new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: outline, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 15 of 15

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: outline in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Chloe Aridjis,

Jenny Offill,

Samantha Harvey,

Catherine Lacey, Rachel Cusk: Lately I've been reading authors like these, women unafraid of breaking form or muddying expectations, women writing sentences that scour. They are books in which the characters choose, in some way, to be alone—to isolate themselves inside their own thoughts, to sever themselves from social conventions, to tell stories that, without resort to war or torture, somehow carry knives.

This morning I finished reading

Outline, Rachel Cusk's story of—well—what is it, exactly? It is the story of a writer who has gone to Greece for a week to teach; yes, it is that, at one level. But mostly it is about a woman who moves through the world under the assault of other people's stories. People who find themselves, in her presence, talking through the cyclone of their own lives, presenting themselves as they wish to be presented, asserting their right (right?) to be heard, smudging and aggrandizing, begging to be understood, until, ultimately, their stories devolve into self-circling harangues. The people our narrator meets, the people who natter on, hardly need to be encouraged. Given room to talk, they do, exhibiting, ultimately, that something selfish, stingy, mean of propulsive monologue. We have all been on the other side of such a thing. We understand. There is almost a comedy to it.

But Cusk is after far more than a set piece, a commentary on rampant self-absorption. Cusk ratchets the ambush of monologue to high tension in

Outline. She makes, of these disconnected interludes, a story with an arc. She uses her scheme to explore essential questions about the lies we tell ourselves, the responsibilities we negate, the desire we have to blame other people for the unhappiness we feel or the success we have not had or the mess we have made of marriages or parenting. Her narrator is a woman who "did not, any longer, want to persuade anyone of anything." She is a woman rarely asked about herself, but when she does comment on the stories she is told, she brings an outsiderly wisdom, a pausing perhaps. We know the outlines of who she is (a writer, a divorcee), in other words, but far more important is how we come to know what she thinks.

Here, for example, she is responding to an insufferable woman's complaints about marriage:

I replied that I wasn't sure it was possible, in marriage, to know what you actually were, or indeed to separate what you were from what you had become through the other person. I thought the whole idea of a 'real' self might be illusory: you might feel, in other words, as though there were some separate, autonomous self within you, but perhaps that self didn't actually exist. My mother once admitted, I said, that she used to be desperate for us to leave the house for school, but that once we'd gone she had no idea what to do with herself and wished that we would come back.

Here the narrator muses on desire:

I said that, on the contrary, I had come to believe more and more in the virtues of passivity, and of living a life as unmarked by self-will as possible. One could make almost anything happen, if one tried hard enough, but the trying—it seemed to me—was almost always a sign that one was crossing the currents, was forcing events in a direction they did not naturally want to go, and though you might argue that nothing could ever be accomplished without going against nature to some extent, the artificiality of that vision and its consequences had become—to put it bluntly—anathema to me. There was a great difference, I said, between the things I wanted and the things I could apparently have, and until I had finally and forever made my peace with that, I had decided to want nothing at all.

A rosy world view this is not. Easy entertainment—it's not that, either. But it is fierce and different and part of a new world order in fiction written by women. A movement to which I think we must pay quite close attention.

Among the various challenges we writers face is believing in the job we've given ourselves to do (for no one but us, let's be honest, requires us to take the storytelling burden/privilege on).

In her writing about Rachel Cusk in this week's

The New Yorker (January 5, 2015), Elaine Blair explores Cusk's own growing uneasiness about the literary enterprise:

Since the early nineties, she has reliably published a novel or a memoir every few years. But in an interview with the Guardian last August, Cusk said that she had recently come to a dead end with the modes of storytelling that she had relied on in her earlier novels. She had trouble reading and writing, and found fiction "fake and embarrassing." The creation of plot and character, "making up John and Jane and having them do things together," had come to seem "utterly ridiculous."

Blair goes on to write of the novelists who today speak of "trying to expand the possibilities of the novel" by "incorporating the techniques of memoir and essay, of hewing closer to the author's subjective experience, of effacing the difference between fiction and their own personal nonfictions." Blair then asks: "Haven't novelists always put autobiographical material to use in novels? Haven't we been reading about a character called 'Philip Roth' for years?"

