I found this from Cynthia Reeg's blog. Isn't it so great to find that your work has made a difference. Just so wonderful. Cindy said,

I found this from Cynthia Reeg's blog. Isn't it so great to find that your work has made a difference. Just so wonderful. Cindy said,

"Hey, I had a really nice thank you note today from a mom who bought a copy of DOGGIE DAY CAMP. When she shared it with her stepson, who was struggling a bit recognizing adverbs, Bubba's story seemed to flip the adverbial light on for him."

So great work Cindy. Oh, I hope he liked the pictures too.

Hip-hip-hooray for all THE PET GRAMMAR PARADE critters! Their mission is to make learning fun for kids-- KITTY KERPLUNKING and HAMSTER HOLIDAYS.

Check out these online grammar games for more grammar fun:

Fun Brain Grammar Gorillas

Grammar Blast from Houghton Mifflin

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: genre, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

Blog: Kit Grady's Blogs (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: fun, learning, Dogs, guardian angel publishing, children's picture book, reading. Houghton Mifflin, Doggie Day Care, Grammer, Hamster Holidays, Kit Grady. Cynthia Reeg, Add a tag

Blog: Time Machine, Three Trips: Where Would You Go? (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Practice, Two, yes, zwei, learning, character, Characters, in, mean, meanings, Germany, memory, greetings, german, no, grammer, greeting, country, flag, Offbeat, lesson, learn, Deutsch, Deutschland, lektion, maybe, memorise, practical, Add a tag

In the first lesson we covered how to say “Hello, how are you?” and “What is your name?” in German. In this lesson we will look at possible answers to general questions. Phrases in brackets are the pronunciation of the adjacent word. NOTE: In German you may come across an awkward character (ß) it may look like the letter B but actually represents a double s. But this character is now only used in special circumstances. For the sake of this lesson we will use ss instead of ß so you don’t get confused.

The most simple of answers are “Yes” and “No”. Which in German are “Ja” (Ya) and “Nein” (nine).

Out loud or in your head say “Yes” and then “Ja”. Repeat this three times. Do the same with “No” and “Nein”.

If your not sure how to answer something I suggest three phrases. “Maybe” - “Vielleicht” (vee-liked), “I don’t know.” - “Ich weiss nicht.” (Ick vise nickt) or “I don’t understand.” - “Ich vestehe nicht.” (Ick ver-shter-hir nickt). Now these are slightly harder phrases to learn if you are not yet familiar with German. Start by revising “Maybe” and “Vielleicht” over in your head.

It should become clear by looking at the other two phrases that “Ich” means “I”. Also you might have been able to tell that “nicht” is “not”. We have “I do not know.” and “I do not understand”. In German, however, they literally say “I know not.” or “I understand not.”. Once you know “Ich” and “nicht” these phrases should become easier to learn.

All you have to learn now is “weiss” and “vestehe”. “Weiss” meaning “know” and “vestehe” meaning “understand”. Write these words down if this is hard to memorise and use this to revise at various points during the day.

Remember to try and practice these phrases with a partner for more practical learning. Thank-you for reading my article and hopefully you can catch the next lesson.

Add a CommentBlog: Justine Larbalestier (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Bloggery, young adult literature, writers, fans, genre, Writing & Publishing, Cons & Other Gatherings, Words & Language, Writing & Publishing, genre, Cons & Other Gatherings, Words & Language, Add a tag

Thanks for all the deeply smart and thoughtful comments to yesterday’s question. You lot are awesome.

Youse lot have gotten me thinking muchly on the topic. On the one hand, I am a fan of many writers I’ve never met, like, Denise Mina, Meg Cabot, Geraldine McCaughrean, Walter Mosley, Megan Whalen Turner, Peter Temple and would probably embarrass myself by breathless gushing all over them if we were ever to meet. On the other hand, I’m a working writer who knows a lot of working writers and knows that we’re not particularly different from everyone else. (Well, except for Maureen Johnson . . . )

I put it like this to Holly Black:

It does not surprise me in the slightest that Karen Joy Fowler and Ursula Le Guin are friends. But it surprises me HUGELY that I am making a living as a writer and therefore I have many writer friends. I constantly have to pinch myself. How on Earth did I get here? Please don’t let anyone take it away!

That fear is real: many writers don’t make a living at it for their whole lives. It takes a long time for most of us to get published (took me close to twenty years) and then once you are published there’s no guarantee that your books will keep selling. Styles of writing go out of fashion. So do genres.

