new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 50

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

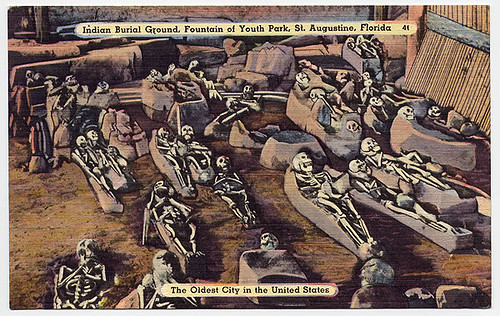

I wrote about T.D. Allman’s Finding Florida, a history of the state, and a history of the state’s fake history of itself, for the latest Bookforum. An excerpt:

“Nude face-eating cannibal?” Carl Hiassen wrote last year, when the infamous video surfaced. “Must be Miami.”

It sounds like a joke, but throw in the overpass, homeless victim, and fundamentalist drug-addict murderer, and there really are no other contenders. At least the rest of the world has some inkling of this now. As Hiassen says, explaining the Sunshine State’s endlessly inventive dysfunction has gotten easier since the 2000 presidential election. But even natives may be surprised, reading T.D. Allman’s tremendous 500-year history, Finding Florida, to learn just how much of the insanity is nothing new under the sun.

Almost a century and a quarter before Bush v. Gore, the outcome of the 1876 presidential election hinged on a Florida recount…

The rest is available in print, or to subscribers.

For Tin House’s site, I write about finding solace for the slow pace of my own novel in the writing of Donna Tartt and my friend Alexander Chee.

“Search is a deep human yearning, an ancient trope in the recorded history of human life.” Please get to know Ellen Ullman’s novelistic and critical brilliance (which I discuss at length at Salon) if you haven’t yet.

“The model I saw was that a writer was someone who sat at the table writing.” At B&N Review, I talk with writer, bartender, and NYT Mag drink columnist Rosie Schaap about her new book Drinking With Men.

I wrote about Mary McCarthy’s dissertation-worthy The Group for Bookforum’s summer Money issue. Print only, for now at least. Please let her Paris Review interview (with a young Elisabeth Sifton!) whet your appetite.

My latest New York Times Magazine columnlet draws on a passage from H.L. Mencken’s The American Language (1921) about the word “bug.”

“An Englishman,” he says, restricts its use “very rigidly to the Cimex lectularius, or common bed-bug, and hence the word has highly impolite connotations. All other crawling things he calls insects. An American of my acquaintance once greatly offended an English friend by using bug for insect. The two were playing billiards one summer evening in the Englishman’s house, and various flying things came through the window and alighted on the cloth. The American, essaying a shot, remarked that he had killed a bug with his cue. To the Englishman this seemed a slanderous reflection upon the cleanliness of his house.”

In a footnote, Mencken elaborates: “Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’ is called ‘The Golden Beetle’ in England. Twenty-five years ago an Englishman named Buggey, laboring under the odium attached to the name, had it changed to Norfolk-Howard, a compound made up of the title and family name of the Duke of Norfolk. The wits of London at once doubled his misery by adopting Norfolk-Howard as a euphemism for bed-bug.”

In a footnote, Mencken elaborates: “Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Gold Bug’ is called ‘The Golden Beetle’ in England. Twenty-five years ago an Englishman named Buggey, laboring under the odium attached to the name, had it changed to Norfolk-Howard, a compound made up of the title and family name of the Duke of Norfolk. The wits of London at once doubled his misery by adopting Norfolk-Howard as a euphemism for bed-bug.”

Even today, slang guru Jonathon Green confirmed when I asked him on Twitter, the UK “does use ‘bedbug’ but otherwise, I would say UK still mainly [uses] ‘insect.’” A British friend of mine agrees, but says of the Mencken passage, “nowadays bug has no connotations of uncleanliness, it’s just not used. The only time an English person says bug to mean insect is ‘don’t let the bedbugs bite’ and no modern British person’s ever had bedbugs, so it’s just a saying, not an insult! We know that it’s a general American term for insect, but we tend to call insects by their species, generally — fly, beetle, ladybird, etc — or, if we need a catch-all euphemism, we’ll say ‘creepy-crawly’ or in Scotland ‘beastie’ (or ‘wee beastie’).”

As the plague spreads, visitors to the UK may wish to make linguistic adjustments.

By: Maud Newton,

on 2/12/2012

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

minicolumn,

cabbies,

hackney carriage,

Culture,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

anniversaries,

charles dickens,

Published Elsewhere,

nytmag,

Add a tag

My latest New York Times Magazine mini-column is on London’s taxi drivers, who memorize 25,000 streets and 20,000 landmarks to obtain a license; they emerge from the training with a larger hippocampus. In the smaller city of his day, Charles Dickens also mastered the roads — to avoid being overcharged. But eventually, as he explains in an essay published in 1860 in All the Year Round, an interview with one man left him with “a more charitable view of the business and trials of cab-driving.”

