Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Conflict, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 90

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: cry, blink, stare, bodylanguage, gaze, conflict, fiction, writing, character, communication, craft, behavior, eyes, face, look, wink, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, History, Politics, cold war, Europe, martin thomas, regimes, torture, algeria, democratic, colonial, empire, *Featured, UKpophistory, fight or flight, decolonization, rebeliion, Add a tag

By Martin Thomas

Britain’s impending withdrawal from Afghanistan and France’s recent dispatch of troops to the troubled Central African Republic are but the latest indicators of a long-standing pattern. Since 1945 most British and French overseas security operations have taken place in places with current or past empire connections. Most of these actions occurred in the context of the contested end of imperial rule – or decolonization. Some were extraordinarily violent; others, far less so. Historians, investigative journalists and leading intellectuals, especially in France, have pointed to extra-judicial killing, systematic torture, mass internment and other abuses as evidence of just how dirty decolonization’s wars could be. Some have gone further, blaming the dismal human rights records of numerous post-colonial states on their former imperial rulers. Others have pinned responsibility on the nature of decolonization itself by suggesting that hasty, violent or shambolic colonial withdrawals left a power vacuum filled by one-party regimes hostile to democratic inclusion. Whatever their accuracy, the extent to which these accusations have altered French and British public engagement with their recent imperial past remains difficult to assess. The readiness of government and society in both countries to acknowledge the extent of colonial violence indicates a mixed record. In Britain, media interest in such events as the systematic torture of Mau Mau suspects in 1950s Kenya sits uncomfortably with the enduring image of the British imperial soldier as hot, bothered, but restrained. Recent Foreign and Commonwealth Office releases of tens of thousands of decolonization-related documents, apparently ‘lost’ hitherto, may present the opportunity for a more balanced evaluation of Britain’s colonial record.

In France, by contrast, the media furores and public debates have been more heated. In June 2000 Le Monde’s published the searing account by a young Algerian nationalist fighter, Louisette Ighilahriz, of her three months of physical, sexual and psychological torture at the hands of Jacques Massu’s 10th Parachutist Division in Algiers at the height of Algeria’s war of independence from France. Ighilahriz’s harrowing story helped trigger years of intense controversy over the need to acknowledge the wrongs of the Algerian War. After years in which difficult Algerian memories were either interiorized or swept under capacious official carpets, big questions were at last being asked. Should there be a formal state apology? Should decolonization feature in the school curriculum? Should the war’s victims be memorialized? If so, which victims? Although the soul-searching ran deep, official responses could still be troubling. On 5 December 2002 French President Jacques Chirac, himself a veteran of France’s bitterest colonial war, unveiled a national memorial to the Algerian conflict and the concurrent ‘Combats’ (using the word ‘war’ remained intensely problematic) in former French Morocco and Tunisia. France’s first computerized military monument, the names of some 23,000 French soldiers and Algerian auxiliaries who died fighting for France scrolled down vertical screens running the length of the memorial columns.

No mention of the war’s Algerian victims, but at least a start. Yet, seven months later, on 5 July 2003, another unveiling took place. This one, in Marignane on Marseilles’ outer fringe, was less official to be sure. A plaque to four activists of the pro-empire terror group, the Organisation de l’Armée secrète (OAS), carries the inscription ‘fighters who fell so that French Algeria might live’. Among those commemorated were two of the most notorious members of the OAS. One was Roger Degueldre, leader of the ‘delta commandos’, who, among other killings, murdered six school inspectors in Algeria days before the war’s final ceasefire. The other was Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, organizer of two near-miss assassination attempts on Charles de Gaulle, first President of France’s Fifth Republic. Equally troubling, it took the threat of an academic boycott in 2005 before France’s Council of State advised President Chirac to withdraw a planned stipulation that French schoolchildren must be taught the ‘positive role of the French colonial presence, notably in North Africa’.

One explanation for the intensity of these history wars is that few France and Britain’s colonial fights since the Second World War were definitively won or lost at identifiable places and times. The fall of the French fortress complex at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the climax of an eight-year colonial war over Vietnam’s independence from France, was the exception, not the rule. Not surprisingly, its anniversary has been regularly celebrated by the Vietnamese Communist authorities since then.

Elsewhere it was harder for people to process victory or defeat as a specific event, as a clean break offering new beginnings, rather than as an inconclusive process that settled nothing. Officials in British Kenya reported that the Mau Mau rebellion, rooted among the colony’s Kikuyu majority, was ‘all but over’ by the end of 1955. Yet emergency rule continued almost five years more. To the East, in British Malaya, a larger and more long-standing Communist insurgency was in almost incessant retreat from 1952. Surrender terms were laid down in September 1955. Two years later British aircraft peppered the Malayan jungle, not with bombs but with thirty-four million leaflets offering an amnesty-for-surrender deal to the few hundred guerrillas who remained at large. Even so Malaya’s ‘Emergency’ was not finally lifted until 1960.