Your comments were all so useful, I thought I’d respond in more detail:

Danica’s point is a really good one: “I guess we (meaning non-writers) don’t always think of publishing as an industry and don’t realize that most writers must be connected somehow.”

That’s so true. I remember the first science fiction convention I went to back in 1993. I was astonished to see all these writers and editors I’d heard of in the one place. All of them clearly knew each other and were, in fact, a community. A pretty big community that consisted not only of those whose living was directly tied to the publishing industry (writers, editors, publishers, publicists etc) but also readers and fans and a handful of students and scholars. Long before I sold a single short story I was becoming friends with the likes of Ellen Datlow, Samuel R. Delany, Ellen Kushner, Delia Sherman, and Terri Windling. It was astonishing.

That community—of science fiction people— is the oldest genre community I know of and has roots that go back to the late 1920s. There are also romance communities, crime fiction communities, YA communities etc., and to a lesser extent mainstream lit fic communities (though I suspect that the easy access of fans to pros is not so strong in the lit fic world).

Tole said: “Perhaps it’s not so much that we are surprised that you know each other, as much as amazed at how lucky you are to not only have the talent and perseverance to write a novel, but that you have an amazing set of friends as well.”

I am also amazed by that. I mean, yes, I said above that we’re not that different from everyone else, but my writer friends understand the ins and outs of this weird job we have better than anyone else. No matter what questions I have there’s someone I know who’s been through it before and can help me out. “My book’s been remaindered! Does that mean my career is over?” “Barnes & Noble aren’t stocking my book! Does that mean my career is over?” “How do you write action scenes?” “What’s the best writing software?” and so on and so forth. When I have a success that’s hard to explain to people outside the industry (my book is on the BBYA) my YA writer friends get it and can celebrate with me and vice versa.

Having peers is a wonderful, wonderful thing. And when your peers are as talented and amazing as mine. Well, it’s pinching yourself time.

JS Bangs made two excellent points:

1) People think of authors as solitary geniuses scribbling away and living on water and crusts of bread, without any contact with others of their kind.

2) It feeds people’s fear that the publishing industry is all about who you know.

1) There are writers like that. There are definitely working writers who live a long way from their peers and don’t ever meet them at conferences and convention and so on. But I think they’re getting rarer. The internet has allowed more and more people in the same industry to be in contact with each other and break down that isolation. Is very good thing!

2) Oh, yes, that old bugbear. Pretty much every industry from medicine to the building industry to agriculture has a certain amount of who-you-know going on. The world runs on personal relationships. What most people who are paranoid about the publishing industry don’t get is that an unpublished writer knowing some editors may get them read but guarantees nothing beyond that. I’ve had editor friends since 1993. A decade later I sold my first novel.

I know plenty of writers who started selling before they’d met a single person in the industry.1 Knowing people in the industry means that it’s easier to figure out how it works—you have friends you can ask—but it doesn’t mean anything if you have no talent.

Camille expanded on the solitary point: “I think, too, it’s because you can write from anywhere. With lawyers and professors and the like, generally you have to congregate in a place to get anything done. (Less now, with the Internet, but still, predominantly people go TO work.) You HAVE to physically associate with your colleagues. Writers can live anywhere and yeah, somebody above said we think of writing as being a solitary exercise.”

That’s true. Part of my knowing so many writers has to do with my living in two very big cities: Sydney and NYC. And in both cities the writers in my genre have made an effort to make contact. Because so many of us write alone, I think the need for community is much stronger than those who work with people in their profession every day.

Of course, there are still writers out there who don’t know other writers and aren’t part of any writing communities.

Herenya: “I think it’s because we know who these other writers are. If I started talking about who my friends are, people would look at me blankly because none of my friends have done anything to warrant that sort of recognition (yet!) But you talk about your friends, and I think ‘oh, yes, I know who they are, I was reading one of their books yesterday.’ It’s a bit like the same sense of surprise you get when you find you and a friend / acquaintance ‘know’ someone in common, but with the awe factor involved, because we only know them through their writing and not personally.”

That makes a lot of sense to me and jibes with my own experience. The awe factor is nicely summed up by Bill: “Myself, I’m still so amazed that certain books exist at all (say, Stranger in a Strange Land) I can’t rationally believe that it was typed by hand by a human being named Robert Heinlein. Books, especially books that change your life, are inherently mystical objects to those of us on the receiving end.”

