new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: civil war, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 95

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: civil war in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Reading this story, my heart is in my throat.

The Battle of Gettysburg, Day 2, July 2nd, 1863.

“The scene is the center of the American line. Most of the attacks on the flanks have been repulsed by now, or nearly so, and the sun is near to setting. The American lines are now almost set into the famous ‘fish-hook’ formation that one can find on so many maps. But the operative word is ‘almost.’

“In the center, there is a gap…”

The writer is Lt. Col. Robert Bateman, and his recounting of the events in the weeks leading up to Gettysburg has had me enthralled for days. I’ve followed him from Fredericksburg, Virginia—the town, incidentally, where I graduated from college, and where I met Scott—north to Pennsylvania, his posts spanning the months of June and July, 1863, just over 150 years ago. I don’t particularly want to be in Gettysburg right now; my attention ought to be far to the south, in Alabama. But I can’t look away. Lt. Col. Bateman’s account is riveting.

“In the center, there is a gap because one American Corps commander took it upon himself to move well forward earlier in the fight. The rebels are now finishing crushing that Corps. But ever since that audacious Union Corps commander created that gap in the first place, a succession of recently arriving units have been fighting to keep the middle from collapsing. Now, as the sun sets over Seminary Ridge, the game is almost over. But there is a half-mile opening in the remaining American line, and two whole rebel brigades are headed straight to it.”

You’ll have to read the entire post to get the full thrust of what’s on the line in this moment—heck, you ought to read the whole series—but some of you will understand why this next passage made me gasp.

The American Corps commander now in charge of the section of the line closest to the hole, a fellow named Hancock, sees what is about to happen. The rebels are moments away from breaking the center of the Union line. His own Corps line ends several hundred yards to the north. The next American unit to the south is a quarter mile away. Hancock can see the reinforcements he has called for, as can others on the crest of the hill. Those troops are marching at full speed up the road. By later estimates, the relieving troops are a mere five minutes away from the ridgeline. But the Confederates are closer.

I talked about psychology yesterday. I wrote about how sometimes something that can only be described as moral ascendency (or perhaps morale ascendency) can make it possible for a smaller force to defeat a larger force — first emotionally, then physically. Rufus Dawes and his 6th Wisconsin Infantry pulled that off on the First Day, albeit at a horrendous cost. General Hancock understands in an instant the bigger picture. This is not some small slice of the field. He sees that if the rebels make it to the ridge, they might gain the psychological advantage over the whole Army of the Potomac, much of which is still arriving. So the rebels must be stopped. Now. Here.

And now, what I am about to describe to you transcends my own ability to explain. Hell, it is beyond my own understanding, and I have been a soldier for decades.

General Hancock sees a single American regiment available. But, though it is a “regiment,” this is in name only at this point. A “regiment,” at the beginning of the war, would be roughly 1,000 men. Before Hancock stand 262 men in American blue. Coming towards them, little more than 250 yards away now, are two entire brigades of rebels. Most directly, half of that force — probably about some 1,500 men from a rebel brigade — were coming dead at them. Perhaps a thousand more, at least two entire additional regiments, were on-line with that main attack, though probably unseen by Hancock. But what does that matter? The odds were, already, beyond comprehension.

“My God! All these all the men we have here…What regiment is this?” Hancock yelled.

“First Minnesota,” responded the colonel, a fellow named Colvill.

First Minnesota.

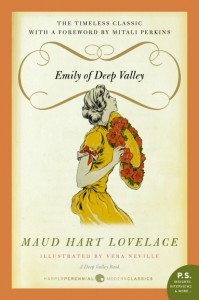

That’s right, Lovelace readers. The very regiment Emily Webster’s grandfather fought in, the one Carney’s Uncle Aaron (her great-uncle, surely) died in—in that charge on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

That’s right, Lovelace readers. The very regiment Emily Webster’s grandfather fought in, the one Carney’s Uncle Aaron (her great-uncle, surely) died in—in that charge on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

“When Colonel Colville told us to charge,” [Grandpa] said, nobody ran out on that field any faster than Aaron Sibley.”

“You ran fast enough to get a bullet through your arm.”

“Only winged, only winged,” he answered impatiently. “It might have been death for any one of us.”

It was for a good many of them, Emily remembered. She had heard her grandfather say many times that only forty-seven had come back out of two hundred and sixty-two who had made the gallant charge.

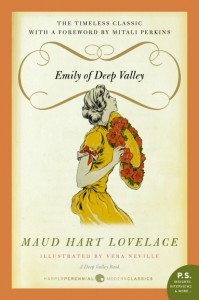

—from Emily of Deep Valley by Maud Hart Lovelace

Every single man of the 1st Minnesota,” writes Lt. Col. Bateman,

“placed as it was at the crest of the gentle slope, could see what was going on. All of them were veterans, having fought since the beginning of the war. Each of them understood the exact extent of what they were being asked to do by General Hancock. And, it would appear, that they all understood why.

“On this day, at the closing of the day, there was no illusion that they might win. There was not any thought that they could throw back a force more than seven or eight times their own size. Not a one of them could have entertained the idea that this could end well for them, personally.

“I suspect, though of course nobody can actually ‘know,’ that there was only a silent, and complete, understanding that this thing must be done. So that five minutes might be won for the line and the reinforcements and that their widows and children might grown up in a nation once more united, they would have to do this thing. Then, as men, the 262 men of the 1st Minnesota followed their colonel as he ordered the advance, leading them himself, from the front.

“They charged, with fixed bayonets, to win 300 seconds for the United States. Union and Confederate sources agree on this next point: There was no slacking, no hesitation, no faltering. The 1st Minnesota charged, en masse, at once alone and together. One hundred and fifty years later, those 300 seconds they then won for the United States have proven timeless. Because it worked. They threw a wrench into the rebel attack, stalling it, before the inevitable end.

“And, as Fox’s Compendium pointed out in cold, hard numbers, it only cost 82 percent of the men who stepped forward.”

Grandpa Webster and Aaron Sibley are fictional characters, but they are based on real people, just as Emily and Carney were. In the afterword to HarperPerennial’s 2010 edition of Emily of Deep Valley, Lovelace historian Julie A. Schrader tells us that Grandpa Cyrus Webster represented a man named John Quincy Adams Marsh, the grandfather of Maud’s classmate Marguerite Marsh, the “real” Emily. He was not, however, a Civil War veteran. Schrader writes,

“Maud appears to have based Grandpa Webster’s experiences on those of Captain Clark Keysor (Cap’ Klein)…. General James H. Baker, a veteran of the Dakota Conflict and the Civil War, was the basis for the character of Judge Hodges. In 1952 Maud wrote, ‘Old Cap’ Keysor and General Baker used to visit the various grades on Decoration Day to tell us about the Civil War…’”

Emily is, as I’ve often mentioned, not only my favorite Maud Hart Lovelace book, it’s one of my favorite novels period. Grandpa Webster is very real to me. I can’t describe my astonishment to find him there, suddenly, in Lt. Col. Bateman’s account, rushing unhesitatingly toward that gap in the line. 262 men made the charge. 47 survived. One of them was Cap’ Clark Keysor, who visited Maud’s school classrooms and told her stories she never forgot. Nor shall I.

