Inspired by a true story, One Step at a Time exposes the unfortunate reality of the global landmine crisis through the prism of a friendship between a young boy and an elephant. Writer Jane Jolly and artist Sally Heinrich handle this subject with such deftness and clarity to ensure young readers grasp the predicament facing […]

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Burma, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 14 of 14

Blog: Perpetually Adolescent (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Elephants, thailand, burma, Sally Heinrich, Book Reviews - Childrens and Young Adult, one step at a time, Jane Jolly, landmines, Books, friendship, book review, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

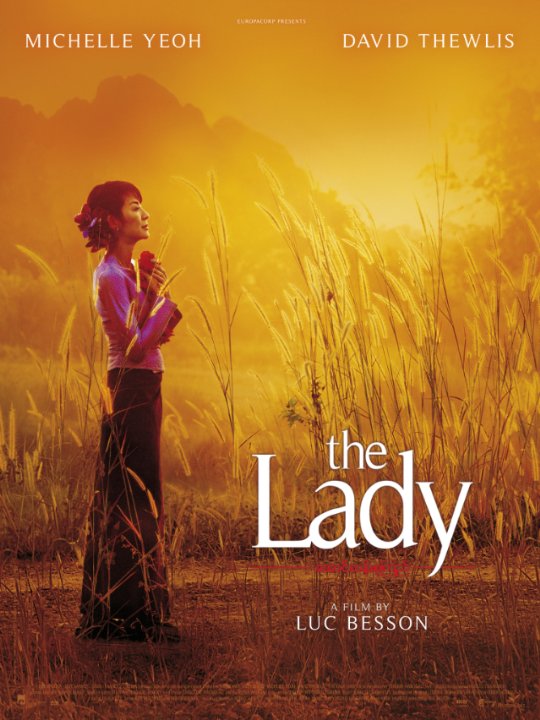

JacketFlap tags: burma, pil, myanmar, Michelle Yeoh, *Featured, TV & Film, oxford journals, roberta, public international law, Roberta Seret, seret, JICJ, Journal of International Criminal Justice, arendt, Luc Besson, The Lady, yagoon, besson, yeoh, Law, Journals, Aung San Suu Kyi, Add a tag

Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the third one, following The Act of Killing and Hannah Arendt.

By Roberta Seret

When Luc Besson finished filming The Lady in 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi had just been released from being under house arrest since 1989. He visited her at her home in Yagoon with a DVD of his film as a gift. She smiled and thanked him, responding, “I have shown courage in my life, but I do not have enough courage to watch a film about myself.”

The recurring tenet of the inspiring biographical film, The Lady, is exactly that: one woman’s courage against a military dictatorial regime. Each scene reinforces her relentless fight to overcome the inequities of totalitarianism.

Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child of General Aung San, leader of Burma during World War ll and Father of Independence from British rule. He was assassinated in 1947 before he saw his country’s sovereignty in 1948. His daughter has dedicated her life to continue his legacy – to bring democracy to the Burmese people.

The film, The Lady, begins in Oxford 1988 where she is a housewife and mother of two sons. After setting the stage of happy domesticity, she receives a phone call from her mother’s caretaker in Burma that the older woman is dying. And so begins the action.

After 41 years, Suu Kyi returns home to a different world than she remembers. The country’s name is changed from Burma to Myanmar, Ragoon has become Yagoon, and a new capital, Naypidaw, has been carved out of a jungle. Students are demonstrating and being killed in the streets of Yagoon while General Ne Winn rules with an iron fist. Suu Kyi is soon asked by a group of professors and students to form a new party, the National League for Democracy. She campaigns to become their leader.

French director, Luc Besson, was not allowed to film in Myanmar. Instead, he chose Thailand at the Golden Triangle, where Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand merge in a beautiful mountainous landscape. Most of his interior scenes, however, take place at the Lady’s house on Inya Lake in Yagoon, which Luc Besson recreated with help from Google Earth and computers. The Chinese actress, Michelle Yeoh, plays Suu Kyi, with perfectly nuanced facial and body expressions that are balanced with a subtle combination of emotion and control. But the Burmese, who were initially not allowed by the government to see the film, resented a Chinese actress portraying their icon. Even the police chased Ms. Yeoh from Myanmar when she tried to pay her respects to the Lady.

