new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: African American Studies, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 54

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: African American Studies in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Ayana Young,

on 3/1/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Africana Studies,

*Featured,

Online products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Robert Repino,

W.E.B. Du Bois,

OAASC,

Lynching of Sam Hose,

Non Fiction Literature,

Post-Apocalyptic Literature,

Science Fiction by W.E.B. Du Bois,

The Comet by W.E.B. Du Bois,

Literature,

black history month,

America,

black history,

African American Studies,

African American History,

Add a tag

There is a moment in the George Miller film Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome (1985) that has stuck with me over the two decades since I first saw it. A bedraggled Max (Mel Gibson) is escorted through the crumbling desert outpost of Bartertown.

The post W.E.B. Du Bois and the literature of upheaval appeared first on OUPblog.

Street Poison is an illuminating portrait of the flawed and fascinating life of Iceberg Slim. Though not well known in literary circles, his books have had a profound effect on music, film, and inner-city culture. Gifford, his biographer, crafts a highly readable account of mid-20th-century African American history that feels both timely and relevant. Books [...]

By: Rhianna Walton,

on 12/11/2014

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Alastair Bonnett,

Jeff Hobbs,

Eula Biss,

Roxane Gay,

Brian Turner,

Anita Reynolds,

Biography,

Sociology,

Politics,

Best Books of the Year,

Geography,

Crime,

World History,

Russia,

African American Studies,

Gender Studies,

Rebecca Solnit,

Masha Gessen,

American Studies,

Health and Medicine,

Feminist Studies,

Walter Kirn,

Leslie Jamison,

Add a tag

A lot is made of the romance of bookstores. The smell of paper! The joy of discovery! The ancient, cracking leather bindings of books with dated inscriptions! And it's true that bookstores are magical places to browse and linger — just maybe not in the two days before Christmas. Because in the swirling mad hum [...]

By: Rhianna Walton,

on 9/10/2014

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

International Studies,

Beyond the Headlines,

Jeff Hobbs,

Alice Goffman,

Gary Haugen A,

Laurence Ralph,

Nell Bernstein,

Law,

Sociology,

Crime,

African American Studies,

Add a tag

Like many Americans I walk an uneasy line between being appalled by the living conditions of the inner-city and being afraid of them. The educational and socio-economic disadvantages common in inner-city neighborhoods, along with the high rates of drug- and gang-related violent crime, are already hard problems to grasp and tackle. The fact that these [...]

By: Geoff Dyer,

on 5/21/2014

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Brenda Wineapple,

Henry Mayer,

J Anthony Lukas,

Taylor Branch,

Q&A,

World History,

African American Studies,

Nautical,

Isabel Wilkerson,

Geoff Dyer,

Add a tag

Describe your latest book/project/work. Another Great Day at Sea is an account of my experiences aboard the USS George H. W. Bush. It's a masterpiece of the form, widely hailed as the best book ever written about my time on the George H. W. Bush. Also, I have two early novels, The Colour of Memory [...]

We asked our readers: What was the last book that you couldn't put down, that kept you up all night, that you couldn't stop recommending? We were delightfully surprised by the number of replies we received. Here are some of our favorites. We'll be posting more on a regular basis, so check back often. And [...]

By: ErinM,

on 3/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

baker,

performance,

AASC,

NAACP,

martin luther king jr,

josephine,

*Featured,

march on washington,

TV & Film,

racial equality,

Theatre & Dance,

Online products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Oxford AASC,

josephine baker,

anne cheng,

oxford african studies,

baker’s,

Music,

History,

Biography,

civil rights,

America,

African American Studies,

Add a tag

By Tim Allen

Josephine Baker, the mid-20th century performance artist, provocatrix, and muse, led a fascinating transatlantic life. I recently had the opportunity to pose a few questions to Anne A. Cheng, Professor of English and African American Literature at Princeton University and author of the book Second Skin: Josephine Baker & the Modern Surface, about her research into Baker’s life, work, influence, and legacy.

Josephine Baker, as photographed by Carl Von Vechten in 1949. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Baker made her career in Europe and notably inspired a number of European artists and architects, including Picasso and Le Corbusier. What was it about Baker that spoke to Europeans? What did she represent for them?

It has been traditionally understood that Baker represents a “primitive” figure for male European artists and architects who found in Baker an example of black animality and regressiveness; that is, she was their primitive muse. Yet this view cannot account for why many famous female artists were also fascinated by her, nor does it explain why Baker in particular would come to be the figure of so much profound artistic investment. I would argue that it is in fact Baker’s “modernity” (itself understood as an expression of hybrid and borrowed art forms) rather than her “primitiveness” that made her such a magnetic figure. In short, the modernists did not go to her to watch a projection of an alienating blackness; rather, they were held in thrall by a reflection of their own art’s racially complex roots. This is another way of saying that, when someone like Picasso looked at a tribal African mask or a figure like Baker who mimics Western ideas of Africa, what he saw was not just radical otherness but a much more ambivalent mirror of the West’s own complicity in constructing and imagining that “otherness.”

Baker was present at the March on Washington in August 1963 and stood with Martin Luther King Jr. as he gave his “I have a dream” speech. What did Baker contribute to the struggle for civil rights? How was her success in foreign countries understood within the African American community?

These are well-known facts about Baker’s biography: in the latter part of her life, Baker became a very public figure for the causes of social justice and equality. During World War II, she served as an intelligence liaison and an ambulance driver for the French Resistance and was awarded the Medal of the Resistance and the Legion of Honor. Soon after the war, Baker toured the United States again and won respect and praise from African Americans for her support of the civil rights movement. In 1951, she refused to play to segregated audiences and, as a result, the NAACP named her its Most Outstanding Woman of the Year. She gave a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall for the NAACP, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Congress of Racial Equality in 1963.

What is fascinating as well, however, is the complication that Baker represents to and for the African American community. Prior to the war and her more public engagement with the civil rights movement, she was not always a welcome figure either in the African American community or for the larger mainstream American public. Her sensational fame abroad was not duplicated in the states, and her association with primitivism made her at times an embarrassment for the African American community. A couple of times before the war, Baker returned to perform in the United States and was not well received, much to her grief. I would suggest that Baker should be celebrated not only for her more recognizable civil rights activism, but also for her art: performances which far exceed the simplistic labels that have been placed on them and which few have actually examined as art. These performances, when looked at more closely, embody and generate powerful and intricate political meditations about what it means to be a black female body on stage.

Did your research into Baker’s life uncover any surprising or unexpected bits of information? What was the greatest challenge you experienced in carrying out your research?

I was repeatedly stunned by how much writing has been generated about her life (from facts to gossip) but how little attention has been paid to really analyzing her work, be it on stage or in film. The work itself is so idiosyncratic and layered and complex that this critical oversight is really a testament to how much we have been blinded by our received image of her. I was also surprised to learn how insecure she was about her singing voice when it is in fact a very unique voice with great adaptability. Baker’s voice can be deep and sonorous or high and pitchy, depending on the context of each performance. In the film Zou Zou, for example, Baker is shown dressed in feathers, singing while swinging inside a giant gilded bird cage. Many reviewers criticized her performance as jittery and staccato. But I suggest that her voice was actually mimicking the sounds that would be made, not by a real bird, but by a mechanical bird and, in doing so, reminding us that we are not seeing naturalized primitive animality at all, but its mechanical reconstruction.

