Chess is not the oldest game of humankind. That honor goes to an Egyptian board game dating back to 3500– 4000 BC. But chess’s longevity is remarkable. While claims of the true beginnings of chess are various and the origins are shrouded in mystery, consensus exists that the game as we recognize it began on the Indian subcontinent in approximately 700 AD, although Persia shaped the early game as well. As with so many origin stories, one can find political motives. For instance, some claim that chess originated in Uzbekistan or even in China.

Chess is considered a war game, or at least a game that models warfare or prepares soldiers, although some legendary origins (Myanmar or Sri Lanka) suggest in a more pacifist fashion that the game was developed to provide a less bloody equivalent to conflict. Given the passion of Napoleon for the game, such sublimation was not inevitably effective. When the game spread to the Islamic world, which rejected gambling and gaming, chess was permitted because it was considered preparation for war. In the Soviet Union, the game was treated not as a bourgeois diversion but a form of proletariat culture.

Over the years, the rules of chess evolved. By the Middle Ages, chess had gained admirers in Europe. Its popularity is evident in writings about chess as morality by Pope Innocent III and Rabbi ben Ezra, both around 1200 AD.9 The second book printed in English, The Game and Playe of the Chesse (translated from the French), addressed chess as morality. The medieval attention to chess is evident in that the names and movement of the chess pieces changed substantially during this period. The most salient change was to increase the power of the vizier, making it the most powerful piece on the board. This transformation, first labeling the piece the queen and then increasing her range, occurred between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Some suggest that this change reflects the authority of women in medieval and Renaissance Europe. Perhaps these explanations are shaped by scholarly wishful thinking, but it is clear that chess changed substantially during the late Middle Ages, and as a result, games prior to the introduction of the powerful queen are rarely studied. Although chess has continued to evolve, a game played after the introduction of the powerful queen is essentially the same game that we play today. The first international tournament was organized in 1851, and by 1886 the world had its first undisputed chess champion, Wilhelm Steinitz.

Depending on one’s definition, today there are many chess players or a great many. A large proportion of Americans, although surely nowhere close to a majority, can play chess at some level. According to Susan Polgar, a prominent grandmaster, there are forty-five million chess players in the United States. Other estimates are slightly lower, but most hover around forty million. In chess hot spots such as Russia, eastern Europe, Iceland, Cuba, and Argentina, the proportion is far higher. Polgar guesses that there are seven hundred million players worldwide. Some skepticism of that figure is warranted, but chess is indeed a global game.

We must distinguish between those who are knowledgeable about the basic rules and those who have a commitment to the game: those who play chess and those who participate in the chessworld. Here the numbers diminish. Though we do not have firm figures for the number of serious players, as of 2010 the United States Chess Federation (USCF) had a membership of approximately eighty thousand. Some of these members are not active, and many others play chess outside the auspices of the organization (particularly in scholastic chess, where some state and city organizations run their own tournaments). The USCF claims that there are approximately ninety thousand active tournament players. In the last fifteen years, there has been substantial growth in the number of young (scholastic) chess players. Chess is now treated as an activity that provides cultural capital. Playing the game is said to increase a child’s cognitive development. In an age in which many parents wish to cultivate their children, chess is treated as a valued training ground, even if it is not perceived as one of those life skills that will continue into adulthood. Estimates of the number of children playing chess run as high as thirty million. But whatever the number, it is striking that the largest number of members of the USCF are third and fourth graders. According to one source, 60 percent of the members of the USCF are age fourteen or younger. While the politics of the organization are set by adult members (one must be sixteen to vote in federation elections), many of the organizational resources are contributed by scholastic members. As a result, it is not surprising that battles have been fought over whether to use resources for high-visibility adult chess or the more popular scholastic chess. Some scholastic chess tournaments are profitable, and the growth of youth chess provides employment for adult teachers.

