By Mark Lawrence Schrad

If Ukraine is a volatile tinderbox of political instability, the situation in its Russian-speaking east is even more dangerous: a tinderbox drenched in vodka. Aspirations and allegiances aside, the most striking contrast between the pro-European protests on Kyiv’s Maidan square and the pro-Russian, anti-Maidan protests in the east is not simply that the latter tend to be armed and forcibly occupying government buildings (rather than protesting outside of them), but also that they have a higher likelihood of being drunk and disorderly, making the situation dramatically more volatile.

Especially amidst revolution, vodka and AK-47s don’t mix, especially in Russia and Ukraine.

Lost amidst all the talk of ethnic, linguistic, and cultural ties between Ukrainians and Russians at play in the Donbass area of southeastern Ukraine, the culture of alcoholism seems almost too cliche to garner mention; yet perhaps it explains all too well the different political trajectories in Ukraine’s east and west.

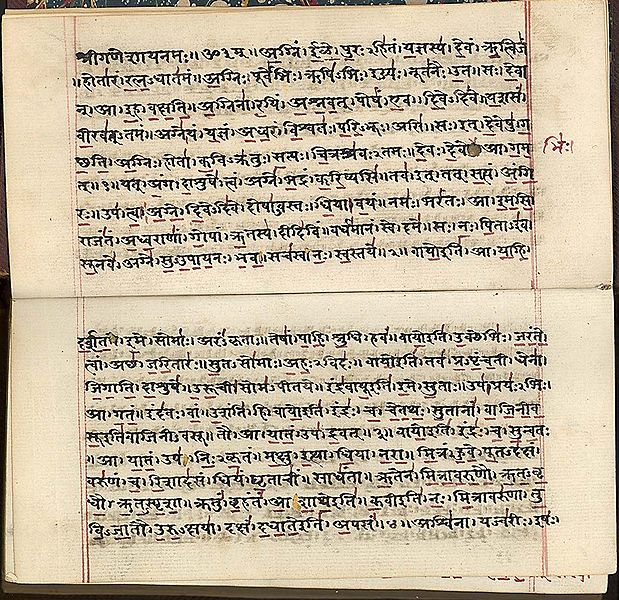

By Andreas Argirakis, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Today, both Russia and Ukraine consistently rank atop of the world’s heaviest drinking nations. Unlike moderate wine- and beer-drinking countries, they also share a “traditional vodka drinking culture,” marked by heavy intoxication, binge drinking of hard liquor, and a general acceptance of the public drunkenness that results. These patterns are not hard-wired into the DNA of Russians or Ukrainians. Instead, they are the result of centuries of autocratic rule under the Russian empire and its Soviet successor, both of which used vodka to debauch society at the expense of the state. Unfortunately, the revolutionary experiences that both the Russians and Ukrainians shared as part of those empires—most notably in 1917 and 1991—were heavily influenced by alcohol, in conditions that bear eerie similarities to the present circumstances in Ukraine.

* * *

Already three years into total war, and suffering widespread desertions from the front, in early 1917 Tsar Nicholas II was rapidly losing control of his country. Hearing word that his military would no longer follow orders—which included firing on its own unarmed civilians protesting in the streets—Nicholas hurried from the front line back to Petrograd to reassert control. He never made it. His train was stopped by mutinous soldiers and railway workers, who forced the tsar’s abdication in the February Revolution of 1917.

With the police in hiding or defying orders, Petrograd mobs laid siege to police stations and government ministries. Armed gangs looted homes, shops, and liquor stores. Some commandeered motor cars—which they promptly crashed, since few knew how to drive, especially through a haze of pilfered vodka. Hundreds died, and thousands more were injured in the February Revolution, yet there was a sense that things could have been much worse, were it not for the tsar’s prohibition decree at the outset of the war. “If vodka could have been found in plenty, the revolution could easily have had a terrible ending.”

With the tsar gone, political power lay with a weak Provisional Government led by Aleksandr Kerensky, while de facto power lay with the self-organized councils of workers and soldiers who manned the streets. With more demoralizing drubbings at the front, continued economic chaos, and the inability to broadcast power much beyond the walls of the Winter Palace, by October 1917, virtually no one was willing to defend the Provisional Government against the growing power of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

The night of 24-25 October 1917 was relatively quiet, as the Bolsheviks discreetly took control of strategic assets: government offices, train stations, and telegraph posts. The Winter Palace itself was stormed by a relatively small and disorganized group of revolutionaries, many of whom bypassed the priceless artworks and looted instead the imperial wine cellars. Loud pops punctuated the Petrograd night—more often champagne corks than gunfire—while the snows snows were stained red: not with blood, but with burgundy wine.