For me, the challenge of writing the story of Baker rests in learning how to delineate a material history of race that forgoes the facticity of race. The very visible figure of Baker has taught me a counterintuitive lesson: that the history of race, while being very material and with very material impacts, is nonetheless crucially a history of the unseen and the ineffable. The other great challenge is the question of style. I wanted to write a book about Baker that imitates or at least acknowledges the fluidity that is Baker. This is why, in these essays, Baker appears, disappears, and reappears to allow into view the enigmas of the visual experience that I think Baker offers.

Baker’s naked skin famously scandalized audiences in Paris, and your book is, in many respects, an extended analysis of the significance of Baker’s skin. Why study Josephine Baker and her skin today? What does she represent for the study of art, race, and American history? Did your interest in studying Baker develop gradually, or were you immediately intrigued by her?

I started out writing a book about the politics of race and beauty. Then, as part of this larger research, I forced myself to watch Josephine Baker’s films. I say “forced” because I was dreading seeing exactly the kind of racist images and performances that I have heard so much about. But what I saw stunned, puzzled, and haunted me. Could this strange, moving, and coated figure of skin, clothes, feathers, dirt, gold, oil, and synthetic sheen be the simple “black animal” that everyone says she is? I started writing about her, essay after essay, until a dear friend pointed out that I was in fact writing a book about Baker.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on Twitter @timDallen.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Discussing Josephine Baker with Anne Cheng appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/24/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

black history month,

woodson,

African American Studies,

african,

strived,

United States,

Abraham Lincoln,

leffler,

fredrick douglass,

American National Biography,

fredrick,

African Americans,

*Featured,

luncheon,

Online Products,

ANB,

African American lives,

Dr Carter Woodson,

abernathy,

attachment_35720,

History,

US,

Add a tag

February marks a month of remembrance for Black History in the United States. It is a time to reflect on the events that have enabled freedom and equality for African Americans, and a time to celebrate the achievements and contributions they have made to the nation.

Dr Carter Woodson, an advocate for black history studies, initially created “Negro History Week” between the birthdays of two great men who strived to influence the lives of African Americans: Fredrick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. This celebration was then expanded to the month of February and became Black History Month. Find out more about important African American lives with our quiz.

Rev. Ralph David Abernathy speaks at Nat’l. Press Club luncheon. Photo by Warren K. Leffler. 1968. Library of Congress.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men & women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. The American National Biography is the first biographical resource of this scope to be published in more than sixty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post African American lives appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KimberlyH,

on 2/19/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

History,

US,

avant-garde,

Jazz,

African American Studies,

swing,

Louis Armstrong,

John Coltrane,

coltrane,

AASC,

duke ellington,

bebop,

Miles Davis,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

kenny,

Online Products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Oxford AASC,

African American National Biography,

Art Farmer,

Benny Carter,

Charlie Parker,

Don Byron,

Ernestine Anderson,

Ernie Andrews,

free jazz,

hard bop,

Harry “Sweets” Edison,

Jon Hendricks,

Kenny Barron,

Kenny Dorham,

Roy Hargrove,

Scott Yanow,

barron,

yanow,

Add a tag

By Scott Yanow

When I was approached by the good folks at Oxford University Press to write some entries on jazz artists, I noticed that while the biggest names (Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, etc.) were already covered, many other artists were also deserving of entries. There were several qualities that I looked for in musicians before suggesting that they be written about. Each musician had to have a distinctive sound (always a prerequisite before any artist is considered a significant jazz musician), a strong body of work, and recordings that sound enjoyable today. It did not matter if the musician’s prime was in the 1920s or today. If their recordings still sounded good, they were eligible to be given prestigious entries in the African American National Biography.

Some of the entries included in the February update to the Oxford African American Studies Center are veteran singers Ernestine Anderson, Ernie Andrews, and Jon Hendricks; trumpet legends Harry “Sweets” Edison, Kenny Dorham, and Art Farmer; and a few giants of today, including pianist Kenny Barron, trumpeter Roy Hargrove, and clarinetist Don Byron.

In each case, in addition to including the musicians’ basic biographical information, key associations, and recordings, I have included a few sentences that place each artist in their historic perspective, talking about how they fit into their era, describing their style, and discussing their accomplishments. Some musicians had only a brief but important prime period, but there is a surprising number of artists whose careers lasted over 50 years. In the case of Benny Carter, the alto saxophonist/arranger was in his musical prime for a remarkable 70 years, still sounding great when he retired after his 90th birthday.

Jazz, whether from 90 years ago or today, has always overflowed with exciting talents. While jazz history books often simplify events, making it seem as if there were only a handful of giants, the number of jazz greats is actually in the hundreds. There was more to the 1920s than Louis Armstrong, more to the swing era than Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller, and more to the classic bebop era than Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. For example, while Duke Ellington is justly celebrated, during the 49 years that he led his orchestra, he often had as many as ten major soloists in his band at one time, all of whom had colorful and interesting lives.

Because jazz has had such a rich history, it is easy for reference books and encyclopedias to overlook the very viable scene of today. The music did not stop with the death of John Coltrane in 1967 or the end of the fusion years in the late 1970s. Because the evolution of jazz was so rapid between 1920 and 1980, continuing in almost a straight line as the music became freer and more advanced, it is easy (but inaccurate) to say that the music has not continued evolving. What has happened during the past 35 years is that instead of developing in one basic way, the music evolved in a number of directions. The music world became smaller and many artists utilized aspects of World and folk music to create new types of “fusions.” Some musicians explored earlier styles in creative ways, ranging from 1920s jazz to hard bop. The avant-garde or free jazz scene introduced many new musicians, often on small label releases. And some of the most adventurous players combined elements of past styles — such as utilizing plunger mutes on horns or engaging in collective improvisations — to create something altogether new.

While many veteran listeners might call one period or another jazz’s “golden age,” the truth is that the music has been in its prime since around 1920 (when records became more widely available) and is still in its golden age today. While jazz deserves a much larger audience, there is no shortage of creative young musicians of all styles and approaches on the scene today. The future of jazz is quite bright and the African American National Biography’s many entries on jazz greats reflect that optimism.

Scott Yanow is the author of eleven books on jazz, including The Great Jazz Guitarists, The Jazz Singers, Trumpet Kings, Jazz On Record 1917-76, and Jazz On Film.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Kenny Barron 2001, Munich/Germany. Photo by Sven.petersen, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Jazz lives in the African American National Biography appeared first on OUPblog.

My novel The House Girl tells the story of two women: Lina Sparrow, a lawyer in modern-day New York, and Josephine Bell, a slave in 1850s Virginia. People often ask me why I chose to write about Josephine and who inspired her character. (They assume, I suspect, that Lina is a stand-in for myself: I [...]

By: ChloeF,

on 2/8/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

African American Studies,

African,

VSI,

Values,

society,

marijuana,

jamaica,

very short Introductions,

heritage,

divine,

*Featured,

Rastafari,

western values,

VSIs,

downpression,

ecological backlash,

Ennis B. Edmonds,

Rasta,

Rastafarian,

rastas,

Add a tag

By Ennis B. Edmonds

Recently, I was discussing my academic interest with an acquaintance from my elementary school days. On revealing that I have researched and written about the Rastafarian movement, I was greeted with a look of incredulity. He followed this look with a question: “How has Rastafari assisted anyone to progress in life?” My friend assured me he was aware that prominent and accomplished Rastas exist in Jamaica, however he was convinced that Rastafari did not contribute to the social and economic mobility of most of its adherents. Sensing that my friend was espousing a notion of progress based on rising social status and increasing economic resources — reflecting his own journey from a peasant farming family to an elementary school teacher to a highly regarded principal of a number of schools to an educational officer at present — I pointed out that Rastafari rejects this conventional notion of progress, especially when it is for a few at the exclusion of the many. Pointing out that I had no understanding of Rastafari until I started researching it, I left hoping that next time he engages in a conversation on Rastafari, he will do so with greater understanding and appreciation.