In the two decades that followed, the Cold War migrated ever southwards, acquiring a more strongly African and Asian dimension. The contest between liberal capitalism and diverse models of state socialism became a battle increasingly waged in regions adjusting to a post-colonial future. Some of the bitterest conflicts of the 1960s to the 1990s originated in fights for decolonization that morphed into intractable proxy wars in which civilians often counted amongst the principal victims. In the late twentieth century France and Britain avoided the worst of all this. Should we, then, celebrate the fact that most of the hard work of ending the British and French empires was done by the dawn of the 1960s? I would suggest otherwise. For every instance of violence avoided, there were instances of conflict chosen, even positively embraced. Often these choices were made in the light of lessons drawn from other places and other empires. Just as the errors made sometimes caused worst entanglements, so their original commission reflected entangled colonial pasts. Often messy, always interlocked, these histories remind us that Britain and France travelled their difficult roads from empire together.

Martin Thomas is Professor of Imperial History at the University of Exeter. This post is partially extracted from Fight or Flight: Britain, France, and their Roads from Empire

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Two difficult roads from empire appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, editing, writing, character, behavior, action, how to, distance, ficiton, physical, body language, boundaries, personal space, reaction, touching, Add a tag

There are situations in which a character must control involuntary responses, especially if Dick is a spy, a cop, or pretending to be someone he isn’t. If faced with an angry mugger or screaming toddler, Dick's initial primordial response might be recoil. His body might tense to strike. If it is a mugger, he lets the punch fly, unless the mugger is holding a gun pointed at his head. If it is a toddler, Dick overrides the urge to strike and deals with it another way, unless he has poor self-control or the child is demon-possessed.

Some characters are touchy-feely types. An extrovert is more likely to be a hands-on kind of guy. An introvert hates being touched by people he doesn't know very well. A character who has been abused may not want anyone to touch him, no matter the reason, loving or otherwise.

Some families and cultures are big on physical displays of affection, others aren't. A character might hug every one he has ever met upon seeing them again. Others prefer a handshake or a bow. The reasons can be personality, culture, or life experience.

Make sure you tell the reader how the character feels about being touched. Is it a good thing or a bad thing?

What kind of caress, hug, or handshake was it?

Is Jane’s instinctive response to pull away when she knows she has to endure the hug?

These small conflicts illustrate character, reveal relationships, and make characters very uncomfortable at scene level.

Touch ignites an involuntary response, followed by a voluntary response, followed by a recovery. Illustrate the beats during critical encounters. The how and why are important. Was the touch appropriate or inappropriate? Tolerated or defended? Welcome or unwelcome?

Blog: Valerie Storey, Writing at Dava Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: The Great Scarab Scam, Conflict, Writing, Nanowrimo, Overtaken, Better Than Perfect, Add a tag

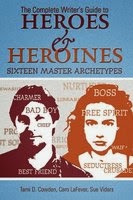

Just in time for NaNoWriMo: How well do you know your characters? By now you might be familiar with their physical features, their taste in evening clothes, and what they like to eat for breakfast, but what about their personality quirks and motivations?

One of my favorite writing how-to books to help uncover more about my characters' inner worlds and psyches is one by Tami D. Cowden, Caro LaFever, and Sue Viders:

Originally written for screenwriters, The Complete Writer's Guide to Heroes and Heroines, Sixteen Master Archetypes is a great tool for all writers, poets too, I can imagine! Based on the idea that there are 16 character "types" common to all fiction and mythology, the book is a great one to read just for fun as well as for research.

The other day I thought it would be interesting to re-examine where and how the three heroines from my published novels fit into the various categories. I also used the templates to evaluate the Pinterest boards I had created for these books: What kind of pins could I add to each? I started with:

The Great Scarab Scam

See The Great Scarab Scam Pinterest Board!

The Great Scarab Scam is my Egyptian mystery for young readers 8-12 years, so obviously there isn't the conventional male-female interaction you might find in a book for older readers. However, my main character, eleven-year-old Lydia Hartley, definitely falls into the category of "The Spunky Kid," and not just because of her age. Her other traits and story difficulties include:

- She's stuck between two brothers--one a little bit older and one quite a bit younger. Although neither of her brothers are particularly "heroic"

- She's a reader--and even enjoys doing homework!

- She's fiercely loyal to her father, a university professor and archaeologist.

- Loves history, especially ancient Egyptian history.

- She's curious about the world around her, but can be shy in social situations.

- She's brave, but a little reckless too.

- And she's very motivated when it comes to helping others.

Better Than Perfect

See the Better Than Perfect Pinterest Board!

My Young Adult novel set in New Zealand, Better Than Perfect, follows fourteen-year-old Elizabeth Haddon when she is sent from London to live with her wealthy relatives in Auckland. Elizabeth falls into "The Waif" category. She's:

- Lonely

- Unwanted

- The "poor relation"

- Insecure

- Smart, but without direction

- Prone to envy, especially when she continually has to make do with second best

- And she has a serious crush on an unconventional "bad boy."

Overtaken

See the Overtaken Pinterest Board!

Written for an adult audience, Overtaken includes some of my most complex characters, especially my heroine of Sara Bergsen. I had a bit of trouble discerning exactly which archetype she truly was, but in the end I decided she was "The Librarian."

- She's essentially a loner.

- Her chosen career as a portrait artist reflects her powers of observation and love of order. Abstract painting doesn't interest her in the least.

- Her wardrobe, at least in the beginning of the book, consists of practical pieces in black and gray--great for work!

- And this girl does loves work. She's disciplined and dedicated to deadlines.

- At the same time she takes risks because she is confident in her own ability to succeed.