Understanding that vodka was the means by which the old capitalist order enriched itself while keeping the worker drunk and subservient, Lenin and the early Bolsheviks were steadfast prohibitionists. Their equation of alcohol with “counterrevolution” was only reinforced by a series of drunken riots and pogroms in the streets of the capitol, which threatened their own tenuous hold on power. “What would you have?” the exasperated People’s Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky, told a reporter. “The whole of Petrograd is drunk!”

“The bourgeoisie perpetuates the most evil crimes,” Lenin wrote to Felix Dzerzhinsky in December 1917, “bribing the cast-offs and dregs of society, getting them drunk for pogroms.” Lenin ordered that Dzerzhinsky’s newly formed All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combatting Counterrevolution and Sabotage—the “Cheka”—confront the vodka threat by any means necessary. All alcohol stores were to become property of the state, bootleggers were to be shot on sight, and wine warehouses were to be blown up with dynamite. And they were.

“The very nearest future will be a period of heroic struggle with alcohol,” proclaimed Leon Trotsky, the firebrand ideologue and founder of the Red Army. “If we don’t stamp out alcoholism, then we will drink up socialism and drink up the October Revolution.” Red Guard and Cheka detachments sworn to be “sober and loyal to the revolution” fought pitched street battles against unruly mobs and drunken military detachment—with heavy casualties on both sides—not only in in Petrograd and Moscow, but Saratov, Tomsk, Nizhny Novgorod, and beyond. Russia paid a heavy price for its drunkenness and disorder in the throes of revolution. Other legacies were even more nefarious: Dzerzhinsky’s Cheka security force was subsequently rebranded the NKVD and later the KGB—the secret police force complicit in the darkest days of Soviet totalitarianism.

* * *

While prohibition in the Soviet Union died with Vladimir Lenin, the KGB and the Soviet dictatorship endured another seven decades. While 1989 saw the peaceful end of the Cold War and the euphoric toppling of the Berlin Wall, the communist autocracy lurched ahead for another two years in the Soviet Union itself. Amid economic chaos and political dissatisfaction, the liberation of the East European satellite states emboldened nationalists in the Soviet Baltic, Caucasus, Ukrainian, and even Russian republics. With pressures for national self-determination threatening to tear the Soviet Union apart, Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a new treaty that would remake the USSR into something of a confederation, bequeathing sovereignty to the autonomous national republics. For Soviet hardliners this was too much to bear.

On 19 August 1991—the day before the new treaty—a hard-line “State Emergency Committee” led by Vice President Gennady Yanayev staged a coup d’etat: imposing martial law and putting Gorbachev under house arrest at his Crimean retreat.

The previous night, both Yanayev and Prime Minister Valentin Pavlov had been out drinking with friends when they were summoned to the Kremlin by KGB chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, who set the plan in motion. “Yanayev wavered and reached out for the bottle,” Gorbachev later wrote in his Memoirs. Along with the other conspirators, it is doubtful that Yanayev was sober at any time during the bungled three-day coup.

Co-conspirator Defense Minister Dmitry Yazov later confirmed that not only was Yanayev “quite drunk,” but so too were other plotters: KGB head Kryuchkov, Interior Minister Boris Pugo, and even Yazov himself. After chasing his blood pressure medications with alcohol, Prime Minister Pavlov had to be pulled unconscious from the bathroom. After that, “I saw him two or three times, and each time he was dead drunk,” Yazov testified. “I think he was doing this purposefully, to get out of the game.”

Drunk or not, the conspirators somehow forgot to neutralize their primary rival: the populist Boris Yeltsin, who’d just been elected president of the Russian republic—the largest and most important of the fifteen republics that constituted the USSR.

Yeltsin—whose own intemperance later became the stuff of legend—rallied his supporters at the legislature of the Russian Republic (the “White House”), where protesters were busy constructing protective barricades. Nonviolent protestors convinced the Soviet tank troops surrounding the White House to defect and instead defend Yeltsin and the Russian republic. In an iconic moment captured by the global news media, Yeltsin—defying threats of sniper fire—courageously clamored atop a tank turret to address the crowd, denouncing the coup and calling for a general strike. In those delicate moments when the whole country teetered on the brink of civil war, Yeltsin sternly rebuked offers of vodka, claiming “there was no time for a drink” at this moment of supreme crisis.

Yeltsin’s sober command stood in stark contrast to the coup leaders in the Kremlin—just a few miles to the east—where the irresolute putschists confronted a restive media at an ill-fated press conference. “A sniffling Gennady Yanayev, his face swollen by fatigue and alcohol, had a tough time fielding the combative questions,” recalled Russian history professor Donald J. Raleigh. “His trembling hands and quivering voice conveyed an image of impotence, mediocrity, and falsehood; he appeared a caricature of the quintessential, boozed-up Party functionary from the Brezhnev era.” That’s precisely who he was.