Unfortunately, my acquaintance’s attitude towards Rastafari is widely shared by those who judge progress and personal worth by social mobility and increasing material resources within a Western cultural f ramework. Conversely, Rastafari has articulated a trenchant critique of Western values and institutions, asserting that they are based on exploitation and oppression of both humans and the environment. Western values and institutions have sown seeds of discord, distrust, and conflict that translate into social disharmony and all the social ills that plague contemporary societies. The rapacious exploitation of natural resources in pursuit of profit have violated sound ecological principles and will ultimately trigger an ecological backlash (are we already experiencing this in changing weather patterns?). In this respect, Rastafari is an implicit call for us to examine the foundation on which our political, economic, and cultural institutions and values are constructed. Are they designed to cater to the interest of the whole human family or the interest of those who monopolize and manipulate power? Are they informed by a desire to live in harmony with other humans and nature or by a desire to dominate both?

ramework. Conversely, Rastafari has articulated a trenchant critique of Western values and institutions, asserting that they are based on exploitation and oppression of both humans and the environment. Western values and institutions have sown seeds of discord, distrust, and conflict that translate into social disharmony and all the social ills that plague contemporary societies. The rapacious exploitation of natural resources in pursuit of profit have violated sound ecological principles and will ultimately trigger an ecological backlash (are we already experiencing this in changing weather patterns?). In this respect, Rastafari is an implicit call for us to examine the foundation on which our political, economic, and cultural institutions and values are constructed. Are they designed to cater to the interest of the whole human family or the interest of those who monopolize and manipulate power? Are they informed by a desire to live in harmony with other humans and nature or by a desire to dominate both?

But Rastafari is much more than a critique of Western society; it is a fashioning of an identity grounded in a sense of the human relationship to the Divine and to the African heritage of most of its adherents. Thus for Rastas, the Divine is not just some transcendent, ethereal being, but an essential essence in all humans and a cosmic presence that pervades the universe. To be Rasta is to be awakened to one’s innate divine essence and to strive to live one’s life in harmony with the divine principles that govern the world, instead of living like “baldheads” (non-Rastas) who are sometimes driven to excess in their pursuit of ego-satisfaction. On a more cultural level, Rastafari seeks to cultivate for its adherents an identity and a lifestyle based on a re-appropriation on an African past. Rejecting the slave and post-slavery identity foisted upon them by colonial powers, early Rastas and their successors turned to their African heritage to reconstitute their cultural selves. Despite the derogation of Africa and the denigration of Africans in colonial discourse, Rastas proudly affirm themselves as Africans and posit that an African sense of spirituality that embraces communality and living in harmony with the forces of nature is not only in line with divine principles, but also makes for a more harmonious relationship among humans and a more sustainable future for the earth.

Many of us approach Rastafari from a sense of curiosity inspired by the dramatic imagery that dreadlocks present, rumours we have heard about the copious use of ganja (marijuana) by its adherents, or the realization that the enchanting rhythms and conscious lyrics of reggae are Rasta-inspired. However, a closer look will make us realize that Rastafari presents us with a perspective that can help us ask questions about the mainstream values and institutions of Western society and beyond. Do these values and institutions promote freedom, justice, harmony, opportunity, and sustainability? Long before the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement, Rastafari has been criticizing the “downpression,” inequities, and unsustainability of the political and economic structures of the world. How about how we regard our human selves? Are we just cogs in the wheel of an economic machine? Or do we have intrinsic value that is enhanced by living in harmony with other humans and our natural environment? You need not embrace Rastafari to appreciate Marley’s lyrics from “Survival”:

Click here to view the embedded video.

“In this age of technological inhumanity/Scientific atrocity/Atomic misphilosophy/Nuclear misenergy/It’s a world that forces lifelong insecurity.” Part of the liner notes from the album of the same name points the way out of this state of affairs: “But to live as one, equal in the eyes of the Almighty.”

Ennis B. Edmonds is Assistant Professor of African-American Religions and American Religions at Kenyon College, Ohio. His areas of expertise are African Diaspora Religions, Religion in America, and Sociology of Religion. His research has focused primarily on Rastafari, leading to Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers and Rastafari: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Judah Lion, By Weweje [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Appreciating the perspective of Rastafari appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/30/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

civil war,

illness,

African American Studies,

suffering,

refugee,

African American History,

emancipation proclamation,

reconstruction,

*Featured,

contraband,

Online Products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Oxford AASC,

Tim Allen,

freedmen,

Freedmen's Bureau,

health crisis,

Jim Downs,

Sick from Freedom,

freedpeople,

History,

US,

Add a tag

The editors of the Oxford African American Studies Center spoke to Professor Jim Downs, author of Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, about the legacy of the Emancipation Proclamation 150 years after it was first issued. We discuss the health crisis that affected so many freedpeople after emancipation, current views of the Emancipation Proclamation, and insights into the public health crises of today.

Emancipation was problematic, indeed disastrous, for so many freedpeople, particularly in terms of their health. What was the connection between newfound freedom and health?

I would not say that emancipation was problematic; it was a critical and necessary step in ending slavery. I would first argue that emancipation was not an ending point but part of a protracted process that began with the collapse of slavery. By examining freedpeople’s health conditions, we can see how that process unfolded—we can see how enslaved people liberated themselves from the shackles of Southern plantations but then were confronted with a number of questions: How would they survive? Where would they get their next meal? Where were they to live? How would they survive in a country torn apart by war and disease?

Due to the fact that freedpeople lacked many of these basic necessities, hundreds of thousands of former slaves became sick and died.

The traditional narrative of emancipation begins with liberation from slavery in 1862-63 and follows freedpeople returning to Southern plantations after the war for employment in 1865 and then culminates with grassroots political mobilization that led to the Reconstruction Amendments in the late 1860s. This story places formal politics as the central organizing principle in the destruction of slavery and the movement toward citizenship without considering the realities of freedpeople’s lives during this seven- to eight- year period. By investigating freedpeople’s health conditions, we first notice that many formerly enslaved people died during this period and did not live to see the amendments that granted citizenship and suffrage. They survived slavery but perished during emancipation—a fact that few historians have considered. Additionally, for those that did survive both slavery and emancipation, it was not such a triumphant story; without food, clothing, shelter, and medicine, emancipation unleashed a number of insurmountable challenges for the newly freed.

Was the health crisis that befell freedpeople after emancipation any person, government, or organization’s fault? Was the lack of a sufficient social support system a product of ignorance or, rather, a lack of concern?

The health crises that befell freedpeople after emancipation resulted largely from the mere fact that no one considered how freedpeople would survive the war and emancipation; no one was prepared for the human realities of emancipation. Congress and the President focused on the political question that emancipation raised: what was the status of formerly enslaved people in the Republic?

When the federal government did consider freedpeople’s condition in the final years of the war, they thought the solution was to simply return freedpeople to Southern plantations as laborers. Yet, no one in Washington thought through the process of agricultural production: Where was the fertile land? (Much of it was destroyed during the war; and countless acres were depleted before the war, which was why Southern planters wanted to move west.) How long would crops grow? How would freedpeople survive in the meantime?