My wife, accompanied by a servant, and our first-born, an infant, aged three months, had started, one November afternoon, to visit a relative at the other side of London. The day was misty, but when the evening came, the whole town was filled with a dense fog, as thick as soup. I gave them up at an early hour, never supposing that they would attempt to break through the black smoky barrier, and accomplish a journey of nearly nine miles. In this I was mistaken, for towards eleven o’clock the door-bell rang, and they presented themselves muffled up like stage-coachmen. The account I received was, that a four-wheeled cab had been found, that they had been three hours and a half upon the road, that the cabman had walked nearly the whole way with a lamp at the head of his horse, and that he was now outside awaiting payment.

I felt a powerful struggle going on within me. The legislature had fixed the price of cab-work at two shillings an hour, or sixpence a mile, but it had said nothing about snowstorms, fluctuations in the price of provender, or November fogs. There was no contract between my wife and the cabman, and she had not engaged him by the hour, so that, protected by the Act of Parliament, I might have sent out four-and-sixpence for the nine miles’ ride by the servant, and have closed the door securely against the driver. Actuated, perhaps, as much by curiosity, as a sense of justice, I did not do this, but ordered the man in, and gave him the dangerous permission to name his own price. He was a middle-aged driver, with a sharp nose, and when he entered the room, he placed his hat upon the floor, and seemed a little bewildered by novelty of his situation.

“If I am to, I am,” he said,” but I’d my rather leave it to you, sir.”

“This is a journey,” I replied, “hardly within the meaning of the act, and whatever you charge, I will cheerfully pay.”

“Well,” he said, with much deliberation, “I don’t think five shillin’s ought to hurt you?”

As you probably know if you encountered any news source of any kind last week, February 7 was the 200th anniversary of Dickens’ birth. In honor of the occasion, the Guardian filmed Simon Callow on Dickens’ London, the British Council sponsored a readathon, A.N. Devers

By: Maud Newton,

on 2/7/2012

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

ray bradbury,

miami herald,

plato,

twilight zone,

madeline miller,

patroclus,

robot teachers,

south florida landmarks,

Culture,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

iliad,

Published Elsewhere,

achilles,

minicolumn,

electric grandmother,

Add a tag

I’m behind on everything around here, even linking to my New York Times Magazine mini-columns. Recently I’ve written about: plans to turn the old Miami Herald building into a casino; the (partial) realization of Ray Bradbury’s dream of robot teachers; and, courtesy of Madeline Miller and Plato, The Iliad as love story between Achilles and his man Patroclus.

Bradbury’s comments about robot teachers appeared in a 1974 letter to Brian Sibley. And his short story, “I Sing the Body Electric,” about a girl and her electric grandmother, inspired one of my favorite old Twilight Zone episodes — favorite even though it gave me nightmares — and a mini-series (clip above).

By: Maud Newton,

on 12/12/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

architecture,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

catholics,

evangelicals,

Published Elsewhere,

Art & Design,

crystal cathedral,

hour of power,

philip johnson,

robert schuller,

Religion,

Culture,

Add a tag

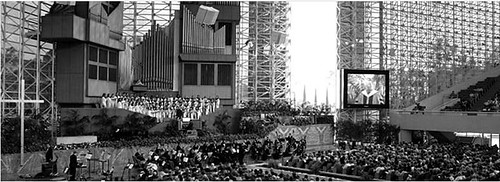

The Crystal Cathedral of “Hour of Power” fame is the subject of my latest New York Times Magazine mini-column. Not so long ago the most lavish symbol of U.S. Protestantism, the building sold in bankruptcy last month to a Catholic diocese.

Although the congregation has agreed under the terms of the deal to vacate the premises after three years, pastor Sheila Schuller Coleman, daughter of founder Robert H. Schuller, assures her flock, “lest you think that it’s too late for a miracle, I want to reassure you and remind you that it is not too late. There is still time for God to step in and rescue Crystal Cathedral Ministries.”

Bonus reading: Joseph Clarke’s “Infrastructure for Souls,” on the “parallel histories of the American megachurch [including the Crystal Cathedral] and the corporate-organizational complex.”

By: Maud Newton,

on 12/12/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

PEN,

bob dylan,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

nyt,

lucinda williams,

paul muldoon,

Published Elsewhere,

leonard cohen,

elvis costello,

christopher ricks,

paul simon,

rosanne cash,

Music,

Culture,

Add a tag

My mini-column for last week’s New York Times Magazine is on poetry and song. King David viewed them as natural companions, but these days they’re seen as distinct, unrelated arts.