I am easily accused of personalizing my fiction—doesn't matter where (Berlin, Seville, Florence, Juarez, a mental institution, a cortijo) or when (1876, 1871, 1983) the story takes place. I've never known whether that makes my stories more or less ridiculous, never imagined myself trying (in that way) to expand the possibilities of the novel; these personalized fictions are just the only stories I've held within, or been capable of writing through.

But I wonder how it is for you. How much of you is inside your fiction. How you protect yourself from drawing the conclusion that the conjuring of story lines is finally ridiculous?

eBook Sale: August 26-31 only $0.99/regular $5.99

Available at these eBook stores

Mims House eBookStore

Nook

Kindle

Kobo

iBookstore

Available at these eBook stores

Mims House eBookStore

Nook

Kindle

Kobo

iBookstore

AUDIO BOOK (Unabridged): Now Available!

Available at these Audio Book stores

iTunes Store

Amazon

Audible

iTunes Store

Amazon

Audible

So, I have a general outline of my story but the writing still isn’t flowing. I realized that I need to break down major events into smaller sections, so I will know what to write.

I’ve gone through two stages of plotting or outlining, each one getting more specific. Here’s an example:

1. First, I stared with major plot points:

A volcano threatens to blow up, so Jake gets alien Rison technology to make it stop.

2. Second, I start to layout possible scenes.

At one point, he realizes he needs the alien technology, so he makes arrangements to get it. I wrote this: Later, at home, Jake contacts Mom, who gives him a contact on Rison who can ship him some technology and he orders what he needs to counter-attack the technology Cy used. Keeping up his volunteer work, Jake goes kayaking with Bobbie Fleming.

At this level, a scene may be summarized in a single sentence. However, it’s more helpful to break down both sentences further.

3. On the third pass, I’m looking to split up the action into several scenes, or at least flesh out the one scene a bit better.

Later, at home, Jake contacts Mom, who gives him a contact on Rison who can ship him some technology and he orders what he needs to counter-attack the technology Cy used. Conflict with Mom because he really wants to try swim team and she’s distracted b/c negotiations going so badly.

Keeping up his volunteer work, Jake goes kayaking with Bobbie Fleming. Bobbie Fleming, a harbor seal upsets Jake’s kayak. Of course, he has no problem with righting the canoe and getting back in and getting back to shore. But something nags at him, the waters feel more like home than the Gulf waters did. Something about being IN Puget Sound—there was something THERE. He had to find out what?

Plot is a way of examining story to see its underlying structure. Starting with a general idea and subdividing toward a specific plot often gives a writer the direction needed for the story to work.

Snowflakes and Phases

Need a more structured approach to something similar? The Snowflake Method, by Randy Ingermanson is a very structured approach that starts with a single sentence, and then splits that into two sentences, the two into four sentences, etc. until the story takes shape. It’s a structured outlining process with built-in steps for developing characters. Randy has a Ph.D. in theoretical physics, and his structured thinking shows in this method, which he’s turned into a software program and various books. If you need a very structured program, you may like the help you’ll get from the Snowflake Method.

Another option for approaching plot in a structured way is Lazette Gifford’s Phases system. You should read her original article about Phases here. She suggests that you write a numbered list of “phases” or short summaries of action. These can be scenes, transitions, thinking about what just happened and so on.

What I like here is the reference to the overall novel. Gifford suggests that you use MSWord’s auto-numbering feature to write phases for your novel.

For example, if you want to write 50,000 words, Gifford, in her free ebook, Nano for the New and Insane, breaks the 50,000 word length into phases:

- 60 Phases in the outline — 834 words per phase — 2 phase sections per day

- 120 Phases in the outline — 417 words

per phase — 4 phase sections per day

- 150 Phases in the outline — 334 words per

phase — 5 phase sections per day

- 300 Phases in the outline — 167 words

per phase — 10 phase sections per day

In other words, I can start with 60 phases and in that space, I should have a synopsis of the the beginning, middle, and end of the story. Or, if you’d rather, think of it as Acts 1, 2, and 3. Act 1 and 3 get about 15 phases each, which leaves 30 for Act 2.