Meanwhile, a drought erupted in the immediate aftermath of the war that thwarted even the most earnest attempts to develop a free labor economy in the South. Therefore, as a historian, I am less invested in arguing that someone is at fault, and more committed to understanding the various economic and political forces that led to the outbreak of sickness and suffering. Creating a new economic system in the South required time and planning; it could not be accomplished simply by sending freedpeople back to Southern plantations and farms. And in the interim of this process, which seemed like a good plan by federal leaders in Washington, a different reality unfolded on the ground in the postwar South. Land and labor did not offer an immediate panacea to the war’s destruction, the process of emancipation, and the ultimate rebuilding of the South. Consequently, freedpeople suffered during this period.

When the federal government did establish the Medical Division of the Freedmen’s Bureau – an agency that established over 40 hospitals in the South, employed over 120 physicians, and treated an estimated one million freedpeople — the institution often lacked the finances, personnel, and resources to stop the spread of disease. In sum, the government did not create this division with a humanitarian — or to use 19th century parlance, “benevolence” — mission, but rather designed this institution with the hope of creating a healthy labor force.

So, if an epidemic broke out, the Bureau would do its best to stop its spread. Yet, as soon as the number of patients declined, the Bureau shut down the hospital. The Bureau relied on a system of statistical reporting that dictated the lifespan of a hospital. When a physician reported a declining number of patients treated, admitted, or died in the hospital, Washington officials would order the hospital to be closed. However, the statistical report failed to capture the actual behavior of a virus, like smallpox. Just because the numbers declined in a given period did not mean that the virus stopped spreading among susceptible freedpeople. Often, it continued to infect formerly enslaved people, but because the initial symptoms of smallpox got confused with other illnesses it was overlooked. Or, as was often the case, the Bureau doctor in an isolated region noticed a decline among a handful of patients, but not too far away in a neighboring plantation or town, where the Bureau doctor did not visit, smallpox spread and remained unreported. Yet, according to the documentation at a particular moment the virus seemed to dissipate, which was not the case. So, even when the government, in the shape of Bureau doctors, tried to do its best to halt the spread of the disease, there were not enough doctors stationed throughout the South to monitor the virus, and their methods of reporting on smallpox were problematic.

You draw an interesting distinction between the terms refugee and freedmen as they were applied to emancipated slaves at different times. What did the term refugee entail and how was it a problematic description?

I actually think that freedmen or freedpeople could be a somewhat misleading term, because it defines formerly enslaved people purely in terms of their political status—the term freed places a polish on their condition and glosses over their experience during the war in which the military and federal government defined them as both contraband and refugees. Often forced to live in “contraband camps,” which were makeshift camps that surrounded the perimeter of Union camps, former slaves’ experience resembled a condition more associated with that of refugees. More to the point, the term freed does not seem to jibe with what I uncovered in the records—the Union Army treats formerly enslaved people with contempt, they assign them to laborious work, they feed them scraps, they relegate them to muddy camps where they are lucky if they can use a discarded army tent to protect themselves against the cold and rain. The term freedpeople does not seem applicable to those conditions.

That said, I struggle with my usage of these terms, because on one level they are politically no longer enslaved, but they are not “freed” in the ways in which the prevailing history defines them as politically mobile and autonomous. And then on a simply rhetorical level, freedpeople is a less awkward and clumsy expression than constantly writing formerly enslaved people.

Finally, during the war abolitionists and federal officials argued over these terms and classifications and in the records. During the war years, the Union army referred to the formerly enslaved as refugees, contraband, and even fugitives. When the war ended, the federal government classified formerly enslaved people as freedmen, and used the term refugee to refer to white Southerners displaced by the war. This is fascinating because it implies that white people can be dislocated and strung out but that formerly enslaved people can’t be—and if they are it does not matter, because they are “free.”

Based on your understanding of the historical record, what were Lincoln’s (and the federal government’s) goals in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation? Do you see any differences between these goals and the way in which the Emancipation Proclamation is popularly understood?

The Emancipation Proclamation was a military tactic to deplete the Southern labor force. This was Lincoln’s main goal—it invariably, according to many historians, shifted the focus of the war from a war for the Union to a war of emancipation. I never really understood what that meant, or why there was such a fuss over this distinction, largely because enslaved people had already begun to free themselves before the Emancipation Proclamation and many continued to do so after it without always knowing about the formal proclamation.

The implicit claim historians make when explaining how the motivation for the war shifted seems to imply that the Union soldiers thusly cared about emancipation so that the idea that it was a military tactic fades from view and instead we are placed in a position of imagining Union soldiers entering the Confederacy to destroy slavery—that they were somehow concerned about black people. Yet, what I continue to find in the record is case after case of Union officials making no distinction about the objective of the war and rounding up formerly enslaved people and shuffling them into former slave pens, barricading them in refugee camps, sending them on death marches to regions in need of laborers. I begin to lose my patience when various historians prop up the image of the Union army (or even Lincoln) as great emancipators when on the ground they literally turned their backs on children who starved to death; children who froze to death; children whose bodies were covered with smallpox. So, from where I stand, I see the Emancipation Proclamation as a central, important, and critical document that served a valuable purpose, but the sources quickly divert my attention to the suffering and sickness that defined freedpeople’s experience on the ground.

Do you see any parallels between the situation of post-Civil War freedpeople and the plights of currently distressed populations in the United States and abroad? What can we learn about public health crises, marginalized groups, etc.?

Yes, I do, but I would prefer to put this discussion on hold momentarily and simply say that we can see parallels today, right now. For example, there is a massive outbreak of the flu spreading across the country. Some are even referring to it as an epidemic. Yet in Harlem, New York, the pharmacies are currently operating with a policy that they cannot administer flu shots to children under the age of 17, which means that if a mother took time off from work and made it to Rite Aid, she can’t get her children their necessary shots. Given that all pharmacies in that region follow a particular policy, she and her children are stuck. In Connecticut, Kathy Lee Gifford of NBC’s Today Show relayed a similar problem, but she explained that she continued to travel throughout the state until she could find a pharmacy to administer her husband a flu shot. The mother in Harlem, who relies on the bus or subway, has to wait until Rite Aid revises its policy. Rite Aid is revising the policy now, as I write this response, but this means that everyday that it takes for a well-intentioned, well-meaning pharmacy to amend its rules, the mother in Harlem or mother in any other impoverished area must continue to send her children to school without the flu shot, where they remain susceptible to the virus.