***

For Lt. Col. Bateman’s entire Gettysburg series, click here.

For more background on the real people who inspired Maud Hart Lovelace’s characters, I highly recommend Julie Schrader’s book, Maud Hart Lovelace’s Deep Valley.

Related posts:

Why I love Carney

Why I love Emily

A Reader’s Guide to Betsy-Tacy

By: AlanaP,

on 2/8/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

movies,

film,

hollywood,

Racism,

silent film,

Lincoln,

civil war,

Cullen,

cinema,

*Featured,

american cinema,

D.W. Griffith,

TV & Film,

ku klux klan,

Spielberg,

Arts & Leisure,

Birth of a Nation,

Jim Cullen,

Sensing the Past,

griffith,

griffith’s,

Add a tag

By Jim Cullen

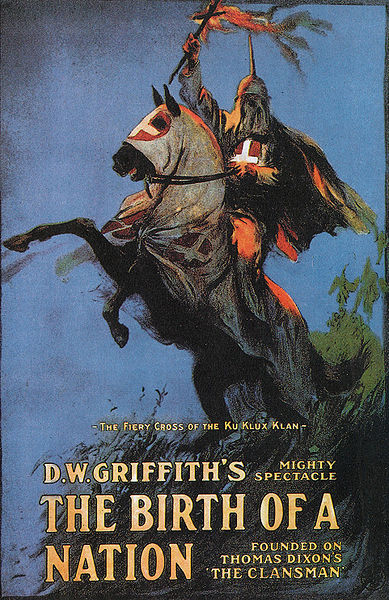

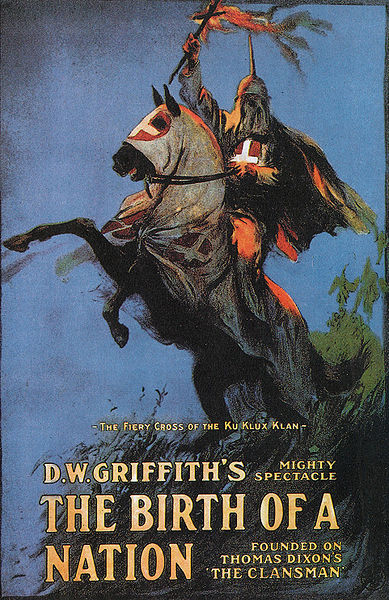

Today represents a red letter day — and a black mark – for US cultural history. Exactly 98 years ago, D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation premiered in Los Angeles. American cinema has been decisively shaped, and shadowed, by the massive legacy of this film.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

D.W. Griffith (1875-1948) was one of the more contradictory artists the United States has produced. Deeply Victorian in his social outlook, he was nevertheless on the leading edge of modernity in his aesthetics. A committed moralist in his cinematic ideology, he was also a shameless huckster in promoting his movies. And a self-avowed pacifist, he produced a piece of work that incited violence and celebrated the most damaging insurrection in American history.

The source material for Birth of a Nation came from two novels, The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden (1902) and The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), both written by Griffith’s Johns Hopkins classmate, Thomas Dixon. Dixon drew on the common-sense version of history he imbibed from his unreconstructed Confederate forebears. According to this master narrative, the Civil War was as a gallant but failed bid for independence, followed by vindictive Yankee occupation and eventual redemption secured with the help of organizations like the Klan.

But Dixon’s fiction, and the subsequent screenplay (by Griffith and Frank E. Woods), was a literal and figurative romance of reconciliation. The movie dramatizes the relationships between two (related) families, the Camerons of South Carolina and the Stonemans of Pennsylvania. The evil patriarch of the latter is Austin Stoneman, a Congressman with a limp very obviously patterned on the real-life Thaddeus Stevens. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Stevens comes, Carpetbagger-style, and uses a brutish black minion, Silas Lynch(!), whose horrifying sexual machinations focused, ironically and naturally, on Stoneman’s own daughter are only arrested by at the last minute, thanks to the arrival of the Klan in a dramatic finale that has lost none of its excitement even in an age of computer-generated imagery.

Historians agree that Griffith, a former actor who directed hundreds of short films in the years preceding Birth of a Nation, was not a cinematic pioneer along the lines of Edwin S. Porter, whose 1903 proto-Western The Great Train Robbery virtually invented modern visual grammar. Instead, Griffith’s genius was three-fold. First, he absorbed and codified a series of techniques, among them close-ups, fadeouts, and long shots, into a distinctive visual signature. Second, he boldly made Birth of a Nation on an unprecedented scale in terms of length, the size of the production, and his ambition to re-create past events (“history with lightning,” in the words of another classmate, Woodrow Wilson, who screened the film at the White House). Finally, in the way the movie was financed, released and promoted, Griffith transformed what had been a disreputable working-class medium and staked its power as a source of genuine artistic achievement. Even now, it’s hard not to be awed by the intensity of Griffith’s recreation of Civil War battles or his re-enactments of events like the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

But Birth of a Nation was a source of instant controversy. Griffith may have thought he was simply projecting common sense, but a broad national audience, some of which had lived through the Civil War, did not necessarily agree. The film’s release also coincided with the beginnings of African American political mobilization. As Melvyn Stokes shows in his elegant 2009 book D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, the film’s promoters and its critics alike found the controversy surrounding it curiously symbiotic, as moviegoers flocked to see what the fuss was about and the fledgling National Association for the Advancement of Colored People used the film’s notoriety to build its membership ranks.

Birth of a Nation never escaped from the original shadows that clouded its reception. Later films like Gone with the Wind (1939), which shared much of its political outlook, nevertheless went to great lengths to sidestep controversy. (The Klan is only alluded to as “a political meeting” rather than depicted the way it was in Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel.) Today Birth is largely an academic curio, typically viewed in settings where its racism looms over any aesthetic or other assessment.

In a number of respects, Steven Spielberg’s new film Lincoln is a repudiation of Griffith. In Birth, Lincoln is a martyr whose gentle approach to his adversaries is tragically severed with his death. But in Lincoln he’s the determined champion of emancipation, willing to prosecute the war fully until freedom is secure. The Stevens character of Lincoln, played by Tommy Lee Jones, is not quite the hero. But his radical abolitionism is at least respected, and the very thing that tarred him in Birth — having a secret black mistress — here becomes a badge of honor. Rarely do the rhythms of history oscillate so sharply. Griffith would no doubt be bemused. But he could take such satisfaction in the way his work has reverberated across time.