On many demographic dimensions chess holds up well. A visit to a large tournament finds an impressive number of African Americans, South Asians, East Asians, Hispanics, and eastern European immigrants. A large tournament has the feel of a United Nations of leisure. Such diversity is rare in leisure or voluntary activities. While chess is largely a middle-class pastime, some participants hold working-class jobs or are from working-class homes. And many children participate at adult tournaments. It is common to find a nine-year-old playing— and crushing— a sixty-nine-year-old, an oft -remarked reality that leads to adults being reluctant to play children, who are often better than their ratings suggest. One tournament I attended had participants from five to eighty-seven, a range that was not especially remarkable. The only exception to this demographic diversity is gender. Chess has long been— and still is—male dominated, and the participation of women declines with age and with rated ability. In elementary school as many as 40 percent of players are girls, but there is only one woman in the top one hundred US chess players. In most domains, at least 90 percent of chess players are male, an even greater percentage than in Little League baseball, Dungeons & Dragons, or high school debate. Because of the highly gendered structure of chess and to avoid awkward syntax, I use the male pronoun. Perhaps before too long, readers will find my pronoun usage odd and inappropriate.

THE METAPHORS OF CHESS

When one examines any activity, an inevitable question emerges: what kind of thing is this? Put another way, what is the “cultural logic” of chess? What framework of meaning explains this community? What conventions are embraced? In what domain of activity do we place it? This is the human desire for labeling and categorization. Compared to other games, chess is incredibly deep. No two games are the same, and the seemingly unending choices have lured many players. Chess edges close to infinite possibility. The number of legal positions in chess has been estimated at 1040 (the number of stars in the universe is estimated at 1024), the number of possible games is 10120, and chess databases contain over 3.5 million games.

Is chess so multifaceted? Why and how do these figures resonate with chess players? In the diversity of metaphors, chess exemplifies generic features of human association, including focus and attention, affiliation, beauty, status, collective memory, consumption, and competition. These are topics to which I return.

Perhaps the most obvious metaphor, and hence the one that I address least, is that chess is a game, a form of voluntary activity, grounded on rules and on rivalrous competition. One might say that “game” is not a metaphor but a description. Its voluntarism links chess, like all games, to play, but games have a structured organization that “pure play” lacks. The model of human activity as game, a common metaphor, suggests a strategic approach to everyday life. Chess is a game of strategy and tactics. But it goes beyond the domain of the game, even if other activities (sex, business, or politics) can be treated as symbolic games because of their strategic dimensions.

While chess is a game—a minor aspect of life— it can be treated as much else. Metaphors abound. In a riot of metaphors, Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg argue that the game takes many forms, depending on style. Chess can be a fight, an art, a sport, a life, or a war. Folklorists Marci Reaven and Steve Zeitlin, touring public chess spaces in New York City, found competing visions of chess: an unsolved mathematic problem, a language, a search for truth, a dream, and even “a ball of yarn.” Some speak of chess as a race and the chessboard as a piano. The personification of pieces is common, particularly in scholastic chess. Pawns desire friends, pieces are runners, they look for a job or are unhappy and crying (field notes). The range of cultural images that define this pastime is extensive. Such diversity suggests that activities do not have a singular meaning but can be framed in multiple ways to connect with the needs of the speaker and desires of the audience.

Treating chess as a game of war 23 leads to military metaphors. In one account, the rook is a panzer unit, the knight a spy, the bishop a reconnaissance officer. As the population of chess players is overwhelmingly male, violent and sexual metaphors are common, as when the defeated are judged as weak, soft, or effeminate. Opponents are pinned, hit, stomped, crushed, sacked, or killed. More explicit is the claim of world champion Alexander Alekhine that during a match “a chess master should be a combination of a beast of prey and a monk.” While not many chess players speak so graphically, grandmaster Nigel Short was not alone when he remarked, “I want to rape and mate [my opponent].” In his rant, Short provides support for a Freudian analysis of chess as a sublimated form of homosexual eros and parricide.