That is comforting to me. I ONLY have to decide on 15 scenes (or discrete units) for Act 1. Act 1 looms HUGE for me, but 15 scenes sounds easy.

Phases allows me to do an easy, early check on the plot, too. Each phases needs moments of high arousal: excitement, inspiration, awe, anger, humor, action, disgust or outrage. Across the phases, I can easily check on how a subplot fits into the overall structure and how the subplot progresses.

Sixty phases is something that’s easy to see and understand. Once those are set, I may try to increase to 120 words, breaking down the plot into more specific actions.

If you’re doing NaNoWriMo, this also makes the task of 50,000 words in one day much easier.

Another thing I like about the Phase method is that it’s easy to see progress. I’m all about numbers and keeping score. On 9/5, I started with 23 phases; today, I’m up to 49 phases. My goal is 60 phases by the end of the week. Then I’ll look at it further to see if I want to go for 120 or if the 60 will be good enough to write from.

.

How do you take an idea to a book? I am just starting the process again and every time, it overwhelms me. I know the process works, but it seems so daunting at this first stage. So, I only look forward to the next task, knowing that taking the first step will lead me onward.

For this story, I’ll approach it on several levels at once:

Outlining. This is the fourth book in an easy-reader series, so I know the general pattern that the book will follow over its ten chapters. Chapter one will introduce the story problem and chapter ten will wrap it up. That leaves eight chapters and each has a specific function in this short format. Chapter 2 introduces the subplot, chapter 4 intensifies it and chapter 6 resolves it. That leaves chapters 1, 3, 5, 7-10 for the wrap-up. Chapters 9 and 10 are the climax scene, split into two, with a cliff hanger at the end of chapter 9. In other words, I can slot actions into the functions of each chapter and make it work. Knowing each chapter’s function makes it easier–but not automatic. I’ll still need to shift things around and make allowances for this individual story.

Character Problem. Making my characters hurt is the second challenge. Squeezing them, making them uncomfortable, making them cry, dishing out grief and mayhem–it’s all part of the author’s job. I tend to be a peace-maker and find this to be quite difficult. But if I can manage to bring my character’s emotions to a breaking point by chapter 8, I’ll be able to move the reader. I’ll be searching for the pressure points for the character as the outline progresses. Hopefully, the emotional resolution in chapter 9-10 will be a twist, something unexpected by the reader.

Back and Forth Between Outline and Characters. The nice thing about focusing on just this much at first is that it is interactive. I’ll go back and forth between plot, character and the structure demanded by this series until the story starts to gel. Will it be easy and automatic? Oh, no. I’ll be pulling out my hair (metaphorically) for a couple days. But by the end of the week (I hope) there will be progress.

How do you start your story? Do you free-write, create a character background, or outline? Which parts interact as you create the basis for a new story?

What Character Are You? Click to Enlarge. Photo Credit: http://www.flickr.com/photos/bk/12392396893/

Use Outlines to Revise Fiction

Organization of a nonfiction piece of writing is paramount. Ideas and/or should build upon each other is an inevitable progression that leads to understanding. For fiction, the outline is the plot structure, events unfolding in an inevitable progression that lead to entertainment. When you use a narrative structure for creative nonfiction, with the curious blend of information and entertainment, the structure is doubly important. Just as the purpose of fiction and nonfiction differ, so do our organization methods.

Yet, I still find that outlining is an effective revision strategy for fiction. I don’t use it to plan fiction, but to revise. And maybe the word “outline” is wrong. Because what I do is record what I have already done.

Yet, I still find that outlining is an effective revision strategy for fiction. I don’t use it to plan fiction, but to revise. And maybe the word “outline” is wrong. Because what I do is record what I have already done.

The problem is the disconnect between what we intend–a fantastic story–and what we produce–a disappointing draft. What is in our heads is always better, and therefore, it is what we remember when we look at at draft. But it is not what is on the paper. We need some way of forcing ourselves to look, really look, at what is on the paper. Did you really make yourself crystal clear at all points? No, you did not. The connecting bits are still in your head, I guarantee it.