For Jim Cullen’s selection of films all history and film buffs should see, watch his video syllabus.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jim Cullen teaches history at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in New York City. He is the author of Sensing the Past: Hollywood Stars and Historical Visions (December 2012), The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation, and other books. Cullen is also a book review editor at the History News Network. Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only TV and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Birth of a Nation film poster, 1915, public domain in Wikimedia Commons.

The post The strange career of Birth of a Nation appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

keilinh,

on 2/6/2013

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

diversity,

black history month,

Book giveaway,

Civil War,

guest blogger,

Janet Halfmann,

African/African American Interest,

Robert Smalls,

Add a tag

Everyone knows Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Jr., but there are many other African Americans who have contributed to the rich fabric of our country but whose names have fallen through the cracks of history.

We’ve asked some of our authors who chose to write biographies of these talented leaders why we should remember them. We’ll feature their answers throughout Black History Month.

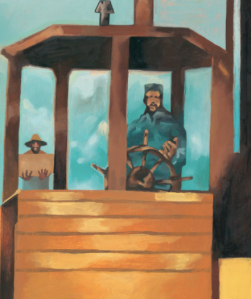

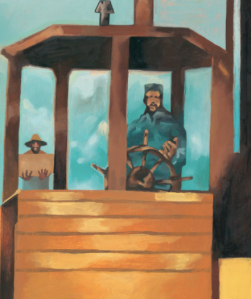

Today, Janet Halfmann shares why she wrote about Robert Smalls in Seven Miles to Freedom:

I was inspired to write about Robert Smalls because he played a very important part in the Civil War, but his role has received little recognition. He showed exceptional bravery, skill, and intelligence in stealing a gunboat from right under the eyes of the Confederates and sailing it through South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor to Union lines. I felt he was a great role model for anyone facing challenges. Also, I was riveted by his heart-thumping escape, and I thought kids would be, too. It was a great adventure story, just waiting to be told.

Robert Smalls and countless other African-Americans played important roles in helping to win the Civil War. In the past, not many of these stories have been included in history books. I feel it’s important for all Americans, and especially for African-American children, that the entire story be told. All children need role models that look like them.

Robert Smalls’ achievements deserve recognition for many reasons. During slavery, many people considered blacks incapable of ever measuring up to whites. Robert Smalls’ bravery and intelligence helped to prove this idea wrong. Robert Smalls was so popular after his escape that Union military officers in South Carolina sent him North to speak and raise money for the many newly freed men, women, and children streaming into Union camps. He also met with President Lincoln and helped to convince him to let African-Americans enlist in the Union army.

After Robert Smalls’ escape to freedom, he had a distinguished career as a civilian ship pilot for the Union. He was the first African-American named a captain of a United States ship. After the war, he helped write a new state constitution, which included his proposal for the creation of South Carolina’s first free system of public schools for all children. He went on to serve five terms in Congress, working for equal rights for all people. Robert Smalls was so popular in his hometown that he was called the “King of Beaufort County.”

Want to win a copy of Seven Miles to Freedom? Enter our Black History Month book giveaway.

Filed under:

guest blogger Tagged:

African/African American Interest,

black history month,

Book giveaway,

Civil War,

diversity,

History,

Janet Halfmann,

Robert Smalls

By: Alice,

on 1/30/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

civil war,

illness,

African American Studies,

suffering,

refugee,

African American History,

emancipation proclamation,

reconstruction,

*Featured,

contraband,

Online Products,

Oxford African American Studies Center,

Oxford AASC,

Tim Allen,

freedmen,

Freedmen's Bureau,

health crisis,

Jim Downs,

Sick from Freedom,

freedpeople,

History,

US,

Add a tag

The editors of the Oxford African American Studies Center spoke to Professor Jim Downs, author of Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, about the legacy of the Emancipation Proclamation 150 years after it was first issued. We discuss the health crisis that affected so many freedpeople after emancipation, current views of the Emancipation Proclamation, and insights into the public health crises of today.

Emancipation was problematic, indeed disastrous, for so many freedpeople, particularly in terms of their health. What was the connection between newfound freedom and health?

I would not say that emancipation was problematic; it was a critical and necessary step in ending slavery. I would first argue that emancipation was not an ending point but part of a protracted process that began with the collapse of slavery. By examining freedpeople’s health conditions, we can see how that process unfolded—we can see how enslaved people liberated themselves from the shackles of Southern plantations but then were confronted with a number of questions: How would they survive? Where would they get their next meal? Where were they to live? How would they survive in a country torn apart by war and disease?

Due to the fact that freedpeople lacked many of these basic necessities, hundreds of thousands of former slaves became sick and died.

The traditional narrative of emancipation begins with liberation from slavery in 1862-63 and follows freedpeople returning to Southern plantations after the war for employment in 1865 and then culminates with grassroots political mobilization that led to the Reconstruction Amendments in the late 1860s. This story places formal politics as the central organizing principle in the destruction of slavery and the movement toward citizenship without considering the realities of freedpeople’s lives during this seven- to eight- year period. By investigating freedpeople’s health conditions, we first notice that many formerly enslaved people died during this period and did not live to see the amendments that granted citizenship and suffrage. They survived slavery but perished during emancipation—a fact that few historians have considered. Additionally, for those that did survive both slavery and emancipation, it was not such a triumphant story; without food, clothing, shelter, and medicine, emancipation unleashed a number of insurmountable challenges for the newly freed.

Was the health crisis that befell freedpeople after emancipation any person, government, or organization’s fault? Was the lack of a sufficient social support system a product of ignorance or, rather, a lack of concern?

The health crises that befell freedpeople after emancipation resulted largely from the mere fact that no one considered how freedpeople would survive the war and emancipation; no one was prepared for the human realities of emancipation. Congress and the President focused on the political question that emancipation raised: what was the status of formerly enslaved people in the Republic?

When the federal government did consider freedpeople’s condition in the final years of the war, they thought the solution was to simply return freedpeople to Southern plantations as laborers. Yet, no one in Washington thought through the process of agricultural production: Where was the fertile land? (Much of it was destroyed during the war; and countless acres were depleted before the war, which was why Southern planters wanted to move west.) How long would crops grow? How would freedpeople survive in the meantime?

Meanwhile, a drought erupted in the immediate aftermath of the war that thwarted even the most earnest attempts to develop a free labor economy in the South. Therefore, as a historian, I am less invested in arguing that someone is at fault, and more committed to understanding the various economic and political forces that led to the outbreak of sickness and suffering. Creating a new economic system in the South required time and planning; it could not be accomplished simply by sending freedpeople back to Southern plantations and farms. And in the interim of this process, which seemed like a good plan by federal leaders in Washington, a different reality unfolded on the ground in the postwar South. Land and labor did not offer an immediate panacea to the war’s destruction, the process of emancipation, and the ultimate rebuilding of the South. Consequently, freedpeople suffered during this period.