Even though I write books myself, I still feel that way about the books that move me. There is something fundamentally mysterious about the process of creating (no matter what you create). I think that’s why so many writers struggle to explain where they get their ideas.

On that note, I should probably get back to doing some creating of my own.

- Scott Westerfeld and John Scalzi are two that come to mind.

Blog: Librarian Avengers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Grammer, Passive Aggressive Notes, Humor, Grammer, Passive Aggressive Notes, Add a tag

You can now mock the poor fools who slept through 8th grade punctuation day by contributing to the “Blog” of “Unnecessary” Quotation Marks.

Quotation marks for emphasis? Fie!

While you are out, visit the Passive Aggressive Notes blog and enjoy the work of some self-appointed Social Contract enforcers.

Just a suggestion.

Also? Can you “please” do the dishes?

Thanks.

-Librarian Avenger

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: science fiction, Delany, genre, theory, Add a tag

Susanna Mandel offered a thoughtful column at Strange Horizons this week, "On SF and the Mainstream, or, Rapidly Changing Scenery", writing from the perspective of someone who hasn't had the chance to keep up with a lot of what's been going on in the science fiction/fantasy community over the last five or so years. I sympathized a lot, having started this blog, in fact, as someone in just about exactly that position. (I'm really interested, too, to see what she's going to discuss in her future columns, which she says will be about pre-1800 writings.)

Richard Larson was inspired by the column to ask for some discussion that moves beyond content to probe the differences between SF and other sorts of things:

I would love for someone to be engaging the SF/mainstream literature discussion with the goal of making formal distinctions, of ignoring content completely and trying to figure out how the experience of reading mainstream literature differs from that of reading genre fiction, and what formal factors are contributing to that experience.Earlier, Paul Di Filippo posted the results of a panel at Readercon about a "slipstream canon", and Paul Kincaid responded, raising the point that there's hardly any such thing as a "pure genre" (no matter how you define "genre") and that the "canon" is a fine list of wonderful things to read, but these aren't texts that really have a whole lot in common.

Sarah Monette responded to both the list and to Kincaid's response by wondering if "genre" isn't the wrong word, and misleading. She proposes "modality" instead:

Contrarealism--or unrealism--(science fiction, fantasy, supernatural horror, magic realism . . . slipstream) is a modality. Because these things inflect a story on a level a priori to the narrative itself. If a genre is a kind of story, a modality is a kind of approach to a story. You can tell the same story in any modality. E.g., Cinderella. You can tell it as Coal Miner's Daughter (realism). You can tell it as a pararealistic Horatio Alger story. (Which I suppose some may argue is what Coal Miner's Daughter is. Not actually having seen the movie, I can't testify personally. The new Will Smith thing about the homeless man who becomes a stockbroker is also Cinderella. Realistic or para-?) Or you can tell it as a fantasy (Disney!). (I'm sure also that you can tell it as a science fiction story ... ooh, wait. Psion.) The narrative elements will not change. (Whereas, if you tell Cinderella as a horror story, the narrative elements do change. Hence we conclude that horror is a genre. QED.)It's worth also bringing into this some of the reviews of Interfictions

Meanwhile, the old New Weird discussions have been made public once again.

Okay, so there's a bunch of stuff. And it all brings me back to what Richard Larson asked -- how does the experience of reading something called X differ from the experience of something called Y (or not-X)? That's a question I find far more interesting than how to define X, Y, and not-X.

It all brings me back, as so much does, to Samuel Delany, who has done a little bit of what Larson seems to be looking for (mostly in Starboard Wine, which is very difficult to get hold of, but it will be generally available again either in the fall of 2008 or spring of 2009. More on that later).

Delany has called SF a "field phenomenon" that can only be described, not defined. He has argued that "There's no reason to run SF too much back before 1926" because

More, Kepler, Cyrano, and even Bellamy would be absolutely at sea with the codic conventions by which we make sense of the sentences in a contemporary SF text. Indeed, they would be at sea with most modern and post modern writing. It's just pedagogic snobbery (or insecurity), constructing these preposterous and historically insensitive genealogies, with Mary Shelley for our grandmother or Lucian of Samosata as our great great grandfather.(Adam Roberts has an interesting take on this in his history of science fiction, but I'm no longer near the library I borrowed the book from, and my memory of it is too unspecific to be able to paraphrase accurately.)