- She's a reader--which has also led her to believe in the possibility of a happy ending.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, writing, character, plot, craft, dialogue, scene, tension, Add a tag

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, writing, characters, plot, communication, craft, dialogue, genre, argument, Add a tag

Let’s take a stroll back to beginning composition class to figure out how to illustrate a convincing change in character motivation.

In once scene Dick makes a point. In another scene Ted makes his counter point. Each encounter they have is an attempt to sway or force each other to adopt the opposite way of thinking. A different point is driven home each time.

Ted's scenes illustrate why he wants humankind destroyed. Ted may think Dick is a hopeless dreamer. Dick may drive home a few points that make Ted reconsider.

Dick's scenes address the reasons humanity should be saved. A few scenes could show him questioning his stance. Yet, it is Dick’s belief in the innate goodness of mankind that eventually gives him the tools or the access to stop Ted’s nefarious plan.

There will be friends that fight alongside Dick to save mankind. There may be a secondary character that is on the fence. Perhaps he or she encounters Sally and wonders if Dick is fatally naive. Jane could have a perilous dilemma of her own and her self-sacrifice illustrates Dick’s point that humanity is worth saving.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, characters, Andy Griffith, Don Knotts, Mayberry, foes, friends, writing, plot, craft, Add a tag

The protagonist was the widowed Sheriff Andy Taylor. He had a shrewd mind hidden behind a good-old-boy smile. That was his secret weapon. The antagonists always underestimated him. His role was that of caretaker to a town full of people too innocent to protect themselves. His weakness was that he was too nice, bordering on enabling.

I doubt storytelling will ever return to that level of innocence, but the world could use a little country comfort these days.

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Tension, Connection, Conflict, Writing Craft, Add a tag

One of the big rules we always hear about writing is that there must be conflict! Without conflict you have no tension, no stakes, and the story doesn’t go anywhere. Some say “without conflict you have no story” at all! Therefore we should always be on the look-out for the conflict in a scene and use it to make our stories more intense, emotional, and keep the boring-police away!

But, I have an admission. I’ve always had a problem with the idea that story revolves around conflict. I get nervous about how it limits what our stories can be about.

Don’t misread that comment. Conflict can be an important and useful storytelling tool, and there’s nothing wrong with using it. But… do we sometimes create conflict simply because we think we are supposed to? Are our lives defined by our conflicts? Is it all Man vs. Man, Man vs. Environment, Man vs. God, Good vs. Evil? Is it always about desire and obstacles and the conflicts that stand in our character’s way?

Is there not room for more?

This emphasis on conflict has always made me think of the fabulous quote in Diane Lefer’s essay, Breaking the Rules of Story Structure, where she says:

“The traditional story revolves around conflict – a requirement Ursula K. Le Guin disparages as the ‘gladatorial view of fiction.’ When we’re taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, we seem to choose by default to base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable” (63).

Janet Burroway adds to this discussion noting that “seeing the world in terms of conflict and crisis, of enemies and warring factions, not only constricts the possibilities of literature… [it] also promulgates an aggressive and antagonistic view of our own lives” (Writing Fiction, 255).

These quotes have always resonated with me. I find I’m not an action-and-conflict writer. But at the same time, I didn’t have any other guidepost to lead me. So, if it’s possible for stories to revolve around something other than conflict, what would that “something else” be?

Connection.

In Writing Fiction, Burroway goes on to discuss a narrative engine built on the human need for connection, rather than the clash of opposing forces. She says:

“A narrative is also driven by a pattern of connection and disconnection between characters that is the main source of its emotional effect. Over the course of a story, and within the smaller scale of a scene, characters make and break emotional bonds of trust, love, understanding, or compassion with one another. A connection may be as obvious as a kiss or as subtle as a glimpse; a connection may be broken with an action as obvious as a slap or as subtle as an arched eyebrow” (255).

This is an idea I can get behind!

A pattern of connection and disconnection is a narrative guideline that feels rooted in truth, human desire, and hope. It’s a guideline that – if you need it to – can lead to conflict, should that be where you want your story to go. For me, the need for connection, and the movement between connecting and disconnecting, exists in a deeper space than conflict alone. Good vs. Evil sits on the surface. Connection and disconnection is the pulse beneath the skin that motivates our characters. Can good or evil exist without it? This question excites me! The possibility of small actions energizing a story excites me!

I believe in the little moments.

I believe in the impact of an arched eyebrows and a subtle glimpse, may they have the power to grip our readers with as much intensity as a fight to the death.

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Tension, Connection, Conflict, Writing Craft, Add a tag

One of the big rules we always hear about writing is that there must be conflict! Without conflict you have no tension, no stakes, and the story doesn’t go anywhere. Some say “without conflict you have no story” at all! Therefore we should always be on the look-out for the conflict in a scene and use it to make our stories more intense, emotional, and keep the boring-police away!

But, I have an admission. I’ve always had a problem with the idea that story revolves around conflict. I get nervous about how it limits what our stories can be about.

Don’t misread that comment. Conflict can be an important and useful storytelling tool, and there’s nothing wrong with using it. But… do we sometimes create conflict simply because we think we are supposed to? Are our lives defined by our conflicts? Is it all Man vs. Man, Man vs. Environment, Man vs. God, Good vs. Evil? Is it always about desire and obstacles and the conflicts that stand in our character’s way?

Is there not room for more?

