Opening the morning paper or browsing the web, routine actions for us all, rarely if ever shake our fundamental beliefs about the world. If we assume a naïve, reflective state of mind, however, reading newspapers and surfing the web offer us quite a different experience: they provide us with a glimpse into the kaleidoscopic nature of the modern era that can be quite irritating.

The post The quest for order in modern society appeared first on OUPblog.

When I began reading The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage by Sydney Padua, I did something I usually don’t do. I posted how great the book is and how everyone needed to, right then and there, request a copy from the library or buy one of their own. Now that I have actually finished it, I still stand by that assertion.

When I began reading The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage by Sydney Padua, I did something I usually don’t do. I posted how great the book is and how everyone needed to, right then and there, request a copy from the library or buy one of their own. Now that I have actually finished it, I still stand by that assertion.

The book is a graphic novel like no other I have read (which is more than some and less than a good many). Sure the stories are told with great black and white drawings, some of them very detailed like the visual explanation in the appendix of how the Analytical Engine would have worked if it were ever built. Wait, appendix? A graphic novel with an appendix? Yup. And that is just one way this book is different. It also has footnotes and endnotes. In fact, the graphic part of it is almost beside the point. To be sure, the graphics tell a story, but the real action, where all the fun and humor is, is in the footnotes and endnotes. Crazy!

Padua has clearly done extensive research, she even got a scholarly slam dunk by finding a letter in an obscure archive somewhere that settled a dispute about just how much Ada Lovelace had to do with Babbage and maths and the Analytical Engine and computer programming (a lot!). Booyah! And Padua clearly enjoys her subjects as well, expressing great knowledge and affection for them and all their quirks and foibles.

Since Lovelace died when was 36 and the Analytical Engine was never built, Padua takes liberties with the story, moving the pair to a pocket universe in which Ada lives and the Engine is built. Still, she remains true to certain biographical events, even quoting them directly at times in the stories. When she veers far off course there is a handy footnote to tell us so.

I say stories because that is what these are, short stories in graphic form. So we have a story about the Person from Porlock, one in which Lovelace and Babbage meet Queen Victoria and give her a demonstration of the Analytical Engine. Except the Engine crashes, (even when computers were only theoretical there were provisions for what to do when they crashed) and Ada runs off to fix it and save the day while Babbage bores the Queen with stories about how great he is. The Queen, not understanding why the Engine is a useful thing is losing interest until Lovelace’s programming produces a picture of a cat. Heh. Cats and computers belong together apparently. We meet George Boole whose Boolean logic will be familiar to both computer geeks and librarians. And there are often hilarious run-ins with many other famous personages.

One that a good many of you will be familiar with is George Eliot. She and Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Thomas Carlyle and others are summoned for a “mandatory spell-check” of their most recent manuscripts. Lovelace really did theorize that the Analytical Engine should be able to analyze symbols as well as crunch numbers. Eliot’s manuscript gets fed into the Engine but it being her only copy she immediately changes her mind. Thus follows a long pursuit through the workings of the Engine to try and get the manuscript back. But horror of horrors, the Engine uses “destructive analysis” and the manuscript gets ripped to shreds! And then it crashes the Engine. The huge joke at the end of this is that there had been a tussle at the beginning and Eliot and Carlyle got their manuscripts mixed up and it is actually Carlyle’s manuscript on the history of the French Revolution that is destroyed. In real life Carlyle’s manuscript was indeed destroyed. He had given it to his friend John Stewart Mill to read. The only copy. Mill left it sitting out and the servants thought it was waste paper and used it for starting fires. Oops. Carlyle had to rewrite the who book, but personally, from what I have actually read about the incident in other places, it was probably for the best because the rewrite by accounts was better than the original. Still, Carlyle was devastated and I don’t remember if he and Mill continued to be friends afterwards.

Anyway, this is a right fun book. Babbage and Lovelace were real characters even before they were fictionalized in a pocket universe. If you would like a taste of the book including a few stories that didn’t make it in, there is a website! The Science Museum of London also built Babbage’s Difference Engine, the precursor to the Analytical Engine, in 1991 and because of the magic of the internet, you can watch a video demonstration:

Is that thing ever loud!