Accepting Spain’s Prince of Asturias Award for Letters recently, musician and poet Leonard Cohen implicitly took David’s view. He spoke of learning a progression of six flamenco chords from a mysterious young Spaniard who soon killed himself. “It was those six chords,” Cohen said, “it was that guitar pattern that has been the basis of all my songs and all my music… Everything that you have found favorable in my songs, in my poetry are inspired by this soil.”

And he expressed unease over the honor. “Poetry comes from a place that no one commands and no one conquers. So I feel somewhat like a charlatan to accept an award for an activity which I do not command. In other words, if I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often.”

Related: Christopher Ricks, Jonathan Lethem, and Lucinda Williams on the case for Dylan as poet; PEN New England’s new prize for excellence in song lyrics, judged by Paul Simon, Elvis Costello, Rosanne Cash, Paul Muldoon, and others; The Village Voice’s jokey list of contenders for the award; and, courtesy of my friend Michael Taeckens, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison. And, just for fun, Roger Miller and Dave Hickey on Hank Williams’ hooked-up verse.

Angry birds — and especially smart, angry birds — aren’t just the subject of my latest NYT Mag mini-column. Because my mom collected and bred parrots, they’re something I’ve spent far too much time pondering.

Did you know that crows develop grudges against people and can impart them to their flocks? Or that African Greys are capable of labeling and counting objects and grasping the concept of zero? Or that birdsong appears to be in some sense grammatical? Often parrots use their powers for good, and not evil, of course. As far as we know.

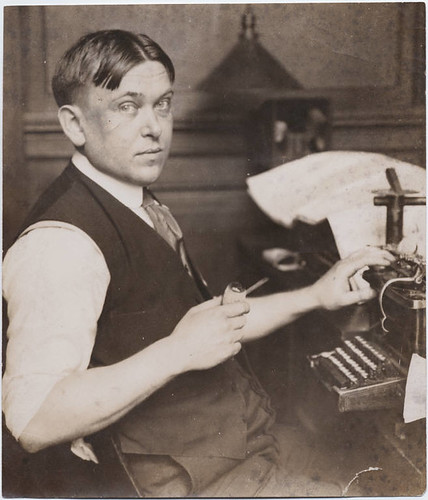

Daphne du Maurier (above), who wrote “The Birds,” about an avian apocalypse, said the idea came to her after she saw a farmer ploughing a field while seagulls dived above him, and she imagined the birds “becoming hostile and attacking.” Evidently she disapproved of Hitchcock’s also harrowing, more famous adaptation.

If you click through to the BBC interview, you can watch her talking about her life and work for almost 50 minutes. The clip opens at her typewriter, “the standard ‘the author at work’ establishing shot except for du Maurier’s super-strong finger-punching technique on the keys.” Though du Maurier made her living as a writer, she also dabbled in painting.

By: Maud Newton,

on 11/21/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Neuroses,

nytmag,

sandstorm,

Culture,

texas,

great depression,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

the grapes of wrath,

dust bowl,

woody guthrie,

steinbeck,

Published Elsewhere,

drought,

Add a tag

Similarities between our time and the Great Depression era are extending beyond the fiscal crisis.

My latest New York Times Magazine mini-column looks at a sandstorm, “Steinbeck-ish in its arrival,” that rolled through Lubbock, Texas last month, as a harbinger of a possible impending (and permanent) Southwestern Dust-Bowlification. “I expected at any moment to see a line of Model Ts coming through headed to California,” a city councilman said. “It really did look like pictures I had seen of the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.”

See (and hear) also a tour of Grapes of Wrath country as of 2009 and Woody Guthrie’s “Talking Dust Bowl Blues” (above).

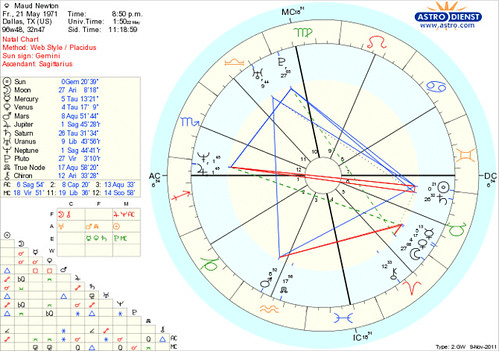

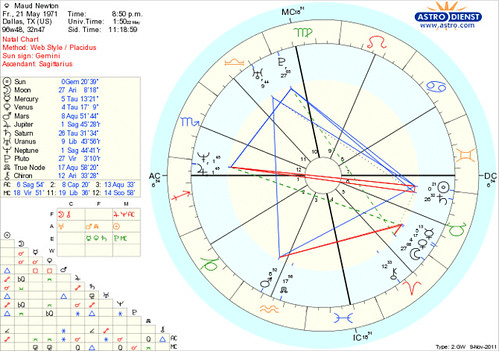

The first installment of my new microcolumn, “The Historical Record,” ran in The New York Times Magazine on Sunday alongside some other quickies, including Lizzie Skurnick’s brilliant (and useful!) “That Should Be A Word.” This one concerns astrology, from Chaucer to Susan Miller.