This emphasis on conflict has always made me think of the fabulous quote in Diane Lefer’s essay, Breaking the Rules of Story Structure, where she says:

“The traditional story revolves around conflict – a requirement Ursula K. Le Guin disparages as the ‘gladatorial view of fiction.’ When we’re taught to focus our stories on a central struggle, we seem to choose by default to base all our plots on the clash of opposing forces. We limit our vision to a single aspect of existence and overlook much of the richness and complexity of our lives, just the stuff that makes a work of fiction memorable” (63).

Janet Burroway adds to this discussion noting that “seeing the world in terms of conflict and crisis, of enemies and warring factions, not only constricts the possibilities of literature… [it] also promulgates an aggressive and antagonistic view of our own lives” (Writing Fiction, 255).

These quotes have always resonated with me. I find I’m not an action-and-conflict writer. But at the same time, I didn’t have any other guidepost to lead me. So, if it’s possible for stories to revolve around something other than conflict, what would that “something else” be?

Connection.

In Writing Fiction, Burroway goes on to discuss a narrative engine built on the human need for connection, rather than the clash of opposing forces. She says:

“A narrative is also driven by a pattern of connection and disconnection between characters that is the main source of its emotional effect. Over the course of a story, and within the smaller scale of a scene, characters make and break emotional bonds of trust, love, understanding, or compassion with one another. A connection may be as obvious as a kiss or as subtle as a glimpse; a connection may be broken with an action as obvious as a slap or as subtle as an arched eyebrow” (255).

This is an idea I can get behind!

A pattern of connection and disconnection is a narrative guideline that feels rooted in truth, human desire, and hope. It’s a guideline that – if you need it to – can lead to conflict, should that be where you want your story to go. For me, the need for connection, and the movement between connecting and disconnecting, exists in a deeper space than conflict alone. Good vs. Evil sits on the surface. Connection and disconnection is the pulse beneath the skin that motivates our characters. Can good or evil exist without it? This question excites me! The possibility of small actions energizing a story excites me!

I believe in the little moments.

I believe in the impact of an arched eyebrows and a subtle glimpse, may they have the power to grip our readers with as much intensity as a fight to the death.

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Luke Murphy, plot.obstacles, Dead Man's Hand, conflict, fiction, writing, motivation, craft, psychology, thriller, suspense, Add a tag

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: interiority, conflict, fiction, writing, genre, anxiety, anticipation, motive, Add a tag

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: interpersonal, conflict, characters, resentment, rage, motive, Add a tag

Blog: Game On! Creating Character Conflict (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, character, communication, dialogue, scene, obstacles, Add a tag

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, character, writing wednesday, internal, Add a tag

It's unfortunate because some ideas are best expressed in other languages. For example, sine qua non is a Latin legal term that we must translate into the more awkward, "without which it could not be." Sine qua non, captures the notion of something so necessary it's definitional.

I thought of that phrase when in a comment on Non-character Antagonists and Conflict, Anne Gallagher said:

Sometimes I think dealing with internal conflict makes a better story. Character driven narrative rather than plot driven.Anne is right: internal conflict is the sine qua non of story.

I'm also under the impression (in my genre I should clarify -- romance) there ALWAYS needs to be internal conflict for either the hero or heroine. One must always be conflicted by love.

Some of you, particularly if you equate internal conflict with navel gazing or whiny teenagers, may roll your eyes at that assertion. You may say, for example, that your story is about action and plot and your characters neither want nor need to take time off from dodging bullets to inventory their feelings.

I understand your objection, but answer this question: what's the common wisdom about characters and flaws?

If you said (thought) something along the lines of flawed = good (i.e., relatable and interesting), perfect = bad (i.e., boring or self-indulgent), you've been paying attention. (And if your answer includes, "Mary Sue," give your self bonus points).

So why do we like flawed characters?

Is it because they allow us to feel superior?

No. It's simply that flaws produce internal conflict. That's what people really mean when they say they find flawed characters more compelling than perfect ones.

Internal conflict gives us greater insight into character. There's nothing to learn from a perfect character: if we can't compare and contrast the thought processes that early in the character's development lead to failure and later to success, we can't apply any lessons to our own behavior.

Internal conflict also creates a greater degree of verisimilitude (because who among us doesn't have a seething mass of contradictions swimming around in their brain case).

Internal conflict and the expression of character flaws arises from uncertainty. If your characters are certain about how to resolve the problem, you don't have a story you have an instruction manual.

Ergo, conflict is the sine qua non of story.

That said, stories where conflicts at different levels reflect and reinforce each other are the most interesting because their resolution can be the most satisfying.

Deren Hansen is the author of the Dunlith Hill Writers Guides. Learn more at dunlithhill.com.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: inner, conflict, personal, writing wednesday, universal, Add a tag

As I played with the idea, I hit upon the exercise of characterizing the kinds of stories you get when the protagonist and antagonist come into conflict in terms of the nine combinations of the inner, personal, and universal dimensions.