In one of his most important essays, "Dichtung und Science Fiction" (in Starboard Wine), Delany says, "For an originary assertion to mean something for a contemporary text, one must establish a chain of reading and preferably a chain of discussion as well." In another essay, "Science Fiction and Literature", he states, "To say that a phenomenon does have a significant history is to say that its history is different from the history of something else: that's what makes it significant."

I've said before that where a text is published can affect how it is read, including how it is categorized and understood by the reader. We see that in some of the reviews for Interfictions, where many of the stories are judged based on the purpose of the anthology, which of course is justifiable, but I also wonder how at least some of them would fare in an entirely different context. In fact, much of what is new about what's happening in the SF community right now -- the changes Susannah Mandel and others notice -- may be more the creation of new contexts than the creation of new types of fiction (about which I've got some of the same questions as Dan Green poses in his review and Paul Kincaid raises in his response to the "slipstream canon").

I'm wary of a form/content distinction, because it seems to me more an occasionally-useful illusion than an idea that really fosters good analysis, but how texts create reading experiences, and how those experiences change in different eras and circumstances does, indeed, interest me. That's an idea worth applying to those New Weird discussions -- what were the circumstances that made such discussions so energetic, combative, and sometimes insane? What was the effect of those discussions on writers' practices (if any), and why does it matter? Was the New Weird a momentary blip, more passion than substance, or was it a historically important argument/label/concern/whatever? What was it trying to be different from, and why?

If we want to map the topography of literary history, including all the little hills and dales, then texts alone will not explain vastly different reading experiences, because the contexts in which the texts are produced, distributed, received, and discussed contribute to that history. Such a conversation would, I think, allow more insight than yet another argument about how to define and delineate different types of fiction based on the texts alone, or on some mythical essential qualities those texts are supposed to possess.

Blog: The Excelsior File (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: summer, trash, summer reading, genre, Add a tag

"Read the Dell paperback."

"Read the Dell paperback."

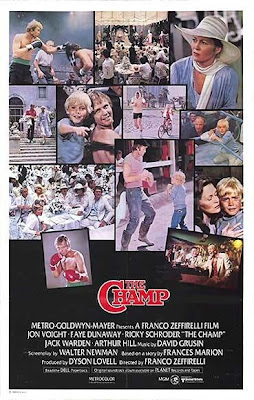

You have to be of a certain age to recall when those words would come at the end of a movie trailer. It was usually some genre film, something a little exploitative, a summer popcorn movie that was either based on the kind of paperback people would buy at the checkout stands in supermarkets or was written in haste between the editing of the film and the release date. I think half of these movies were produced by Roger Corman's American International Pictures because that was usually the first part of the announcer's sign-off: "An American International picture. Read the Dell paperback."

How many people bought those books? It's hard to say though there's a booming business of these titles on eBay. It's nice to know there was a time when major motion pictures and the venues that advertised them -- theatres and television -- once actually used to use summer as a time to promote reading, even if it was merely an attempt to wring every last penny of profit from their films.

Today I am singing the praises of that ghetto of fiction known as Trash, or sometimes Beach Reading, and almost always as Genre. I'm not necessarily digging into the actual trash mentioned above but that fiction which tends to get marginalized because of its connection to popular culture. I won't attempt an exhaustive list of titles or suggestions, instead I'm taking a look at some of the books that many of my friends and I read and passed around during the summers when we were teens. My goal is to suggest some older titles that are still around and just under the radar of most young adults. If some of these titles seem like classics of their genre, well, I can't pretend any of us knew or cared about what sort of shelf life these titles would assume when we first read them. One of my first "adult" summer reads was Ian Flemming's Bond classic Diamonds Are Forever. I bought it at some yard sale, among the go-cart parts and old kitcheware, laid out on a blanket with a bunch of other trash. I was eleven and it cost all of a quarter. I had seen a couple of Bond movies prior to reading this book and I might have already seen the film version, but on a lazy July afternoon I picked this thing up and started to read.

One of my first "adult" summer reads was Ian Flemming's Bond classic Diamonds Are Forever. I bought it at some yard sale, among the go-cart parts and old kitcheware, laid out on a blanket with a bunch of other trash. I was eleven and it cost all of a quarter. I had seen a couple of Bond movies prior to reading this book and I might have already seen the film version, but on a lazy July afternoon I picked this thing up and started to read.

