I was incredibly, completely, absolutely flat broke during my undergraduate film studies at NYU. Broke like skipping meals to afford rides on the Subway. Broke like working two college jobs, with all of it going to tuition and it never being enough. Broke like having to choose between living in a pest-infested room in Harlem, or not finishing college at all because I couldn’t afford to pay for the dormitories. I was angry, but my anger was a cloak that hid my shame, shame based on a fear that if I was indeed good enough to tell stories, somehow this would have been easier.

I was incredibly, completely, absolutely flat broke during my undergraduate film studies at NYU. Broke like skipping meals to afford rides on the Subway. Broke like working two college jobs, with all of it going to tuition and it never being enough. Broke like having to choose between living in a pest-infested room in Harlem, or not finishing college at all because I couldn’t afford to pay for the dormitories. I was angry, but my anger was a cloak that hid my shame, shame based on a fear that if I was indeed good enough to tell stories, somehow this would have been easier.

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Commentary, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 264

Blog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Black Widow, Top News, bryan edward hill, Commentary, Add a tag

Blog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books for the News, Commentary, Biology, Reviews, Add a tag

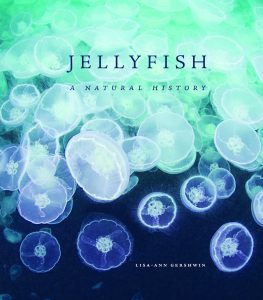

Just in time for this weekend’s unofficial “start of summer” gong, Nature (yea, that Nature—though also, ostensibly, “nature,” the wilder of nouns, not that other one qua Lucretius’s De rerum natura) came through with a review of Lisa-ann Gershwin’s Jellyfish: A Natural History. Stuck behind a paywall? Here it is in its glory, for your holiday reads:

One resembles an exquisitely ruffled and pleated confection of pale silk chiffon; another, a tangle of bioluminescent necklaces cascading from a bauble. Both marine drifters (Desmonema glaciale and Physalia) feature in jellyfish expert Gershwin’s absorbing coffee-table book on this transparent group with three evolutionary lineages. Succinct science is intercut with surreal portraiture — from the twinkling Santa’s hat jellyfish (Periphylla periphylla) to the delicate blue by-the-wind sailor (Velella velella).

To read more about Jellyfish, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books for the News, Commentary, Literature, Add a tag

From “Live through This,” by Catherine Hollis, her recent essay at Public Books on how much of our own lives we construct when we read and write memoirs:

In The Dead Ladies Project: Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries, Jessa Crispin, the scrappy founding editor of Bookslut and Spolia, finds herself at an impasse when a suicide threat brings the Chicago police to her apartment. She needs a reason to live, and turns to the dead for help. “The writers and artists and composers who kept me company in the late hours of the night: I needed to know how they did it.” How did they stay alive? She decides to go visit them—her “dead ladies”—in Europe, and leave the husk of her old life behind. Crispin’s list includes men and women, exiles and expatriates, each of whom is paired with a European city. Her first port of call is Berlin, and William James. Rather than explicitly narrating her own struggle, Crispin focuses on James’s depressive crisis in Berlin, where as a young man he learned how to disentangle his thoughts and desires from his father’s. Out of James’s own decision to live—“my first act of free will shall be to believe in free will”—the rest of his life takes shape. Crispin reconstructs what it might have felt like to be William James before he was William James, professor at Harvard and author of The Varieties of Religious Experience. If he can live through the uncertainty of a life-in-progress, so too might she.

But not before checking in with Nora Barnacle in Trieste, Rebecca West in Sarajevo, Margaret Anderson in the south of France, W. Somerset Maugham in St. Petersburg, Jean Rhys in London, and the miraculous and amazing surrealist photographer Claude Cahun on Jersey Island. Through each biographical anecdote, each place, Crispin analyzes some issue at work in her own life: wives and mistresses, revolutionaries with messy love lives, and the problem of carting around a suicidal brain. Crispin travels with one suitcase, but a good deal of emotional baggage. While she focuses on each subject’s pain, what she’s seeking is how these writers and artists alchemized their suffering into art, and how that transmutation opens up an individual’s story to others. . . .

In the end, learning how other women and men decided to live helps Crispin decide that suicide is a failure of imagination. “Here is something else you could do,” Crispin’s ladies tell her; here is some other way to live.

To read the piece in full at Public Books, click here.

To read more about The Dead Ladies Project, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Commentary, History and Philosophy of Science, Add a tag

Michael Riordan, coauthor of Tunnel Visions: The Rise and Fall of the Superconducting Supercollider penned a recent op-ed for the New York Times on United Technologies and their subsidiary, the air-conditioning equipment maker Carrier Corporation, who plans “to transfer its Indianapolis plant’s manufacturing operations and about 1,400 jobs to Monterrey, Mexico.” Read a brief excerpt below, in which the author begins to untangle a web of corporate (mis)behavior, taxpayer investment, government policy, job exports—and their consequences.

***

The transfers of domestic manufacturing jobs to Mexico and Asia have benefited Americans by bringing cheaper consumer goods to our shores and stores. But when the victims of these moves can find only lower-wage jobs at Target or Walmart, and residents of these blighted cities have much less money to spend, is that a fair distribution of the savings and costs?

Recognizing this complex phenomenon, I can begin to understand the great upwelling of working-class support for Bernie Sanders and Donald J. Trump — especially for the latter in regions of postindustrial America left behind by these jarring economic dislocations.

And as a United Technologies shareholder, I have to admit to a gnawing sense of guilt in unwittingly helping to foster this job exodus. In pursuing returns, are shareholders putting pressure on executives to slash costs by exporting good-paying jobs to developing nations?