If you are looking for something fun, geeky, madcap and sometimes just plain silly, you can’t go wrong with The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage.

Filed under:

Books,

Graphic Novels,

Reviews Tagged:

Ada Lovelace,

Charles Babbage,

George Eliot,

madcap adventures,

Thomas Carlyle

By James Secord

We tend to think of ‘science’ and ‘literature’ in radically different ways. The distinction isn’t just about genre – since ancient times writing has had a variety of aims and styles, expressed in different generic forms: epics, textbooks, lyrics, recipes, epigraphs, and so forth. It’s the sharp binary divide that’s striking and relatively new. An article in Nature and a great novel are taken to belong to different worlds of prose. In science, the writing is assumed to be clear and concise, with the author speaking directly to the reader about discoveries in nature. In literature, the discoveries might be said to inhere in the use of language itself. Narrative sophistication and rhetorical subtlety are prized.

This contrast between scientific and literary prose has its roots in the nineteenth century. In 1822 the essayist Thomas De Quincey broached a distinction between the ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power.’ As De Quincey later explained, ‘the function of the first is to teach; the function of the second is to move.’ The literature of knowledge, he wrote, is left behind by advances in understanding, so that even Isaac Newton’s Principia has no more lasting literary qualities than a cookbook. The literature of power, on the other hand, lasts forever and draws out the deepest feelings that make us human.