It might sound obvious to say this, but at the time I remembered thinking the book was nothing like the movies. There was something way more adult about all this, the language was foreign to me, the pacing and storytelling alien. It was tough slog at first because I was still trying to marry the book and images from the movie into my still-developing cranium. And then there was all that narrative, all those points where the author explained Bonds thinking and rationale. Huh, there was actually some thinking going on behind all that action, some deep cover and intel gathering. He wasn't just a spy or a man of action but a trained agent in the British Secret Service. There were dimensions to his character and *pop* suddenly Bond is a bit more real. Oh, and here's a surprise: it was really about diamond smuggling, with no evil villain planning to send a laser into space to blow up parts of the world.

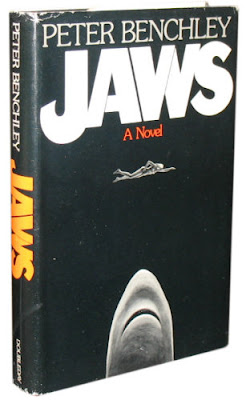

I had two other Bond books in my collection -- did I pick them up at the same time? -- but I don't recall reading them. And I've meant to go back and reread Diamonds Are Forever or any other Flemming that looked interesting to see what my adult mind makes of it all. A few years back they repackaged the covers of the books, upped them to trade paper size (mine were the smaller paperbacks), which I found appealing. I would need to reconfirm this, but readers deep into the Alex Rider series (or even the Young Bond series that's a few titles in) might enjoy a little old school cold war spy genre fiction. From here one could suggest some Robert Ludlum, John le Carre, or Len Deighton. I am a particular fan of Deighton's Harry Palmer books and equally of the movie adaptations which featured Michael Caine. It's Caine's spymaster turn that is the physical inspiration for Austin Powers which is better appreciated when you get the joke. You might even be able to introduce a spy fiction buff to the broccoli that is Graham Greene, especially Our Man in Havana which borders on parody of the genre. The penultimate summer movie, the one that actually created the mold for all summer blockbuster movies, is Jaws. When it came out I felt compelled to read the book first. In fact, knowing it was a bestseller before a movie I almost felt a certain sense of indignation that a movie had been made from the book and that most people would see the movie and never actually read the books.

The penultimate summer movie, the one that actually created the mold for all summer blockbuster movies, is Jaws. When it came out I felt compelled to read the book first. In fact, knowing it was a bestseller before a movie I almost felt a certain sense of indignation that a movie had been made from the book and that most people would see the movie and never actually read the books.

I was a teenage boy and self-righteous indignation, especially over things I knew little or nothing about, came naturally.

I don't remember how I came into possession of my paperback of Jaws but I do know that I lent it out twice before trying to read it myself. I just had a hard time getting started. I must have reread the first 20 pages a half dozen times before I sat down determined to bust my way through it. I gave myself a 50 page deadline and had finished twice as many pages before I thought to look at the page numbers. The rest of the book came easy and when I finally saw the movie... well, let's leave my views about Steven Spielberg for another time and forum.

Jaws, at its simplest, falls into the man-against-nature horror genre. Typically there is a thing that is out to get people and there's a lot of running around trying to sort out what the thing wants and how to kill or outwit it. Character plays second fiddle to the action, which requires the story to be populated either with people of average or lesser intelligence than the reader to luck into a resolution or, at best, a challenge of wills in which the strongest (protagonist/s) survives.

For somewhat similar books I don't imagine there's any harm in Michael Chrichton's Jurassic Park, though I think The Andromeda Strain is a lesser known story that teen readers might enjoy. Also Robin Cook's Coma, William Wharton's Birdy, William Goldman's Magic (skip the film, the adaptation is atrocious), and Benchley's post-Jaws follow-ups The Deep and The Island.

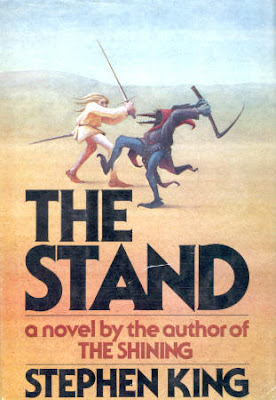

For many I knew growing up summer reading could be summed up in two word: Stephen King. Personally I had some problems with early Stephen King where the characters had a paranormal abilities that were referred to as "the push" (in Firestarter) or "the shining" and I couldn't fully grok King the way my friends had. Until The Stand.