The core problem is that shareholder returns — and executive rewards — became the paramount goals of corporations beginning in the 1980s, as Hedrick Smith reported in his 2012 book, “Who Stole the American Dream?” Instead of rolling some of the profits back into building their industries and educating workers, executives began cutting costs and jobs to improve their bottom lines, often using the proceeds to raise dividends or buy back stock, which United Technologies began doing extensively last year.

And an easy way to boost profits is to transfer jobs to other countries.

To read more about Tunnel Visions, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: History and Philosophy of Science, Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Commentary, Add a tag

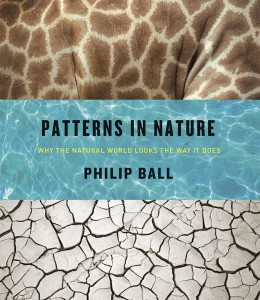

It might only be April, but there’s already one foregone conclusion: Philip Ball’s Patterns in Nature is “The Most Beautiful Book of 2016” at Publishers Weekly. As Ball writes:

The topic is inherently visual, concerned as it is with the sheer splendor of nature’s artistry, from snowflakes to sand dunes to rivers and galaxies. But I was frustrated that my earlier efforts, while delving into the scientific issues in some depth, never secured the resources to do justice to the imagery. This is a science that, heedless of traditional boundaries between physics, chemistry, biology and geology, must be seen to be appreciated. We have probably already sensed the deep pattern of a tree’s branches, of a mackerel sky laced with clouds, of the organized whirlpools in turbulent water. Just by looking carefully at these things, we are halfway to an answer.

I am thrilled at last to be able to show here the true riches of nature’s creativity. It is not mere mysticism to perceive profound unity in the repetition of themes that these images display. Richard Feynman, a scientist not given to flights of fancy, expressed it perfectly: “Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.”

You can read more at PW and check out samples from the book’s more than 250 color photographs, or visit a recent profile in the Wall Street Journal here.

To read more about Patterns in Nature, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: eccc, eccc 2016, education and comics, Comics, Conventions, education, Commentary, Add a tag

Comic books continue to reach mainstream audiences and have stretched into academia. At the Panels and Pedagogy: Teaching Comics panel, panelists aimed to help answer questions that arise about—teaching comic books, formal instruction for creators, and establishing the academic discipline of comics. Where do comic books fit in your academic life?

Comic books continue to reach mainstream audiences and have stretched into academia. At the Panels and Pedagogy: Teaching Comics panel, panelists aimed to help answer questions that arise about—teaching comic books, formal instruction for creators, and establishing the academic discipline of comics. Where do comic books fit in your academic life?

Blog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Los Angeles, UFO, haunting, LA, Nerdlebrity News, chris hardwick, Wondercon, Top News, Wonder-Con, Nerdist News, Small Presses, podcast, Sports, Conventions, Culture, Commentary, Podcasts and other media, Podcasts, Add a tag

By Nicholas Eskey If you label yourself a “nerd” and wear it with pride, undoubtedly you already follow Chris Hardwick’s Nerdist News. The quick witted comedian and mega-nerd took heads the podcast driven news network for nerds with a wonderful collection of colleagues and special guests, discussing everything from the current state of all things […]

By Nicholas Eskey If you label yourself a “nerd” and wear it with pride, undoubtedly you already follow Chris Hardwick’s Nerdist News. The quick witted comedian and mega-nerd took heads the podcast driven news network for nerds with a wonderful collection of colleagues and special guests, discussing everything from the current state of all things […]

Blog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Literature, Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Add a tag

For those of you who missed it, here is Levi Stahl’s 31-part Twitter essay from late last week, which responds to an op-ed in the New York Times by columnist Ross Douthat comparing Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz to Widmerpool, the anti-anti-hero from Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time:

To read more about A Dance to the Music of Time, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Film and Media, Books for the News, Commentary, Add a tag

To commemorate the third anniversary of Roger Ebert’s death, we asked UCP film studies editor Rodney Powell to consider his legacy. Read after the jump below.

***

It’s three years since Roger Ebert’s death; for three years we’ve been deprived of his reviews, “Great Movies” essays, and journal entries. Fortunately most of his writing remains available online, and the University of Chicago Press has been privileged to publish three of his books—Awake in the Dark, Scorsese by Ebert, and The Great Movies III, with a fourth, a reprint of Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook just out. And there’s more to come, with The Great Movies IV due this fall.

So I think this should be an occasion for celebrating rather than lamenting. My own hope is that, as the celebrity status he attained fades from memory, he will be recognized for the brilliant writer he was. Within the confines of the shorter forms in which he wrote, he was an absolute master. Of course not every piece was at the same high level, but a remarkable percentage of his vast output will, I think, stand the test of time. Here I will only mention the high regard in which his work is held by film scholar extraordinaire David Bordwell (see his Forewords to Awake and GM III) as additional proof of its value.

I provided my own brief appreciation of Ebert’s writing back in 2013, and I still agree with that appraisal, particularly this statement: “Like other lasting critics, he could make his readers understand the moral qualities of the works he valued most by revealing how they made audiences think about the Big Questions—not by preaching, but by engaging with the dramatic complexities at the core of those films.”

And I don’t think I can do any better than the final paragraph of that piece: “If writers give us the best of themselves in their writing, Ebert’s gifts to his readers were abundant—intelligence, wit, clarity, and generosity expressed in prose that is both engaging and thought-provoking. As long as the printed word survives, those gifts of his large spirit will be available. And death shall have no dominion.”

Amen.