In the following table, read from the protagonist's row to the antagonist's column. For example, if the protagonist's concerns are primarily internal and the antagonists are personal, you have a coming-of-age story or a story about establishing one's place and identity.

| Antagonist | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner | Personal | Universal | ||

| P r o t a g o n i s t | Inner | Psychological | Coming-of-age; Establishing one's place and identity | The socio-path or super man |

| Personal | Intervention and healing | Romance, mystery, thriller, speculative fiction, etc. (i.e., Most kinds of narrative conflict) | Rebels and underdogs | |

| Universal | Fatalist and extremists | Order vs. chaos (anti-rebellion) | Epic and political struggles | |

What I found most interesting about this exercise is that the primary locus of conflict in most stories falls in the center square (personal vs. personal). Many other stories fall on the diagonal (inner vs. inner or universal vs. universal). Asymmetric stories (e.g., personal vs. universal), are rarer.

I suspect this is because as social animals inter-personal conflict is the easiest to understand. Even if your story depends on another kind of conflict, your narrative will generally be most effective if you can put a face on the enemy for your readers. Your band of freedom fighters may be up against an empire, but your readers will identify with the dark lord who makes finding them his personal quest than with the legions of faceless soldiers he deploys. Similarly, readers will find a psychological struggle more accessible if there are other actors who symbolize the inner conflict.

It's also interesting to consider where different genres cluster in the matrix. For example, romance and mystery generally land in the upper left quadrant while speculative fiction and thrillers land in the lower right (with all, of course, overlapping in the middle).

Stories, clearly, aren't limited to one kind of conflict, so this analysis is only useful when we're considering the primary mode of conflict. Still, the moral of this story is that conflict is best when it's personal.

Deren Hansen is the author of the Dunlith Hill Writers Guides. Learn more at dunlithhill.com.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: organic, inevitable, writing wednesday, conflict, Add a tag

What is a contrived conflict?

In comic books, bad guys are bad because they're bad. Slap on a label like, "Nazi," or, "Terrorist," and your job is done. Other examples include oppressive clergy, greedy corporations, and government conspiracies. It's conflict by definition, which is the height of contrivance.

Another kind of contrived conflict is what I call irrational conflict: characters at loggerheads whose differences could be resolved with a rational, five-minute conversation. Romances are particularly liable to this kind of contrivance when the author can't think of a better reason to keep the leads apart. Yes, misunderstandings occur in real life, as do coincidences, but as a general rule (because you don't want your readers rolling their eyes) you're only allowed one of each.

Of course, it's not that some kinds of conflict are contrived and other are not. Any conflict where the reader sees the puppet strings, or worse, the puppeteer (author), is contrived. Readers need and want to believe that the conflict in the story arises organically from the mix of setting, plot, and characters, and that the conflict couldn't have played out any other way.

When I think about organic conflict, whether it arises from characters or plot, I imagine the parties to the conflict as forces of nature. Picture what happens when a surge of the restless sea meets the immovable cliff. Or when the speeding car meets the brick wall.

The most compelling conflict feels inevitable: notwithstanding everyone's best efforts, the collision occurs.

Unlike the watered-down food label, "natural," organic conflict is a much healthier, and a much more satisfying choice.

Deren Hansen is the author of the Dunlith Hill Writers Guides. Learn more at dunlithhill.com.

Blog: Dark Angel Fiction Writing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Editing and Adding Tension, Conflict, Add a tag

Yes, Score 1

No, Score 0

Both characters change, Score 2

2. Can conflict be resolved with a good, honest heart-to-heart between your characters?

Yes, Score 0

No, Score 1

3. Is it believable the one character (or both) would be leery of a relationship because of your conflict?

Yes, Score 1

No, Score 0

Ask this question to someone else who's read your story. If they say yes, add one bonus point.

4. Is conflict resolved because of sacrifice on one character's part?

Yes, Score 1

No, Score 0

If BIG sacrifice, Score 2

5. Must one character abandon their story goal?

Yes, Score 1

No, Score 0

6. Does conflict occur ONLY because one character does not trust the other character enough to have a heart-two-heart talk?

Yes, Score 0

No, Score 1

Score 9: Perfect SCORE!!!! Your conflict is right up there with Shakespeare or Lorraine Heath!

Score 5-8: Good job! Thorough, consistent, believable. Character development is entwined with conflict. Grisham could learn from you!

Score 0-4: You are too nice a person. Watch the evening news, go stand in line at the post office, or try to go through the express line at the grocery story with too many items. You must learn how to truly torment your characters properly.

You can visit Kathleen at www.KathleenOReilly.com

Blog: Valerie Storey, Writing at Dava Books (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Bride and Prejudice, Conflict, Fairy Tales, Endings, Jane Austen, Add a tag

I don't usually write movie reviews--in fact, I don't think I've ever written a single one, but I couldn't resist blogging about how much I enjoyed watching "Bride and Prejudice" two weekends back.

Made in 2004 and directed by Gurinder Chadhu of "Bend it Like Beckham" fame, the movie was one I've wanted to see for some time but never seemed to get around to it. Recently, however, I've been on a bit of a Jane Austen tangent, so when I was at the library the other day and saw the film on the DVD shelf, I knew it was the right time for a little fairy tale fantasy.

It turned out to be a serendipitous choice--I absolutely LOVED this movie. For those of you who haven't seen it, it's a modern-day version of Pride and Prejudice set in rural India. Aishwarya Rai (aka "the most beautiful woman in the world") and Martin Henderson play the parts of Lalita Bakshi and Will Darcy, or as we might recognize them from the original Austen text: Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy.