A friend who, like me, is drawn to the stars, says astrology shouldn’t and possibly doesn’t work at all, that it’s just really easy for those of us who are attracted to and adept with metaphor to stretch the system to fit reality. I don’t disagree with her, exactly — of course I don’t, I’m a Gemini — but it doesn’t take more than a drink or two with friends before I’m pulling out my iPhone to look up their charts and their lovers’ charts and to ponder their synastry…

As I mentioned in the columnlet, Miller and I talked about Occupy Wall Street, which she attributes to a square between Uranus and Pluto that will recur into 2015; she believes the demonstrations will continue at least until then. (There was also a strong Uranus-Pluto aspect during the the Civil Rights Era, she points out. And the last time Pluto was in Capricorn, as it is now, the American Revolution happened.) “The universe always pushes us back onto the rails,” she says, predicting less government gridlock and a better housing market next year.

Like most of her readers, I became aware of Miller online, where the zodiac is big business these days. Many sites offer “personalized” computer-generated reports, round-the-clock transit predictions, and even phone consultations; Miller is more like a magazine columnist, posting general monthly forecasts for each star sign at her site, Astrology Zone. I asked her what she thinks about the explosion of Internet astrology.

“You need to know the provenance of the advice,” she said. “A lot of Internet advice is unsigned, which means there’s no yardstick.” She’s heard of many sites that “hire college girls — ‘A’ students in English — who have beautiful writing skills but no astrological background.”

What surprised me most was her response to my mention of Liz Greene, a Jungian analyst-astrologer I like whose “psychological horoscopes” are sold at Astro.com. “I don’t do psychological astrology,” Miller said. “I am very practical. I don’t presume to tell you what you’re thinking or feeling.” (But that’s my favorite part!)

My (waterless) chart, if you’re curious:

I reviewed Joan Didion’s Blue Nights, which is both gorgeous and terrible (terrible in the King James sense of awesome, dreadful, and fearsome, like when God appears to Moses).

In 2003′s Where I Was From, Joan Didion tells of a long wagon journey on which her great-great-grandmother buried a child, gave birth to another, contracted mountain fever twice, and sewed a quilt, “a blinding and pointless compaction of stitches,” that she must have finished en route, “somewhere in the wilderness of her own grief and illness, and just kept on stitching.” Throughout the book, Didion ruminates on her female forbears, women “pragmatic and in their deepest instincts clinically radical, given to breaking clean with everyone and everything they knew,” even their own dead babies.

It was Didion’s adopted daughter Quintana, at age five or six, who first made all this heredity start to seem remote. And if the author harbored any lingering doubt about whether she shared her ancestors’ breaking-clean tendencies, the shattering effect of Quintana’s death in 2005, at age 39, must have swept it away. In her new memoir, Blue Nights, about life before and after the loss of her daughter, Didion writes, “When we talk about mortality, we are talking about our children.”

You can read the full review at B&N Review, watch Didion reading from the book in a Daily Beast video, and listen to her talk about it at NPR.

Previously: Didion on psychiatric trends and diagnoses; the specter of the unanswered letter; “I didn’t want to be a writer. I wanted to be an actress”; and a short but revealing 1970 TV interview with Tom Brokaw.

In the food issue of the New York Times Magazine, out this weekend, writers answer various questions. Mine was “How does rattlesnake taste?” Obviously I roped Dana, Max, and Nick in, and obviously we intended to follow (to the extent possible) Harry Crews’ instructions.

Tracking down a diamondback in New York City proved impossible, even after I took to Ask Metafilter. Unlike Crews’, our snake arrived in the mail, skinned and gutted, stripped of head and tail. Coiled on the cutting-board, it looked like a garden hose made of filleted haddock.

And as we took a cleaver to it, laboriously hacking it into one-inch slices, the spine was so thick and resistant to cutting, I found myself wondering if hedge clippers would be more effective, or at least less likely to result in someone losing a finger.

Although Crews warned against overcooking, he didn’t provide concrete guidance on timing. (He always said writers should be prepared to take work as short-order cooks, so perhaps it was presumed we’d know intuitively.) Within three minutes the first batch was dry and crunchy and inedible, the breading shriveled against the bone, the lean meat evidently having been boiled completely away.