To read more about books by Roger Ebert published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: fiction, Commentary, columns, Bryan Hill, sarah conner, Add a tag

by Bryan Hill “Thank you, Sarah for your courage through the dark years. You must be stronger than you imagine you can be. You must survive.” – Kyle Reese The year is 1985, my family just got cable television, and there was a chrome nightmare coming to get me. James Cameron’s THE TERMINATOR is the […]

by Bryan Hill “Thank you, Sarah for your courage through the dark years. You must be stronger than you imagine you can be. You must survive.” – Kyle Reese The year is 1985, my family just got cable television, and there was a chrome nightmare coming to get me. James Cameron’s THE TERMINATOR is the […]

Blog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Literature, Books for the News, Commentary, Politics and Current Events, Add a tag

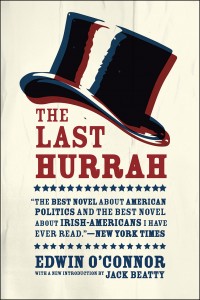

In timely coincidence with today’s primaries and the book’s return to print, The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor received some well-tailored praise from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Hall, writing in the Columbia Daily Herald, who suggests we:

Take a breather from the daily pounding of politics and reflect: chaos, confusion, and gutter campaigning are not new. . . . Even today’s politics are not speeding away. We have survived travail through democracy. Good and thoughtful fiction lets us pause and reflect.

Honing in on The Last Hurrah, an almost-story adapted from the life of notorious Boston mayor James Michael Curley, he writes of the book’s foreboding about the nature of the relationship between media and politics:

Another poignant tale of American politics is The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor. Set in an old and mainline northeastern city, the novel examines the dying days of machine politics when largess held voters in sway. Frank Skeffington, 72, believes he is entitled to one more term. His political compass loses its bearing against a young, charismatic challenger, void of political experience but adorned with war medals and good looks. O’Connor’s 1956 novel was prescient in portraying the impact television would have on politics. While The Last Hurrah lacks the intellectual complexity of All the King’s Men, it raises good questions about how religion, ethnicity, class and economics foster into political alliance—questions still relevant starting even at the city and county level.

To read more about The Last Hurrah, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Commentary, Biology, Add a tag

Boing Boing recently profiled Tim Halliday’s The Book of Frogs: A Life-Size Guide to Six Hundred Species from Around the World, but the real coup was a live link to sample pages, which showcase some of the majestically weird amphibians curated therein. You can see a handful of those images after the jump, but be sure to check out a glossy PDF of even more, via (full-size) additional samples posted to the book’s UCP site.

***

To read more about The Book of Frogs, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Commentary, Art and Architecture, Add a tag

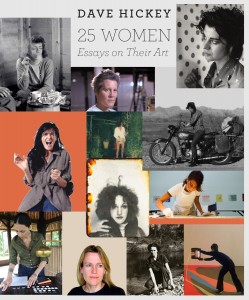

What follows below is a very brief excerpt from a feature-length interview with Dave Hickey, whose book 25 Women: Essays on Their Art published this fall, over at Momus.

***

Tell me about the timing. Why did you decide to produce 25 Women when you did?

I was putting together a book of what I considered to be my best essays about what I considered to be the best art. I got up to about ten or twelve essays and I realized that most of these essays were about the art of women artists, so I shifted my hand on the tiller. Also, I wanted to memorialize Marcia Tucker, so I did that. I thought it would be a kick.

You say in your introduction that it’s not “a fair book.” What do you mean by that? How would it look if it was fair?

Well, there are lots of women artists whose work I like, about whom I never had a chance to write. Agnes Martin, Cindy Sherman, and Hannah Wilke come to mind. This was mostly in the seventies when men couldn’t write about women artists if a woman writer was available, and there always was. I also wrote some essays that weren’t salvageable, in my opinion, because the writing was not good. I have essays about Joan Snyder, Patricia Tillman, Helen Frankenthaler, and others that I really screwed up. Also I have written about some women artists whose work has changed so dramatically that what I had to say was irrelevant.

So the book is not fair, nor does it embody a singular theme about the plight of women artists. I’m like Donald Trump in that: I like winners. So the book is not about the plight of women artists in general. This is a flaw I cannot fix. The tenor of contemporary criticism is sociological, and since I am neither clairvoyant nor a sociologist, I have no insight into what is called the issue of “women’s identity.” I don’t understand women, but I don’t understand a lot of things. The rule today is that you can’t write about the art of women artists without having a foundational opinion of all women artists. I don’t have that.

To read the interview in full, click here.

To read more about 25 Women, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Politics and Current Events, Add a tag

A free chapter from Sixteen for ’16: A Progressive Agenda for a Better America

by Salvatore Babones (Policy Press)

***

Back in the good old days, that is to say the mid-1990s, taxpayers with annual incomes over $500,000 paid federal income taxes at an average effective rate of 30.4%. For 2012, the latest year for which data are available, the equivalent figure was 22.0%.

The much-ballyhooed January 1, 2013 tax deal that made the Bush-era tax cuts permanent for all except the very well-off will do little to reverse this trend: The deal that passed Congress only restores pre-Bush rates on the last few dollars of earned income, not on the majority of earned income, on corporate dividends, or on most investment gains.

Someone has had a very big tax cut in recent years, and the chances are that someone is not you. In the 1990s taxes on high incomes were already low by historical standards. Today, they are even lower. The super-rich are able to lower their taxes even further through a multitude of tax minimization and tax avoidance strategies.

The very tax system itself has in many ways been structured to meet the needs of the super-rich, resulting in a wide variety of situations in which people can multiply their fortunes without actually having to pay tax. In general, it is also much easier to hide income when most of your income comes from investments than when your income is reported on regular W-2 statements from your employer direct to the IRS.

Whatever our tax statistics say about the tax rates of the super-rich, we can be sure they are lower in reality. At the same time that their tax rates are going down, the annual incomes of highly paid Americans are going through the roof.