In the face of growing opposition and a military unwilling to follow orders, the coup collapsed on 21 August. Rather than surrender to the police, Interior Minister Pugo chose to shoot his wife before turning the gun on himself. Others sought refuge in the bottle: Prime Minister Pavlov was drunk when the authorities came to arrest him, “but this was no simple intoxication,” attested Kremlin physician Dmitry Sakharov, “He was at the point of hysteria.” When the incoherent Yanayev was carried out of his Kremlin office—its floor strewn with empty bottles—he was too drunk to even recognize his one-time comrades who had come to arrest him. Hours later, when President Gorbachev returned safely to Moscow, he’d effectively landed in a different country. Thanks to Yeltsin’s leadership in bringing down the hardline coup, legitimacy lay with Russia and the other union republics rather than Gorbachev’s USSR. The subsequent legal dissolution of the Soviet Union was only a formality.

* * *

What does this drunken history lesson have to do with the ongoing crisis in Ukraine? Quite a bit, actually. Both 1917 and 1991 demonstrate how political protests instantly become more complex and dangerous when mixed with a culture of extreme inebriation and general apathy toward public drunkenness. Moreover, given their shared imperial/Soviet cultural inheritance (including alcohol abuse) Ukraine is only slightly less immune from these revolutionary dynamics than is Russia.

While much ado has been made of Ukraine’s (arguably overblown) ethnic and linguistic divisions between the pro-EU, Ukrainian west and the pro-Russian east; there are palpable demographic divisions between east and west Ukraine. While on the whole, Ukraine’s health indices are lower than its European neighbors, the demographic situation deteriorates as you move from west to east across the country. Ukraine’s western provinces—which spent less time under the sway of the Russian/Soviet empires—generally have higher rates of fertility, lower rates of mortality, and higher average life expectancy than those eastern regions that have longer history of Russian domination. Perhaps not surprisingly, the eastern Donbass regions exhibiting the highest mortality and lowest life expectancy are also by far the hardest-drinking regions of an already hard-drinking nation, with cultural acceptance of inebriation most aligned with the Russian “norm” to their east. It may be only a rough approximation, but the further east you go in Ukraine, the more dangerous this revolutionary stage becomes.

So is it any surprise that—in Ukraine’s ongoing struggles between east and west—we should see different approaches to vodka, and the potential for destabilization that it presents first in Kyiv, then in Donetsk?

For context: in 2004, a horribly rigged election favoring the pro-Russian, Donetsk-based Viktor Yanukovych prompted a backlash of popular opposition, which culminated with massive protests on Kyiv’s Independence Square, or Maidan Nezalezhnosti. Building an encampment on the Maidan, the nonviolent protesters—often in excess of 100,000—endured the brutal winter to rally for free elections. Relenting to the popular demands of this so-called “Orange Revolution,” new elections swept in triumphant, pro-European factions. Unfortunately for Ukraine’s lackluster economy, these once allied political factions squabbled and split, while succumbing to Ukraine’s chronic corruption. The split in the pro-European bloc opened the door for the once-vanquished Yanukovych to emerge victorious in the freely-contested presidential election of 2010.

While in the long term the Orange Revolution may have ended in failure, in the short term, it provided perhaps the best exemplar of an effective, nonviolent, post-Soviet political protest, not the least because alcohol was explicitly forbidden in the sprawling tent cities as a bulwark against the easily foreseen drunken disturbances that were sure to result.

When the pro-European protesters again took to the Maidan against Yanukovych’s corrupt presidency in November 2013, their self-organized security forces put a premium on maintaining tranquility through sobriety. “If someone is drunk, he is out of here,” explained Evgeni Dudchenko, a security volunteer on the square, “Alcohol is forbidden here, and we don’t need any hooligans.”

That the Euromaidan protests—like those a decade earlier—remained peaceful for as long as they did can partly be attributed to this enforced sobriety. Even when the movement turned violent in the face of ever-tighter government crackdowns, culminating in the indefensible slaughter of civilian protesters by government gunmen on 22 February, there is a sense that—as with Russia’s February of 1917—Ukraine’s February Revolution could have been much, much worse. A mob of inebriate protesters meeting a drunken security battalion armed to the teeth could have multiplied the carnage many times over.

Following the government’s spilling the blood if its own people on that fateful day, the Ukrainian parliament impeached President Yanukovych, who by that time had already fled the country. Filling the leadership void in Kyiv was a weak interim government that is effectively unable to broadcast political power across the country, as evidenced by Russia’s subsequent non-invasion invasion of Crimea, and the destabilization of the Donbass and the Russian-speaking east.