On second try, the fritters (“steaks,” Crews calls them, but this native Texan just can’t use that term to encompass such stingy game) were juicier. The flesh was still hard to locate, though, trapped as it was in thick, slanted Vs to each side of the spiny vertebrae up top. (Maybe I overcooked it all and have unfairly maligned the dish.)

As Dana says, “God bless Harry Crews (one of my favorite authors, and one of the many subjects Maud and I first bonded over when we met nearly nine years ago) but I’m not sure I’ll be taking any food or beverage recommendations from him in the future.” We ate the snake with cornbread and fried okra, and a salad for the veneer of health, and we followed it up with her amazing berry pie.

You can read about the actual taste of the snake — and other ways to prepare it — over at the Times Ma

By: Maud Newton,

on 7/28/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

junot diaz,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

sherman alexi,

karen russell,

geoff dyer,

emma garman,

donna tartt,

Chris Adrian,

john colapinto,

siri hustvedt,

tea obrecht,

Add a tag

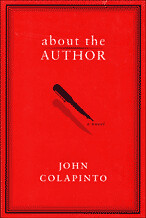

The Daily Beast asked some writers — Donna Tartt, Junot Díaz, Chris Adrian, Geoff Dyer, Karen Russell, Sherman Alexie, Siri Hustvedt, Darin Strauss, Téa Obreht, Kathryn Stockett, Alexandra Fuller, Anne Enright, Elisabeth Kostova, Alexander McCall Smith, and me — about our favorite summer books.

The Daily Beast asked some writers — Donna Tartt, Junot Díaz, Chris Adrian, Geoff Dyer, Karen Russell, Sherman Alexie, Siri Hustvedt, Darin Strauss, Téa Obreht, Kathryn Stockett, Alexandra Fuller, Anne Enright, Elisabeth Kostova, Alexander McCall Smith, and me — about our favorite summer books.

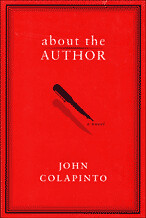

Mine is John Colapinto’s first (and, so far, only) novel, About the Author. What I said:

I read John Colapinto’s hilarious, propulsive, and gorgeously written About the Author in a single day almost exactly eight years ago, before the rise, demise, and resurrection of James Frey, when I knew next to nothing about publishing but had great expertise in planning to write and not writing. The novel’s narrator, Cal Cunningham, has also perfected this skill. A supposed wordsmith, he spends his days shelving books at a big midtown bookstore, nights going from bar to bar picking up girls and getting laid, and Sunday mornings filling his dull law student roommate in on his escapades. Our hero’s sense of superiority is shattered when he discovers that the roommate hasn’t been locked in his room typing tedious legal briefs but working on a novel, one that’s actually good, one that sounds suspiciously like Cunningham’s own life, so much so that when the roommate dies unexpectedly… Well, I’ve already said too much, but it’s a remarkable book, a confessional literary thriller that makes you care about its plagiarist narrator even as it reveals him to be a coward and a liar and satirizes the publishing and media world that exalts him.

I’ve been blogging so long, I can point exactly to when I first read About the Author, a gift from Emma early in our friendship. (I didn’t know then that the novel took Colapinto thirteen years to write. No judgment here.)

Head over to the Daily Beast for the other picks.

My contribution to the “Why’s This So Good?” series — a collaboration between Longreads, Alexis Madrigal, and Nieman Storyboard’s Andrea Pitzer designed to explore “what makes classic narrative nonfiction stories worth reading” — is about Raymond Chandler’s 1945 “Writers in Hollywood,” a scathing attack on the motion picture industry.

Candler “brought to bear on his subject all the fury and surprising insights of the novelist who wrote ‘The Big Sleep,’ the gimlet-eyed practicality of the storyteller whose first publications were for pulp magazines, and the staggering self-absorption of the depressive alcoholic.” And the critique isn’t just a dusty object of curiosity from the vaults; it’s relevant now.

In the heyday of the Hollywood novelist-screenwriter, a slew of literary talents – Chandler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, Dorothy Parker and Aldous Huxley, to name just a few – did time writing film scripts because they were easy money. Now, in the new narrative TV landscape, it’s cable companies that are signing novelists and memoirists in droves. Jonathan Ames, Jennifer Egan, Sam Lipsyte, Sloane Crosley, Salman Rushdie, Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman are just a few recent hires. Given that fiction writers like Richard Price and George Pelacanos helped shape “The Wire,” arguably the most interesting story of our time, the focus on novelists makes a certain amount of sense. But how much creative control will they have? And will cable TV, too, eventually become too rigid to allow innovation?

You can read the rest, along with prior installments from Alexis Madrigal, Radhika Jones, Carl Zimmer, and Chris Jones, over at the Nieman Storyboard site.

Previously Ten novels and short stories that would make good movies (at IFC) and notes following The Wire season 5 premiere.