At this point, two things might help: feedback from astute readers or outlining, or careful observation of words on the page. Doesn’t matter to me which you use first, but you should use both methods. Today, I’m assuming that you’re going to do the outlining.

You’ll find many methods to outline a narrative structure. To use outlining as a revision strategy for a novel, I like to print out a single-spaced copy and just read through. You must base this outline on what you wrote, not on what you thought you wrote. Read your story!

Most writers have their story divided into chapters, but you can work with scenes or any other natural division. Write one sentence about what happened in each chapter. One and only one. Outlines look at the top level of organization, not the fine details. If you find that you can’t describe a chapter in one sentence, then it’s probably not focused enough yet, it’s a muddy telling of the story.

Once you have the sentence outline written, you can look through:

Inevitable progression: Is there an inevitable progression of some sort? Do things become increasingly difficult for your main character?

Main story v. subplot: Does the main story dominate the sentence outline? Do subplots integrate into the story, creating more tension and interest?

This is the place to make sweeping changes, move chapters, omit chapters, add chapters. This top-level look at your story can reveal structural problems for you to resolve in the next revision.

|

Random Acts of Publicity DISCOUNT:

$10 OFF The Book Trailer Manual.

Use discount code: RAP2011

http://booktrailermanual.com/manual

Guest post by Carol Fisher Saller

Writing Eddie’s War, which consists of 76 prose-poem vignettes, wasn’t easy. I’ve chronicled elsewhere the trouble I got myself into by writing the scenes every which-way in random order without first outlining a plot or getting to know my characters. I’d think of a scene and write it—mostly little slices of life. Here’s a short one:

Writing Eddie’s War, which consists of 76 prose-poem vignettes, wasn’t easy. I’ve chronicled elsewhere the trouble I got myself into by writing the scenes every which-way in random order without first outlining a plot or getting to know my characters. I’d think of a scene and write it—mostly little slices of life. Here’s a short one:

May 1939

Sarah Mulberry

In the first grade

she was Sam,

not even all that much

a girl.

Smile as wide as her feet were long,

feet made for puddle-jumping,

fence-hopping,

running from boys.

She could bat a ball and fling a cob

with the rest of us.

In junior high, though,

she became Sarah,

still flashing that smile,

but avoiding the cob fights.

Unless she was

provoked.

Sometimes I’d think of a new character and write a scene for him or her. Sometimes I’d build a scene around something that happened in the 1930s or 1940s, like the crash of the Hindenburg, or the invasion of Poland, or the movie Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

This is a terrible way to write a book. But I did have a few characters who kept coming back to me, and two or three story lines that began to emerge. The character of Eddie started speaking in the first person. And I at least had some historical facts in the background that forced a measure of chronology.

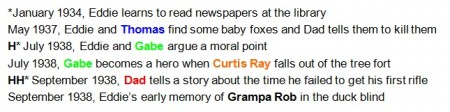

And that’s when my group came up with the sentences. (Actually, as I remember it, I was the one who thought it up, and since I’m the one blogging here today, I’m sticking to that.)

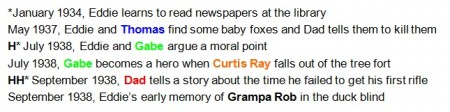

Plot with summary sentences.

The idea is to write a single sentence for each scene or chapter in your book. Include the main plot point and the name of every character who appears in a memorable way:

January 1934, Eddie learns to read newspapers at the library.

May 1937, Eddie and Thomas find some baby foxes and Dad tells them to kill them.

July 1938, Eddie and Gabe argue a moral point.

July 1938, Gabe becomes a hero when Curtis Ray falls out of the tree fort.

September 1938, Dad tells a story about an early experience with a shotgun.

September 1938, Eddie remembers Grampa Rob in the duck blind.

(and so forth)

My list took a couple of pages. Then, in order to see the organization more clearly, I used a different color to highlight each character’s name. (I didn’t color Eddie, since he’s in every scene.)