Freudians believe that the unconscious appeal of chess results from oedipal dynamics, leading to sexual and aggressive themes. Reuben Fine pondered why many strong chess players display psychiatric disorders, seeing danger in the metaphorical dynamics of the game. Fine argued that chess is often learned by boys at puberty or earlier and that the pieces represent a symbolic keying of ego development (the king is a phallic symbol representing castration anxiety; the queen represents the mother). Those drawn to chess are said to have difficulty balancing aggressive and sexual impulses because of a weakly developed superego. Players are susceptible to developing neurotic traits, echoing grandmaster Viktor Korchnoi’s observation that “no Chess Grandmaster is normal; they only differ in the extent of their madness.” Others point to unconscious aggressive and sexual themes. Any competitive chess player knows the stories of madness, including those of Paul Morphy (“the pride and sorrow of chess”) and Bobby Fischer. However, these examples do not tell the whole story. Focusing on atypical cases such as Morphy’s or Fischer’s paranoia is an inadequate basis for generalization. Much psychoanalysis of chess is based on speculative Freudian assumptions with little empirical support; perhaps this is related to the fact that many psychoanalysts, notably Reuben Fine, are serious chess players. The evidence is more literary confection than systematic proof.

Besides these tendentious images, others build on morality or images of the state. The great Dutch historian of play, Johan Huizinga, argued that “civilization arises and unfolds in and as play.” His assertion applies to the vast array of political metaphors of chess. Chess reveals not only sexual and aggressive dynamics, but social order. Th is is one reason that authors select chess as a background (or foreground) for understanding human relations: Nabokov, Cervantes, Borges, Tolstoy, Ezra Pound, Edgar Allan Poe, and Woody Allen. As early as 1862, the well- known chess editor Willard Fiske, writing as B. K. Rook, connected pieces and society:

We [rooks] are generally considered as the most upright and straightforward of all the denizens of Chessland, from our habit of moving. . . . We have long been the fast friends of the Kings. . . . Of the Bishops there is little to relate. Each of the chess races possesses two individuals of this name, and yet so strong is the hatred of those belonging to the same stock that one of them can never be induced to go into a house that has been occupated by the other. . . . The most erratic members of our state are undoubtedly the Knights. . . . The Pawns are the most numerous members of our body politic.

Lewis Carroll’s imaginings in Through the Looking-Glass have something of the same flavor. The twelfth-century Persian poet Omar Khayyam proclaimed, “We are in truth but pieces on this chess board of life.” To Pope Innocent III (1161– 1216), a chess player himself, was attributed a morality on chess (now thought to be written by John of Wales) that asserts, “This whole world is nearly like a Chess-board, one point of which is white, the other black, because of the double state of life and death, grace and sin. The familia of the Chess-board are like mankind; they all come out of one bag, and are placed in different stations.” Harry, a well-regarded teacher of my acquaintance, expressed the same theme: “The thing I love about chess is that at the beginning of the game, ever yone is equal. Everyone is a citizen, and then through the game, we see what they can do. Chess represents our democratic values. It provides a metaphor of society” (field notes). Pieces stand for political positions—whether democratic or monarchical—in a way easily recognized by children and adults.

As a result, chess is used metaphorically, by the public as well as players. Away from the chessboard, we speak metaphorically of a stalemate, selecting a gambit, or keeping an opponent in check. The political metaphors were even more extensive in medieval and Renaissance Europe. Jenny Adams emphasizes how the game extended politics, reflecting a medieval social hierarchy, sometimes considered an instrument of reform. The English playwright Thomas Middleton in his drama A Game at Chess satirized abortive marriage negotiations between Charles, the son of James I, and Donna Maria, the sister of Philip IV of Spain.