In the Civil War records, I saw a similar health crisis unfold: people were not dying from complicated, unknown illnesses but rather from the failures of a bureaucracy, from the inability to provide basic medical relief to those in need, and from the fact that their economic status greatly determined their access to basic health care.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Jim Downs on the Emancipation Proclamation appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 1/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

African Americans,

social history,

*Featured,

Robert Williams,

Online Products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Black English,

cultural history,

Ebonics,

Oxford AASC,

Tim Allen,

“ebonics”,

“ebonics”—a,

aave,

languages—rubbed,

History,

US,

African American Studies,

educators,

journalists,

linguists,

Add a tag

By Tim Allen

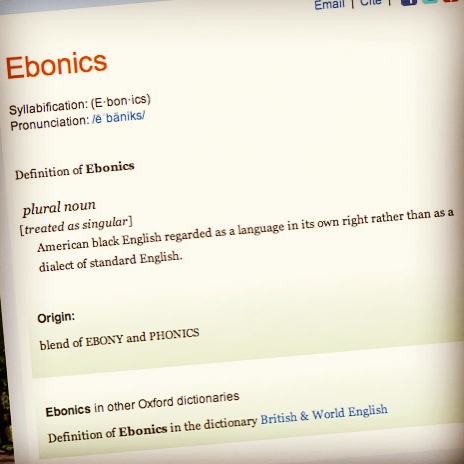

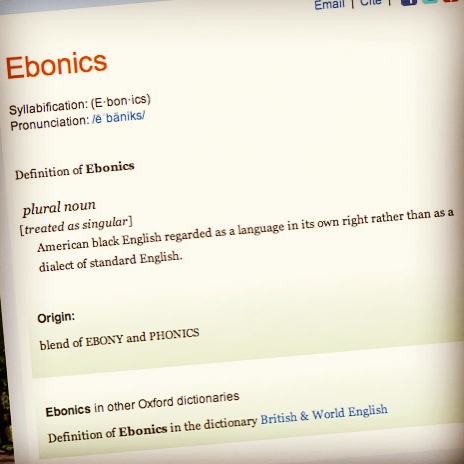

On this day forty years ago, the African American psychologist Robert Williams coined the term “Ebonics” during an education conference held at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. At the time, his audience was receptive to, even enthusiastic about, the word. But invoke the word “Ebonics” today and you’ll have no trouble raising the hackles of educators, journalists, linguists, and anyone else who might have an opinion about how people speak. (That basically accounts for all of us, right?) The meaning of the controversial term, however, has never been entirely stable.

For Williams, Ebonics encompassed not only the language of African Americans, but also their social and cultural histories. Williams fashioned the word “Ebonics”—a portmanteau of the words “ebony” (black) and “phonics” (sounds)—in order to address a perceived lack of understanding of the shared linguistic heritage of those who are descended from African slaves, whether in North America, the Caribbean, or Africa. Williams and several other scholars in attendance at the 1973 conference felt that the then-prevalent term “Black English” was insufficient to describe the totality of this legacy.

Ebonics managed to stay under the radar for the next couple of decades, but then re-emerged at the center of a national controversy surrounding linguistic, cultural, and racial diversity in late 1996. At that time, the Oakland, California school board, in an attempt to address some of the challenges of effectively teaching standard American English to African American schoolchildren, passed a resolution recognizing the utility of Ebonics in the classroom. The resolution suggested that teachers should acknowledge the legitimacy of the language that their students actually spoke and use it as a sort of tool in Standard English instruction. Many critics understood this idea as a lowering of standards and an endorsement of “slang”, but the proposed use of Ebonics in the classroom did not strike most linguists or educators as particularly troublesome. However, the resolution also initially characterized Ebonics as a language nearly entirely separate from English. (For example, the primary advocate of this theory, Ernie Smith, has called Ebonics “an antonym for Black English.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 21)) The divisive idea that “Ebonics” could be considered its own language—not an English dialect but more closely related to West African languages—rubbed many people the wrong way and gave a number of detractors additional fodder for their derision.

Linguists were quick to respond to the controversy and offer their own understanding of “Ebonics”. In the midst of the Oakland debate, the Linguistic Society of America resolved that Ebonics is a speech variety that is “systematic and rule-governed like all natural speech varieties. […] Characterizations of Ebonics as “slang,” “mutant,” ” lazy,” “defective,” “ungrammatical,” or “broken English” are incorrect and demeaning.” The linguists refused to make a pronouncement on the status of Ebonics as either a language or dialect, stating that the distinction was largely a political or social one. However, most linguists agree on the notion that the linguistic features described by “Ebonics” compose a dialect of English that they would more likely call “African American Vernacular English” (AAVE) or perhaps “Black English Vernacular”. This dialect is one among many American English dialects, including Chicano English, Southern English, and New England English.

And if the meaning of “Ebonics” weren’t muddy enough, a fourth perspective on the term emerged around the time of the Oakland debate. Developed by Professor Carol Aisha Blackshire-Belay, this idea takes the original view of Ebonics as a descriptive term for languages spoken by the descendants of West African slaves and expands it to cover the language of anyone from Africa or in the African diaspora. Her Afrocentric vision of Ebonics, in linguist John Baugh’s estimation, “elevates racial unity, but it does so at the expense of linguistic accuracy.” (Beyond Ebonics, p. 23)

The term “Ebonics” seems to have fallen out of favor recently, perhaps due to the unpleasant associations with racially-tinged debate that it engenders (not to mention the confusing multitude of definitions it has produced!). However, the legacy of the Ebonics controversy that erupted in the United States in 1996 and 1997 has been analyzed extensively by scholars of language, politics, and race in subsequent years. And while “Ebonics”, the word, may have a reduced presence in our collective vocabulary, many of the larger issues surrounding its controversial history are still with us: How do we improve the academic achievement of African American children? How can we best teach English in school? How do we understand African American linguistic heritage in the context of American culture? Answers to these questions may not be immediately forthcoming, but we can, perhaps, thank “Ebonics” for moving the national conversation forward.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post ‘Ebonics’ in flux appeared first on OUPblog.

By: ErinF,

on 1/21/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fulton,

Online Products,

fulton county,

Georgia,

History,

statistics,

US,

Sociology,

Data,

african american,

African American Studies,

census,

Martin Luther King Jr. Day,

Research Tools,

martin luther king jr,

county,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

social explorer,

Sydney Beveridge,

demography,

Add a tag

By Sydney Beveridge

Martin Luther King, Jr. was the legendary civil rights leader whose strong calls to end racial segregation and discrimination were central to many of the victories of the Civil Rights movement. Every January, the United States celebrates Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to honor the activist who made so many strides towards equality.

Let’s take a look at the demographics of the legendary man’s hometown then and now to see how it has (and has not) changed. King was born in 1929, so we’ll examine Census data from 1930, 1940, and the latest Census and American Community Survey data.

His boyhood home is now a historic site, situated at 450 Auburn Avenue Northeast, in Fulton County (part of Atlanta). In 1930, Fulton County had a population of 318,587 residents. A little over two thirds of the population was white (68.1 percent) and almost one third of the population was African American (31.9 percent). Today, the 920,581-member population split is nearly even at 44.5 percent white and 44.1 percent African American, according to 2010 Census data. Fulton’s population is more African American than the United States as a whole (12.6 percent), but not as as much as Atlanta (54.0 percent).