Moving the story up a few centuries and taking it from the English countryside to Amritsar was an incredibly clever interpretation of a much beloved classic. The Bakshi family was the perfect remake of the Bennets; Will and Lalita were just as conflict-ridden as their original counterparts; and the chemistry between all the characters--including Jaya (Jane) and Mr. Balraj (Bingley) was almost better than the book!

I've always been a big fan of Bollywood: lots of bling, embroidered silk veils and saris, singing and dancing for no reason whatsoever, dreamy couples who seem to have all the money and time they need to fly around the world to gaze wistfully at sunsets and each other, and of course the 3-hankie happily-ever-after ending. Bollywood is the ultimate escapist, love-conquers-all movie moment. "Bride and Prejudice" was no exception.

Which got me thinking about what makes a great romance book or movie. And this is what I've come up with: two strong, intelligent characters overcome their very real differences so they can learn to work together. Yep, it's all about work. Kissing is the easy part. Getting to the altar takes courage. And a lot of singing and dancing.

I've always thought Pride and Prejudice is essentially a story about marriage. The relationship between the parents--the Bennets in Pride, and the Bakshis in Bride--truly intrigues me. Mismatched on the surface but made for each other; their bond is what has made Jaya and Lalita the heroines they are. My favorite line from "Bride and Prejudice" is when a distraught Mrs. Bakshi is scolding her daughters on being so concerned about marrying for love. She turns and points to a sheepish-looking Mr. Bakshi. "Where was love in the beginning?" she chides. Where indeed? And yet here she is, with four pretty girls, a home of her own, and a husband who obviously cares for her. Awww. As the girls sing after dinner with the endearingly awful Mr. Kholi: "No Life Without Wife!"

Blog: Playing by the book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Conflict, Friendship, Cats, Houses, Colours, Jenni Desmond, Add a tag

It’s been a while since I fell in love at first sight, but that’s precisely what happened when I saw the front cover of Red Cat, Blue Cat by debut author/illustrator Jenni Desmond.

The cats’ gorgeously grumpy expressions, the boldness of the image as a whole, the delicate detailing of the birds in flight – it made me catch my breath, nod and smile.

And on turning the pages my sense of excitement and delight only grew. Red Cat, Blue Cat (published later this month in the UK) turns out not only to be beautiful but also witty, original, and jam-packed with joie de vivre; a gentle and humorous exploration of identity, envy and friendship.

Red Cat is fast and bouncy whilst Blue Cat is clever and creative. They share a house but the only other thing they have in common is a secret wish: to be more like the other. Try as they might, all they end up doing is fighting and getting in a big mess. Finally it dawns on them that not only is imitation really the sincerest form of flattery, but happiness also comes more easily if your comfortable with the skin you’re in. A friendship is born based on acceptance and appreciation of difference.

Desmond tells a great story, full of giggles (regular readers of my blog should be delighted to know there are more pants on heads!) as well as having a more thoughtful side. Her illustrations are clean, fresh and eyecatching. Definitely a talent I hope to see much more of in the future.

Inspired by the terraced housing on the title page of Red Cat, Blue Cat we set about creating our own street scene with cats.

We each had a bunch of plain white postcards onto which we drew house fronts. We use origami paper for the roof tiles and added telegraph poles and wires made from barbecue skewers and yarn, and chimney smoke made from toy stuffing fibre.

M added TV aerials made from paper clips and passport photo booth images of us looking out of windows.

I particularly like the bird nesting in the chimney of the house below, and the bicycle in front on the road.

Whilst making our street collage we listened to:

Other activities which would work well alongside Red Cat, Blue Cat include:

So what’s the last book you judged by its cover? Was it one you didn’t read because of the way it looked, or one you bought straight off because the front cover spoke to you?

Blog: WOW! Women on Writing Blog (The Muffin) (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plot, plotting, crafting plot, Elizabeth King Humphrey, Conflict, Add a tag

|

| My illustration is intentionally messy. Many writers would give the middle-end a steeper slope. Credit: Elizabeth Humphrey |

Now that school is back in session, I’m getting geared up to play editor-mom. That is, reading drafts of stories and reports, trying to be supportive without, well, rewriting the some of the work. I love reading the beginning stories, but it continues to astound me that we read countless stories to children, but if you ask them to tell you what happened in a story, the storyline seems bland or flat. The stories don’t seem to go anywhere.

Often the flat story is how the children process the stories, as well--even if the story involves a boy, his dog, kidnappings, and international spies. If I ask my children what happened in TinTin (the movie or the comic books), I may get the response about the cute dog and nothing about the story’s plot.

The plot of a story may be compelling, but it is not necessarily what we notice all the plot points as we learn about storytelling. (After all, when was the first time you diagrammed a novel’s plotline?)

As we develop as writers and readers, we start learning about plotting our stories. It helps us to discern what writers we like—fast-moving books generally have tightly written plots with conflicts that crackle from the pages. But even so, plots can still be a confusing muddle.

How do you plot a story? How do you ensure the plot points are strong and build to the middle and bring the story to a good conclusion? Take your time.

Often the stories our children tell—and ones that we attempt to write—are missing the dramatic question and the conflicts that advance a plot. The question and conflicts help to tease out what the story is really about and helps to answer the question: “So what?”

Work those out as you work with your draft. It’s not a one-time happening, but something that is massaged along your novel or short story’s journey.

Sure, the cute dog is important, but he’s vitally important because he and his actions help move the plot along.

Do you sketch out your plot points in an arc in the beginning, middle or end of writing your story's first draft?