When the federal government did establish the Medical Division of the Freedmen’s Bureau – an agency that established over 40 hospitals in the South, employed over 120 physicians, and treated an estimated one million freedpeople — the institution often lacked the finances, personnel, and resources to stop the spread of disease. In sum, the government did not create this division with a humanitarian — or to use 19th century parlance, “benevolence” — mission, but rather designed this institution with the hope of creating a healthy labor force.

So, if an epidemic broke out, the Bureau would do its best to stop its spread. Yet, as soon as the number of patients declined, the Bureau shut down the hospital. The Bureau relied on a system of statistical reporting that dictated the lifespan of a hospital. When a physician reported a declining number of patients treated, admitted, or died in the hospital, Washington officials would order the hospital to be closed. However, the statistical report failed to capture the actual behavior of a virus, like smallpox. Just because the numbers declined in a given period did not mean that the virus stopped spreading among susceptible freedpeople. Often, it continued to infect formerly enslaved people, but because the initial symptoms of smallpox got confused with other illnesses it was overlooked. Or, as was often the case, the Bureau doctor in an isolated region noticed a decline among a handful of patients, but not too far away in a neighboring plantation or town, where the Bureau doctor did not visit, smallpox spread and remained unreported. Yet, according to the documentation at a particular moment the virus seemed to dissipate, which was not the case. So, even when the government, in the shape of Bureau doctors, tried to do its best to halt the spread of the disease, there were not enough doctors stationed throughout the South to monitor the virus, and their methods of reporting on smallpox were problematic.

You draw an interesting distinction between the terms refugee and freedmen as they were applied to emancipated slaves at different times. What did the term refugee entail and how was it a problematic description?

I actually think that freedmen or freedpeople could be a somewhat misleading term, because it defines formerly enslaved people purely in terms of their political status—the term freed places a polish on their condition and glosses over their experience during the war in which the military and federal government defined them as both contraband and refugees. Often forced to live in “contraband camps,” which were makeshift camps that surrounded the perimeter of Union camps, former slaves’ experience resembled a condition more associated with that of refugees. More to the point, the term freed does not seem to jibe with what I uncovered in the records—the Union Army treats formerly enslaved people with contempt, they assign them to laborious work, they feed them scraps, they relegate them to muddy camps where they are lucky if they can use a discarded army tent to protect themselves against the cold and rain. The term freedpeople does not seem applicable to those conditions.

That said, I struggle with my usage of these terms, because on one level they are politically no longer enslaved, but they are not “freed” in the ways in which the prevailing history defines them as politically mobile and autonomous. And then on a simply rhetorical level, freedpeople is a less awkward and clumsy expression than constantly writing formerly enslaved people.

Finally, during the war abolitionists and federal officials argued over these terms and classifications and in the records. During the war years, the Union army referred to the formerly enslaved as refugees, contraband, and even fugitives. When the war ended, the federal government classified formerly enslaved people as freedmen, and used the term refugee to refer to white Southerners displaced by the war. This is fascinating because it implies that white people can be dislocated and strung out but that formerly enslaved people can’t be—and if they are it does not matter, because they are “free.”

Based on your understanding of the historical record, what were Lincoln’s (and the federal government’s) goals in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation? Do you see any differences between these goals and the way in which the Emancipation Proclamation is popularly understood?

The Emancipation Proclamation was a military tactic to deplete the Southern labor force. This was Lincoln’s main goal—it invariably, according to many historians, shifted the focus of the war from a war for the Union to a war of emancipation. I never really understood what that meant, or why there was such a fuss over this distinction, largely because enslaved people had already begun to free themselves before the Emancipation Proclamation and many continued to do so after it without always knowing about the formal proclamation.

The implicit claim historians make when explaining how the motivation for the war shifted seems to imply that the Union soldiers thusly cared about emancipation so that the idea that it was a military tactic fades from view and instead we are placed in a position of imagining Union soldiers entering the Confederacy to destroy slavery—that they were somehow concerned about black people. Yet, what I continue to find in the record is case after case of Union officials making no distinction about the objective of the war and rounding up formerly enslaved people and shuffling them into former slave pens, barricading them in refugee camps, sending them on death marches to regions in need of laborers. I begin to lose my patience when various historians prop up the image of the Union army (or even Lincoln) as great emancipators when on the ground they literally turned their backs on children who starved to death; children who froze to death; children whose bodies were covered with smallpox. So, from where I stand, I see the Emancipation Proclamation as a central, important, and critical document that served a valuable purpose, but the sources quickly divert my attention to the suffering and sickness that defined freedpeople’s experience on the ground.

Do you see any parallels between the situation of post-Civil War freedpeople and the plights of currently distressed populations in the United States and abroad? What can we learn about public health crises, marginalized groups, etc.?

Yes, I do, but I would prefer to put this discussion on hold momentarily and simply say that we can see parallels today, right now. For example, there is a massive outbreak of the flu spreading across the country. Some are even referring to it as an epidemic. Yet in Harlem, New York, the pharmacies are currently operating with a policy that they cannot administer flu shots to children under the age of 17, which means that if a mother took time off from work and made it to Rite Aid, she can’t get her children their necessary shots. Given that all pharmacies in that region follow a particular policy, she and her children are stuck. In Connecticut, Kathy Lee Gifford of NBC’s Today Show relayed a similar problem, but she explained that she continued to travel throughout the state until she could find a pharmacy to administer her husband a flu shot. The mother in Harlem, who relies on the bus or subway, has to wait until Rite Aid revises its policy. Rite Aid is revising the policy now, as I write this response, but this means that everyday that it takes for a well-intentioned, well-meaning pharmacy to amend its rules, the mother in Harlem or mother in any other impoverished area must continue to send her children to school without the flu shot, where they remain susceptible to the virus.

In the Civil War records, I saw a similar health crisis unfold: people were not dying from complicated, unknown illnesses but rather from the failures of a bureaucracy, from the inability to provide basic medical relief to those in need, and from the fact that their economic status greatly determined their access to basic health care.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Jim Downs on the Emancipation Proclamation appeared first on OUPblog.

I know some of you may find this hard to believe, but here goes. It’s not that easy to get middle-schoolers interested in history. It’s so . . . yesterday.

I know some of you may find this hard to believe, but here goes. It’s not that easy to get middle-schoolers interested in history. It’s so . . . yesterday.

And then authors like Margo L. Dill come along with finely-researched and gripping historical fiction like Finding My Place: One Girl's Strength at Vicksburg and teachers can breathe a happy sigh of relief.

But you don’t have to be a teacher to sigh happily over Finding My Place. There’s plenty for everyone to like in Dill’s authentic and plucky thirteen-year-old protagonist, Anna Green, and her riveting story about the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg. In Anna’s Civil War tale, we’re grabbed from the first page and taken on a journey beyond the battlefields where Rebels and Blue Bellies fight. Anna brings readers to the emotional heart of life during the War Between the States.