Standing back a little to look at one color/character at a time, I could see where there were gaps if a character had been away too long. To fix it, I could either move the scenes around or write ne

Author Elizabeth Spann Craig has written both ways and gives her pros and cons of each method.

http://mysterywritingismurder.blogspot.com/2011/07/my-wrap-up-of-outlining.html

Which camp do you fall into? Do you plan your novel extensively before you write a single word? Or, do you improvise as you go along?

A friend is starting a new novel at the same time I’m working on a new novel and it’s interesting to see the difference in our approach.

Character. He’s all about character and says that he just tries to set up the characters, then get out of the way and let them do things. He creates them intuitively. He doesn’t want to know what comes next because that would be boring.

Character. He’s all about character and says that he just tries to set up the characters, then get out of the way and let them do things. He creates them intuitively. He doesn’t want to know what comes next because that would be boring.

I like character, too, but can’t get my characters to work without getting to know them pretty well, by which I mean, some deliberate reflections about who they are and how they would react in different situation. I want to know how the character fits into the plot, the setting, the overall tone, the voice, the imagery–then, I can start writing.

Plot. My friend rarely worries about plot. He has some ideas about where the story will go, but seems to be able to relentlessly push the characters into conflict.

I like knowing the ending and some of the high points before I start. It’s not a complete, obsessive, scene-by-scene synopsis; but it’s some structure. Again, I like having some gestalt–an overarching idea of the story–and how this piece fits into the bigger picture.

Big Picture or Seat-of-your-Pants?

Of course, either way works for that first draft. I believe that in the revision phase, you DO have to take a look at the big picture to make sure everything fits into place.

First drafts are about getting the story on paper, however you need to. Revisions are about putting the story into the most dramatic format possible, so the reader sticks with you for the whole story.

So, however you want–just get the story on paper.

During the baby stages of Book #1, I visited countless bookstores and researched extensively online to learn that fantasy, paranormal and futuristic novels are extremely popular amongst young adult readers. It was a no-brainer, I thought, to follow suit of these trendy styles and create an intriguing story that would capture the minds of high school students. But the more I tried to incorporate these elements (vampires, werewolves, fairies and hocus pocus) into my outline, the faster my story fell apart. I quickly became overwhelmed and even contemplated throwing in the towel.

After several hours of brainstorming, I thought of stories I enjoyed as a teenager: S.E. Hinton's The Outsiders, Lois Lowry's Number the Stars, and Louisa May Alcott's Little Women , none of which had hocus pocus elements and eventually became bestsellers. These stories had one thing in common: they dealt with realistic issues that grabbed the reader's attention on the very first page.

It didn't take long for me to realize, however, if I was going to pour my heart and soul into writing a novel, then I needed to include elements that resonated with today's youth. Therefore, it seemed only natural to gear my project around the stories I enjoyed reading as a teenager: multilayered, realistic fiction.

So, when opportunity knocked, I was in the final weeks of a long-term maternity leave position at a school in Gilbertown, AL and knew there were no teaching units available for the remainder of the school year. I decided this was the perfect chance to get Book #1 in the best shape possible and begin querying agents. In other words, I didn't just quit my day job to pursue a career in writing. Unfortunately, it chose me!

You see, instead of allowing my circumstances to get me down, I remained persistent and took advantage of every spare minute of my day (usually during the children's naps and late at night) to finish Graduate School and seek representation for my first novel.

In the weeks, months, maybe years to come, I'm hopeful that young readers, librarians, teachers and YOU will have the opportunity to fall in love with my multilayered, realistic novel as much as I have. For all the support and encouragement you've given thus far, I appreciate it greatly and hope you continue to follow along as I write about this exciting journey in my life!

Have a wonderful Thursday, everyone! Tory

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 10/16/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

how to write a novel,

outline,

confidence,

NaNoWriMo,

plan,

resource,

first drafts,

first draft,

revise,

Add a tag

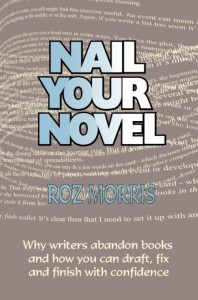

Review of

Nail Your Novel by Roz Morris

British author and writing teacher Roz Morris has a new book out just in time to help you with that first draft of your new novel. You know, the one you’re going to write in November for National Novel Writing Month, better known as NaNoWriMo.