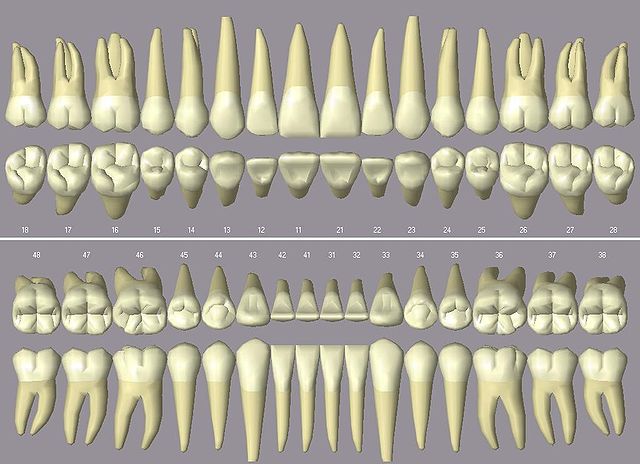

Nowhere is the sociopolitical culture of chess more evident than in the names of the pieces. Chess is a global game in which the pieces have had different meanings over time and in various languages. The names of chess pieces in English and other western European languages were changed from their Middle Eastern designations, as medieval society treated the game as a mirror. The vizier became a queen, the horse a knight, and the elephant a bishop. The allegories of chess were revised. In contrast, even today Russian mirrors the Arabic; there is no queen, but a “ferz,” a counselor. While Russian chess has a “king,” the word used for king is korol, not czar. Perhaps the most problematic example of political labeling is the bishop, borrowed from the Catholic hierarchy. In Russia and throughout much of Asia, the bishop is an “elephant” (borrowed from Indian tradition); in Hebrew and in Dutch the bishop is a “runner,” and in France, the bishop is the fou or “fool.” An account of the naming of chess pieces reveals much about the societies in which they are used. At moments of transition, as in the Middle Ages, names are “in play.” At the time of the American Revolution there was an attempt to rename king, queen, and pawn as governor, general, and pioneer. After their revolution Soviets wanted to use the name commissar and to turn black into red, with its pieces representing the proletariat. Such changes, however, could not overturn the inertia of collective knowledge. These fights over metaphors indicate how tightly linked chess is to the social structure of its location and how its location affects its image.

While some activities fall neatly into human categories— sculpture is art, chemistry is science, tennis is sport—chess can plausibly be seen as all three, each with its own conventions, like any established and collectively recognized social world. Conventions—norms of proper activity— are to be found in all institutionalized domains. Chess action can be striking, systematic, or strategic. The former world champion Anatoly Karpov claimed in an oft-quoted remark that “chess is everything— art, science, and sport.” Perhaps chess is not everything, but each of these categories has been treated as the primary basis of the game.

While some activities fall neatly into human categories—sculpture is art, chemistry is science, tennis is sport—chess can plausibly be seen as all three, each with its own conventions, like any established and collectively recognized social world. Conventions—norms of proper activity—are to be found in all institutionalized domains. Chess action can be striking, systematic, or strategic. The former world champion Anatoly Karpov claimed in an oft-quoted remark that “chess is everything— art, science, and sport.” Perhaps chess is not everything, but each of these categories has been treated as the primary basis of the game.

CHESS AS ART

The rhetoric of chess as constituting an art form is extensive. There are styles and schools of chess, and beautiful moves and combinations. World champion Emanuel Lasker asserted, “There is magic in the creative faculty such as great poets and philosophers conspicuously possess, and equally in the creative chessmaster.” The brilliant Ukrainian grandmaster David Bronstein wrote, “Chess is a fortunate art form. It does not live only in the minds of its witnesses. It is retained in the best games of masters, and does not disappear from memory when the masters leave the stage.” Discussions of symmetry and beauty are seen not only in the writings of masters but in descriptions by amateurs: “It’s kind of hard to see, but there’s beauty in it. The symmetry of the pieces and the idea of threatening, sometimes it all just comes together and it gets distracting at points, but sometimes I really just sit back and go ‘Wow, look at this game.’ It’s like a perfect balance, an absolutely perfect piece of art. . . for instance the idea of a checkmate that’s six moves away is just beautiful.” In simpler words, a high school player remarked, “I like chess because of the way it flows together and it’s like meticulous and artistic. And [my friend] said that’s why he liked music” (interview). I have heard players liken chess to improvisational jazz in the way that combinations of pieces emerge over the course of a game. The rhetoric of competition as art is hardly unique to chess. In examining lifestyle sports, such as surfing, skateboarding, or windsurfing, Belinda Wheaton points to activities linked to the participants’ sense of self. She notes a similar attention to artistic expression, stylistic nuance, and creative invention. For those in the upper echelon, chess also constitutes a lifestyle community, although one with less threat of injury than so-called extreme sports.