In the 1990s the average income of the top 0.1% of American taxpayers was around $3.6 million. In 2012 it was nearly $6.4 million.6 And yes, these figures have been adjusted for inflation. Thanks to the careful database work of Capital in the Twenty-First Century author Thomas Piketty and his colleagues, it is now relatively easy to track and compare the incomes of the top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.01%. The historical comparisons don’t make for pretty reading.

Forget the merely well-off 1%. In the 21st century the top 0.1% of American households have consistently taken home more than 10% of all the income in the country, up from 3% in the 1970s.7 And these figures only include realized income: that is to say, income booked and reported to the tax authorities. If you own a company that doubles in value but you don’t sell any shares, you don’t have any income. Ditto land, buildings, airplanes, yachts, artwork, coins, stamps, etc.

High inequality plus low taxes equals fiscal crisis. The rich are taking more and more money out of the economy, but they are not returning it in the form of taxes. The result is that the US government no longer has the resources it needs to properly govern the country. The country needs universal preschool, universal healthcare, and a massive government-sponsored jobs program. The country needs a complete renewal of its crumbling human and physical infrastructure. The country needs funds for everything from the cleanup of atomic waste in Hanford, Washington to improvements at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. And the country needs higher taxes on today’s higher incomes to pay for it all.

In 2010 the United States government collected a smaller proportion of the nation’s total national income in income taxes than at any time since 1950.8 That figure has since rebounded, but it is still well below the average from 1996-2001. Under current law the federal income tax take is projected to rise from the historic low of 6.1% in 2010 to 8.6% of national income in 2016. This is an improvement over recent years, but it is still far below the average of 9.5% for the years 1998-2001, the last time the federal government actually ran a budget surplus.

The top marginal tax rate on the highest incomes is now 39.6%, as it was in the 1990s. This is still a far cry from the 50% top tax bracket of the 1970s or the 70% top tax bracket of the 1960s, never mind the 91-92% top tax brackets of the 1950s.10 The return to 1990s levels is a good start, but the next President should push to go much farther back because the tax system has been moving in the wrong direction for a very long time. High incomes are much higher than they ever were and people with high incomes pay much less tax than at almost any time in our modern history. The result, unsurprisingly, has been the enormous concentration of income among a small, powerful elite documented by Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century but no less obvious for all to see.

The concentration of income among a powerful elite may be very good for members of that elite, but it is bad for our society, bad for our democracy, and even bad for our economy. Socially, highly concentrated incomes undermine our national institutions and warp our way of life. For example, people who can afford to send their children to exclusive private schools cease to care for the health of public education, or they erect barriers to separate “their” public schools from everyone else’s public schools. Similarly, people who can afford the very best private healthcare care little about ensuring high-quality public healthcare. People who fly private jets care little about congestion at public airports. People who drink imported bottled water care little about the poisoning of rivers and underground aquifers. Enormous differences in income inevitably create enormous distances between people. The United States is starting to resemble the fractured societies of Africa and Latin America, where the rich live in ated “communities” with armed guards who enforce the exclusion of the lower classes—except to allow them entry as maids and gardeners.

These nefarious effects of inequality can already be seen in America’s sunbelt cities, where there are fine gradations of gated communities: armed guards for the super-rich, unarmed guards for the merely well- off, keypad security for the middle class, and on down the line to the unprotected poor. We should be ashamed, one and all.

Politically, highly concentrated incomes threaten the integrity of American democracy by fostering corruption of all kinds. When the income differences between regulators and the industries they regulate are small, we can count on regulators to look after our interests.

But when industry executives make two or three (or ten) times as much as regulators, it is almost impossible to prevent corruption. Even where there is no outright corruption, it is impossible for regulators to retain talented staff. People will take modest income cuts to work in secure public sector employment. They will not take massive income cuts. Those who do are often just doing a few years on the inside so they can better evade regulation when they go back to the private sector. When doing a few years on the inside includes serving in Congress merely as way to get a high-paying job as a lobbyist, we are in serious trouble.

Along with highly concentrated incomes come vote buying and voter suppression. When the stakes are so high, people will play dirty. No one knows how many local boards of one kind or another around the country have been captured by local economic interests, but the number must be very large.

Economically, highly concentrated incomes ensconce economic privilege, suppress intergenerational mobility, and can ultimately lead to the total breakdown of the free market as a system for effi driving production and consumption decisions. Privilege is perpetuated by excessive incomes because with enough money the advantages of wealth overpower any amount of talent and effort on the part of those who are born poor.

Nineteenth-century English novels were obsessed with inheritance and marriage because in that incredibly unequal society birth trumped everything else. Twenty-first-century America has now reached similar levels of income concentration among a powerful elite. To make this point graphically clear, a family with a billion-dollar fortune that does absolutely no planning to avoid the 40% tax on large estates and no paid work whatsoever can comfortably take out $15 million a year to live on (after taxes, adjusted for inflation) in perpetuity until the end of history—while still growing the estate. That’s how mind-bogglingly large a billion-dollar fortune is.

But probably the least recognized impact of high inequality on our economy is that it severely impairs the efficient operation of the free market itself. Market pricing is at its core a mechanism for rationing. The market directs limited resources to the places where they command the highest prices. The basic idea of rationing by price is that prices encourage people to carefully weigh their purchases against each other—in other words, to economize.

In an economy where everyone earns roughly the same income, rationing by price works just fine for most goods. People take care of their necessities first. Then they can choose whether to spend their extra money on eating out, taking vacations, renovating their homes, or saving up to buy something big like a boat. Because all of these goods are priced in the same currency, people can directly compare their values against each other. And if everyone has roughly the same amount of money to spend, market prices represent roughly the same values for different people. If you and I have the same income, a $20 restaurant meal means as much to me as it does to you.