The film adheres closely to history and biography, which are inherently compelling. The director did not need to borrow from fiction to enhance his portrait of a brave, self-sacrificing woman. Luc Besson is a master filmmaker, and we see in the characters of his strong women, like Nikita (1990) and The Lady, the power of will and determination that go beyond limits to become personality cults.

The film depicts how Suu Kyi wins 59% of the votes in the general election of 1990, but instead of leading Parliament as Prime Minister, she has already been forced and silenced under house arrest by the Military where she stays for more than 15 years and three times in prison until 2010.

The Lady is a heart-breaking story of a woman’s personal sacrifice to free her people from the Military’s crimes against humanity. In 2012, once free and allowed to campaign, she won 43 seats in Parliament for her party, but this is only 7% of seats. She will campaign again in 2015 despite the Military’s opposition and a Constitution that has already been amended to block her from winning.

In Luc Besson’s film, we see a beautiful woman of courage and heart, a personage deserving the adulation of her people. “She is our hope,” they all agree. “Hope for Freedom.”

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Roberta has written a longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Lady: One woman against a military dictatorship appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Geography, mars, atlas, burma, shortlist, place of the year, cartography, myanmar, longlist, Atlas of the World, POTY, Social Sciences, *Featured, Place of the Year 2012, poty 2012, public vote, oxford’s atlas, Add a tag

Since its inception in 2007, Oxford University Press’s Place of Year has provided reflections on how geography informs our lives and reflects them back to us. Adam Gopnik recently described geography as a history of places: “the history of terrains and territories, a history where plains and rivers and harbors shape the social place that sits above them or around them.” An Atlas of the World expert committee made up of authors, editors, and geography enthusiasts from around the press has made several different considerations for their choices over the years.

Warming Island was a new addition to the Atlas and conveyed how climate change is altering the very map of Earth. Kosovo’s declaration of independence not only caused lines on the map to be redrawn, but highlighted the struggle of many separatists groups around the world. In 2009 and 2010, we looked to the year ahead — as opposed to the year past — with the choices of South Africa and Yemen. Finally, last year was an easy choice as South Sudan joined us as a new country.

We took a slightly different tact with Place of the Year this year. In addition to the ideas of our Atlas committee, we decided to open the choice to the public. We created a longlist, which was open to voting, and invited additions in the comments. After a few weeks of voting, we narrowed the possible selections to a shortlist, also open to voting from the public.

Four front-runners emerged in both the longlist and shortlist: London, Syria, Burma/Myanmar, and Mars. These places have changed greatly over the years, but 2012 has been a particularly special year for each. London hosted the Queen’s Jubilee and the Summer Olympics, as well as the Libor scandal and Leveson Inquiry. The Arab Spring has spread across the Middle East and North Africa, but after the toppling of dictators in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, civil war threatens to tear Syria apart. On the other side of the globe, the government of Burma (also known as Myanmar) is slowly moving to reform the country and only two weeks ago President Barack Obama made a historic visit to Rangoon. And finally, this August the Curiosity Rover landed on Mars. Although you can’t find Mars in our Atlas of the World (for obvious reasons), it captures the spirit of cartography: the exploration of the unknown and all that entails.

It was these four front-runners that we asked Oxford University Press employees to vote on and our Atlas committee to consider. Mars won the public vote, the OUP employee vote, and the hearts and minds of our Atlas committee.

Once we made our final decision on November 19th, we began contacting experts on Mars from around Oxford University Press to illuminate different aspects of the red planet. Inevitably, the first response we received asked us whether we had heard about the rumours surrounding NASA’s upcoming announcement. We took that as a good sign — and we’ll bring up An Atlas of Mars at our next editorial meeting.

