Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the third one, following The Act of Killing and Hannah Arendt.

By Roberta Seret

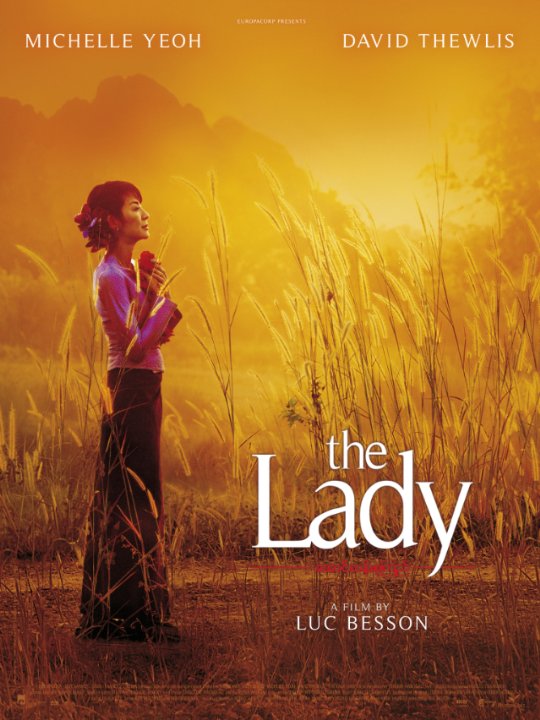

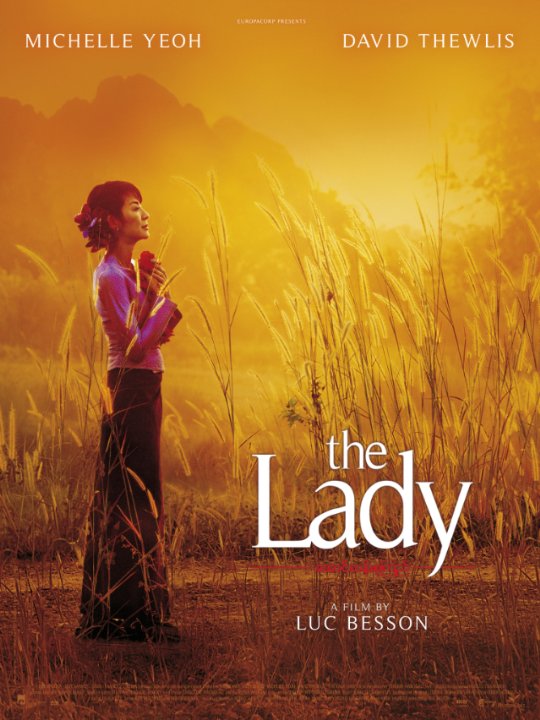

When Luc Besson finished filming The Lady in 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi had just been released from being under house arrest since 1989. He visited her at her home in Yagoon with a DVD of his film as a gift. She smiled and thanked him, responding, “I have shown courage in my life, but I do not have enough courage to watch a film about myself.”

The recurring tenet of the inspiring biographical film, The Lady, is exactly that: one woman’s courage against a military dictatorial regime. Each scene reinforces her relentless fight to overcome the inequities of totalitarianism.

Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child of General Aung San, leader of Burma during World War ll and Father of Independence from British rule. He was assassinated in 1947 before he saw his country’s sovereignty in 1948. His daughter has dedicated her life to continue his legacy – to bring democracy to the Burmese people.

The film, The Lady, begins in Oxford 1988 where she is a housewife and mother of two sons. After setting the stage of happy domesticity, she receives a phone call from her mother’s caretaker in Burma that the older woman is dying. And so begins the action.

After 41 years, Suu Kyi returns home to a different world than she remembers. The country’s name is changed from Burma to Myanmar, Ragoon has become Yagoon, and a new capital, Naypidaw, has been carved out of a jungle. Students are demonstrating and being killed in the streets of Yagoon while General Ne Winn rules with an iron fist. Suu Kyi is soon asked by a group of professors and students to form a new party, the National League for Democracy. She campaigns to become their leader.