Problems set in when incomes are very unequal. For people with extraordinarily high incomes, prices become meaningless. What does a $20 restaurant meal mean to someone who makes $20 million a year? Nothing.

The result is incredible waste as the market economy no longer forces people to economize. When rich people accumulate dozens of cars, maintain yachts they only use once a year, or have servants order fresh-cut flowers every day for houses they rarely visit, they are wasting resources that could be put to much better use by other people. Waste like this invalidates the foundational principle of modern economics: that the market maximizes the total utility of society.

That principle only holds if a dollar has the same meaning for you as it does for me. Highly concentrated incomes undermine the whole idea of the market as an economy—that is, as something that economizes. And that is the strongest argument for much higher taxes on higher incomes. There are many ways to reduce inequality, but the simplest and most efficient way is through taxation. The goal of income taxes should be to tilt the field so that earning an after-tax dollar means just as much to a CEO as to a fast food worker. That’s why a 90% marginal tax on incomes over a million dollars is entirely appropriate.

For a poor person who pays no income tax, a $20 restaurant meal costs $20. That person must make a real sacrifice to eat out. For a CEO with a 90% marginal tax rate, a $20 restaurant meal costs $200 in before-tax income. That may not be a huge sacrifice for someone who makes several million dollars a year, but it does change the equation. A CEO may not hesitate to eat out, but may hesitate to buy a private jet when flying business class will suffice.

To be sure, we need higher taxes on higher incomes to raise money for government. But we also need higher taxes on higher incomes just to make the economy work properly. That’s why the economy worked so much better in the high-tax 1950s and 1960s than it has since.

The ultimate goal of income taxes should be to make money as meaningful to a millionaire as it is to you or me. If we can’t quite get there in the next few years, we can certainly get closer than we are. One of President Obama’s most important accomplishments has been to set us on the path toward economic sanity by raising taxes on the highest incomes. The next President should build on this legacy—and in a big way.

***

Salvatore Babones is associate professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney.

To read more about Sixteen for ’16, click here.

Add a Comment

Blog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Diversity, Commentary, Batman, Bryan Hill, Add a tag

When Heidi offered her forum to me to discuss issues of diversity, I was hesitant. I admire activism, but I’m a writer and my passion is talking storytelling and character. The opportunity made me feel unsafe, like somehow I would put storytelling in danger by raising the issue of diversity within it. I realized, during a long play session of FALLOUT 4 (my chosen tool for meditation), that my safety wasn’t at stake. I was protecting my comfort. Diversity is an uncomfortable conversation, especially on the internet. Writing popular fiction is kin to walking barefoot on hot coals. If you ignore the heat, you can make it to the other side. The moment you think about what’s underneath you, the flame takes you forever.

Blog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Comics, Retailing & Marketing, Commentary, rebirth, DC Comics, Top News, Top Comics, The Retailer's View, DC Rebirth, Add a tag

It’s been quite a while since the last edition of The Retailer’s View, and there are several reasons for that. Almost all of them can be grouped under the heading “year one of a business is tricky as hell”, though a bit can be attributed to the emotional drop I encountered at the end of […]

It’s been quite a while since the last edition of The Retailer’s View, and there are several reasons for that. Almost all of them can be grouped under the heading “year one of a business is tricky as hell”, though a bit can be attributed to the emotional drop I encountered at the end of […]

Blog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: History, Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Commentary, Add a tag

Below follows an excerpt from “Flint’s toxic water crisis was 50 years in the making,” Andrew R. Highsmith’s op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, which builds on the scholarship of his book Demolition Means Progress: Flint, Michigan, and the Fate of the American Metropolis. Read his piece in full here.

***

As with so many environmental disasters, this one was preventable. Evidence suggests that the simple failure to use proper anti-corrosive agents led to the leaching of lead into the city’s water. It has also become apparent that the slow responses of local, state and federal officials to this crisis — as well as their penchant for obfuscation — prolonged the lead exposure.

It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that Flint’s predicament is simply the result of government mismanagement. It’s also the product of a variety of larger structural problems that are much more difficult to untangle and remedy.

Over the past three-quarters of a century, waves of deindustrialization, disinvestment and depopulation eviscerated Flint’s tax base, making it all but impossible to improve — or even maintain — the city’s crumbling infrastructure. Flint — which once claimed 200,000 residents — now contains fewer than 100,000, nearly half impoverished, more than half African American. The economic prospects of locals are grim. After decades of plant closures and layoffs, GM’s workforce in the area, which once surpassed 80,000, is less than 10,000. The hemorrhaging of jobs has produced unemployment rates that routinely reach into the double digits. . . .

If there was ever a canary in Flint’s coal mine, it may have been Ailene Butler. When she stepped forward in 1966, she crystallized the tight connections between environmental inequality and social injustice. To be sure, much has changed since Butler sounded the alarm half a century ago. Whereas in the 1960s it was the encroachment of industrial plants upon black neighborhoods that fueled local resentment, Flint’s current water crisis stems in many ways from the absence of those plants — and the jobs, taxes, services and infrastructure they supported. Still, looking ahead at Flint’s uncertain future, Butler’s message seems more relevant than ever.

To read more about Demolition Means Progress, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books for the News, Commentary, Music, Add a tag

Photo by: Ariel Uribe for the Chicago Maroon.