At the Awl, Kate Christensen and I discuss her latest novel, The Astral, and many other things, including cheating hearts, failed marriages, bad therapy, male muses, inner dicks, and (briefly) her next book, Gin on the Lanai.

“I write about people wrestling with various internal conflicts in ways that ripple outwards and cause more external conflicts,” she says. “Repressed, obedient, ‘good-citizen’ characters interest me very little because there’s little possibility for change in them. I’m a very old-fashioned writer. Change is what I’m after… Flux is exciting; struggle and discord and trouble fascinate me.”

By: Maud Newton,

on 6/11/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Selected Press,

dorothy allison,

the paris review,

emma straub,

lorin stein,

thessaly la force,

anna holmes,

granta,

hamish robertson,

john jeremiah sullivan,

kat stoeffel,

longreads,

mark armstrong,

sadie stein,

Personal,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

eudora welty,

new york times magazine,

Add a tag

Mark Armstrong of Longreads posts his top essays and articles over at Mother Jones each week, and this time around I’m his “Featured Longreader.” Here’s some of what I’ve been reading recently:

A Disney trip with kids meets lots of furtive weed smoking in John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Rough Guide to Disney World. “It was a double hallucination,” he says. “You were hallucinating inside of Walter Disney’s hallucination. That’s what he wanted.” Already an official #longreads pick, I know, but: it’s so, so good and only gets better as it goes.

I’ve also been revisiting Eudora Welty’s fiction in preparation for a Granta event [held at the New School last night]. “Why I Live at the P.O.” and “Petrified Man” are two of her most beloved stories, and with good reason: they’re funny and relentless and so accurately and minutely observed. Returning to them, I realized what an influence she must have had on Dorothy Allison (whose Bastard Out of Carolina, a #longlongread, I also recommend). Then I confirmed it. “I was seduced by Eudora Welty,” Allison wrote in 2005, though “I had every reason to distrust her, as I had distrusted Faulkner—both of them products of the middle-class South I disdained.”

To round out this unexpectedly southern round-up, for anyone who missed it last week, I recommend my friend Anna Holmes’ essay on the female Freedom Riders of the Civil Rights movement. One, a factory worker and mother of two traveling after a miscarriage, refused to give up her seat to a white couple and kicked a deputy in the groin when he tried to make her.

I spend so little time around here these days, I forgot to mention my inclusion in Paper Magazine’s Lit It Crowd. I love the photo; all my companions — Thessaly LaForce, Sadie Stein, Emma Straub, and Hamish Robertson — look dead sexy (which they are), while I’m off to the side, hands folded, gazing skyward and seemingly clucking like a delighted schoolmarm/auntie.

It’s a group, Lorin Stein said, “lousy with Parisians”: Thessaly and Sadie are editors and writers at The Paris Review Daily, and Emma and I are contributors. News of Thessaly’s upcoming departure for the Iowa Writers Workshop and that The New Yorker’s Deirdre Foley-Mendelssohn will be taking over prompted The New York Observer’s Kat Stoeffel to note the Paper feature, in “Les Filles du Blog,” and to observe that “Although many intellectual and literary magazines have come under scrutiny lately for a lack of female bylines,&rd

By: Maud Newton,

on 2/14/2011

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

james hynes,

chang rae lee,

good sex in fiction,

james carroll,

jennifer gilmore,

jillian weise,

maggie pouncey,

Personal,

Reviewed/Discussed Elsewhere,

salon,

joshua ferris,

jonathan franzen,

Add a tag

Salon chose eight novel excerpts for its first Good Sex in Fiction Contest, and asked Louis Bayard, Walter Kirn, Laura Miller, and me to judge and discuss them. I ranked the Franzen highest, and also outed myself as a total pervert.

The problem with these excerpts is — and I didn’t entirely realize this until I started reading for the contest — that the sex I respond to most in fiction is really fucked-up. It’s definitely not that I want to experience the anonymous sexual assaults of Nicholson Baker’s The Fermata (though I confess, I did think that book was hot, in its autistic way), or get involved with a porn-obsessed televangelist as in A.L. Kennedy’s Original Bliss, or abduct a man and use him as my sex slave, as in Rupert Thomson’s The Book of Revelation, but those stories stay with me because they reveal something incredibly dark and twisted and, to me, true about desire and obsession. I like fiction, whatever the subject, that exposes the surprising longings its characters harbor in their heart of hearts. Mary Gaitskill’s “The Other Place,” in the latest New Yorker, is a perfect example, though it’s not actually about sex at all.