Elizabeth King Humphrey is a writer and editor living in North Carolina. She enjoys using various colored pens to plot her novel’s storyline, but sometimes gets carried away and starts doodling instead.

Blog: Plot Whisperer for Writers and Readers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, memoirs, character transformation, Thematic Significance, suspense, screenplays, sensory details, relationships in novels, urgency and curiosity, use of emotion, tensions, Add a tag

Do you writes in layers, one or two layer per draft? Or do you write all the layers of your novel, memoir, screenplay at once?

Do you writes in layers, one or two layer per draft? Or do you write all the layers of your novel, memoir, screenplay at once?

And what are all these layers, you ask?

Emotion: evoking a range of emotions -- positive and negative -- in the reader through the characters' show of emotion.

Conflict, tension, suspense, urgency and curiosity: shaping the dramatic action to keep the reader turning the pages to learn what happens next.

Character transformation: showing a flawed character change overtime spiritually, emotionally, physically, or mentality or all of the above.

Thematic significance: bringing meaning to the story.

Relationships: revealing the complexity and intimacy of the characters in relationship to each other.

Sensory: using senses -- auditory, visual, tactile, taste, smell -- to transport the reader deeper and deeper into the story world.

1) Read The Plot Whisperer: Secrets of Story Structure Any Writer Can Master (The companion workbook is coming this summer and available for pre-order now ~~ The Plot Whisperer Workbook: Step-by-step Exercises to Help You Create Compelling Stories)

2) Watch the Plot Series: How Do I Plot a Novel, Memoir, Screenplay? on YouTube. Scroll down on the left of this post for a directory of all the steps to the series. 27-step tutorial on Youtube

3) Watch the Monday Morning Plot Book Group Series on YouTube. Scroll down on the right of this post for a directory the book examples and plot elements discussed.

For additional tips and information about the Universal Story and plotting a novel, memoir or screenplay, visit:

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, novels, scene, fight, Add a tag

You are thinking you need a fight scene in your novel. The most important question is “Why?” Your novel and the specific situation in a particular scene must demand some sort of physical interaction between characters. But don’t think that the physical is the end-all of the scene; instead, a fight scene is an opportunity to reveal character as the characters interact in a physical way. As with any scene, there should be a beginning, middle and end and somewhere in there, a pivot point where the story changes direction.

Let’s Fight: Basics of a Fight Scene

First, a fight scene must move the novel or story forward. The outcome of the fight must matter on a large enough scale, and yet on a small enough scale, too. That is, not so big that the story ends abruptly, but enough that something important changes. What is at stake (other than dying) and why is it important to the story?

It’s all about character. The stakes of the scene should be rooted in character, the fighters and/or the observers. It must reveal something about your character as the scene progresses. (beliefs, what is worth fighting for, fears, cowardice, courage, what the character is willing to do and what s/he won’t do, etc.). It can’t just be whacking each other over the head. It must matter to the story and to the character, both internal and external arcs.

Make it hard for the characters. Give the characters equal skills, so the fight relies on character qualities for its outcome. Be realistic here. For example, a child or teen may not be as strong as a burly man, but they may be faster. Think about how different skills can offset the opponent’s strength. You’ll ultimately have to figure out how the underdog might defeat a stronger foe; but it must be hard and must be believable.

Final Showdown. Hero must barely survive and must run out of options as the fight progresses.

In the final showdown, the Hero must go beyond his normal abilities, face some fear or do the unthinkable or impossible to survive. This isn’t a waltz. It’s a waltz of death. Maybe the death of a hope, a fear, an alternative, a love.

How to Write a Fight Scene

List possible actions. If you are doing a sword fight, they can thrust, jab, parry, dodge and so on. Are there alternate weapons, alternate settings, alternate methods? If so, list these and then rank them in order of danger or what is at stake. You’ll start the fight with the gentlest, most benign fighting and move toward more deadly methods. Rank not just weapons, but also settings and other methods of fighting. For example, settings may be more dangerous if the fight is in a swamp (deadly footing), a rainstorm (visibility and footing), an alley (dark, close quarters), etc. Be sure to consider all variables and start with the easiest and work up to the hardest. It may mean that one fight escalates through all these stages, or it may mean that early fights in a series of conflicts are easy lea

Add a CommentBlog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, plot, how to, what next, What if, complications, develop, Add a tag

While I am struggling with plot, the main question I am asking is “What if?”, closely followed by “What next?”

What if?

Creative plots focus on an unexpected combination of events that somehow manage to mesh together at the end when all is revealed. Plots can be about vengeance, catastrophe, love & hate, chase, grief & loss, rebellion, betrayal, persecution, self-sacrifice, survival, rivalry, a quest or an ambition. They can be complicated or enhanced by criminal action, searching, honor & dishonor, rescue, suspicion, murder, suicide, adventure, mystery, suspense, material well-being, bucking authority, making amends, deception, conspiracy, rivalry, or mistaken identity.

Creative plots focus on an unexpected combination of events that somehow manage to mesh together at the end when all is revealed. Plots can be about vengeance, catastrophe, love & hate, chase, grief & loss, rebellion, betrayal, persecution, self-sacrifice, survival, rivalry, a quest or an ambition. They can be complicated or enhanced by criminal action, searching, honor & dishonor, rescue, suspicion, murder, suicide, adventure, mystery, suspense, material well-being, bucking authority, making amends, deception, conspiracy, rivalry, or mistaken identity.