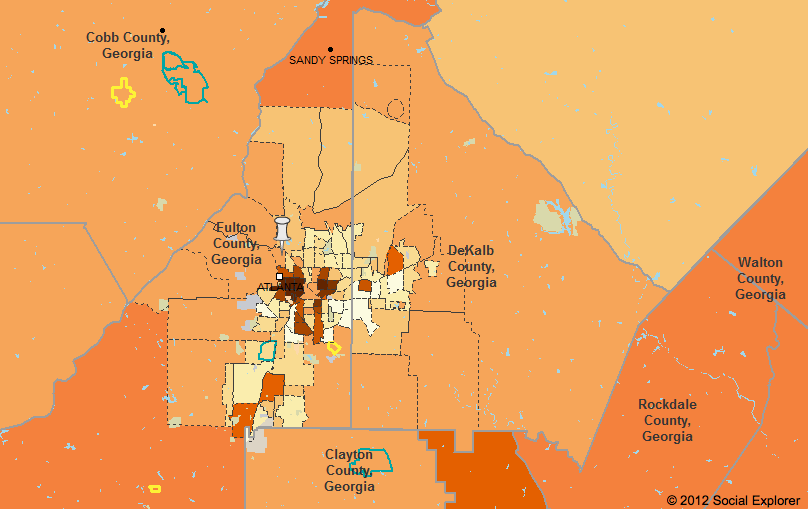

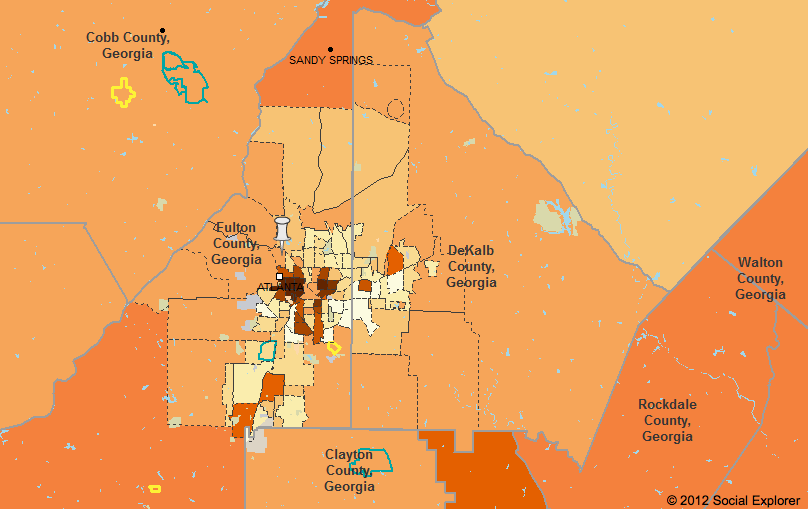

A closer look at 1940s Census data of the Atlanta area offers more detail about where the black and white populations lived. The following map shows the distribution of the black population in the Atlanta of King’s youth. Plainly, African Americans lived together, largely apart from whites.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 1940 (click map to explore)

For comparison, the following map shows where the black population lives today. Now the black population has expanded in the metro area, but still seems to be quite segregated.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 2010 (click map to explore)

Reflecting on a century after the end of slavery, King said in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

The quest for equal rights and freedoms made up part of a larger vision. In 1967, he spoke of aspiring for full equality at a speech at the Victory Baptist Church in Los Angeles:

Our struggle in the first phase was a struggle for decency. Now we are in the phase where there is a struggle for genuine equality. This is much more difficult. We aren’t merely struggling to integrate the lunch counter now. We’re struggling to get some money to be able to buy a hamburger or a steak when we get to the counter…

He went on to say that this would require a commitment of not only political initiative but also money: “It didn’t cost the nation one penny to integrate lunch counters. It didn’t cost the nation one penny to guarantee the right to vote. The problems that we are facing today will cost the nation billions of dollars.”

In 1968, King and other activists launched the Poor People’s Campaign, advocating for economic justice to address these imbalances in opportunity and resources. A few months later, he was assassinated.

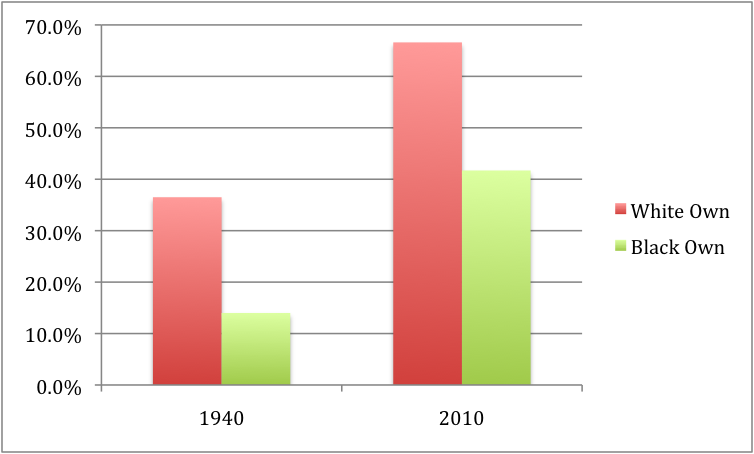

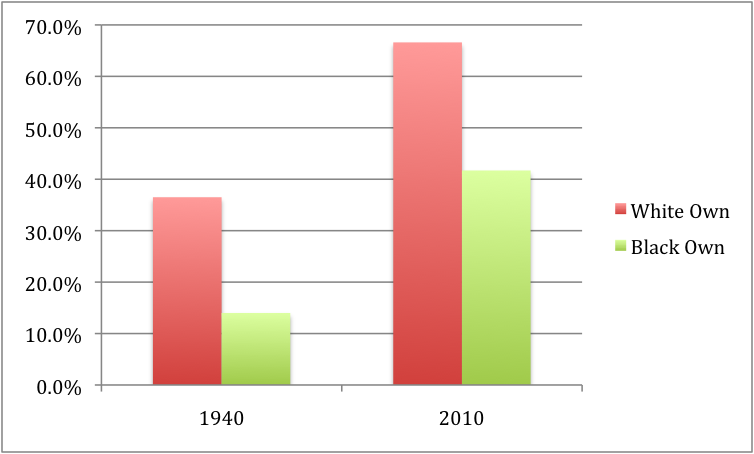

We can look at different socioeconomic indicators to measure the country’s progress towards equality. According to 1940 Census data, more than a third (36.5 percent) of housing units in Fulton County where whites lived were owner occupied, compared to less than a seventh (14.0 percent) of the housing units where African Americans lived.

Today, home ownership increased for both groups, but the gap remains. Two thirds (66.6 percent) of white households are owner-occupied, compared to two fifths (41.7 percent) of all black households.

Home Ownership Comparison in Fulton, GA, by Race

Let’s examine other measures of equality to see examples of additional gaps.

The unemployment rate is nearly twice as high among African Americans (17.9 percent) compared to among whites nationwide (9.5 percent). That gap is even more pronounced in Fulton County, where the unemployment rate for whites is 7.7 percent, while the unemployment rate for African Americans is 20.4 percent.

The percent of those living below poverty is also higher in the black community (27.2 percent) than in the white community (12.5 percent). While both groups are better off in Fulton County than the rest of the US, the poverty rate gap is even larger (8.2 percent among whites and 26.6 percent among African Americans in Fulton).

Similarly, while both groups are better educated in Fulton County compared to the rest of the US, nearly two thirds (62.4 percent) of white adults in the county have BA degrees or more, while just one quarter (25.3 percent) of the black population have the same level of education. The college attainment gap is 11.6 percentage points nationwide, but 37.1 percentage points in Fulton County.

While much progress towards freedom and equality has been made since King’s time, chronic gaps persist, even in his own backyard. The data show that 50 years after the “I Have a Dream Speech,” equal opportunity and socioeconomic status continue to lag behind equal rights.

Sydney Beveridge is the Media and Content Editor for Social Explorer, where she works on the blog, curriculum materials, how-to-videos, social media outreach, presentations and strategic planning. She is a graduate of Swarthmore College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. A version of this article originally appeared on the Social Explorer blog. You can use Social Explorer’s mapping and reporting tools to investigate dreams, freedoms, and equality further.