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: US, china, Current Affairs, chinese, oil, Asia, burma, myanmar, *Featured, yunnan, Law & Politics, Business & Economics, david steinberg, straits, sein, Add a tag

It all began in November of 2010 when the military regime decided to release opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi who, since 1989, had been on house arrest under charges of attempting to divide the military. A few months later in the March of 2011, former Prime Minister and military hero Thein Sein was sworn in as President of the rapidly changing government. Among the numerous bold moves President Sein has made since assuming his new role in the fragile nation, arguably the most shocking has been the discontinuation of the controversial $3.6 billion Myitsone dam, a project funded by eager Chinese investors to generate electricity for millions of Chinese. What’s more, the West, most notably the United States, has seen this move by President Sein as a clear sign that his countries relations with the Chinese are turning sour. This is one of the reasons the Americans recently sent Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, the first American official to visit the country in fifty years, to speak with President Sein about a host of issues ranging from the severing of ties with North Korea to prolonged relief on economic sanctions girding the people of Burma. As America embarks on a new season of brinkmanship with the Burmese government, it is eminently important to understand the reasons why we are now so eager to embrace the new government while also studying the global implications of Burma turning a shoulder to their neighbors from the East, the Chinese.

Below is an excerpt from author David Steinberg’s book, Burma/Myanmar: What Everyone Needs to Know. Here, Steinberg details the economic and strategic interests China desires in Burma. – Nick, OUP USA

Although we can only speculate on Chinese motivation for the close relationship with the Myanmar authorities, strategic and economic issues seem paramount. Chinese influence in Myanmar is potentially helpful in any rivalry that might again develop with India, although Sino-Indian relations now are quite cordial. As China expands its regional influence and develops a blue-water navy, Myanmar provides access to the Bay of Bengal and supplements other available port facilities for the Chinese in the Indian Ocean in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka – called a “string of [Chinese] pearls.” Although the southern reaches of Myanmar are at the extreme western end of the Straits of Malacca, the free use of these straits are critical strategic concerns to China, Japan, Korea, and the United States. Some Chinese sources consider continued access to the straits to be a critical policy objective, and a close relationship with Myanmar is a potential advantage. Eighty percent of imported Chinese oil passes through these straits. To the extent that pipelines for oil and gas cross Myanmar and relieve Chinese dependence on the vulnerable Straits of Malacca, this is clearly in China’s strategic interests.

Access to energy sources is both a strategic and economic concern. Diversification of the supply of oil, natural gas, and hydroelectric power is an issue in which Myanmar looms large. The exploitation of offshore natural gas fields in Myanmar is important, as is the ability to transport that gas, as well as Middle Eastern crude oil, to China avoiding the Straits of Malacca, which is a strategic plus for China. China is helping construct some thirty dams, most of which will supply electricity to Yunnan Province as well as power and irrigation water to parts of Myanmar.

Under the SLORC/SPDC,

Blog: DRAWN! (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Drawn & Quarterly, Burma, Guy Delisle, travelogue comics, Add a tag

I’m currently reading Guy Delisle’s Burma Chronicles. He has supplemental photos and some samples of Burmese cartoonists on his site.

Blog: The Children's War (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Family, YA Fiction, Friendship, Burma, POWs, Add a tag

Elephant Run is an exciting action-packed story, set in 1941/2 in Burma (now Myanmar) just as Japan is turning its sites on it for military purposes.

Nick Freestone, 14, has been living with his mother and step dad in London, but now it is 1941, the Blitz is in full swing and one night, the building they are living in is destroyed by a bomb. His parents have become increasingly involved in wartime activities and Nick’s mother decides to send him to Burma, to live on his father’s timber plantation, Hawk’s Nest, and, she believes, in relative safety.

But safety really did prove to be only relative, since there is some tension in Burma because many of the Burmese want their independence from Britain. This sentiment is also shared by some of the mahouts, the men who work and care for the timber elephants on the Freestone plantation. After the Japanese have successfully invaded Rangoon, Burma’s capital, with the help of some of the mahouts, they also take over Hawk’s Nest, turning it into a military center of operations. Nick’s father is arrested and sent to a POW camp; Nick is held prisoner at the plantation and forced to work in what is now the garden of the cruel Colonel Nagayoshi. Nick’s work is supervised by the kinder Captain Sonji, but he is also at the mercy with the pitiless, vengeful Bukong, a former mahout who seems to enjoy beating Nick and others with his cane.

The one person who has real freedom of movement is Hilltop, a Buddhist monk who seems to be able to speak with the elephants and who is said to be over 100 years old. Hilltop knows the Burmese jungles better that anyone and offers Nick his one hope of escaping and rescuing his father.