Finding My Place literally starts with a bang. Grant’s army is desperate to take the advantageously-situated city of Vicksburg, and so the local citizens have retreated to caves built in the surrounding soft clay hills to escape constant shelling. We feel Anna’s anguish as she, along with her mother and siblings, rush to take cover and wait to see what their future will be. We learn that Anna fears for the safety of her older brother and father, who are fighting in General Lee’s army.

And then unbearable tragedy strikes, and Anna is forced to somehow find a way to keep her hurting family together, all the while trying to find her own place in this new and harrowing world that used to be home.

I so love this young heroine, Anna. She’s courageous, yes, but she struggles with her fears and the deprivations of siege conditions in the way that any thirteen-year-old would. She’s challenged by constant doubts, and yet she finds the determination to do what needs to be done. Anna’s voice carries the story with adolescent honesty, whether she’s describing the horrors of a Civil War hospital, the possibility of eating rats, the inhumane treatment of a neighbor’s slave, or the awakening of feelings she has for a certain handsome young man.

I’m a big fan of historical fiction. I love finding gems of information, the fascinating tidbits left out of the history books. And I especially like when a well-crafted, believable story brings history alive for me. Margo L. Dill has done a great job of providing both in her debut novel, Finding My Place.

Educational resources are included, making this novel an excellent addition to the classroom library as well as the home library. It’s an adventurous read with true-to-life characters and compelling Civil War history that middle-schoolers, boys or girls, will enjoy. And P.S. Even the rather mature way-beyond-middle-schoolers who love history can learn something new in Finding My Place!

*****BOOK GIVEAWAY*****

If

Margo L. Dill sounds familiar that's because she's contributing editor of WOW

! Women On Writing, as well as a columnist, blogger, and instructor. We're so excited about her debut novel, and she graciously provided a copy for giveaway! Enter the Rafflecopter form below for a chance to win.

Finding My Place: One Girl's Strength at Vicksburg makes a great gift for middle-schoolers this holiday season. The contest closes December 6th. If you don't win, you can pick up a copy at

Amazon or an autographed copy on her

website.

Good luck!a Rafflecopter giveaway

Recommended for ages 12 and up.

Laurie Halse Anderson once wrote in her blog that she preferred to call her historical books "historical thrillers" rather than "historical fiction," given that many kids and teens associate historical fiction with BORING. However, it's not every historical fiction title that can be justly called a "thriller." With

A Soldier's Secret, Marissa Moss definitely joins the club of historical thriller writers for teens. Based on the true story of Civil War hero Sarah Edmonds, who enlisted in the Union Army as Frank Thompson, this is one story so full of incredible twists and turns that readers will be compelled have to finish it just to find out what happens.

In this novel, Moss returns to explore in greater depth Sarah Edmonds' life, which she portrayed in the lively 2011 picture book biography

Nurse, Soldier, Spy. When we meet Sarah at the opening of this novel, it's the spring of 1861, and she has been living as Frank Thompson, a traveling book salesman, for more than three years. Writing in the first person, Sarah fills the reader in on her back story growing up on a farm in New Brunswick, Canada, with a cruel and abusive father; when her father is about to force her into an unwanted marriage, Sarah cuts her hair, dresses as a boy, and runs away, ending up in the United States.

But when the war breaks out, the teenaged Sarah wants to be a part of history, and enlists in the Union Army as Private Frank Thompson, Army nurse. An accomplished shot and rider, she is especially skilled at hiding her female parts when she "does her business," and no one questions her sex or her ability as a soldier. Moss does an excellent job portraying the tedium and occasional terror of a soldier's existence through Sarah's eyes, as she wonders if she will be able to measure up in battle. When the Union loses the first Battle of Bull Run, Sarah/Frank no longer needs to wonder; she's running around helping the doctors amputate limbs, writing letters to loved ones, and carrying out the last wishes of dying soldiers, as the reader gets a close-up view of the primitive nature of medical care in the 19th century.

But of course Sarah is a woman, and living in close proximity with so many eligible young men, the inevitable happens--she develops romantic feelings for a fellow soldier, fantasizing about him. Eventually her feelings are so strong, she asks for a reassignment, next serving as a postmaster delivering letters to the troops. Soon she is recruited as a Union spy, where her skill at disguises comes in very handy. She even "disguises" herself as a woman for one of her assignments!

While there are hundreds of documented cases of women disguising themselves as men to fight in the Civil War, Sarah was the only woman to be recognized by Congress as an honorably discharged soldier, with rights to back pay and pension, and the only woman allowed to join the association for Civil War veterans. At her death she was granted a military funeral and buried in a cemetery for Civil War veterans.

Moss' well-researched novel is based in part on Sarah Edmonds' own memoir, as well as many other sources on women in the Civil War and the Civil War in general. Moss includes extensive back matter, including background on Sarah Edmonds, brief biographies of Union Army officers, a brief Civil War timeline, which includes annotations for battles in which Frank/Sarah participated, and selected bibliography.

This is a terrific novel for middle schoolers or high schoolers, male or female. It offers great action, suspense, twists, and star-crossed romance that should intrigue even reluctant readers of historical fiction.

By: Alice,

on 9/4/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Current Affairs,

World War II,

Lincoln,

civil war,

Barack Obama,

Vietnam,

gulf war,

George Bush,

fdr,

Nixon,

kissinger,

osama bin laden,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Mark Owen,

American Presidency at War,

Andrew Polsky,

Elusive Victories,

Navy SEALs,

No Easy Day,

Add a tag

By Andrew J. Polsky

No Easy Day, the new book by a member of the SEAL team that killed Osama bin Laden on 30 April 2011, has attracted widespread comment, most of it focused on whether bin Laden posed a threat at the time he was gunned down. Another theme in the account by Mark Owen (a pseudonym) is how the team members openly weighed the political ramifications of their actions. As the Huffington Post reports:

Though he praises the president for green-lighting the risky assault, Owen says the SEALS joked that Obama would take credit for their success…. one SEAL joked, “And we’ll get Obama reelected for sure. I can see him now, talking about how he killed bin Laden.”

Owen goes on to comment that he and his peers understood that they were “tools in the toolbox, and when things go well [political leaders] promote it.” It is an observation that invites only one response: Duh.

Of course, a president will bask in the glow of a national security success. The more interesting question, though, is whether it translates into gains for him and/or his party in the next election. The direct political impact of a military victory, a peace agreement, or (as in this case) the elimination of a high-profile adversary tends to be short-lived. That said, events may not be isolated; they also figure in the narratives politicians and parties tell. For Barack Obama and the Democrats in 2012, this secondary effect is the more important one.