French director, Luc Besson, was not allowed to film in Myanmar. Instead, he chose Thailand at the Golden Triangle, where Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand merge in a beautiful mountainous landscape. Most of his interior scenes, however, take place at the Lady’s house on Inya Lake in Yagoon, which Luc Besson recreated with help from Google Earth and computers. The Chinese actress, Michelle Yeoh, plays Suu Kyi, with perfectly nuanced facial and body expressions that are balanced with a subtle combination of emotion and control. But the Burmese, who were initially not allowed by the government to see the film, resented a Chinese actress portraying their icon. Even the police chased Ms. Yeoh from Myanmar when she tried to pay her respects to the Lady.

The film adheres closely to history and biography, which are inherently compelling. The director did not need to borrow from fiction to enhance his portrait of a brave, self-sacrificing woman. Luc Besson is a master filmmaker, and we see in the characters of his strong women, like Nikita (1990) and The Lady, the power of will and determination that go beyond limits to become personality cults.

The film depicts how Suu Kyi wins 59% of the votes in the general election of 1990, but instead of leading Parliament as Prime Minister, she has already been forced and silenced under house arrest by the Military where she stays for more than 15 years and three times in prison until 2010.

The Lady is a heart-breaking story of a woman’s personal sacrifice to free her people from the Military’s crimes against humanity. In 2012, once free and allowed to campaign, she won 43 seats in Parliament for her party, but this is only 7% of seats. She will campaign again in 2015 despite the Military’s opposition and a Constitution that has already been amended to block her from winning.

In Luc Besson’s film, we see a beautiful woman of courage and heart, a personage deserving the adulation of her people. “She is our hope,” they all agree. “Hope for Freedom.”

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Roberta has written a longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Lady: One woman against a military dictatorship appeared first on OUPblog.

Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the first one.

By Roberta Seret

American director, Joshua Oppenheimer, has merged theatre, psychology, and film in his innovative documentary, The Act of Killing, Jagal in Indonesian, meaning Butcher. (BAFTA Award for Best Documentary of 2013.)

We are taken to Indonesia 1965 when more than 500,000 citizens and thousands of Chinese residents were massacred because they were communists or communist sympathizers or born Chinese.

By 1965, there were 3 million communists in Indonesia and they had the strongest communist party outside the Soviet Union and China. During this time, the political and economic situation throughout the Archipelago was unstable with an annual inflation of 600% and impoverished living conditions. General Soeharto overthrew Soekarno, took control of the army and government, and led a ruthless anti-communist purge.

For eight years (2003-2011), director Joshua Oppenheimer, lived in Indonesia, learned the language, and set himself to expose in cinema this untold genocide.

The Act of Killing recreates scenes of mass execution in Indonesia from 1965-66. The main actor, Anwar Congo, and his auxiliary protagonist, Adi Zulkadry, are perpetrators from the past who re-enact their crimes. In reality, during 1965, they were both gangsters who were promoted from selling black market movies to leading death squads in North Sumatra. Anwar, before the camera, boasts that he killed approximately 1,000 people by strangling them with wire. “Less blood that way. Less smell,” he reminisces with a smile.

The initial question for the director is what structure to choose for his documentary? How to recreate this history 47 years later on the screen to viewers who will learn about these horrors for the first time?

Oppenheimer has been influenced by Luigi Pirandello’s structure as found in the play, Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921). Pirandello’s theatre of a play within a play merges drama and psychology (psychodrama/ group therapy). And Oppenheimer, a true master, takes this form to cinema. He becomes the leader, director of the action, and asks questions to his actors so they can re-enact the history. In turn, the actors use props and improvisation to respond. Scenes unfold in unpredictable ways and the actors, without realizing it, are taken back to the past. This structure of psychodrama is the director’s secret vehicle to open up the subconscious of his characters and free their suppressed memory.

For Oppenheimer, as for Pirandello almost 100 years before, it is Art that becomes a conduit for Truth. It is Art that reveals the Reality between the Self and the outside world. Oppenheimer has achieved this on a stage while filming his actors. He uses Pirandello’s role playing and re-experiencing to expose the truth to the actors and to the world about Indonesia’s horrific genocide and impunity for such crimes.

