new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: arsenault, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: arsenault in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Lauren,

on 5/13/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

rides,

raymond,

anniston,

seigenthaler,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

sweet home alabama,

vanderbuilt,

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

nashville,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

college students,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 5–May 12: Anniston, AL, to Nashville, TN

Our fifth day on the road started with the dedication of two murals in Anniston, at the old Greyhound and Trailways stations. I worked with the local committee on the text, and I was pleased with the results. In the past, there was nothing to signify that anything historic had happened at these sites. The turnout of both blacks and whites was gratifying and perhaps a sign that Anniston has begun the healing process of confonting its dark past. The students seemed intrigued by the whole scene, including the media blitz. We then boarded the bus and traveled six miles to the site of the bus burning; we talked with the only local resident who was there in 1961 and with the designer of a proposed Freedom Rider park that will be built on the site, which now boasts only a small historic marker. I have mixed feelings about the park, but perhaps the plan will be refined to a less Disneyesque form. It was quite a scene at the site, but we eventually pulled ourselves away for the long drive to Nashville.

Our first stop in Nashville was the civil rights room of the public library, the holder of one of the nation’s great civil rights collections. Rip Patton gave a moving account of his life as a Nashville student activist. We then traveled across town to the John Seigenthaler First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, where John Seigenthaler talked with the students for a spellbinding hour. He focused on his experiences with the Kennedy brothers and his sense of the evolution of their civil rights consciousness. As always, he was captivating and gracious, and full of truth-telling wit. We gave the students the night off to experience the music scene in Nashville, while I and the Freedom Riders participated in a Q and A session following a screening of the PBS film. The theater was packed, and the response was very enthusiastic. It was great to see this in Nashville, a hallowed site essential to the Freedom Rider saga and the wider freedom struggle. On to Fisk this morning before journeying south to Birmingham and “sweet home Alabama.”

Raymond Arsenault is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History and and Director of Graduate Studies for the Florida Studies Program at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. You can watch his discussion with dire

By: Lauren,

on 5/12/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

Martin Luther King,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

KKK,

college students,

1961,

coretta scott,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

rides,

raymond,

anniston,

augusta,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 4–May 11: Augusta, GA, to Anniston, AL

As we left Augusta, I gave a brief lecture on Augusta’s cultural, political, and racial history–emphasizing several of the region’s most colorful and infamous characters, notably Tom Watson and J. B. Stoner. Then we settled in for the long bus ride from Augusta to Atlanta, a journey that the students soon turned into a musical and creative extravaganza featuring new renditions of freedom songs, original rap songs, a poetry slam–all dedicated to the original Freedom Riders. These kids are quite remarkable.

In Atlanta, our first stop was the King Center, where we were met by Freedom Riders Bernard Lafayette and Charles Person. Bernard gave a fascinating impromptu lecture on the history of the Center and his experiences working with Coretta King. We spent a few minutes at the grave sight and reflecting pool before entering the newly restored Ebenezer Baptist Church. The church was hauntingly beautiful, especially so as we listened to a tape of an MLK sermon and a following hymn. The kids were riveted.

Our next stop was Morehouse College, King’s alma mater, where we were greeted by a large crowd organized by the Georgia Humanities Council. After lunch and my brief keynote address, the gathering, which included 10 Freedom Riders, broke into small groups for hour-long discussions relating the Freedom Rides to contemporary issues. Moving testimonials and a long standing ovation for the Riders punctuated the event. Later in the afternoon, we headed for Alabama and Anniston, taking the old highway, Route 78, just as the CORE Freedom Riders had on Mother’s Day morning, May 14, in 1961. However, unlike 1961’s brutal events, our reception in Anniston, orchestrated by a downown redevelopment group known as the Spirit of Anniston, could not have been more cordial. A large interracial group that included the mayor, city council members, and a black state representative joined us for dinner before accompanying us to the Anniston Public Library for a program highlighted by the viewing of a photography exhibit, “Courage Under Fire.” The May 14, 1961 photographs of Joe Postiglione were searing, and their public display marks a new departure in Anniston, a community that until recently seemed determined to bury the uglier aspects of its past. The whole scene at the library was deeply emotional, almost surreal at times. The climax was a confessional speech b

By: Lauren,

on 5/11/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

oprah,

violence,

charlotte,

1961,

Raymond Arsenault,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

documentary,

college students,

riders,

lunch counter,

rides,

raymond,

Freedom Riders,

freedom rides,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 3–May 10: Charlotte, NC, to Augusta, GA

We started the day with a breakfast meeting at a black Pentecostal church in West Charlotte. The students had the chance to sit with local civil rights activists such as former Freedom Rider Charles Jones, who gave another inspirational “blessing” that included rousing freedom songs. The next stop, a few blocks away, was West Charlotte High School, an important site in the school desegregation saga in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County. Since our freedom bus was temporarily out of commission (the AC was being fixed), we drove up in a red, doubled-decker, London-style “party bus.” Some of the kids rushed out to greet us, perplexing the school security guards, who weren’t expecting a freedom ride on their doorstep. West Charlotte High, once a model of racial integration and educational improvement, has fallen on hard times, the victim of resegregation and neglect since the mid-1990s.

On to Rock Hill, SC, the birthplace of “jail-no bail” in February 1961 and the home of the courageous Friendship Nine, arrested in 1961. Five of the nine joined us for an emotional lunch at a recently refurbished McCrory’s, site of the famous 1961 sit-in. Andrea Barnett, a black special-ed teacher from Charlotte, who recently completed a 3,000 mile Freedom Ride (designed to instill self-confidence in her students) on her motorcycle, accompanied by her white boyfriend, from DC to New Orleans and back to Charlotte, was on hand to sing a beautiful and moving folk song (that she wrote) dedicated to the Freedom Riders. Also on hand was a Catholic priest, Father Boone, who has been in Rock Hill for 52 years, much of the time a lone local white voice preaching racial tolerance and justice. It was quite a scene. As we drove off across South Carolina to Augusta, GA, there were more than a few tear-stained faces on the (mercifully) retooled, air-cooled freedom bus. On to Atlanta and Anniston this morning.