You can read the contenders, the winner (from my pal James Hynes’ Next), and our discussion over at Salon. For more distorted sexuality in fiction recommendations, see The Paris Review Daily’s latest advice column. I also love my friend Alexander Chee’s fabulously disturbing and complex Edinburgh. And finally, I re-recommend James Hynes’ piece on “The Dreamlife of Rupert Thomson.”

My friend Misha Angrist, a former geneticist and the author of Here is a Human Being At the Dawn of Personal Genomics, answers some of my questions about DNA research at The Awl.

Holy crap, Misha, you’re making your entire genome public! Are you nervous?

It’s already done. All of my data are here. Frankly I don’t think anything in my DNA could be as embarrassing as this kelly green shirt that continues to taunt me from the interwebs.

I spend a lot of time worrying about the long-term consequences of opening the Pandora’s box just by joining 23andMe.

Hmmm. What is it you’re worried about exactly?

Well, in addition to being an enthusiastic neurotic, I’m a hypochondriac with health problems, and I guess I’m anxious that I won’t be able to get insurance coverage in my old age, and I’ll end up being yelled at and bossed around in some grannies’ ward with rows and rows of beds, like in Memento Mori

.

Here Is a Human Being

includes some pretty sobering stories of insurance companies — and even the military — booting people because they’re at high risk for certain genetic conditions.

True, although I suspect that those types of stories are rare. But even if they’re not, I believe that one way of combating/preempting that sort of behavior is by having a cohort of people putting it all out there and seeing what happens. I am fairly well convinced that if an insurer or employer used a Personal Genome Project participant’s data to discriminate against him/her, the personal genomics hive would raise holy hell and quickly create a PR nightmare for the perpetrator.

Ah, so participation is actually a kind of insurance of its own! Where do I sign up?

Yeah, if you fuck with me, then you fuck with all of the public genomes and arguably the entire biomedical research enterprise.

More here, and we continue the conversation at McNally Jackson tonight, at 7 p.m. Join us if you’re free.

My favorite “new” book of the year will surprise no one. It’s the Autobiography of Mark Twain, and I wrote about it for Salon, where there are also best of 2010 contributions from my friends Laura Miller and Laura Lippman, and from other writers, including David Grann, Ted Conover, George Pelecanos, Dave Eggers, Elizabeth Kolbert, Anthony Shadid, James Fallows, and Rebecca Traister.

I’ve also written about favorite books — particularly an old one I discovered this year — for The Millions’ always-outstanding Year in Reading. I’ll add the link when that piece goes up.

While I’m aggregating things from other places: recently I’ve started making more use of Tumblr; I really like the feeling of community and all the pretty pictures. And not long ago I talked with Kate Donnelly about the incredibly exciting spot where I’ve spent most of my free time for the past twelve months: my desk. That’s a photo above and if you’re interested you can read more about it and its contents at From Your Desks.

This year I also kept a Paris Review Culture Diary (part two), wrote an ode to the (enchanted) Biltmore Hotel for Oxford American, reviewed the new Muriel Spark biography, and now worship her and her writing. I also fell in love with E.B. White’s One Man’s Meat and Kingsley Amis’ Everyday Drinking. I curated the Girls Write Now series featuring the talented Dolen Perkins-Valdez, Nami Mun, Marie Mockett, Lizzie Skurnick, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi, and I interviewed Rosecrans Baldwin about his accomplished first novel.

I realized I was writing two books rather than one, and focused on the first one, and read a previously-unheard excerpt from it. I started writing for The Awl about my obsession with Sarah Palin and far-out evangelicals generally, and I watched the first episode of Palin’s Alaska with my pal D.E. Rasso and we recapped it for your amusement. And though I haven’t written about this in any detail, I joined 23andme, found out more about my grandfather’s (alleg

I took a hiatus from my reviewing hiatus to write about Adam Levin’s The Instructions for B&N Review. The book runs a little over a thousand pages; by the end, I would gladly have signed on for another thousand. Here’s an excerpt:

Adam Levin’s dark, funny, and deeply provocative first novel, The Instructions, comprises the scriptures of one Gurion ben-Judah Maccabee, an impossibly articulate ten-year old who might or might not be the messiah. When I say “impossibly,” I do mean impossibly, but Gurion is no cutesy child hero. He shares with Oskar Snell — the young, tambourine-playing pacifist vegan of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close — a fixation on the horrors of the past, and like Snell’s his story is propelled by a series of unlikely, seemingly symbolic coincidences. Here, though, there is no redemption, only confusion and violence — an indictment of tribe mentality, and of the concept of being “chosen.”

Gurion’s scholarly erudition is so staggering, so monumentally over-the-top, that the accusation of its implausibility is embedded in the book itself. A footnote excerpts a letter from Philip Roth (his fictional counterpart, anyway), who misreads fan mail from Gurion as an adult’s “terrifically cruel and on point” mimicry of “recent so-called Jewish wunderkind authors.” Roth urges him to stop “writing from the unconvincing POV of a boy-genius whose name suggests a messianic fate” and instead to adopt the more realistic perspective of a man remembering his childhood “as a time when he, like so many of us, suspected that he was the messiah.”