Full of “blood and thunder“—words for the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s staging of Giuseppe Verdi’s Nabucco, an amalgamation of quasi-stories from the Book of Jeremiah and the Book of Daniel coalesced around a love triangle, here revived for the first time since 1998. On the heels of its opening—the full run is from January 23 to February 12—UCP hosted a talk and dinner featuring a lecture “Nabucco and the Verdi Edition” by Francesco Ives. That Verdi Edition, The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, is the most comprehensive critical edition of the composer’s works. In addition to publishing its many volumes, the University of Chicago Press also hosts a website devoted to all aspects of the project, which you can visit here; to do justice to the scope and necessity of the Verdi Edition, here’s an excerpt from “Why a Critical Edition?” on that same site:

The need for a new edition of Verdi’s works is intimately tied to the history of earlier publications of the operas and other compositions. When Verdi completed the autograph orchestral manuscript of an opera, manuscript copies were made by the theater that commissioned the work or by his publisher (usually Casa Ricordi). These copies were used in performance, and most of the autograph scores became part of the Ricordi archives. Copies of the copies were made, and orchestral materials were extracted for performances. With the possible exception of his last operas, Otello and Falstaff, Verdi played no part whatever in preparing the printed scores: almost all printed editions of his works were prepared by Ricordi after Verdi’s death in 1901.

Predictably, these copying and printing practices have yielded vocal and orchestral parts that differ drastically from the autograph scores. Indeed, the problem of operas performed using unreliable parts and scores dates to Verdi’s own lifetime. After the premieres of Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata, for example, Verdi wrote to Ricordi on 24 October 1855: “I complain bitterly of the editions of my last operas, made with such little care, and filled with an infinite number of errors.”

Copyists and musicians who prepared these errant printed editions were not consciously falsifying Verdi’s text. They merely glossed over particularities of Verdi’s notation (e.g., the simultaneous use of different dynamic levels—“p” and “pp”, for instance) and altered details of his orchestration, which differed considerably from the style of Puccini, whose music dominated Italian opera when the printed editions of Verdi’s works were prepared. These editions, which in certain details drastically compromise the composer’s original text, are the scores that are used today, except where the critical edition has made reliable scores available.

The critical edition of the complete works of Verdi undertaken jointly by the University of Chicago Press and Casa Ricordi is finally correcting this situation.

To read more about The Works of Giuseppe Verdi, click here.

To visit the project’s website, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Art and Architecture, Add a tag

The University of Chicago Press: you’ve got the answer(s), we’ve got the question(s).

(And by questions, I mean Dave Hickey’s other books.)

To read more about The Invisible Dragon, click here.

To read more about 25 Women: Essays on Their Art, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Politics and Current Events, Add a tag

The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform is having quite a week—and quite an election season, in general. The book was adopted early by Nate Silver at his FiveThirtyEight blog, which led to explorations of its hypothesis here and here, and most recently here: where Silver posits the book as the most “misunderstood” of the 2016 primary season.

The point of Silver’s statement rests on whether or not a Trump nomination would destroy the Republican Party. The book’s argument is that party elites—unelected insiders—control who ultimately ends up nominated at the convention, and that decision is made many months before the primary campaign season even begins. Was anyone but Trump the nominee (say Marco Rubio, or even Jeb Bush), then The Party Decides had it right all along; if Republicans put forward DT, then it may be less a sign that the statistically supported data of the book is incorrect, and more a case of the possible dissolution of the Grand Old Party.

In the meantime, you can hear more about the book and what a Trump nomination might signify on today’s episode of The Brian Lehrer Show below:

To read more about The Party Decides, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Economics, Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Add a tag

“If the US economy is so good, why does it feel so bad?”*

by Salvatore Babones

(*adapted from Sixteen for ’16: A Progressive Agenda for a Better America, first published on the Policy Press Blog)

***

With a 2 percent annual growth rate, 5 percent unemployment, and zero inflation, the US economy is the envy of the world. Growth seems to be rising and unemployment seems to be falling, which means that most analysts expect an even better US economy in 2016. Throw in low gas prices and a strong dollar, and what’s not to like?

If the US economy is doing so well, why are ordinary people so unhappy with their own economic prospects?

The aggregate US economy may be growing but most people’s personal economies are not. Census Bureau data show that real per capita income is still below 2007 levels—despite six years of solid economic growth. And Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that despite today’s low unemployment rates the jobs still haven’t come back.

Back in 2006 the employment rate of the civilian population—the proportion of adults who had jobs—was over 63 percent. Allowing for people who are still in school, people who are retired, people who are disabled, and people who prefer not to work, that was just about everyone. When the economy is doing well, people who want jobs can get jobs.

Compare that with 2015. For all of 2015 to date the employment rate has been stuck below 60 percent. In fact, the employment rate has been not risen above 60 percent since the technical beginning of the “recovery” in June, 2009. Over the last six years, the economy has recovered. Employment has not.

The difference between the 63 percent employment rate of 2006 and the (well under) 60 percent employment rate of 2015 is roughly 7.5 million people. That’s the number of jobs missing in today’s roaring economy. Bringing today’s employment rate back up to 2006 levels would require the creation of more than 7.5 million new jobs.

What’s more, since the Global Financial Crisis there has been a shift from full-time to part-time employment. Some 2.5 million full-time jobs have disappeared, to be replaced by part-time employment. Assuming that people have basically the same preferences as they had before the recession hit, this means that the US economy is really short 10 million full-time jobs.

And remember, this is the economy at its best. The current “recovery” won’t last forever. It is already the fourth longest expansion of all time and about to overtake the World War II period to become the third longest. If the next recession hits while the economy is already 10 million jobs short of full employment, God help us.

The managers of the US economy don’t seem to be worried about this. On December 16, 2015 the Federal Reserve raised interest rates (albeit by a tiny amount) for the first time in seven years. The Fed expects that “economic activity will continue to expand at a moderate pace and labor market indicators will continue to strengthen.” In other words, the Fed expects more good news.

More good news for whom? As analyses from the Financial Times show, banks are increasingly parking their money at the Fed, not lending it out to businesses and consumers. Along with the Fed’s increase in lending rates (from 0 to 0.25 percent) came an increase in the interest rate the Fed pays banks on their own deposits at the Fed (from 0.25 percent to 0.5 percent).