Wartime presidents have always been sensitive to the ticking of the political clock. In the summer of 1864, Abraham Lincoln famously fretted that he would lose his reelection bid. Grant’s army stalled at Petersburg after staggering casualties in his Overland campaign; Sherman’s army seemed just as frustrated in the siege of Atlanta; and a small Confederate army led by Jubal Early advanced through the Shenandoah Valley to the very outskirts of Washington. So bleak were the president’s political fortunes that Republicans spoke openly of holding a second convention to choose a different nominee. Only the string of Union victories — at Atlanta, in the Shenandoah Valley, and at Mobile Bay — before the election turned the political tide.

Election timing may tempt a president to shape national security decisions for political advantage. In the Second World War, Franklin Roosevelt was eager to see US troops invade North Africa before November 1942. Partly he was motivated by a desire to see American forces engage the German army to forestall popular demands to redirect resources to the war against Japan, the more hated enemy. But Roosevelt also wanted a major American offensive before the mid-term elections to deflect attention from wartime shortages and labor disputes that fed Republican attacks on his party’s management of the war effort. To his credit, he didn’t insist on a specific pre-election date for Operation Torch, and the invasion finally came a week after the voters had gone to the polls (and inflicted significant losses on his party).

The Vietnam War illustrates the intimate tie between what happens on the battlefield and elections back home. In the wake of the Tet Offensive in early 1968, Lyndon Johnson came within a whisker of losing the New Hampshire Democratic primary, an outcome widely interpreted as a defeat. He soon announced his withdrawal from the presidential race. Four years later, on the eve of the 1972 election, Richard Nixon delivered the ultimate “October surprise”: Secretary of State Henry Kissinger announced that “peace is at hand,” following conclusion of a preliminary agreement with Hanoi’s lead negotiator Le Duc Tho. In fact, however, Kissinger left out a key detail. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu balked at the terms and refused to sign. Only after weeks of pressure, threats, and secret promises from Nixon, plus renewed heavy bombing of Hanoi, did Thieu grudgingly accept a new agreement that didn’t differ in its significant provisions from the October version.

But national security success yields ephemeral political gains. After the smashing coalition triumph in the 1991 Gulf War, George H. W. Bush enjoyed strikingly high public approval ratings. Indeed, he was so popular that a number of leading Democrats concluded he was unbeatable and decided not to seek their party’s presidential nomination the following year. But by fall 1992 the victory glow had worn off, and the public focused instead on domestic matters, especially a sluggish economy. Bill Clinton’s notable ability to project empathy played much better than Bush’s detachment.

And so it has been with Osama and Obama. Following the former’s death, the president received the expected bump in the polls. Predictably, though, the gain didn’t persist amid disappointing economic results and showdowns with Congress over the debt ceiling. From the poll results, we might conclude that Owen and his Seal buddies were mistaken about the political impact of their operation.

But there is more to it. Republicans have long enjoyed a political edge on national security, but not this year. The death of Osama bin Laden, coupled with a limited military intervention in Libya that brought down an unpopular dictator and ongoing drone attacks against suspected terrorist groups, has inoculated Barack Obama from charges of being soft on America’s enemies. Add the end of the Iraq War and the gradual withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan and the narrative takes shape: here is a president who understands how to use force efficiently and with minimal risk to American lives. Thus far Mitt Romney’s efforts to sound “tougher” on foreign policy have fallen flat with the voters. That he so rarely brings up national security issues demonstrates how little traction his message has.

None of this guarantees that the president will win a second term. The election, like the one in 1992, will be much more about the economy. But the Seal team operation reminds us that war and politics are never separated.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

This colouring/activity page is for you to print out and give to children - yours, someone else's or to use in a school or library. Not to be used for commercial purposes.

Simply click on the image and print.

Don't forget to follow my blog so you will receive the latest Kid's Page.

Toodles!

Hazel

Release date: June 19, 2012

Are your tweens and teens clamoring to see the soon-to-be-released Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter movie, opening on June 22? If you're hoping they'll be interested in learning something about this great American, beyond what's offered in the hilariously satirical novel on which the movie is based, you could do worse than to steer them to a new book on Lincoln and the great African-American hero Frederick Douglass by Russell Freedman.

Russell Freedman is one of our best nonfiction writers for young people; an earlier biography he published on Abraham Lincoln won the Newbery award many years ago. Anyone with an interest in American history will be sure to enjoy his newest book, which comes out on June 19. It's a joint biography of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The book opens with Douglass waiting to see Lincoln in the White House in 1863, the only black man in a waiting area crowded with people waiting to see the president. Freedman then presents the life of stories of these two great men in alternating chapters. Toward the end of the book, their stories merge as the Civil War breaks out. They only met on a few occasions, but they had much in common, and shared a common purpose--ridding the United States of slavery. The book is abundantly illustrated with photographs, drawings, and paintings, and includes a selected bibliography, notes, and picture credits. At just over 100 pages, it's a relatively quick read, and an excellent introduction to the lives of both of these important icons in American history.

Highly recommended for ages 10 and up.

By: shelf-employed,

on 6/4/2012

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

history,

book review,

nonfiction,

slavery,

Civil War,

Non-Fiction Monday,

Abraham Lincoln,

Frederick Douglass,

Advance Reader Copy,

Add a tag

Freedman, Russell. 2012.

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The date is August 10, 1863. Frederick Douglass has arrived at the White House, taking a seat on the stairs, determined to speak with President Lincoln. Many others are waiting as well. Douglass stands out in the crowd, not just for his size. All the other petitioners are White. Douglass, a freed Black is an outspoken critic of Lincoln. The two men have never met. Douglass has no appointment. He is prepared to wait.

He does not wait long, however. The President

does see Frederick Douglass on August 10, 1863; and in

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship, award-winning author, Russell Freedman tells us why.

Freedman is a master writer, and ingeniously sets up this story of friendship. Chapter One, "Waiting for Mr. Lincoln," sets the stage. The next three chapters detail the life of Frederick Douglass before his meeting with Lincoln. Three subsequent chapters do the same for the President. The final three chapters highlight the collaboration of the two men in pursuit of their mutual interest, abolition.

The extensive use of period photographs and artwork, as well as images of period realia (election poster, paycheck, editorial cartoons and the like) add interest to an already compelling story. The depth of Lincoln's regard for Douglass is cemented by the revelation that Mary Todd Lincoln sent Douglass a memento after Lincoln's death, knowing that Lincoln had "wanted to do something to express his warm personal regard" for Douglass.

Appendix:

Dialogue Between a Master and Slave, Historic Sites, Selected Bibliography, Notes (on the sources of more than one hundred quotes) and Picture Credits (including many from the Newbery Medal-winning Russell Freedman book,

Lincoln: A Photobiography) round out this extensively researched book.

The Contents page indicates an Index beginning on page 115, however, it was apparently not completed in time for the printing of the Advance Reading Copies.

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglas is suggested for Grades 4-7, and is due on shelves June 19, 2012. It is a fascinating look at two of the most influential men of their time by one of the great children's authors of our time. Highly recommended.