Elephants are one of my favorite animals and I was very interested in that part of this book. Smith’s mahouts are very kind to their animals and seem to genuinely appreciate what they are capable of doing. One elephant in particular stands out in this book, a character in his own right, a example of the old adage that elephants never forget. Hannibal is a very large elephant who was once savagely attacked by a tiger while tied up. Not longer able to be used as a timber elephant, he roams the jungle. But as the story unfolds, the reader learns the role various people played in Hannibal’s life that demonstrates the truth in that adage.

Elephant Run is an ideal book for anyone who likes a well written, well researched book of historical fiction. It seamlessly incorporates the cultural history of mahouts and their elephants with the factual history of the Japanese invasion of Burma. In this story, the invasion centers on building a fictional airfield at Hawk’s Nest and using POWs, both foreign and Burmese, to build the very real Burma Railroad. This was an undertaking that resulted in a very high death rate among the workers, a fact Smith continuously points out. Because Nick is not familiar with life on his father’s plantation, Smith uses it as an opportunity to talk about the work of the mahouts, how the elephants are trained and other aspects of plantation life in Burma to inform the reader without straying from the story. Some might find this pedantic, I found it interesting.

This book is recommended for readers age 12 and up.

This book was purchased for my personal library.

There are excellent curriculum aides for Elephant Run are available at the author’

Blog: PaperTigers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Global Reads, Mitali Perkins, Eventful World, book discussions, online book group, Burma, Primary Source, online reading group, 1000th post, Bamboo People, Spirit of PaperTigers Book Set, Cultures and Countries, Add a tag

Having just finished reading Bamboo People, I was excited to see this email in my inbox today from Primary Source, a non-profit organization that promotes history and humanities education by connecting educators to people and cultures throughout the world:

Global Read of Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins

You are invited to join us for a discussion of the young adult novel, Bamboo People, by Mitali Perkins — a

compelling coming-of-age story about child soldiers in modern Burma. The online discussion forum will begin tomorrow – Wednesday, January 12th. Then join the author for a live chat on January 19th.

Online discussion forum: January 12th-19th, 2011

Live chat session with the author: Wednesday, January 19, 3:00 p.m. – 4:00 p.m. ESTRegister online here (registration is free but participants are responsible for obtaining their own copy of the book). All are welcome – teachers, students, parents, and anyone interested in global issues!

I’m off to register now and hope that some of our PaperTigers readers will join me!

P.S. Don’t forget to take a look at our 1,000th post, with the chance of winning a Spirit of PaperTigers 2010 book set. The deadline for entries is midnight Pacific Standard Time, on Wednesday 19 January with the draw taking placing in San Francisco on Thursday 20 January.

Blog: Book Dads (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: burma, book dads, child soldiers, myanmar, bamboo people, dads reading, YA - Fiction, mitali perkins, ya lit, Add a tag

Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins

Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins

Reviewed by: Chris Singer

About the author:

Mitali Perkins (mitaliperkins.com) was born in India and immigrated to the States with her parents and two sisters when she was seven. Bengali-style, their names rhyme: Sonali means “gold,” Rupali means “silver,” and “Mitali” means “friendly.” Mitali had to live up to her name because her family moved so much — she’s lived in India, Ghana, Cameroon, England, New York, Mexico, California, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Massachusetts.

Mitali studied political science at Stanford University and Public Policy at U.C. Berkeley before deciding to try and change the world by writing stories for young readers. Now she’s settled in Newton, a town just outside of Boston, where she writes full-time.

About the book:

Chiko isn’t a fighter by nature. He’s a book-loving Burmese boy whose father, a doctor, is in prison for resisting the government. Tu Reh, on the other hand, wants to fight for freedom after watching Burmese soldiers destroy his Karenni family’s home and bamboo fields. Timidity becomes courage and anger becomes compassion as each boy is changed by unlikely friendships formed under extreme circumstances.

This coming-of-age novel takes place against the political and military backdrop of modern-day Burma. Narrated by two fifteen-year-old boys on opposing sides of the conflict between the Burmese government and the Karenni, one of the many ethnic minorities in Burma, Bamboo People explores the nature of violence, power, and prejudice.