Even at five years old, we are told, the boy asked scriptural questions so complex that his mentor, a rabbinical scholar, was moved to transcribe their conversations. No doubt the allegorical touchstone is different for Jewish readers, but for this fundamentalist-raised gentile the obvious echo is of Jesus’ three-day debate, at age twelve, that left Jerusalem’s temple elders astonished. (Luke 2:46-47) At times, like the fictional Roth, I struggled with Gurion’s voice — with the high diction, and the essaylets and other postmodern flourishes — but Levin has an uncanny facility for blending sympathy and satire, for making us care about his charming but dubious hero and for infusing life into this alternate, slightly fantastical reality that’s very much like our own. The Instructions recalls both the real Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, in which aviation hero and Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindberg defeats FDR on an isolationist platform and winds up in the White House, and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slapstick, in which members of the Church of Jesus Christ, Kidnapped are required to “spend every waking hour” trying to find their savior, who was “kidnapped by the Forces of Evil” at the second coming. And, like Roth’s and Vonnegut’s, Levin’s flights of fancy are placed in service of a deadly serious project. Not only is he, as he recently told The Chicago Tribune, having “a conversation with Jewish literature,” he’s illustrating, in a wholly original way, exactly what sort of catastrophe results when fervent religious conviction meets brute force.

You can read the rest here. See also

My review of Martin Stannard’s Muriel Spark biography appears at Barnes & Noble Review today. One of the things that struck me while reading is just how easily Spark — one of the finest and funniest novelists of the last century, or of any century — could have continued to write poetry and criticism and not tried her hand at fiction at all.

She wrote her first story at thirty-three, almost by accident; she needed money and the Observer was sponsoring a contest. After publishing her first novel at thirty-nine, though, she completed the next few books astonishingly quickly, at half-year intervals, as though some part of her mind had been readying itself for the challenge.

Despite its sprawl, Stannard’s biography is a fascinating read for Spark fans. And if you haven’t read Spark yet, please get cracking. I recommend starting with The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, The Girls of Slender Means, or my personal favorite, Memento Mori. Or maybe with her first book, The Comforters, or her last, The Finishing School… Just plunge in; it’s hard to go wrong.

Now that my thoughts are in the can, I look forward to reading The New Yorker’s recent Spark appreciation, and Dwight Garner’s review for yesterday’s New York Times. Also worth a read: James Wood on Spark’s omniscience, Brock Clarke on her ruthless authorial manipulation.

My appreciation of Brian Dillon’s The Hypochondriacs is up at NPR. If you have health problems, or worry that you have health problems, or both, you should read this book.

My appreciation of Brian Dillon’s The Hypochondriacs is up at NPR. If you have health problems, or worry that you have health problems, or both, you should read this book.

People who never get sick might enjoy it, too — if only for the opportunity to feel superior while jogging around the park in the snow — but I wouldn’t know about that.

An excerpt of my reaction:

I spent so much of my childhood sick, worried about getting sick, or pretending to be sick that these three states of being blurred together in my mind. The confusion persists; now a documented sufferer of autoimmune disease — and an undocumented sufferer of a no-doubt-fatal disorder currently manifesting as side pain — I am uncertain when to take a sick day or visit the doctor, and whatever course I decide on is almost always wrong. Yes, I belong to that most exasperating class of neurotics: hypochondriacs with health problems, the subject of Brian Dillon’s sympathetic, perceptive and often absurdly funny The Hypochondriacs.

Until the 19th century, morbid fear of illness was seen as only one symptom of hypochondria, which doctors treated as an organic disease, although scientific explanations varied. In one era, it was a digestive problem, in another an abdominal issue, and later a disorder linked with melancholia and distributed through the entire body. More importantly for Dillon’s purposes, hypochondria, which often has a physical component, provides a reason for those with intellectual or creative temperaments to sequester themselves from the world and pursue their thinking or their art.

Dillon is an unusually dexterous writer. Each of his slim chapters focuses on a different artist or thinker, and each fully evokes the subject’s fears and afflictions, showing how they’re reflected in his or her life’s work.

You can read the rest here, and an excerpt from the book here.

See also Daphne Merkin’s review for Bookforum and Laura Miller’s for Salon, Hermione Lee on bed rest and Virginia Woolf, Sarah Manguso’s The Two Kinds of Decay (and her rejection of the idea that suffering begets art), Brian Dillon’s Book Notes for Largehearted Boy, and an old post of mine about being a hypochondriac with health issues.

View Next 24 Posts