After Anwar and his co-actors voyage deep into their past, we see them as they see themselves – criminals with blood on their hands, monsters overwhelmed with fear that the ghosts of the past will curse them.

At the end of the journey, Anwar becomes victim. The act of filming the act of killing has made him realize the 1,000 deaths he had committed. The line between acting and reality becomes blurred and there is only one Truth that emerges.

Anwar’s last scene is his response to this intense journey. He gives us a guilt-ridden soliloquy reminiscent of Shakespeare and a scene of vomiting where he tries to purge himself of his victims’ blood. Oppenheimer does not rush this scene. He lets the power of film take over as the camera documents for history the criminal’s realization that he is a Butcher of Humanity.

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Roberta has written a longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Psychodrama, cinema, and Indonesia’s untold genocide appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy International Children’s Book Day! When their father goes away unexpectedly, Roberta, Peter and Phyllis have to move with their mother from their London home to a cottage in the countryside. Thus begins E. Nesbit’s The Railway Children, the latest in our Oxford Children’s Classic series, which we’ve excerpted below.

Father had been away in the country for three or four days. All Peter’s hopes for the curing of his afflicted engine were now fixed on his father, for Father was most wonderfully clever with his fingers. He could mend all sorts of things. He had often acted as veterinary surgeon to the wooden rocking-horse; once he had saved its life when all human aid was despaired of, and the poor creature was given up for lost, and even the carpenter said he didn’t see his way to do anything.

And it was Father who mended the doll’s cradle when no one else could; and with a little glue and some bits of wood and a penknife made all the Noah’s Ark beasts as strong on their pins as ever they were, if not stronger.

Peter, with heroic unselfishness, did not say anything about his engine till after Father had had his dinner and his after-dinner cigar. The unselfishness was Mother’s idea—but it was Peter who carried it out. And needed a good deal of patience, too.

At last Mother said to Father, ‘Now, dear, if you’re quite rested, and quite comfy, we want to tell you about the great railway accident, and ask your advice.’

‘All right,’ said Father, ‘fire away!’

So then Peter told the sad tale, and fetched what was left of the engine.

‘Hum,’ said Father, when he had looked the engine over very carefully.

The children held their breaths.

‘Is there no hope?’ said Peter, in a low, unsteady voice.

‘Hope? Rather! Tons of it,’ said Father, cheerfully; ‘but it’ll want something besides hope—a bit of brazing say, or some solder, and a new valve. I think we’d better keep it for a rainy day. In other words, I’ll give up Saturday afternoon to it, and you shall all help me.’

‘Can girls help to mend engines?’ Peter asked doubtfully.

‘Of course they can. Girls are just as clever as boys, and don’t you forget it! How would you like to be an engine-driver, Phil?’

‘My face would be always dirty, wouldn’t it?’ said Phyllis, in unenthusiastic tones, ‘and I expect I should break something.’

‘I should just love it,’ said Roberta—’do you think I could when I’m grown-up, Daddy? Or even a stoker?’

‘You mean a fireman,’ said Daddy, pulling and twisting at the engine. ‘Well, if you still wish it, when you’re grown-up, we’ll see about making you a fire-woman. I remember when I was a boy—’

Just then there was a knock at the front door.

‘Who on earth!’ said Father. ‘An Englishman’s house is his castle, of course, but I do wish they built semi-detached villas with moats and drawbridges.’

Ruth—she was the parlour-maid and had red hair—came in and said that two gentlemen wanted to see the master.

‘I’ve shown them into the library, sir,’ said she.

‘I expect it’s the subscription to the vicar’s testimonial,’ said Mother, ‘or else it’s the choir holiday fund. Get rid of them quickly, dear. It does break up an evening so, and it’s nearly the children’s bedtime.’

But Father did not seem to be able to get rid of the gentlemen at all quickly.

‘I wish we had got a moat and drawbridge,’ said Roberta; ‘then, when we didn’t want people, we could just pull up the drawbridge and no one else could get in. I expect Father will have forgotten about when he was a boy if they stay much longer.’