My take on the book:

In reading Bamboo People, this was my introduction to the works of Mitali Perkins. I was interested in reviewing this book due to my own personal experience several years ago teaching independent living skills to Burmese refugee youth. Almost all of the youth I met were either former child soldiers or had been orphaned due to the conflict in their country.

With that in mind, I found Ms. Perkins’ book to be a fascinating opportunity for readers to enter a world, occupied by youth similar in age to themselves, but characterized by horrible conflict and fear. The two main characters (Chiko and Tu Reh) are youth from opposing sides of the Burmese conflict. Chiko’s father was imprisoned as an “enemy of the state” for reading books. Chiko’s family is desperate for money so he answers a newspaper ad requesting teachers. The ad is a ruse however and he gets captured and conscripted into the army. Tu Reh is a Karenni refugee who lost his home and village to Burmese soldiers. He is understandably driven to enter the conflict by revenge but the words of his wise father keep him guessing his own intentions. Both main characters have their own internal conflicts, some typical of adolescent youth the world over, which will make them quite relatable for young readers.

Both characters eventually meet up under extraordinary circumstances. As the story comes to its c

Blog: PaperTigers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Mitali Perkins, Eventful World, Anne Sibley O'Brien, Burma, Mitali's Fire Escape, Rickshaw Girl, Jamie Hogan, PaperTigers Themes, Cultures and Countries, children's books about refugees, Add a tag

Following up on my post from last week, Mitali has graciously allowed us to share her blog post about the event here:

A thousand thanks to Porter Square Books in Cambridge, Ma and to my publisher Charlesbridge for hosting my Bamboo People book launch party. I always get nervous, so I greatly appreciated everybody who came and sent notes of encouragement from near and far. I’ve posted a few videos below, and here are some recaps from others who attended:

Charlesbridge, Walk the Ridgepole, Not Just For Kids, Britt Leigh’s Brain on Books, and The Papa Post

Arrived to find this gorgeous bamboo plant sent from Portland, Maine by Curious City’s Kirsten Cappy, Jamie Hogan (who illustrated my book Rickshaw Girl), Annie Sibley O’ Brien (After Gandhi), and King middle school librarian Kelley McDaniel. Thank you so much, ladies, for your love and support!I loved watching people mingle and meet.

My buddy Deb Sloan is one of the best book cheerleaders on the planet.

Authors who write for adults don’t get love like this.

Add a Comment

0 Comments on Mitali Perkins’ Bamboo People Book Launch Party as of 1/1/1900

Blog: Kids Lit (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Burma, Book Reviews, war, Middle School, Teen, Add a tag

Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins

Set in modern Burma, this novel is the story of two teen boys on opposite sides of the conflict between the Burmese and the Karenni, one of Burma’s ethnic minorities. Chiko’s father has been arrested for opposing the Burmese government. Now Chiko and his mother have no money to survive on, so Chiko heads out to be tested for a teaching position. But the test was a trap, and Chiko is taken into the Burmese army training to become a soldier. There he uses his wits to survive, befriending a street boy, who knows much more about fighting and survival than he does. When the time comes to allow his friend to head to the jungle on a dangerous mission, Chiko steps up and offers himself instead. Through that mission, he is rescued by Tu Reh, a Karenni teen, who has hated the Burmese ever since they burned down his village. Now Chiko’s life is in the hands of Tu Reh, who sees him only as the enemy. This book is about the bravery it takes to make decisions that turn boys into men, learning that compassion is the only way forward.

Beautifully written, Perkins has captured a complicated situation in a way that young readers will not only understand but will be drawn to. Rather than using alternating chapters for the two points of view, Perkins tells the first part of the book from Chiko’s point of view and then Tu Reh enters in the second half. This lends a great cohesiveness to the story, allowing readers to view the conflict from both sides, understand both, and at the same time get enough in-depth time with each character to see through their eyes.

Perkins excels at depicting foreign cultures through sounds, scents, and tastes. Food is used to convey the differences and similarities of cultures. There are no long paragraphs of description here, instead readers are treated to details woven into the story that bring the entire book to life. This is done with a skill that makes it seem effortless.