Social Explorer is an online research tool designed to provide quick and easy access to current and historical census data and demographic information. The easy-to-use web interface lets users create maps and reports to better illustrate, analyze and understand demography and social change. From research libraries to classrooms to the front page of the New York Times, Social Explorer is helping people engage with society and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Checking in on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream, with data appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 12/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

rosa,

boycott,

montgomery,

driver,

1955,

montgomery’s,

US,

american history,

African American Studies,

parks,

This Day in History,

civil rights movement,

the south,

African American History,

segregation,

rosa parks,

martin luther king jr,

*Featured,

higher education,

this day in world history,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

December 1, 1955

Rosa Parks refuses to change her seat

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks refused to move—and became the mother of the civil rights movement.

In 1955, strict segregation laws separated African Americans and whites in public settings across the South, including Parks’s home town, Montgomery, Alabama. That December evening, returning home from work, Parks sat with three other African Americans in a row just behind the fourteen whites in the front of the bus. Because the bus was full, a white man had to stand when he entered the bus. Under the South’s Jim Crow laws, whites sat and African Americans stood. The bus driver told Parks and the other three blacks to move to the back of the bus—the black section. The other three did, but Parks refused. The driver insisted, and she refused again. Faced with continued refusal, he used his powers under a city ordinance to arrest her. The driver summoned the police, and Parks spent the night in jail.

The arrest galvanized Montgomery’s African Americans. The local chapter of the NAACP had long resented the segregated buses and the drivers’ treatment of blacks; now they had a chance to act. The next day, a women’s council called for a boycott of the city bus system. African Americans by the thousands complied. By December 5, a new group—the Montgomery Improvement Association—was formed to coordinate the boycott. Inspired by young clergyman Martin Luther King, Jr., Montgomery’s African Americans kept up their boycott for more than a year, until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation on buses unconstitutional. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was one of the early triumphs of the civil rights movement. Parks later admitted her surprise: “I had no idea when I refused to give up my seat on that Montgomery bus that my small action would help put an end to the segregation laws in the South.”

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

By: Lauren,

on 7/29/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

adolescence,

J. D. Salinger,

African American Studies,

beat generation,

Holden Caulfield,

holden,

*Featured,

rebel,

60th anniversary,

a nation of outsiders,

grace elizabeth hale,

white middle class,

catcher,

Literature,

US,

catcher in the rye,

Add a tag

After 1951, if a person wanted to be a rebel she could just read the book. Later there would be other things to read—Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. But J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye was the first best seller to imagine a striking shift in the meaning of alienation in the postwar period, a sense that something besides Europe still needed saving.

By: Lauren,

on 5/16/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

bloody sunday,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

ku klux klan,

slave market,

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

birmingham,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

KKK,

massacre,

college students,

scottsboro,

NAACP,

Add a tag

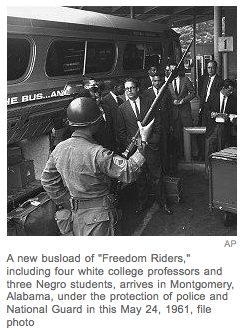

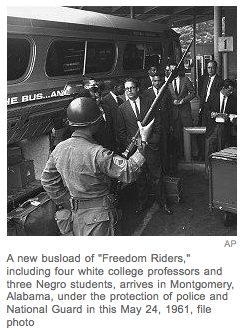

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 6–May 13: Nashville, TN, to Birmingham, AL

Day 6 started with a torrential downpour–the first bad weather of the trip–that prevented us from walking around the Fisk campus and touring Jubilee Hall and the chapel. So we headed south for Birmingham, passing through Giles County, the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, and by Decatur, AL, the site of the 1932 Scottsboro trial. We arrived in Birmingham in time for lunch at the Alabama Power Company building, a corporate fortress symbolic of the “new” Birmingham. We spent the afternoon at the magnificent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where we were met by Freedom Riders Jim Zwerg and Catherine Burks Brooks, and by Odessa Woolfolk, the guiding force behind the Institute in its early years. Catherine treated the students to a rollicking memoir of her life in Birmingham, and Odessa followed with a moving account of her years as a teacher in Birmingham and a discussion of the role of women in the civil rights movement. Odessa is always wonderful, but she was particularly warm and humane today. We then went across the street for a tour of the 16th Street Baptist Church, the site of the September 1963 bombing that killed the “four little girls.”

The rest of the afternoon was dedicated to a tour of the Institute; there is never enough time to do justice to the Institute’s civil rights timeline, but this visit was much too brief, I am afraid. Seeing the Freedom Rider section with the Riders, especially Jim Zwerg and Charles Person who had searing experiences in Birmingham in 1961, was highly emotional for me, for them, and for the students. As soon as the Institute closed, we retired to the community room for a memorable barbecue feast catered by Dreamland Barbecue, the best in the business. We then went back across the street to 16th Street for a freedom song concert in the sanctuary. The voices o

By: Lauren,

on 5/13/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

rides,

raymond,

anniston,

seigenthaler,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

sweet home alabama,

vanderbuilt,

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

nashville,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

college students,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 5–May 12: Anniston, AL, to Nashville, TN

Our fifth day on the road started with the dedication of two murals in Anniston, at the old Greyhound and Trailways stations. I worked with the local committee on the text, and I was pleased with the results. In the past, there was nothing to signify that anything historic had happened at these sites. The turnout of both blacks and whites was gratifying and perhaps a sign that Anniston has begun the healing process of confonting its dark past. The students seemed intrigued by the whole scene, including the media blitz. We then boarded the bus and traveled six miles to the site of the bus burning; we talked with the only local resident who was there in 1961 and with the designer of a proposed Freedom Rider park that will be built on the site, which now boasts only a small historic marker. I have mixed feelings about the park, but perhaps the plan will be refined to a less Disneyesque form. It was quite a scene at the site, but we eventually pulled ourselves away for the long drive to Nashville.

Our first stop in Nashville was the civil rights room of the public library, the holder of one of the nation’s great civil rights collections. Rip Patton gave a moving account of his life as a Nashville student activist. We then traveled across town to the John Seigenthaler First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, where John Seigenthaler talked with the students for a spellbinding hour. He focused on his experiences with the Kennedy brothers and his sense of the evolution of their civil rights consciousness. As always, he was captivating and gracious, and full of truth-telling wit. We gave the students the night off to experience the music scene in Nashville, while I and the Freedom Riders participated in a Q and A session following a screening of the PBS film. The theater was packed, and the response was very enthusiastic. It was great to see this in Nashville, a hallowed site essential to the Freedom Rider saga and the wider freedom struggle. On to Fisk this morning before journeying south to Birmingham and “sweet home Alabama.”

Raymond Arsenault is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History and and Director of Graduate Studies for the Florida Studies Program at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. You can watch his discussion with dire

Earlier this week, Melissa Harris-Perry, author of the forthcoming Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, was on her way into New Haven to meet with YUP about her book, tweeting as she made the journey; her visit even hit the blogosphere at Now Rise Books blog. In the book, Harris-Perry examines the cultural life expressed in literature, religion, music, images, and stereotypes that have formed black women’s political identity in America. Uniquely, she draws on political theory, surveys, and research that create a psychological portrait, as well, in order to fully illustrate the impact of how black women see themselves within the scheme of American politics. It’s not a book about voting or elected officials; it’s the past and contemporary story of what citizenship means for a vital part of America’s population, and how the rest of us perceive our sister citizens.