Hiccups in your Confidence and Motivation

Morris writes with great wit and wisdom about the writing process, starting with those awkward moments when you actually admit, “Yes, I’m, uh, writing, well, you know, something a bit longer. Maybe, a, uh, a novel.”

Writing always begins here, by acknowledging the writer as a person with the usual insecurities. Morris address this directly by providing you with some structure. No, structure isn’t for everyone, but for beginners, structure can be a comfort and save them a lot of time. Her process involves a series of tasks, breaking down the process into smaller steps:

- Task 1: Shaping your inspiration

- Task 2: Starting this specific novel

- Task 3: Focused research

- Task 4: A structural survey for you novel

- Task 5: Detailed synopsis

- Task 6: How to free your muse and turn off your inner critic

- Task 7: Before you look at your manuscript again

- Task 8: The beat sheet game

- Task 9: Revising your manuscript

- Task 10: Your submission process

Help for NaNoWriMo writers

Authors embarking on the month-long adventure of writing 50,000 words in November will appreciate the first few tasks. Morris gives you direction on how to thicken the plot, find inspiration, decide what does NOT belong in the book, accept random input, and generally get the overall story thought out.

Research (Task 3) can flesh out details further:

“Research might throw up all sorts of interesting situations. For instance, I was commissioned to write a novel about people selling kidneys in India. Reading about the poverty in the villages inspired the start of the story – a young girl decides to sell her kidney to get her family out of debt. Of course, once she’s in the clutches of the butchers, she changes her mind, poor love. Meanwhile, her family are desperate to get her back.”

Overall, Morris’ experience enhances the book. This is a process she is intimately acquainted with and daily practices. Even if you’re experienced, I recommend the book as a review for concepts you already know. Because I think you’ll also find some unexpected nuggets. And for more nuggets, read Roz Morris’ blog, Dirty White Candy (Yes, a strange name for a blog, you say. Morris explains it on her home page). Example of her posts: How to Make Readers Root for Your Character

NaNoWriMo Special!

NaNoWriMo Special!

For three weeks, until 21 October, you can download the e-book of Nail Your Novel for 99p! That’s a whopping £2 off the usual price of £2.99. So if you’re preparing a book for NaNoWriMo this will help you firm up your plans, fill your plot holes – so you are ready to blast off on 1 November with confidence. Just click on the pic!

Related posts:

- Writing AND Revising Your Novel

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 7/15/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

plot holes,

deepen,

Maass,

Zuckerman,

story,

plot,

cliches,

outline,

how to,

Add a tag

In parts 1 & 2, I discussed 8 ways to plot. This last plotting idea is about deepening and extending the effectiveness of a plot.

9. Success Plot Enhancers.

There are two books which stand out, not for their overall structure of a novel, but for deepening the impact of a novel: Donald Maass’ Writing the Breakout Novel (and the accompanying workbook, Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook) and Writing the Blockbuster Novel by Albert Zuckerman.

Overall shape. Part of their strength is taking an overall look at the shape of the novel and making sure that all the parts match up. Does the beginning set up the end?

Overall shape. Part of their strength is taking an overall look at the shape of the novel and making sure that all the parts match up. Does the beginning set up the end?

Go past cliches. But they also force you to think deeper and reach for the answers that are less glib, but more true. These are actually less about plot and more about craftsmanship and commitment to excellence. And, by the way, success.

30-page outline. Specifically, Zuckerman’s insistence on a written outline of about 30 pages is interesting because it allows you to see major plot holes. His discussion of a sample outline allows you insights into some of his basic assumptions about story: for example, the antagonist and protagonist must meet in direct conflict in the climax. These assumptions seem to be largely unwritten anywhere in the literature of plotting and can only be inferred from Maass and Zuckerman. To the extent they lay bare the assumptions of great literature, they are vastly helpful.

Comments? That’s my take on the ways of plotting as taught by some of the best writing teachers. What have I left out? Which plotting methods work best for you?

Books Mentioned in This Series

- Bickham, Jack. Scene & Structure

- Card, Orson Scott. Character & Viewpoint

- Dunne, Peter Emotional Structure: Creating the Story Beneath the Plot

- Field, Syd.