Her characterizations are also done with the same grace, allowing readers to slowly learn about the two boys, learn about the cultures, and slowly be exposed to the horror that teens on both sides of the conflict live with. The darker parts of battle and imprisonment are dealt with obliquely, allowing readers to bring their own level of understanding to the atrocities being committed. Again, this is a testimony to the skill of Perkins’ writing.

Highly recommended, this book takes the horrors of war and package them in a piercingly beautiful story. Appropriate for ages 12-15.

Reviewed from copy received from Charlesbridge.

Also reviewed by many, many other bloggers. Check out a list of them on Mitali’s blog.

Add a CommentBlog: DRAWN! (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Comics, Blogs, jerusalem, burma, guy delisle, traveller, Add a tag

Guy Delisle, traveller, animator, comic book artist, and author of the graphic novel, Burma Chronicles - is now blogging from Jerusalem where his wife is stationed with Doctors Without Borders.

Beautiful sketches and fun comics. I suspect a book will come out of this…

Blog: PaperTigers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Burma, The God of Animals, Gary Paulsen, Julia Alvarez, Iran, A Authors, In the Time of the Butterflies, National Reading Group Month, K Authors, C Authors, P Authors, S Authors, T Authors, Aryn Kyle, From the Land of Green Ghosts, Pascal Khoo Thwe, Ricochet River, Robin Cody, Winterdance, Dominican Republic, Mirabal sisters, online reading group, Oregon, Alaska, Wyoming, Kiriyama Prize, Iditarod, Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi, Add a tag

Although the Tiger’s Choice, the PaperTigers’ online reading group, selects books that are written for children but can be enjoyed by adults as well, National Reading Group Month has brought to mind those books written for adults that younger readers might adopt as their own favorites, and that could launch impassioned discussions between parents and children, teachers and students, or older and younger siblings.

The books on this week’s list are books recommended for teenagers, with content that may be beyond the emotional grasp of pre-adolescents. All of them are available in paperback and in libraries.

1) Ricochet River by Robin Cody (Stuck in a small Oregon town, two teenagers find their world becomes larger and more complex when they become friends with Jesse, a Native American high school sports star.)

2) The God of Animals by Aryn Kyle (Alice is twelve, growing up on a modern-day Wyoming ranch with a mother who rarely leaves her bed, a father who is haunted by the memory of Alice’s rebellious and gifted older sister who ran off with a rodeo rider, and an overly active imagination.)

3) Winterdance: The Fine Madness of Running the Iditarod by Gary Paulsen (The author of Hatchet tells the true story of how he raced a team of huskies across more than 1000 miles of Arctic Alaska in what Alaskans call The Last Great Race.)

4) Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (This autobiography of a young girl growing up in revolutionary Iran and told in the form of a graphic novel is rich, original, and unforgettable.)

5) From the Land of Green Ghosts by Pascal Khoo Thwe (An amazing odyssey of a boy from the jungles of Burma who became a political exile and a Cambridge scholar, this Kiriyama Prize winner is a novelistic account of a life filled with adventures and extraordinary accomplishments.)

6) In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez (The Mirabal sisters were beautiful, gifted, and valiant women who were murdered by the Dominican Republic government that they were committed to overthrow. Their true story is given gripping and moving life by their compatriot, Julia Alvarez.)

As the weather becomes colder and the days grow shorter, find your favorite teenager, choose a book, and plunge into the grand adventure of reading and sharing!

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Food and Drink, Geography, A-Featured, maps, keene, ben, mango, Ben's Place of the Week, atlas, ben keene, burma, chin hills, chin, hills, taxman, mangos, cashew, pinpointing, Add a tag

Chin Hills, Burma

Coordinates: 22 30 N 93 30 E

Maximum elevation: 10,018 feet (3,053 m)

Desperately trying to keep the Taxman at bay for a few more hours, I wound up at my favorite Monday night watering hole with a few friends last night, earnestly discussing the summer foods we enjoyed most. After listening to everyone’s peculiar arguments I found myself championing the mango as the perfect fruit for warmer days ahead. And yet as I tried to explain its versatility as an ingredient and its unrivaled popularity (the National Mango Board claims that more fresh mangos are eaten every day than any other fruit in the world), I realized that I knew precious little about its geographical origins.