The general categories of plots and their complications are simple to identify. What is hard is applying these to your story. The key attitude here is “What if?” What if I wrote this as a story of rebellion? What if there’s a strong sibling rivalry and also a case of mistaken identity because they are twins?

Don’t like the answer to that “What If?” Try a different one.

What if this is a story of survival, with questions of honor and dishonor central to the main character? Throw in a chase and survival just for good measure.

Do you like this “What If” better? Why? Could you combine parts of each?

It’s brainstorming, but always within a tight boundary of what is possible when we write fiction.

What Next?

The second basic plot question is “What Next?” Plots happen in sequential order and if you can build in a cause-effect relationship, the plot is stronger. Once you start to recognize the conflict and complications for your plot, you can start to build a chronological order. At no point, do you have NO conflict; it’s just a matter of slotting in conflict in the most dramatic way possible.

The “What If?” works here, too. What if the first act has a case of mistaken identity? Would that lead to someone being wrongfully dishonored? And would that lead to a criminal action, maybe stealing money to buy back a reputation?

|

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: scene cut, conflict, characterization, details, show don't tell, novel revision, strong verbs, Add a tag

Reread your story.

Does it surprise you at any point? Does it keep YOUR interest?

Recently I reread a story that I had not read for a while, long enough for me to start to be fuzzy on details. Here are some things that struck me.

“To see Mrs. Lopez’s smile was to understand the amazing abilities of a mouth: her mouth was as wide as a whale’s and everyone knew her business–and the silver in her molars.”

“My heart went skippety-skip. A sideways glance: Marj’s freckles looked friendly enough, even if she wasn’t smiling. But she didn’t answer the question, didn’t say she was my mother.”

What are you noticing afresh in your reading these days?

|

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, writing advice, Writing, source of conflict, Add a tag

|

| Erin Shakespear |

Conflict. Oy...we need a lot of the stuff, right? In our books anyways...in my living room, between the wee natives, not so much.

The Proper Care & Feeding of Conflict

#3: Load It Up

You could give your character one conflict. But why not throw in all three? A conflict internally, something he wants desperately, a conflict between those around him, with a friend or family member and a conflict within his environment. Oooooh, that would be a whole lo

View Next 25 Posts

.jpg)

Hi Ingrid,

An argument could be how ‘conflict’ is defined, but I see your point.

I am just making notes for my next project, which will be quite a dramatic piece, and your post made interesting reading.

I am also one for writing a story in the way that the story needs to be written, and not by sticking to rules or ‘ancient’ guidelines that may not be suited to the project.

Great article!

I think the notion of “conflict” must be taken loosely. Disconnection represents a type of conflict, if only a passive one. So I think your wording is just a synonym of the old “conflict” method. It’s a question of spectrum, I guess.

James,

I completely agree. So much depends upon how you define a specific term. For me personally, I always associated conflict with creating physical action (fights, action scenes, or “shit happening”). It always had sense of combat in my mind. I was excited to find a way to look at narrative drive that came from something quieter.

I also agree that a story will tell you how it should be told. Guidelines are great, but sometimes they want to strangle the heart out of your story (particularly when you let to many other voices come in and tell you how your story should be written).

Glad to hear this post got you thinking!

Wonderful post. I see Mr. Roses’s point. The ebb and flow of characters connecting or the lack of connection can be defined as conflict. It is ultimately the connection characters have with one another that resonates most with me. I like the push-pull of the ride getting there though. I’m glad I read your post. Very insightful.

Thanks for this post, Ingrid. It deepens the discussion of desire as well as of conflict — not just the characters’ desires, but what we want for them, and why. It also made me think of brilliant John Cleese, and his idea that the only difference between comedy and tragedy is whose side you’re on.

Claudia Johnson has written on this as well, in her CRAFTING SHORT SCREENPLAYS THAT CONNECT. Johnson’s point is that a drive to connect is often what motivates characters to action. Conflict arises from the obstacles they encounter in their quest to make that connection.

Your take on the smaller moments and gestures deepens the point. Conflict and connection do go hand in hand.

Stephanie – There’s something deliciously interesting to me in the idea of “passive conflict.” I’m not sure the implications of that at this moment, but I shall sit and ponder it!

Kathy,

I absolutely think conflict and connection go hand in hand. I think conflict alone can be hollow. I find most writing “rules” or “guidelines” don’t exist in a vacuum. Every writing choice interacts and influences the next.

It seems to me you are talking about tension. Donald Maas refers to tension on every page. The raising of an eyebrow or refusal to respond to another causes this tension. Which could also be considered conflict on a smaller scale. This keeps a reader turning pages, as the reader doesn’t know when all of this eyebrow raising will come to a head.

I sooooo love this post. Love the aspect of connection. I sometimes find myself pushing to add a conflict that doesn’t really fit the character, but pushes my plot agenda. I think that’s what you mean, right, by conflict being hollow?

Thoughtful post! And you’ve given voice to things that have rattled around in my brain for a while. I like writing for middle-grade, and the question of conflict weighs heavily for me in this realm. I don’t want the stakes to be too high. So the conflict I focus on is less good vs. evil, big scale stuff. I think I’d agree with you that connection is what drives me more. Thanks for the post.