Much beauty is found in the elegance of a perfect and inescapable solution to a complex problem. As William James posited, solving problems is deeply gratifying and reveals aesthetic satisfaction. If beauty exists in a competitive environment, it cannot be an individual achievement but must be relational. The philosopher Stuart Rachels observes: “Great chess games are breathtaking works of art. . . . Perfect play, however, cannot guarantee a beautiful game. For one thing, it is not enough that you play perfectly; your opponent must also play well.” Another player writes, “It only takes one brilliant mind to conjure up a brilliancy, but it takes two minds . . . to produce the position in which the fireworks can be let off .” The challenge of a patzer does not produce beauty for the skilled player.

The specific metaphor used by chess players to describe a moment of artistry is brilliancy: a cut diamond on a square board. Brilliancy results from the awe experienced from a simple and perfect answer to a daunting and complex problem— a victory, but not only a victory. The concept is so central to the world of chess that many elite tournaments award a “brilliancy” prize for the game or position with the greatest aesthetic appeal. Brilliancies result from a novel combination of pieces that produces a position that colleagues find startling, even spiritual. Each piece supports and defends other pieces of that color while attacking the opponent’s pieces. As Reuben Fine remarked, “Combinations have always been the most intriguing aspect of Chess. The masters look for them, the public applauds them, the critics praise them. . . . They are the poetry of the game; they are to Chess what melody is to music.”

Often the brilliancy derives from the victor’s sacrificing or placing a piece in danger; only later do obser vers recognize that the stratagem led to victory. “The bigger the sacrifice, the more beautiful.” It is because of his willingness to sacrifice his queen that thirteen-year-old Bobby Fischer’s defeat of former United States Open champion Donald Byrne at the Rosenwald Memorial Tournament in New York is called “the game of the century.” The brilliancy was not recognized when the move was first made but only after the game was analyzed and revealed in time.

How is the beauty of chess experienced? How do players become engrossed in chess play? Part of the beauty of chess is its experienced quality. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi speaks of “flow” to capture the capacity of people to focus on an activity so closely that they lose awareness of time, external surroundings, and self-consciousness. Such experiences become autotelic, as the boundaries between self and activity fade. This is when we are most creative, productive, and satisfied in our work, leisure, and personal lives. Csikszentmihalyi selected chess as a key example of a focused activity. Players report performing best when the flow experience is maximized and they “dig in” to the game. It is not only the logic of pieces on the board that contributes to treating chess as art, but experienced emotions. Liquid moves replace concrete choices.

CHESS AS SCIENCE

Players commonly view chess as a science, and many of the greatest chess players (as well as those less gifted) have jobs in technical or scientific fields. Adolf Anderssen, Emanuel Lasker, and Max Euwe were mathematicians; Mikhail Botvinnik was an engineer, and José Raúl Capablanca also studied engineering. As one player explained, “They are all math guys.” Reuben Fine estimated that about half of the greatest players had mathematical or scientific backgrounds.

The metaphor of chess as science relies on the commonsense image of science as value-free, objective, and rigorous. In chess some assert that there is always one best move in a given position. For these players, worrying about “chess psychology” is wasted time if the proper move can be found through rational deliberation. As one informant explained, players review their games because “they are looking for the truth.” At any point there is only “one truth in the position” (field notes). For many players and some philosophers there is “truth in chess.” Computer programs such as Rybka or Fritz are popular in that they support this comforting illusion, no matter the action of an opponent. From this perspective one should play the board, not the opponent. Bobby Fischer was a leading exponent of this view, avowing, “I don’t believe in psychology. I believe in good moves.” His position has a powerful logic. The rhetoric of science proclaims that long-term strategies and short-term tactics can be developed through close study of the principles of chess. Aron Nimzowitsch’s Chess Praxis treats chess as a science by stressing fundamental principles, such as “centralization” and “over- protection.” Such a systematic presentation of chess theory emphasizes logic and objectivity, training the mind to apply general principles to vaguely defined situations. Chess is a game of perfect information, in which chance or information unequally distributed among the players should not play a role (as in poker or bridge), and this enshrines science. Each player has the opportunity to see the same things, even if background or training does not permit that seeing.