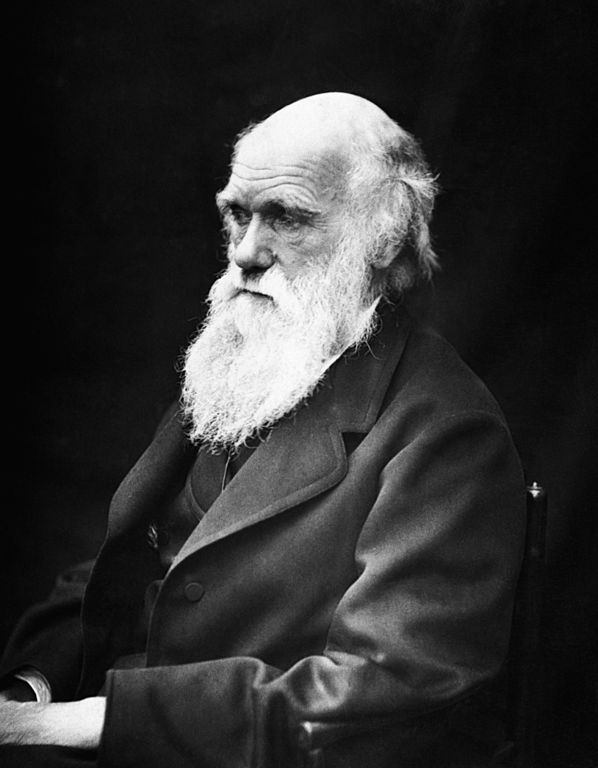

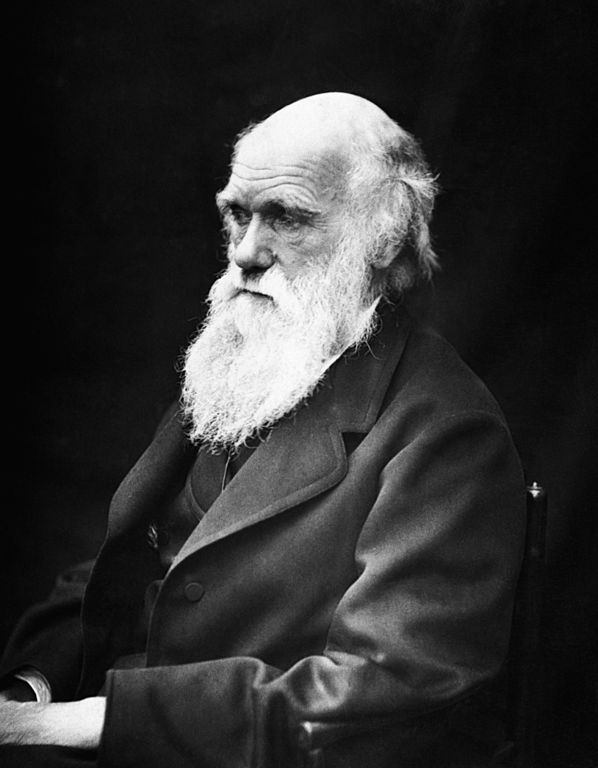

The effect of this division (which does justice neither to cookbooks nor the Principia) is pervasive. Although the literary canon has been widely challenged, the university and school curriculum remains overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of key authors and texts. Only the most naive student assumes that the author of a novel speaks directly through the narrator; but that is routinely taken for granted when scientific works are being discussed. The one nineteenth-century science book that is regularly accorded a close reading is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). A number of distinguished critics have followed Gillian Beer’s Darwin’s Plots in attending to the narrative structures and rhetorical strategies of other non-fiction works – but surprisingly few.

It is easy to forget that De Quincey was arguing a case, not stating the obvious. A contrast between ‘the literature of knowledge’ and ‘the literature of power’ was not commonly accepted when he wrote; in the era of revolution and reform, knowledge was power. The early nineteenth century witnessed remarkable experiments in literary form in all fields. Among the most distinguished (and rhetorically sophisticated) was a series of reflective works on the sciences, from the chemist Humphry Davy’s visionary Consolations in Travel (1830) to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33). They were satirised to great effect in Thomas Carlyle’s bizarre scientific philosophy of clothes, Sartor Resartus (1833-34).

These works imagined new worlds of knowledge, helping readers to come to terms with unprecedented economic, social, and cultural change. They are anything but straightforward expositions or outdated ‘popularisations’, and deserve to be widely read in our own era of transformation. Like the best science books today, they are works in the literature of power.

James Secord is Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project, and a fellow of Christ’s College. His research and teaching is on the history of science from the late eighteenth century to the present. He is the author of the recently published Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post When science stopped being literature appeared first on OUPblog.

The most amazing thing arrived in my email inbox today: the syllabus for my next library class with all of the reading assignments included. The class doesn’t start until next Monday. This is a first and a happy surprise. I’ve never had this particular professor before but I love her already. The class, collection development, has gobs of reading but since I have it all ahead of time I can get a jump on things and not rush to try to cram it all in early next week. There will also be four assignments, two of them group projects. I’m not thrilled about that but I had such a good group experience in my last class that I am not dreading it for once. I am so not ready to think about school again yet but I guess I have to. Sigh.

Before the intrusion of my class syllabus I was debating whether to write about finishing Sappho or being panicked over embarking on Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus. I think I will go with the panic and save Sappho for tomorrow when, presumably, I will be calmer.

Because I don’t know anything about Sartor Resartus I decided that reading the introduction of my Oxford edition would be a good idea; I could get some background and find out what to expect. Usually reading introductions before the book itself is a bad idea because they tend to give everything away and pardon me if I still like to read a classic and be surprised by the story. In this case, there is nothing to give away because the book has no real plot per se. What the introduction has done, however, is terrify me.

Sartor Resartus is going to be a weird and difficult book and I am concerned I am not going to “get it.” Even the introduction left me scratching my head at times and I hope that is just because I have not read the book yet. Still, as I prepare to embark on the book, I find myself wondering what the heck I was thinking. I’ve been wanting to read the book for some time because Emerson and Carlyle were friends, Carlyle was important, and I have run across references to the book in various other books. Amateur Reader’s Scottish Literature Challenge seemed the perfect opportunity to slip it into the reading lineup.

I think I must be a little crazy for deciding to read this book. My consolation is that Amateur Reader has read it and survived and might be reading it again for this challenge. I therefore am not alone in the undertaking. At this point, that is no small comfort.

Wish me luck. I will try to report regularly from the Carlylean front lines.

Filed under:

Books,

Challenges,

Library Tagged:

Thomas Carlyle

When I began reading

When I began reading