Recently I shopped at Barnes and Nobles. Browsing through the children's area I came across several great historical books. Behind Rebel Lines is the first book I've read and am reviewing from this shopping trip. Soon I'll be reviewing other history books on westward expansion, traveling in a covered wagon, Colonial America, and the Titanic.

It has been nearly 100 years since the sinking of the Titanic. I noticed at Barnes and Nobles they have several choices in books for young readers. I may make a trip back to browse more from this subject.

Sarah Emma Edmonds had left Canada at a young age and relocated to Michigan where she worked as a farm hand. She was physically hardy, independent, brave, bold. When the Civil War began she enlisted in the Union Army as a man, her new identity was Franklin Thompson. Thankfully she was able to work as a nurse, which meant she was able to have more privacy in her living quarters, "instead of a crowded company tent.".

Later she interviewed for and got a job as a spy. Several times she crossed Rebel enemy lines disguised as a black slave man or woman. She also disguised herself as an Irish peddler woman. She made 11 spying missions for the Union. She was apparently a talented actor and master disguiser.

I loved reading this book! It is a story I'd not heard before. I learned that there were over 400 women during the Civil War that disguised themselves as men in order to fight in the war.

Emma Edmonds was a gutsy woman. She certainly had no qualms about rebelling against society and culture standards for her day. She made a decisive and brave choice to fight for her country.

Her personality was such that she was not an impulsive dreamy person. She was instead intelligent, perceptive, wise.

For more information about Sarah Emma Edmonds:

http://www.civilwarhome.com/edmondsbio.htmhttp://www.thekentuckycivilwarbugle.com/2011-4Qpages/emmaedmonds.htmlhttp://susanna-mcleod.suite101.com/canadian-sarah-emma-edmonds-a-civil-war-spy-a186190 Published by

Harcourt August 1, 2001

Young Adult Non-Fiction/Civil War/Spy/Biography

144 pages

This book to me would be for ages 9 and up.

I bought my copy at the Barnes and Nobles store:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/behind-rebel-lines-seymour-v-reit/1100467739Paperback $6.25

Link @ Barnes and Nobles for more Great Episode Books:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?series_id=155109Link @ Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/Behind-Rebel-Lines-Incredible-Episodes/dp/0152004246Paperback $6.95

Blissful Reading!

Annette

Our house has a fairly large wrap-around porch and Alison and I love to use it whenever we can. We watched New Year's Eve fireworks from it this year and have used it in the past to view parades and bicycle and foot races. But just sitting in a wicker chair as the night wears along is a peaceful joy. Traffic dies down at 11 PM and the world becomes very still and deep. When leaves are present, when they surround and embrace the porch, very little light -- whether from street or porch lights or the moon -- disrupts the dark shadows. It becomes a refuge, a haven to escape the day-to-day pressures and responsibilities, a place where I often find myself thinking of the past.*

*

Sitting there I sometimes wonder if the original owners of our house sat out at night as we do? The house was built in 1905 and our town of Maplewood was just beginning to grow and change, with new streets being carved through old apple orchards, sturdy wood frame houses slowly rising up. What did those first owners hear at night? The lonely clip-clop of horse's hooves? The huff and chug of the steam train from Newark? And when did the first automobile make its way past the house? *

*

And what about other owners through the years? What was it like to sit in the absolute quiet of a dark night when the world wars were raging? Did someone bring a radio out to listen to the latest reports from Europe or the Pacific? Did anyone sit on the porch during a heavy snow fall (as I often do) to be surrounded by cold and white and gusting winds? Or stay out when a summer thunderstorm came rumbling through? Yes, I have been known to experience all sorts of storms out there.*

*

And, of course, there are those strange, sometimes unsettling moments, especially after midnight. Twenty years ago we often heard the distant voice of a young girl calling plaintively in the night: "Mommy... Mommy... Mommy..." We nicknamed her the Ghost Child and dispite going out to make sure everything was okay and despite asking neighbors, it was years before we found out the truth. It was indeed a young girl and she was searching for a loved one -- her cat, which escaped regularly and was named Monty!*

*

That was a disappointing end to the story. We had hoped for something a little more, shall we say, picturesque. But the Ghost Child has been replaced these days by the Night Rider. Late at night, usually after midnight, we can hear the thrum of a skateboarder making his or her way up Maplewood Avenue toward our house. The sound gets louder and louder until they get to the corner that borders our house where the rider turns and pushes hard to sail up the side street. We have never actually seen the rider, it's that dark. Just a quick glimpse of moving shadow and then the sound of the wheels fades away into the night. Who is the Night Rider? Where did they come from and where are they going? Will they be safe?*

*

These are decidedly small bits of history. Incidents really that usually aren't recorded because they're, well, so every day and common. But I believe that much interesting history begins with the ordinary. Take what happened to Corporal Barton Mitchell and his friend on September 13, 1862. When the 27th Indiana Infantry halted their march just outside of Frederick, Maryland, Mitchell and his pal went over to rest in the shade and happened to spot a rolled-up piece of paper in the tall grass. It turned out to be Special Order No. 191 (where Robert E. Lee divided up his army). If these two soldiers hadn't found the paper and hadn't realized it was important, there would have been no Battle of Antietam, Lee would have probably been able to reunite his forces, and that would have meant a far different battle between Lee and McClellan than Antietam (and who knows when or even if the Emancipation Proclamation would have been issued!).*

*

Finding those orders was pure dumb luck, but it resulted in an historic battle that changed the course of the war and the world. A tiny bit of history, a mere moment really, that had profound e

Recommended for 14 and up.

In a vague way, most of us have heard of John Brown and his famous raid on Harper's Ferry that preceded the Civil War. Best-selling nonfiction author Horwitz points out that the event merits a mere six paragraphs in his son's 9th grade history textbook. In this compelling new work, Horwitz examines not only John Brown's own history and background but the forces in society that led to his carefully plotted conspiracy.

A descendant of the Puritans, Brown was a committed abolitionist who was not afraid to use violence to help overthrow slavery in the United States. He and his many sons participated in the pre-Civil War fighting between abolitionists and pro-slavery forces in Kansas, before spearheading the formation of a private army. His ultimate aim--no less than seizing the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, and freeing all the slaves. How this conspiracy developed and its high profile aftermath is the subject of Horwitz' riveting new work.

Through contemporary eyes, Horwitz notes, we are tempted to see John Brown as an al-Queda type of terrorist, a "long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U.S. government...in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power." In this book, Horwitz paints a much more complex picture of a charismatic leader of a large family, a man who mixed with prominent industrialists who supported him financially as well as intellectuals such as Frederick Douglass and Henry David Thoreau. He examines John Brown's early life and the events which led to his taking up arms against his own country.