Chess theory has evolved over time in fits and starts. Of course, much theory cannot be easily detached from stylistic preferences or accepted conventions of play, tied to local chess cultures. Innovation is necessary for grandmasters to dethrone their predecessors; the tactical and strategic answers that worked in previous models are translated into an approach that is alleged to be objectively superior. As games are won and lost, newly “correct” and “objective” approaches to the game are discovered, and advice is reframed. This model suggests that chess theory is metaphorically likened to a science with experimental tests. However, as scholars of science studies indicate, a simple-truth model of scientific progress is not persuasive. Science advances through changes in practices that are defined as legitimate and embedded in social relations. The rational and objective basis of science cannot be separated from cultural context, politics, and scientific reputations and is often contested as chess styles rise and fall.

Max Euwe and John Nunn note that “succeeding generations of experts have contributed to the development of chess play, but it was the style of some outstanding individual which moulded the thinking and style of play of his time.” Perhaps this lays too much emphasis on the genius, rather than the community of competitors, but they rightly indicate the dynamics of change. This is what international master Anthony Saidy terms “the battle of chess ideas.”

Styles of play did not develop steadily and cumulatively but often advanced in revolutionary paradigm shifts that served as strategic replies to dominant paradigms. The objectivity of theoretical principles is often blurred by the confounding factor of creative genius and calculative ability found in the best players. Further, chess theory, like scientific knowledge generally, is in part “Whig history,” a theory of continual progress that interprets the past in light of the choices that characterize the activity in the present.

In the chessworld, as in science, knowledge is acquired socially. Advancement depends on challenges over the board. Players participate in local and extended networks of knowledge, but always based on the recognition of community. Chess is a set not just of ideas but of ideas that become recognized through social relations and shared practices.

CHESS AS SPORT

Chess games are competitive, like the world of sports. While the more prestigious images of chess as art or science are common, the agonistic aspects of sport are also evident. As the Great Soviet Encyclopedia suggests, chess is “a sport masquerading as an art.” Chess can be symbolically “bloody,” as pieces live and die. This reality thrills players, motivates improvement, and shapes status hierarchies. Many players attribute their love for chess to the cutthroat competition. Former world champion Anatoly Karpov remarked, “Chess is a cruel type of sport. In it the weight of victory and defeat lies on the shoulders of one man. . . . When you play well and lose, it’s terrible.” Indeed, checkmate is derived from the Persian for “the king is dead.” As a master-level player describes the hypercompetitive approach of top players at a local club, “The masters at the top . . . [are] very competitive, and [have] big egos. . . . Their whole attitude. . . [is] that I am going to crush you. And I will be extremely rude. And I will do whatever is necessary to crush you.” Another player explained to me, “Chess is like hand-to-hand combat. It’s so visceral. How can I hurt you?” (field notes). Such metaphors are so common as to be unremarkable.

Why is chess so competitive? The answer is found largely in the institutional framework by which club play is organized. In Britain chess had been funded by the Sports Council, intercollegiate chess at Harvard was once overseen by the Department of Athletics, and in Chicago public schools, scholastic chess is administered by the Department of Sports Administration. Some high schools offer athletic letters for chess players. To capture the fan loyalty of sports, entrepreneurs organized the United States Chess League in 2005 and receive funding from poker websites. Sixteen teams of strong players, including grandmasters, play each other in competitive but unrated matches. Teams include the New York Knights and the Saint Louis Arch Bishops. Of course, chess is often a simple pastime for fathers and sons or friends on lazy afternoons, merely a more complex version of Candyland, a board game for preschoolers. While casual games are part of the subculture, they are markedly different from tournament play, where the logic of chess as sport is evident.