As it turns out, this succulent relative of the cashew and the pistachio has been consumed in India for thousands of years, although it didn’t reach the United States until the late nineteenth century. Pinpointing the location of the first mango, when there are hundreds of varieties of the plant today, is not something I wanted to undertake but fortunately others had already agreed on the higher terrain forming the border between India and Burma (Myanmar). Running north-south, the evergreen-clad Chin Hills stretch across much of this tropical zone, and may hide an ancient progenitor in their forested slopes.

Ben Keene is the editor of Oxford Atlas of the World. Check out some of his previous places of the week.

Blog: Free Range Librarian (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, journals, Hot Tech, naked emperors, Add a tag

Thing is, sometimes I think we don’t know what business we’re in.

A couple weeks ago, while I was in the cornfields discussing library software, the National Book Critics Circle had a panel discussion in

It’s seventh-grade English all over again to observe that form is content, but apparently it’s a point worth repeating.

As I have noted before, full-text databases are marvelous, even indispensable research tools, but they are not an acceptable substitute for print literary journals. Online databases generally suck in some but never everything in a journal, and they extrude its content in half-right, disembodied, grossly fleckerized electronic format, ignoring the journal’s integrity of place (each journal issue has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and everything in that issue is there for a reason) and time (an issue is an ensemble performance, with a cast of poems, essays, short stories, reviews, and artwork that appear all at once; the journal’s serial nature is part of its whatness).

For a print literary journal, that integrity is key. I’m intimate with that integrity. I was a serial junky from childhood, when nothing made me happier than a fresh stack of Highlights and Consumer Reports, and for years I have read more serials than monographs—um, in Muggle-speak, I read more journals than books.

So I know that an issue of a journal is its own special experience, from its cover to its fonts to the arrangement of its pieces, with the editors’ loving attention to pull quotes, widow lines, and the like. The audiences for these journals—writers, readers, readers who want to be writers, professors, lecturers, and all fellow travelers—seek and even crave the formalism of the genre, perhaps because in a world that at times feels disembodied and fleckerized even when we are fully in it, the corporeal trueness of a journal is comforting.

A librarian first and foremost understands appropriate formats. Print is print, and digital is digital. To take a print object and make a digital copy is to create a surrogate object of the original, not to duplicate it with fidelity. As noted in my post on Critical Mass, you can’t replace the statue on the campus green with a microfiche of the statue; it’s not the same.

The surrogate copy may have its purposes; in some cases it may wildly improve on the original (as with some scientific content which is better off searchable); it may even be interesting in its own unexpected ways. But the original has meaning and purpose in itself, just as a slice of cake has meaning and purpose, and cannot be replaced by a picture of a cake and a food pill.

Writers (and some librarians) also know that journals also have a tremendous amount of incidental information. I have spent many hours researching advertising, photos, and notes in journals in order to recreate a time and a place, as I did for my essay “David, Just as he was” published this summer in White Crane. That incidental information is both part of the pleasure experience of a small literary journal and part of the stuff making up its whatness.

By small literary journal I mean both readership–Pleiades and The Missouri Review and Tin House are wonderful, but you won’t find them on most newsstands or for that matter in most public libraries—and, even more so, price. When Prufer asked why his library had stopped subscribing to journals, a librarian told him that funding was the issue. I’ve danced around the money issue before, but since librarians use that as a reason to stop subscriptions to literary journals, I need to tackle this head-on.

A comment to the blog post summarizing the NBCC panel discussion noted that science journal subscriptions can cost tens of thousands of dollars, and some academic libraries buy buckets and buckets and buckets of them. A Library Journal article from earlier this year demonstrates that average subscription costs for scientific journals are ten times the average cost of journals in the humanities (approximately $1000 to $100)—and that’s taking a very broad swath through the humanities, where some of the peer-reviewed titles extract more than their fair share of the budget, and not focusing on the literary journals.

Most literary journals run about $20 - $50 a pop per year–enough to give casual readers pause, as Stephen King recently observed, but far less than the titles that librarians are talking about when they say serials are expensive. A fairly comprehensive subscription to the Canon could be had for a couple thou a year, which is chump change against the scale of most academic serial budgets. I haven’t run the numbers, but I’m confident you could go hog wild and subscribe to everything on the newpages.com list of print literary mags and still spend less than you would for one of the top ten high-priced journals at Williams College.