Earlier this week, Melissa Harris-Perry, author of the forthcoming Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, was on her way into New Haven to meet with YUP about her book, tweeting as she made the journey; her visit even hit the blogosphere at Now Rise Books blog. In the book, Harris-Perry examines the cultural life expressed in literature, religion, music, images, and stereotypes that have formed black women’s political identity in America. Uniquely, she draws on political theory, surveys, and research that create a psychological portrait, as well, in order to fully illustrate the impact of how black women see themselves within the scheme of American politics. It’s not a book about voting or elected officials; it’s the past and contemporary story of what citizenship means for a vital part of America’s population, and how the rest of us perceive our sister citizens.

You can read about Harris-Perry’s new book and see the rest of our Fall 2011 catalog, now available online. Oh, and if you don’t recognize the title, it comes from her column at The Nation, so you won’t be deprived of her acuminous insight before the book comes out.

In a similar vein, Carla L. Peterson’s contributions to the New York Times’ “Disunion” series on the Civil War have continued, with her newest piece on nineteenth-century African Americans, asking: “What Were the Women Doing?” Earlier this year, we published Black Gotham, in which Peterson explores her own heritage as part of the greater, largely untold history of blacks in New York before, during, and after the Civil War Reconstruction.

In a similar vein, Carla L. Peterson’s contributions to the New York Times’ “Disunion” series on the Civil War have continued, with her newest piece on nineteenth-century African Americans, asking: “What Were the Women Doing?” Earlier this year, we published Black Gotham, in which Peterson explores her own heritage as part of the greater, largely untold history of blacks in New York before, during, and after the Civil War Reconstruction.

By: Lauren,

on 5/12/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

Martin Luther King,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

KKK,

college students,

1961,

coretta scott,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

rides,

raymond,

anniston,

augusta,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 4–May 11: Augusta, GA, to Anniston, AL

As we left Augusta, I gave a brief lecture on Augusta’s cultural, political, and racial history–emphasizing several of the region’s most colorful and infamous characters, notably Tom Watson and J. B. Stoner. Then we settled in for the long bus ride from Augusta to Atlanta, a journey that the students soon turned into a musical and creative extravaganza featuring new renditions of freedom songs, original rap songs, a poetry slam–all dedicated to the original Freedom Riders. These kids are quite remarkable.

In Atlanta, our first stop was the King Center, where we were met by Freedom Riders Bernard Lafayette and Charles Person. Bernard gave a fascinating impromptu lecture on the history of the Center and his experiences working with Coretta King. We spent a few minutes at the grave sight and reflecting pool before entering the newly restored Ebenezer Baptist Church. The church was hauntingly beautiful, especially so as we listened to a tape of an MLK sermon and a following hymn. The kids were riveted.

Our next stop was Morehouse College, King’s alma mater, where we were greeted by a large crowd organized by the Georgia Humanities Council. After lunch and my brief keynote address, the gathering, which included 10 Freedom Riders, broke into small groups for hour-long discussions relating the Freedom Rides to contemporary issues. Moving testimonials and a long standing ovation for the Riders punctuated the event. Later in the afternoon, we headed for Alabama and Anniston, taking the old highway, Route 78, just as the CORE Freedom Riders had on Mother’s Day morning, May 14, in 1961. However, unlike 1961’s brutal events, our reception in Anniston, orchestrated by a downown redevelopment group known as the Spirit of Anniston, could not have been more cordial. A large interracial group that included the mayor, city council members, and a black state representative joined us for dinner before accompanying us to the Anniston Public Library for a program highlighted by the viewing of a photography exhibit, “Courage Under Fire.” The May 14, 1961 photographs of Joe Postiglione were searing, and their public display marks a new departure in Anniston, a community that until recently seemed determined to bury the uglier aspects of its past. The whole scene at the library was deeply emotional, almost surreal at times. The climax was a confessional speech b

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

greensboro,

college students,

1961,

American Experience,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

lunch counter,

lynchburg,

Add a tag

Raymond Arsenault was just 19 years old when he started researching the 1961 Freedom Rides. He became so interested in the topic, he dedicated 10 years of his life to telling the stories of the Riders—brave men and women who fought for equality. Arsenault’s book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, is tied to the much-anticipated PBS/American Experience documentary “Freedom Riders,” which premiers on May 16th.

In honor of the Freedom Rides 50th anniversary, American Experience has invited 40 college students to join original Freedom Riders in retracing the 1961 Rides from Washington, DC to New Orleans, LA. (Itinerary, Rider bios, videos and more are available here.) Arsenault is along for the ride, and has agreed to provide regular dispatches from the bus. You can also follow on Twitter, #PBSbus.

Day 1-May 8: Washington to Lynchburg,VA

Glorious first day. Student riders are a marvel–bright and engaged. Began with group photo in front of old Greyhound station in DC, where the 1961 Freedom Ride originated. On to Fredericksburg and a warm welcome at the University of Mary Washington, where James Farmer spent his last 14 years. One of the student riders, Charles Lee is a UMW student. Second stop at Virginia Union in Richmond, where the 1961 Riders spent their first night. Greeted by VU Freedom Rider Reginald Green, charming man who as a young man sang doo-wop with his good friend Marvin Gaye. Third stop in Petersburg, where former Freedom Rider Dion Diamond and Petersburg native led a walking tour of a town suffering from urban blight; drove by Bethany Baptist, where the 1961 Riders held their first mass meeting. On to Farmville and the Robert Russa Moton Museum, formerly Moton High School, the site of the famous 1951 black student strike led by Barbara Johns; our student riders were spellbound by a panel discussion featuring 2 of the students involved in the 1951 strike and later in the struggle against Massive Resistance in Farmville and Prince Edward County, where white supremacist leaders closed the public schools from 1959 to 1964. On to Lynchburg, where the 1961 Freedom Riders spent their third night on the road and where we ended a long but fascinating first day. Heade for Danville, Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte this morning. Buses are a rollin’!!!

Day 2-May 9: Lynchburg, VA, to Charlotte, NC

The second day of the Student Freedom Ride was full of surprises. We left Lynchburg early in the morning bound for Charlotte. We passed through Danville, once a major site of civil rights protests, where the 1961 Freedom Riders encountered their first opposition and experienced their first small victory–convincing a white station manager to relent and let three white Riders eat a “colored only” lunch counter.

Our first stop was in Greensboro, where we toured the new International Civil Rights museum, located in the famous Woolworth’s–site of the February 1, 1960 sit-in. This was my first visit to the museum, even though I was one of the historical consul

By: Lauren,

on 5/10/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

PBS,

US,

civil rights,

oprah,

bus,

violence,

African American Studies,

documentary,

Freedom Riders,

Raymond Arsenault,

*Featured,

freedom rides,

Audio & Podcasts,

racial justice,

ray arsenault,

whites only,

arsenault,

riders,

Add a tag

This article and audio component was produced by Adam Phillips of Voice of America.

The American South was a segregated society 50 years ago. In 1960, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation in restaurants and bus terminals serving interstate travel, but African-Americans who tried to sit in the “whites only” section risked injury or even death at the hands of white mobs. In May of 1961, groups of black and white civil rights activists set out together to change all that.

[See post to listen to audio]

They called themselves “Freedom Riders.” An integrated group of young civil rights activists decided to confront the racist practices in the Deep South, by travelling together by bus from Washington D.C. to New Orleans, Louisiana. Raymond Arsenault documents their trip in “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” He says many elder civil rights leaders denounced their strategy as a dangerous provocation that would set back the cause.