Raymond Arsenault is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History and and Director of Graduate Studies for the Florida Studies Program at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. You can watch his discussion with director Stanley Nelson on The Oprah Show

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

greensboro,

college students,

1961,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

lunch counter,

lynchburg,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 1-May 8: Washington to Lynchburg,VA

Glorious first day. Student riders are a marvel–bright and engaged. Began with group photo in front of old Greyhound station in DC, where the 1961 Freedom Ride originated. On to Fredericksburg and a warm welcome at the University of Mary Washington, where James Farmer spent his last 14 years. One of the student riders, Charles Lee is a UMW student. Second stop at Virginia Union in Richmond, where the 1961 Riders spent their first night. Greeted by VU Freedom Rider Reginald Green, charming man who as a young man sang doo-wop with his good friend Marvin Gaye. Third stop in Petersburg, where former Freedom Rider Dion Diamond and Petersburg native led a walking tour of a town suffering from urban blight; drove by Bethany Baptist, where the 1961 Riders held their first mass meeting. On to Farmville and the Robert Russa Moton Museum, formerly Moton High School, the site of the famous 1951 black student strike led by Barbara Johns; our student riders were spellbound by a panel discussion featuring 2 of the students involved in the 1951 strike and later in the struggle against Massive Resistance in Farmville and Prince Edward County, where white supremacist leaders closed the public schools from 1959 to 1964. On to Lynchburg, where the 1961 Freedom Riders spent their third night on the road and where we ended a long but fascinating first day. Heade for Danville, Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte this morning. Buses are a rollin’!!!

Day 2-May 9: Lynchburg, VA, to Charlotte, NC

The second day of the Student Freedom Ride was full of surprises. We left Lynchburg early in the morning bound for Charlotte. We passed through Danville, once a major site of civil rights protests, where the 1961 Freedom Riders encountered their first opposition and experienced their first small victory–convincing a white station manager to relent and let three white Riders eat a “colored only” lunch counter.

Our first stop was in Greensboro, where we toured the new International Civil Rights museum, located in the famous Woolworth’s–site of the February 1, 1960 sit-in. This was my first visit to the museum, even though I was one of the historical consul

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

Audio & Podcasts,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

Add a tag

This article and audio component was produced by Adam Phillips of Voice of America.

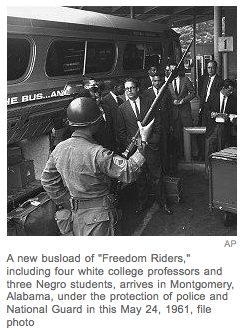

The American South was a segregated society 50 years ago. In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation in restaurants and bus terminals serving interstate travel, but African-Americans who tried to sit in the “whites only” section risked injury or even death at the hands of white mobs. In May of 1961, groups of black and white civil rights activists set out together to change all that.

[See post to listen to audio]

They called themselves “Freedom Riders.” An integrated group of young civil rights activists decided to confront the racist practices in the Deep South, by travelling together by bus from Washington D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana. Raymond Arsenault documents their trip in “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” He says many elder civil rights leaders denounced their strategy as a dangerous provocation that would set back the cause.

“But the members of the Congress of Racial Equality that came up with this idea, the young activists, were absolutely determined that they were going to force the issue, that they had to fight for ‘freedom now,’ not ‘freedom later,’ [and] that someone had to take the struggle out of the courtroom and into the streets, even if it meant for death for some of them. They were willing to die to make this point,” said Arsenault.

The group boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington on May 4. They planned to stop and organize others along the way until they reached their destination on May 17. Like Martin Luther King, Jr. and other prominent civil rights activists of the day, the Freedom Riders were trained in the techniques of non-violent direct action developed by the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Arsenault says that for some of them, non-violence was a deeply held philosophy. For others, it was a tactic to win public support for their struggle.

The group boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington on May 4. They planned to stop and organize others along the way until they reached their destination on May 17. Like Martin Luther King, Jr. and other prominent civil rights activists of the day, the Freedom Riders were trained in the techniques of non-violent direct action developed by the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Arsenault says that for some of them, non-violence was a deeply held philosophy. For others, it was a tactic to win public support for their struggle.

“Part of what they did was they dressed very well, almost like they were going to church and they were absolutely committed to not striking back and being polite, and to contrast their behavior with what they saw as the white thugs who might very well attack them, and of course did,” added Arsenault.

The Freedom Riders were taunted – and attacked – throughout the South. John Lewis, now a U.S. Congressman, was badly beaten in South Carolina. Worse trouble awaited the Freedom Riders in Birmingham, Alabama, where white supremacists beat the Riders with clubs and chains while police looked on. In Anniston, Alabama, a mob surrounded the bus, slashed its tires, and firebombed it on a lone stretch of highway outside of town.

In interviews culled from “Freedom Riders“, a new PBS documentary tied to Arsenault’s book, several of the Riders recall how they narrowly escaped death.

“I can’t tell you if I walked off if I walked off the bus or crawled off, or someone pulled me off,” said one woman.

“When I got off the bus, a man came up to me, and I am coughing and strangling and he said ‘Boy, are you alright?’ And I nodded, and the next thing I knew I was on the ground. He had hit me with a baseball bat,