God forbid I should ever suggest a university should deprive its scholars of access to a $25,000 journal on brain research, but it is worth observing that $25,000 could buy 568 subscriptions to ZZYZVA, or 694 subscriptions to The Sun, or 836 subscriptions to Tin House, or 1,041 subscriptions to The Missouri Review, or 1,136 subscriptions to White Crane. Plus—though admittedly I’ve never seen Brain Research—I’m guessing the artwork in the lit mags is prettier, and the poetry has to be for-sure better.

The panel in

It bothers me that we even need to make these points — and I worry that it’s just conference-panel-talk, where we all tsk, tsk and move along, move along.

Sometimes I think we librarians are so busy doing scholarly communication and gaming and blogging and getting NCIP to connect the hip-bone to the thigh-bone and on Dasher and Prancer and Donner and Vixen that we forget some basic stuff. Like how every issue of a journal has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and how the ink and paper smell when you crack the spine of a new issue and bury your face in the middle, and what it feels like to let your purse drop on the floor and slide into a chair and read Sascha Feinstein’s poem, “Shook Up,” and have that double shock of a good poem seeping into your mind as your eyes are feasting on the font, the order of words, and the faint orange margin lines on page 66 of the Spring, 2007 Missouri Review, so that even a lunk such as I, with my tragically unmusical ear, can almost grasp the beauty of this experience.

We think that if we can get a vendor to take parts of a thing, and jam those parts into a new format, and then stuff the sausage in a database, and link to it through our website, then our work on that boring subject is done, and we can go back to scheming about how we can get to the next fancy-schmancy conference to hear the same talks by the same pundits we heard at the last fancy-schmancy conference.

Because we have forgotten, if we ever knew, what it meant to slog across the lawn at the end of a long day and pull open the mailbox and have the sun come out shining all over our brain because there it was, the latest issue, with pages rough or smooth, deckled or razor-sharp, fragrant with fresh ink, just waiting for our touch.

And we have forgotten, if we ever knew, about the outlaw sensation of reading the best parts of a journal first, fanning the pages back and forth to shop, like running a finger across the back of a layer cake to get a heap of icing to lick while no one is looking. (Not that I have ever done either dastardly deed.)

Or perhaps we’re a little embarrassed by the topic, as if to advocate on behalf of something as humble as a $40 print literary journal read by that small rag-tag band wandering in from the English department meant we were low-tech and square. As if advocating for the statue on the green meant we were of a kind with the librarians who have mulishly resisted all good uses of technology, and our peers could now condescend to us for not “getting it.”

I do not exactly live on the Web, but I spend an unholy amount of time visiting its condos. So as a reader, a writer, and a true-blue digital librarian, I know I’m correct on this issue: ignore me or condescend to me, but when someone says a database is “just as good” as a print literary journal, I immediately see that emperor sashaying buck-naked down the street, his dangly bits swaying in the breeze.

Frankly, it irritates me, like a poppyseed caught in my bridgework, that I can’t get enough interest on this issue in LibraryLand.

Oh yeah, so true (yawn), too bad about that (yawn), tough about those journals, but I’m…

a) Running off to a conference on cataloging in Second Life

b) Working on my Farsi translation of Dance, Dance, Revolution

c) Drafting the NISO standard for Library 3.0

Then there was that sparkly young thing who said none of this mattered because We’re All Going Electronic Anyway, which is what I suspect everyone is thinking. Well, that takes care of that, then!

Yes, of course, we’re moving to a networked future. I read online literary journals (which, of course, are ignored by most commercial aggregators, since they aren’t a source of revenue). Hell, I even write for them. By gum, I’ve been known to blog.

But I’ve said it before about another, not-too-distant issue: as librarians, it’s not our job to engage in social engineering, and it is our business to advocate for our users; as that great librarian Marvin Scilken said thousands of times in his long career, the bottom line is service. If a community is best served by print literary journals–at least for now, and to a reader, now is what matters–then it’s our job to go to bat for them. That may mean pausing long enough to learn just what it is we’re delivering, but that’s our job, too.

Very good review Alex. Several WWII books I read mentioned the Burma invasion, but I think I'd probably learn more from this book.

http://www.ManOfLaBook.com