For the last six years banks have parked trillions of dollars of excess funds in their accounts at the Federal Reserve. After all, they can earn 0.25 percent risk-free by borrowing money from the Fed and placing it directly in their own accounts at the Fed. Banks now hold some $2.5 trillion in excess reserves in these accounts. Those holdings give banks collectively an extra $6 billion in annual risk-free profits.

Before the Global Financial Crisis, US banks held virtually $0 in excess reserves in their Federal Reserve accounts.

What we see today is a US economy that is great for banks, great for bankers, and not so great for ordinary workers. Employment rates are down, employment hours are down, and wages are down. Bank profits are up, up, up to record levels. It’s no wonder that ordinary people are not as optimistic as the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

In the end, the Fed can’t fix the problems of the US economy. The Fed can help the banks (and the bankers who serve on its boards) but it can’t make companies hire more people. Only government can do that, and the US government has shown no willingness to create jobs in this recession, or even in this century.

The US government should be borrowing that cheap Fed money and using it to put people to work. Education, healthcare, and infrastructure could all absorb millions of workers to do jobs that desperately need to be done. President Obama should make this clear to Congress and put people to work. Fixing the jobs crisis can’t wait for the next president—or the next recession. It is already long overdue.

Salvatore Babones is associate professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney. His new book Sixteen for ’16: A Progressive Agenda for a Better America is the first book in the Policy Press Shorts series. For more information about the policies proposed in Sixteen for ’16, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Sociology, Books for the News, Commentary, Publicity, Add a tag

The controversy surrounding Alice Goffman’s On the Run is nothing new—the book’s appearance was met with both laudatory curiosity and defensive criticism, from within and outside academic sociology. On the Run offers an ethnographic account based on Goffman’s work in the field—and the field happens to be a mixed-income, West Philadelphia neighborhood, whose largely African American residents lived their lives under the persistence presence of the cops, whose pervasive policing left Goffman’s subjects, the members of her community, caught in a web of presumed criminality. The elephant(s) in the room: how does a privileged white woman engage in this kind of (often passé) participant-observer research without constantly self-checking her positionality? How can this type of book—and its more sensational elements—be true to the word? Who has permission to write about whom? And what happens when these questions leave the back-and-forth behind the closed doors of the academy and bring up very real suggestions about legal culpability, fabrication, and the politics of representation?

In a long-form piece for the New York Times Magazine, Gideon Lewis-Kraus assesses Goffman’s predicament and how her personal experiences shaped several of the more controversial aspects of the book’s account. All the while, he traces the book’s emergence during a crucial (and heated) moment for the history of sociology, when data-driven analysis has bumped the hybrid reportage/qualitative ethnography favored by Goffman into the margins of social science, and considers how the events following its publication played out in the media—and what all of this might mean for Goffman’s own future (and those of her subjects, neighbors, peers) and that of her discipline.

Following this excerpt, you can read the piece in full here.

***

But what her critics can’t imagine is that perhaps both of the accounts she has given are true at the same time — that this represents exactly the bridging of the social gap that so many observers find unbridgeable. From the immediate view of a participant, this was a manhunt; from the detached view of an observer, this was a ritual. The account in the book was that of Goffman the participant, who had become so enmeshed in this community that she felt the need for vengeance ‘‘in my bones.’’ The account Goffman provided in response to the felony accusation (which read as if dictated by a lawyer, which it might well have been) was written by Goffman the observer, the stranger to the community who can see that the reason these actors give for their behavior — revenge — is given by the powerless as an attempt to save face; that though this talk was important, it was talk all the same.

The problem of either-or is one that is made perhaps inevitable by the metaphor of ‘‘immersion.’’ The anthropologist Caitlin Zaloom, who studies economic relationships, explained to me that it’s a metaphor her own field has long given up on. The metaphor asks us to imagine a researcher underwater — that is, imperiled, unreachable from above — who then returns to the sun and air, newly qualified to report on the darkness below because the experience has put a chill in her bones. This narrative of transformation is what strikes critics like Rios as so patronizing and self-congratulatory. But Goffman herself never understood her work to be ‘‘immersive’’ in that way. The almost impossible challenge Goffman thus set before herself is the representation of both these views — of drive as manhunt and drive as ritual — in all their simultaneity.

Goffman could have covered herself by adding another paragraph of analysis, one that would have contextualized but also undercut the scene as the participants experienced it. Almost all of her early readers thought she should do that. It would have made her life easier. But she didn’t. This was a book about men whose entire lives — whose whole network of relationships — had been criminalized, and she did not hesitate to criminalize her own. She threw in her lot.

To read more about On the Run, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Literature, Books for the News, Commentary, Publicity, Add a tag

In addition to making an appearance in the “Briefly Noted” books section of the New Yorker, the Cheers equivalent of finding an empty chair between Norm and Cliff at the bar, this week Jessa Crispin, author of The Dead Ladies Project, published an opinion piece at the New York Times on singlehood and St. Teresa, riffing on her pilgrimage to Ávila, the saint’s town. Here’s a nugget of what’s waiting over at the NYT:

Five hundred years after St. Teresa, and there are still very few models for women of how to live outside of coupledom, whether that is the result of a choice or just bad luck. I can’t remember the last time I saw a television show or a film about a single woman, unless her single status was a problem to be solved or an illustration of how deeply damaged she was. This continues even as more and more women are staying single longer and longer.

I’ve been single for the most part going on 11 years now, and so I have heard every derogatory, patronizing, demeaning thing said about single women. “There has to be someone for you,” a married woman friend once said exasperatedly after I recounted another bad date. Implying, unconsciously, that there must be one man somewhere on the planet who could stand to be around me for more than a few days at a time.