Until The Stand.

Much talk these days about apoca-lit in YA fiction, much talk about how kids really seem to dig the political, ethical and moral questions that arise when the world faces a destructive-yet-unifying cataclysm like a comet knocking the moon off course or a plague devouring humanity. But when you weld these elements together with the muscular fists of a writer like Stephen King you have the ultimate in summer reads. Biological weapon released, killing a vast majority of the population who are haunted by visions of either an old woman near a corn field or a handsome stranger in the desert, drawn to either one in a battle of good verses evil for the survival of mankind. I haven't even glanced at this book since it's original publication and I can still remember images clearly from the book, more so than things I have read in the past year. Rib-sticking, something that isn't going to leave you feeling empty, yet nothing that's going to show up on an SAT test.

I would say that any Stephen King would work but I haven't read them all and I have encountered some duds, especially in the 1990's. Stick with the classic King, the books that made his name, like Carrie, 'Salem's Lot, Firestarter or The Shining. If you've got a reader who's already run those books down why not give them a taste of Ira Levin's Rosemary's Baby, William Peter Blatty's The Exorcist, David Seltzer's The Omen, or Jay Anson's The Amityville Horror. These aren't exactly apoca-lit titles (I've got one coming up next) but they are still very sturdy reads.

I read another book the same summer I read The Stand and that was Lucifer's Hammer by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. Now here was something fun: a newly discovered comet originally believed to pass Earth appears to be on a collision course. While the scientific community assures the public that impact isn't likely a televangelist fans the flames of fear and suddenly everyone's on a survivalist kick. The comet breaks up as it nears Earth and lands in various places across the planet, causing earthquakes, volcano eruptions and tsunamis-a-plenty. What's left of civilization is in ruins, fighting for survival among militant cannibals. Fun! Larry Niven's name is probably familiar to science fiction fans for many books including the Ringworld series. I have tried to start other Niven/Pournelle collaborations but they just didn't click for me. That aside, what were talking about now is science-fiction which has steadily increased in its general approval since when I was a lad and is now (finally) practically respectable literature. Why, 30 years ago Phillip K. Dick might have had the word "wacko" in front of his name but now after Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report and A Scanner Darkly -- films all made from Dick stories -- he is being embraced as a unique and genuine American voice. Blade Runner and Total Recall were not the names of Dick books (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and the short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale respectively) and it might be fun (in a devious way) to present the originals sans mention of their movie adaptations on the cover to a reader to see if they make the connection.

Larry Niven's name is probably familiar to science fiction fans for many books including the Ringworld series. I have tried to start other Niven/Pournelle collaborations but they just didn't click for me. That aside, what were talking about now is science-fiction which has steadily increased in its general approval since when I was a lad and is now (finally) practically respectable literature. Why, 30 years ago Phillip K. Dick might have had the word "wacko" in front of his name but now after Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report and A Scanner Darkly -- films all made from Dick stories -- he is being embraced as a unique and genuine American voice. Blade Runner and Total Recall were not the names of Dick books (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and the short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale respectively) and it might be fun (in a devious way) to present the originals sans mention of their movie adaptations on the cover to a reader to see if they make the connection.

A younger reader with a hunger for actual science fiction or fantasy may have already discovered the Douglas Adams Hitchhiker series, or the Anne McCaffrey Dragonriders of Pern books (one was good enough for me, thanks), or Octavia Butler's dystopian Parable titles -- all fine suggestions if they haven't been previously experienced. But there was one book that really tweaked me one summer and that was Theodore Sturgeon's More Than Human. There was something truly alien about the feel of this story about a group of people with various powers who could blend together as one, sort of a next step in human evolution. To my younger self it felt like The Fantastic Four crossed with The Twilight Zone and only later did I understand some of the more psychological aspects. Sturgeon also wrote the novelization for the movie Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, giving him some true trash credentials. For something a bit more light and fun, a bit more Renaissance Faire-meets-Star Wars, try Robert Silverberg's Lord Valentine's Castle, the first-written-but-middle-title in the timeline of his Majipoor series. I think it makes a good transition from a fantasy world reader into the more politicised sci-fi world. I'm sure that statement's going to upset someone. So be it. It's what I read then and what I'm suggesting now. I'm going to cheat a bit here and talk about my summer reading after my first year of college. Technically I was still a teen, and I think that if I'd had this genre tossed my way earlier I'd have loved it. I'm talking about detective stories, especially those old school hard-boiled types. I'm talking about that triumvirate of explorers from the dark underbelly of the American psyche: Dashiel Hammet, James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler. Hammet, the former Brinks man invented both Sam Spade and Nick and Nora Charles and practically the entire genre we now recognize as hard-boiled. Cain's gritty stories traffic in a world of femme fatales and dirty double crosses, a bit on the misogynist side of things but no one comes out smelling like a rose with Cain.

