12/3/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Geography,

mars,

NASA,

telescope,

curiosity,

place of the year,

hubble,

Atlas of the World,

POTY,

rover,

curiosity rover,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

mars’,

Social Sciences,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Add a tag

MARS!

It’s a city! It’s a state! It’s a country! No — it’s a planet! Breaking with tradition, Oxford University Press has selected Mars as the Place of the Year 2012.

A close-up of Mars by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. Image Credit: NASA

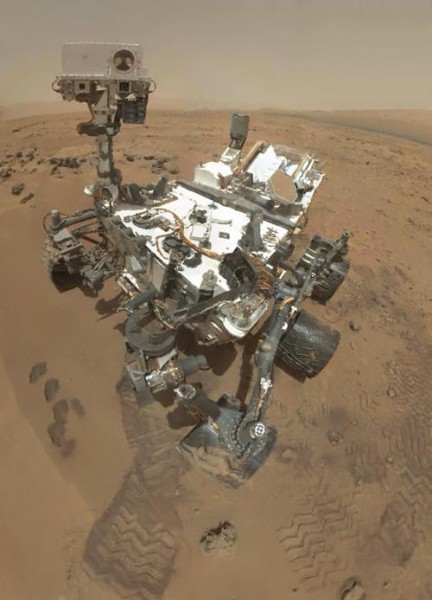

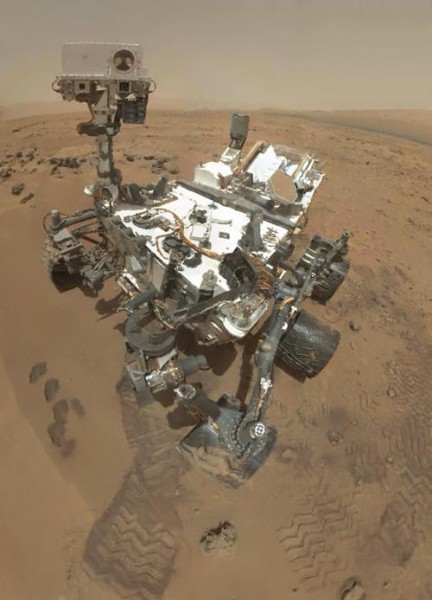

Mars, visible in the night sky to the naked eye, has fascinated and intrigued for centuries but only in the past 50 years has space exploration allowed scientists to better understand the red planet. On 6 August 2012, NASA’s Curiosity Rover landed on Mars’ Gale Crater, and by transmitting its findings back to Earth, Curiosity has made Mars a little a less alien. Among many other accomplishments, Curiosity has swallowed Martian soil and discovered an ancient stream bed. Today, NASA is expected to make a possibly mars-shattering announcement at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Mount Sharp, Curiosity Rover's goal. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

With an eye to the future of scientific discovery, Oxford University Press has chosen Mars in celebration of the place that has kept Earthlings excited and engaged this year. Your votes, combined with the votes of OUP employees, and the opinion of our expert Atlas of the World committee, easily led to Mars’s victory, outperforming Syria, London, Calabasas (California, USA), Greece, Istanbul, CERN, Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, Artic Circle, and Myanmar/Burma.

Here are some of the many reasons why we’re so excited about Mars:

- While scientists have been mapping Mars from afar since the 19th century, it still represents the new and unknown — the fascination of cartographers and atlas-makers.

- Space exploration! Astrophysics! Astronomy! Geophysics! Astrobiology! There’s much to know about the universe and Earth’s place in it, and Mars is just one fascinating piece in the puzzle.

- Mars is home to the highest peak in the Solar System (Olympus Mons), but no life forms (as far as we know).

- Space exploration poses problems for traditional international diplomacy. The Outer Space Treaty is only the beginning of a complex legal framework.

- Although named after the Roman god of war, Mars acts as a muse to some of the great writers and artists, including H.G. Wells and David Bowie.

- Did Mars Curiosity steal your iPod? Curiosity wakes up to these tracks and premiered will.i.am’s Reach for the Stars by beaming the song back to earth. Even Britney Spears wants to know more.

- Mars continues to inspire new generations to study, to dream, and to stay curious.

We’ll be looking in depth at various facets of Mars on the OUPblog this week. You can check back here for the latest posts. We invite your comments and hope that you continue to stay curious!

Curiosity Rover takes a self-portrait, reminding you to stay curious, OUPbloggers. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Malin Space Science Systems

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.