And so it’s hard to get people to understand why a woman would ever choose to live a life alone. We no longer have to choose between being a brain and a body, but I can’t help but think that we lose something when we couple up, and maybe that thing is worth preserving. I pointed out to a different friend that it was the nuns who were the most socially engaged, working with the world’s most vulnerable. My friend, married, asked “as devil’s advocate” whether they were simply compensating for the lack of romantic love and children with their social concern. Yes, I said, maybe. “But we all have needs that aren’t met, and we’re all looking for substitutes.”

To read more about The Dead Ladies Project, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Biology, Add a tag

From an expansive profile of lion expert and University of Chicago Press author Craig Packer at the New York Times:

Like many scientists, Dr. Packer, a professor of ecology, evolution and behavior at the University of Minnesota, has fought his share of battles in the pages of professional journals.

But he has also tangled with far more formidable adversaries than dissenting colleagues. He has sparred with angry trophy hunters, taken on corrupt politicians, fended off death threats and, in one case, thwarted a mugging. Like the lioness, his opponents discovered that he is unlikely to give ground.

“My reflex is to confront the danger and go right at it,” he said.

Dr. Packer’s boldness — he concedes some might call it naïveté — eventually led to the upheaval of his life in Tanzania, where for 35 years he ran the Serengeti Lion Project, dividing his time between Minnesota and Africa. Assisted by a bevy of graduate students, he conducted studies of lion behavior that have shaped much of what scientists understand about the big cats.

But in 2014, Tanzanian wildlife officials withdrew his research permit, accusing him of “tarnishing the image of the Government of Tanzania” by making derogatory statements about the trophy hunting industry in emails, according to a letter they sent him. And in April, while visiting the Serengeti to film a BBC documentary, a chief park warden informed him that he had been barred from the country. (Apparently, he had made it through customs by mistake.)

Dr. Packer described the events leading to his banishment in his recently published book, Lions in the Balance: Man-Eaters, Manes, and Men with Guns. It mixes episodes of spy novel intrigue with detailed descriptions of scientific studies and PowerPoint presentations.

To read more about Packer’s work published by the University of Chicago Press, click here.

To read more about Lions in the Balance, his latest book, click here.

Add a CommentBlog: The Chicago Blog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Fiction, Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts, Books for the News, Commentary, Add a tag

Eduardo Lalo, as a review in Necessary Fiction notes, is a name familiar to very few English readers. “At the time of this review, a Google search of ‘Eduardo Lalo’ turns up very little in English—only a basic Wikipedia page. One hoping to read more about the author must brush up on one’s dusty Spanish skills.” The Cuban-born Lalo, however, began to gain more cosmopolitan acclaim with the publication of his book Simone, which won the Rómulo Gallegos International Novel Prize, an award that aims to “perpetuate and honor the work of the [titular] eminent novelist and also to stimulate the creative activity of Spanish language writers.” (The award is somewhat comparable, though much larger in scope, to the Man Booker Prize.) ” On the heels of the award, the the book’s first English language translation, by David Frye, has recently been published by the University of Chicago Press. The plot arc of the novel is complex, and the book’s narrative fealty vacillates between the subject positions of a self-educated Chinese immigrant, a jaded novelist, and the eponymous Simone.

From Necessary Fiction, which manages to condense the core of what is at stake for Lalo:

Just when we have uncomfortably settled into the doomed love story, the book takes a significant turn. Toward the end of the novel, the narrator and a novelist friend of his interrogate a visiting Spanish writer about the literature of the peninsula, and the lower quality work—in their opinion—that many Spanish publishers publish. (There may be some continental agreement to that, as Javier Márias has stated that he had no desire “to be was what they call a ‘real Spanish writer.’”) It is, at first, a strange shift. While the plot is held in abeyance, the book tries to make a larger point about the treatment of literature. In part, the point is that Puerto Rican writers have been unfairly ignored, while more maudlin and unoriginal writings from “real Spanish writers” have received outsized attention.

While the narrator obviously has significant pride in his Puerto Rico, it inevitably comes with a concomitant sense of resentment—part of the dark shadow that follows this novel sentence-by-sentence. Upon seeing the name “Colony Economy” on a carton of milk in a coffee shop, the narrator muses about how Puerto Rico’s history “overwhelms and defines” him. It is an apt lens through which to view Simone—characters who cannot quite escape the world they were born into, or the childhoods they were subjected to, a country shackled by the past and every extension of happiness undercut by sorrow. “What is left of the men and women of this country?” the narrator muses. “What remains but the coffee and the centuries, ground down and percolated, flowing through steel tubes, pouring from plastic spigots?”

To read the review in full, click here.

To read more about Simone, click here.

Add a CommentView Next 25 Posts

It’s a (normal) delusion that we all have. I used to think everyone was better than me – like phenomenally better than me. It made me sick. I would get all worked up and try to draw some amazing piece so I can be just as good as them. Turns out we’re all the same, more or less. i was just having a moment of fear, anxiety, and stress.

Wow, I really needed to read this today. Bryan Hill is articulating what I feel right now, in the midst of chasing a dream that nobody thinks is right for me. Thank you for doing Natasha justice. She’s my favorite Avenger.

God, I know this voice. I know it as depression, anxiety, and I’ll be damned if guilt (often unwarranted, I am told) isn’t an amplifier. If you’re reading the comments (and I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t; I mean, this *is* the Internet), thanks for writing this, Bryan. I’ve often felt a pull to Natasha’s chosen redemptive arc, and you express it with beautiful conviction. I’m pursuing a far-fetched dream of my own in the evenings, every day when I clock out, and I’m sure to be looking back at this from time to time.