I'm going to cheat a bit here and talk about my summer reading after my first year of college. Technically I was still a teen, and I think that if I'd had this genre tossed my way earlier I'd have loved it. I'm talking about detective stories, especially those old school hard-boiled types. I'm talking about that triumvirate of explorers from the dark underbelly of the American psyche: Dashiel Hammet, James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler. Hammet, the former Brinks man invented both Sam Spade and Nick and Nora Charles and practically the entire genre we now recognize as hard-boiled. Cain's gritty stories traffic in a world of femme fatales and dirty double crosses, a bit on the misogynist side of things but no one comes out smelling like a rose with Cain.

For my money though it's Chandler all the way. Phillip Marlowe is his man, prowling the streets of Los Angeles in the 30's and 40's, pulling the most disparate threads and ties them into tangled nets that eventually solve the crime. Chandler claims to have been influenced by Hammet but it's Chandler who perfected the lyricism of the private detective's inner voice. You might have better luck teaching kids how to write more concisely, and more vividly, by teaching them from Chandler's stories than from Hemingway. Chandler, in describing Marlowe lighting a pipe in the smoking car of a train, taught me a word that I hope one day to use in my own fiction: frowst.

I loved this summary of Phillip Marlowe from Wikipedia:

Philip Marlowe, is not a stereotypical tough guy, but rather a complex and sometimes sentimental figure who has few friends, attended college for a while, speaks a little Spanish, at times admires Mexicans, and is a student of chess and classical music. He will also refuse money from a prospective client if he is not satisfied that the job meets his ethical standards.

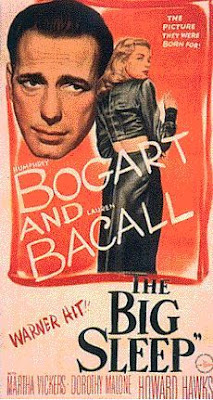

And to think they used to call this kind of stuff pulp, after the cheap paper it used to be printed on in magazines. They made plenty of good movies from this stuff as well, inspiring an entire genre of film called noir: The Postman Always Rings Twice, Mildred Pierce, The Maltese Falcon, The Thin Man, The Big Sleep, Farewell, My Lovely. All good stuff.

* * * * *

What these books and many, many more like them have in common is that they were paperbacks, they were cheap and, without exception, they were intended for adult audiences. If there's one thing teens love to do is assume they are ready for "adult" reading material as soon as the bug hits them, and I don't imagine it's been any different throughout history.

But looking back and then turning forward I am struck with how unified and national tastes were once upon a time. Many of these books weren't on the bestseller's lists because they had high orders from bookselling superstores, these were the books everyone read, and knew, and talked about. Maybe the closest thing we have to something similar in recent years is Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code, and the popularity of that book remains a mystery to me even today as I found it filled me with inertia. But there was a time (I imagine some publishers and editors moon about this late at night at their favorite speakeasy) when the bestseller list was full of books -- for better or worse -- that were actually read by lots and lots of people and everyone would talk about them the way people now stand around and talk about the results of American Idol or the most recent developments on Lost. There are fine books out there, yes, yes, but how many of them are really capturing the national imagination and get read (before being optioned for movie rights) or that aren't being flogged by Oprah?

As I said from the beginning, this was my list and my experience. These were the books I discovered as a teen reader, or wish I'd discovered earlier, that make for good, solid summer reads. I'd love to hear what others discovered in a similar vein, particularly those who can speak to the romance genre that, as a boy, never held any pull with me.

Where to now? Let's see...

First there was Low Humor

Then there was Non-fiction

Next up: Shorts, perfect for summer weather

Kit,

I'm sure your great illustrations helped our young reader recognize the adverbs.

You know what they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Thanks for the post.