Local clubs and tournaments are organized under rules established by national organizations such as the USCF. Players in tournaments can gain or lose rating points that measure their skill in comparison to other players. Ratings range from zero (novices start with an assumed rating of 600 but can lose rating points) to over 2800 for a top grandmaster. As of 2004, the average rating for a member of the USCF (including the many scholastic and occasional players) was 1068. Ratings are perhaps the primary motivating factor of organized play and serve as a form of identification. A rating locates one in a competitive hierarchy and determines in which tournaments one can participate and in which division one can play. The outcomes of tournaments affect ratings, based on a complex and changing mathematical computation. Rating points are assumed to be generally accurate, reliable, and universal indicators of a player’s chess skill, even though, as I discuss in chapter 6, they can be misleading. But in practice, ratings translate into status, prestige, and respect.

The chess rating system is distinctive among leisure worlds in shaping player identities, organizing status rankings, and encouraging or dissuading participation. Comparing chess to other organized sports helps decipher the effects of different evaluative systems. For example, baseball players are judged by a set of statistics (batting average, home runs, runs batted in, fielding percentage, stolen bases) that describe their competence in different skill sets. These sorts of statistics diminish competition among teammates, since they emphasize specialization. Chess does not create separate measures for different facets of the game, but players are assigned a single rating. This is a powerful example of “commensuration,” or “the transformation of diff erent entities into a common metric,” affecting personal investment, social comparison, and status competition. Often, as in ice skating, the determination of these measures is altered to achieve what members of the community consider a “fair” distribution.

Chess is famously an activity of the mind, with only the slightest movement of light wood pieces. Yet lengthy games may involve bodily stress, and players are known for lacking physical fitness, even if prior to long matches some adopt exercise regimes. As I discuss in chapter 1, chess is a game of body as well as mind. To play chess requires an awareness of body, and even if competitors do not require muscle, endurance is essential.

Still, sport has multiple meanings, and chess can, at times, fit the metaphor of sport. The patterns of play suggest an aesthetic appeal that links chess to art worlds. If it is neither quite a material art nor a performance art, the beauty of a well-played game is recognized.

Likewise, we link chess to science. Over the centuries, chess has developed a body of systematic knowledge labeled “chess theory.” As in Thomas Kuhn’s scientific paradigms, there are periods of revolution, periods of active incorporation, and periods of normal play. Finally, chess involves brutal competition. Ultimately chess depends on embracing a culture and a status system based on uncertain outcomes in the form of victories and defeats. While we may speak of chess as a leisure world, ignoring those professionals who earn a living from the activity, it creates solidarity, a desire to demonstrate commitment to a local community.

From

From

Okay, so where’s the controversy?

See Eric Simon’s comment.

The rookie hazing is one of my favorite parts of the season. I especially loved the Mets bride and bridesmaids last year. As I recall, Zach Wheeler was the bride. Baseball is the one sport where I really feel I get to know the players, and the rookies seem to enjoy it. Curtis Granderson, who is the leader of the hazing for the Mets these days, said he had to be Pocahontas way back when he was a rookie and that he had fond memories of it, or words to that effect. I can’t recall his actual words. And I give these guys a lot of credit for walking to their hotel dressed like that and owning it.

Eric Simon is obviously neither a baseball fan nor a comic book fan. Besides all of the rookies involved seemed to be having fun with it!

Homoeroticism is somewhat in the eye of the beholder. That and the “emasculation” speaks to me more of Eric Simon’s thoughts than how the rest of the world sees threes events.

Although I have misgivings about the conceptual mash-up of homoeroticism and emasculation and humiliation, and I regard hazing rituals as a throwback to pre-enlightened societies, anything that involves professional athletes walking around in briefs is generally OK with me. :)

Okay… anyone gonna do an all-star rookie baseball card set of hazing photos?

Or at least a website?