- Maass, Donald. Writing the Breakout Novel

- Maass, Donald. Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook

- Noble, June & William. Steal this Plot.

- Scofield, Sandra. The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer.

- Swain, Dwight.Techniques of the Selling Writer

- Tobias, Ronald. 20 Master Plots

- Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey.

- Vorhaus, John. The Comic Toolbox.

- Zuckerman, Albert. Writing the Blockbuster Novel.

Websites Mentioned in This Series

Next: Plotting software

Related posts:

- Plot: Characters v. Patterns

- 4 More Plot Variations

- How to Use Scenes to Plot

By:

Darcy Pattison,

on 4/3/2009

Blog:

Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novel,

character,

revision,

outline,

organize,

emotional arc,

narrative arc,

plot,

plan,

YWriter,

recommended software,

SpaceJock,

Add a tag

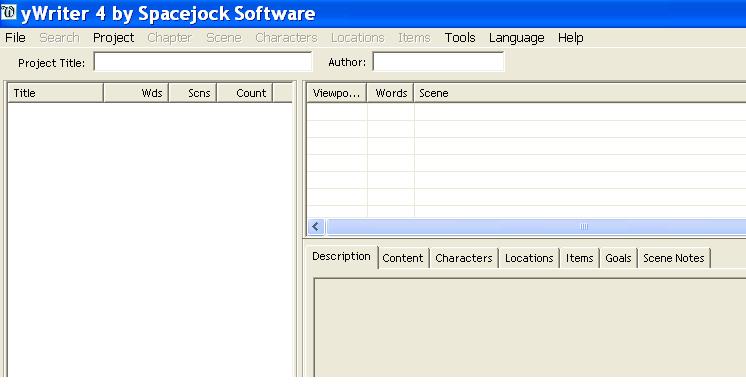

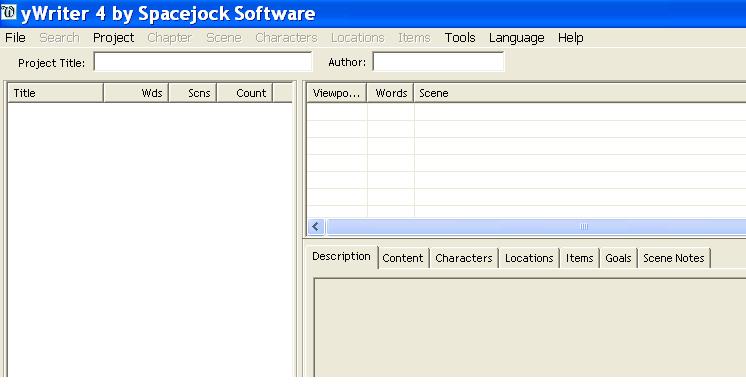

While my WIP novel is out with readers, I thought I’d look at my process for this novel and how it differed from others.

Writing Process for Novels Vary Widely

Writing process varies. First, my process was different for this novel. I find this to be always true, that what worked for one novel, won’t work for the next. In general the steps are the same, but I spend more time on one step, or do them in different orders.

Compensate for weakness. I did some evaluation of my novel ideas, works-in-progress novels, failed novels, and successful novels. I am a very private person; I’ll post information all day long, but rarely will I post anything personal. Frankly, it’s none of your business. Unfortunately, I carry that attitude over to my novels and the most common response is that “I failed to be engaged by the characters.” Of course. It’s none of your business!

So, I went looking for ways to improve the emotional life of my characters and found several helpful books and ideas on a character’s emotional arc.

Find software to support needed improvement. One suggestion on emotional arc was to use index cards to plot, writing ideas for one scene per card. Then, turn the card OVER and on the back, write the character’s emotional state during the scene. In other words, plan the character’s emotional arc.

I’ve used many different ways of plotting and I’ll tell you, never has index cards worked for me. I’ve used spreadsheet plotting and I like it very much. So, I simply added a column for the emotional state of the characters. It did work, but somehow, it didn’t seem to get me moving through the story well.