Even after Yanukovych had been toppled and the regime’s police and military forces had melted away, the major confrontations—and even shootouts—between competing, armed Maidan factions had their roots in drunken disagreements. Still, at the very least, in the midst of a potentially revolutionary situation, the protesters on the Maidan acknowledged, confronted, and mitigated the potential destabilization from vodka, making the protests there far less dangerous than they could have been.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the more recent armed occupations in Ukraine’s heavy-drinking Donbass region that constitute the “anti-Maidan” movement. Beginning 6 April 2014 in the eastern cities of Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Luhansk, small numbers of violent activists—armed with everything from homemade clubs to firearms—clashed with local police, stormed and occupied regional administration buildings and other strategic installations, demanding greater political autonomy from Kyiv, and in some cases outright annexation by Russia in a repeat of the scenario in Crimea.

These protests differed not only in terms of aims and means, but also temperament. In Kharkiv, local residents complained that the protesters were not local, but rather that they were drunken hooligans dispatched from Russia to infiltrate and destabilize their town and intimidate their residents. Ukrainian special forces succeeded in clearing the separatists there, but not before they vandalized and torched the place, leaving behind a mess of garbage and empty liquor bottles. Yet the most noteworthy confrontations came further south in Donetsk—the former stronghold of ousted president Yanukovych.

In Donetsk, violent protesters fought their way into the local administration building, and displaced the Ukrainian flag with the black, blue and red tricolor of their newly declared “People’s Republic of Donetsk.” In a scene eerily reminiscent of the accounts of the drunken State Emergency Committee back in 1991, the organizers of this self-proclaimed mini-state in Donetsk appear to have done so while staggeringly drunk.

From the first clashes with police outside the building, many in the pro-Russian mob were drunk, in stark contrast to the sobriety of the Maidan. The party, it seems, continued once the separatists occupied the building, where thirty protesters were found completely drunk, and empty bottles of vodka, whisky, and tequila littered the stairways to the meeting rooms where the independent Donets Republic was proclaimed.

Manning the barricades outside the occupied Donetsk City Hall: armed protesters wandered freely, “while people lit fires in the street and drank beer and vodka.” Both outside the building and within, secessionists accosted the media while visibly drunk.

In his series of incredible reports from the region, Vice News reporter Simon Ostrovsky noted that at the beginning of “day two of the People’s Republic of Donetsk, it smells like there’s been a huge frat party here.” In something of a throwback to the press conference of the shaky State Emergency Committee, Ostrovsky then interviewed the leader of the Donetsk “Coordination Council” Vadim Chernyakov, who slurred through his speech, visibly hung over and slurring his speech—even admitting as much, apologizing for his “headache” as his eyes rolled back in his head.

It didn’t take long for the separatists to re-learn the historical lesson that alcohol and guns don’t mix in a revolutionary scenario: after recovering from their hangovers, the leadership decreed that the defenders of the building should dump all of their vodka and “follow a prohibition law” to maintain some semblance of order in such tumultuous times.

Still, in dispelling the false equivalence between the Maidan and anti-Maidan forces, the cultural context cannot be overlooked. “Unlike the pro-Europe protest movement in Kiev,” reports the New York Times, “the stirrings in Donetsk have so far attracted little support from the middle class and seem dominated by pensioners nostalgic for the Soviet Union and angry, and often drunk, young men.”

Whether or not discipline holds in Donetsk and throughout the Ukrainian east is yet to be seen, as Kyiv tries—in fits and starts—to reassert control over violent Russian-minded secessionists and local pro-autonomy protesters. Yet the task of all sides looking to bring stability to the region is made infinitely more difficult by the unpredictability generated by the region’s alcoholic inheritance. Recent events have demonstrated as much, as Vasily Krutov—the head of Kyiv’s counter-terrorism operation in the Donetsk region—was almost torn apart by a mob of Kramatorsk locals, some who were visibly intoxicated. Even more troubling—in one of his last dispatches before being kidnapped by the pro-Russian separatists in Slovyansk—Ostrovsky chronicled how a handful of the most drunken and agitated anti-Maidan protesters stumbled onto the Kramatorsk airbase, manned by heavily armed and understandably jittery soldiers. Such drunken provocation could easily have ended in tragedy—one that could have provoked even greater backlash locally, and even a pretext for greater Russian intervention in Ukraine.

The lamentable reality is that—in such times of revolutionary change and political crisis—we overlook that “cliche” of vodka only at our own peril.

Mark Lawrence Schrad is Assistant Professor of Political Science, Villanova University and author of Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Tinderbox drenched in vodka: alcohol and revolution in Ukraine appeared first on OUPblog.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Interesting. I kinda took the guy bonding stuff for granted, was more impressed by the kick-ass heroine. Also the fact that he could make a chess game exciting.

BTW, did you know Benioff is the screenwriter for the new Wolverine movie?

I did know! It really stoked the nerd fire I've been cultivating for that movie. And yes, that was a pretty kick-ass heroine, though I think the structure of the story (with the dramatic climax coming to a close with Kolya, and the epilogue addressing the lady-friend) puts the focus on them boys.