Enter YWriter, a free program that helps you plan and organize a novel. This time, since I wanted to do a better job of planning, especially the characters’ inner lives, YWriter was fabulous. It has logical and helpful screens that lay out the scenes, plots, who is present in the scene, setting, and I even found a place on the character tabs to add in the emotional reactions.

(Click to enlarge screen shot.)

(Click to enlarge screen shot.)

After planning, YWriter has screens where you can actually write the novel, in a pared down word processor (import/export is easy in rtf file formats, compatible with any word processor).

I found that part of my process stayed the same. I plan and plan, then write, only to find that about halfway through, I have to stop and replan, because the writing has changed so much. Halfway through this novel, I stopped and had to replan. But this time, it seemed too tedious to go back and update every screen in YWriter; I abandoned the program and went back to my word processor alone, with occasional reference back to the YWriter plot.

YWriter was a good experience for me and I’ll probably use it again, because it allowed me to organize so much in one centrally located file. Will I use it next time? I don’t know. I may go back to spreadsheet plotting. But I know I was glad to expand my novel writing tool box with this great program.

Post from: Revision Notes

Revise Your Novel!

Copyright 2009. Darcy Pattison. All Rights Reserved.

Related posts:

- 4 Files to Prevent Mistakes

- Spreadsheet plotting

- Revising the Outline

I finally made it to the end of my unofficial participation in National Novel Writing Month – four days late. I started on Nov. 3 and vowed to work on my rewrite every day for 30 days. As I’m ending on Dec. 7, I must have missed four days in the past 30. Can I do every day in December? With Christmas in there, I doubt it. But I’m going to do my best.

My rewrite is still coming along nicely. My outline/timeline is still making things much easier, and I even changed something in the outline today. But all the changes are making the novel better, so that’s exciting. Today, I blended some more scenes to fit their new place in the outline, and tomorrow my plan is to change the location of one scene to a location I set up in a new early scene that I wrote a couple of days ago.

How’s your writing coming? What are you working on?

Write On!

You finish your rough draft. Now what? How do you write an effective second draft of your story rather than just edit what you've already written or simply move words around?

I have a few tips.

1) Fill out a Scene Tracker for your project. Scenes that fulfill all seven essential elements of plot -- date and setting, character emotional development, is driven by a specific character goal, shows dramatic action, is filled with conflict, tension, suspense or curiosity, shows emotional change within the scene, and carries some thematic significance -- keep. Any scenes that do not fulfill each of these elements may not carry enough weight to belong in your story.

Evaluate your Scene Tracker for your strengths and weaknesses. If you find your Scene Tracker has lots of Dramatic Action filled with conflict, tension, and suspense, but little Character Emotional Development, in your rewrite, concentrate on your weakness.

For those scenes that do not fulfill each of the seven essential elements, see if you can integrate more of them in your rewrite or consider lumping together two or more weak scenes in order to make one powerful scene.

2) Create a new Plot Planner for your story. Locate the three most important scenes -- the End of the Beginning, the Crisis, the Climax. Evaluate how many scenes fall above and below the line. Consider how the energy rises and falls. The visual representation of your project should give you clues as to where to concentrate during the rewrite.

3) Write a brief outline of your story by chapter -- simply one or two sentences per chapter that will gives a feel for pacing, plot, and flow. The process of writing the outline should start to reveal holes and weaknesses throughout.

4) Write a one-page synopsis of your story.

Of course, you can always sign-up for a Plot Consultation. I'll let you know where to concentrate the next time around.

How do you go about preparing for a rewrite? What is your favorite method for "seeing" the whole of your story in order to evaluate what's needed for the rewrite???

Overall shape. Part of their strength is taking an overall look at the shape of the novel and making sure that all the parts match up. Does the beginning set up the end?

Overall shape. Part of their strength is taking an overall look at the shape of the novel and making sure that all the parts match up. Does the beginning set up the end?

Great post. I think we should always write what we love, and trust that if we write it realistically by todays standards, others will love it too. :)

Hi, Angela! I'm so glad you agree that writing is an emotional impulse. Unfortunately, I learned the hard way that it's best if one stays true to themself not only as a person, but also as a writer. It's nice to know I'm not alone on this principle. :-)