Although the insurrection was quickly put down by future Civil War leader Robert E. Lee, the case mesmerized the nation, polarizing North and South, abolitionists and those who supported slavery. He became a hero to many in the North and a traitor to those in the South. Horwitz remarks "Harpers Ferry wasn't simply a prelude to secession and civil war. In many respects, it was a dress rehearsal. "

|

| John Brown |

I have been a fan of Horwitz since reading his earlier book

Confederates in the Attic, in

which he tries to understand Americans' ongoing obsession with all things Civil War. Unlike many of his earlier works, which merge personal narrative with historical passages, this book about John Brown is more of a traditional narrative non-fiction history work. Horwitz' elegant prose reads like a novel, and this book offers an in-depth and fascinating portrait of one of history's pivotal characters, and an important epoch in American history. While this is an adult title, I would highly recommend it to high school students with a strong interest in history as well.

Authors site and for more information on this incredible story:

http://judieoron.com/http://youtu.be/lAlUc2UxP0ILink for the book @ Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/Cry-Giraffe-Judie-Oron/dp/1554512727Hardback $16.48

Paperback $10.36

Link for the book @ publisher:

http://site.annickpress.com/catalog/catalog.aspx?Title=Cry+of+the+Giraffe - 2011 USBBY Outstanding International Books Honor List

- 2011 Sydney Taylor Notable Book for Teens

- White Ravens Collection, International Youth Library, Munich

- 2011 Helen and Stan Vine Canadian Jewish Book Award

- Amelia Bloomer Project 2011 List, ALA

- YALSA Hidden Gems

Cry of the Giraffe is on Facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Cry-of-the-Giraffe/152399418116528?sk=wallPublished by

Annick Press July 2010

208 pages/Non-fiction/Grades 8 and up

Slavery/Ethiopian Jew/Refugee/Abuse/War

Once again I've read a story I'd not heard of before. The true story of Jewish refugees fleeing the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple that traveled and settled in Ethiopia. These Jewish Ethiopians lived in their own communities for a long time, waiting until they could settle back in the land of their father's. They called themselves Beta Israel or House of Israel. When Israel became a statehood in 1948 they waited patiently for the ability to resettle there. In the 1980's Ethiopia became ever more hostile to them and they began fleeing to Sudan to await a hopeful flight out of Sudan and to Israel. While waiting in these refugee camps in Sudan the abuse, neglect, starvation, and disease was horrifying and rampant. Families were torn apart literally, some never seeing each other again. Others were parted for long periods of time. More than 4,000 would die.

There are120,000 Ethiopian Jews living in Israel now.

Cry of the Giraffe is the story of Wuditu a young girl living in a village in Ethiopia with her brother Dawid and mother. Their mother was the first wife of their father Berihun. He had a second wife and several daughters with her. Each of the wives lived with their own children in separate houses.

This family early in the book began to leave Ethiopia walking with a guide all the way to Sudan. After reaching there the

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

Abraham Lincoln is a source of endless fascination to Americans of all ages; more books have been written about him than any other figure in American history. This new biography for young people by Lincoln expert Harold Holzer is a worthwhile addition to the pantheon of Lincoln books, and could be enjoyed by young people and adults alike.

The outlines of Lincoln's life are well known to most of us; this volume concentrates on Lincoln's personality as a father, the lives of his four sons, and what happened to the two sons that survived him and to their descendants, a story that most people are less familiar with.

Although Lincoln was famous for his wit and love of telling jokes, his private life was as imbued with personal sadness as his presidency was full of grief and sorrow for most U.S. citizens, a huge percentage of whom lost family members during the Civil War. Holzer chooses to begin his story with the death of Abraham Lincoln II, known as Jack--Lincoln's only grandson. Like three of Lincoln's own sons, Jack died tragically at a young age, succumbing to blood poisoning at the young age of sixteen.

|

| Lincoln with his son Tad |

Holzer then turns his attention to the Lincolns who came before Jack, as the authors puts it, "the story of the clan that might have become America's royal family but instead became America's cursed family--and then disappeared altogether." We learn about Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln's courtship, their early married life (in which they initially lived in one room in a boarding house--quite a shock for Mary Todd who came from a wealthy family). Their first son, Robert, was followed a few years later by Eddie, who was a sickly child and died shortly before his fourth birthday. Death of children was common in the 19th century; nonetheless, his parents were devastated. Lincoln cried openly, and Mary was in such despair that Abraham was forced to remind her, "Eat, Mary, for we must live." Although they never got over his loss, Mary was soon pregnant again, giving birth to Willie and then to Thomas, quickly nicknamed Tad, when his father remarked he looked like a baby frog, or tadpole.

The book is full of colorful anecdotes about the Lincoln boys and their family life, including for example, excerpts of a charming letter little Willie wrote to a friend while on a trip with his father to Chicago in 1859. We also learn about their schooling; Robert Lincoln failed his first exams to get into Harvard, and Tad had such difficulty sitting still and learning to read that today he would probably have been diagnosed with learning disabilities. The Lincolns were incredibly indulgent parents, especially for their day, when children were expected to be "seen and not heard,"

By: Lauren,

on 5/16/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

national mall,

*Featured,

disunion,

Art & Architecture,

Images & Slideshows,

charles lockwood,

district of columbia,

john lockwood,

Pennsylvania Avenue,

siege of washington,

washington dc history,

willard’s,

New York Times,

US,

civil war,

sesquicentennial,

washington,

Washington D.C.,

white house,

capitol,

Add a tag

By John Lockwood and Charles Lockwood

The Washington of April 1861—also commonly known as “Washington City”—was a compact town. Due to the cost of draining marshy land and the lack of reliable omnibus service, development was focused around Pennsylvania Avenue between the Capitol and White House. When the equestrian statue of George Washington was dedicated at Washington Circle in 1860, its location—three-quarters of a mile west of the White House, where Twenty-Third Street intersects Pennsylvania Avenue—was described as out of town. Several blocks north of the White House, at L Street, the land was countryside. “Go there, and you will find yourself not only out of town, away among the fields,” wrote English novelist Anthony Trollope in his travel account, North America, after his 1861 visit, “but you will find yourself beyond the fields, in an uncultivated, undrained wilderness.” A writer for the Atlantic Monthly, writing in January 1861, deemed Washington a “paradise of paradoxes,” foremost because it was both “populous” and “uninhabited” at once. Noting another paradox, he observed that the capital was ‘[d]efenceless, as regards walls, redoubts, moats, or other fortifications”—though the only party to “lay siege” to the city of late were the unyielding onslaught of politicians and office seekers, not soldiers.

Travelers arriving from northern cities caught a glimpse of the city’s grandeur and squalor as their train pulled into the B & O Station at the foot of Capitol Hill. “I looked out and saw a vast mass of white marble towering above us on the left . . . surmounted by an unfinished cupola, from which scaffold and cranes raised their black arms. This was the Capitol,” wrote Times of London correspondent William Russell, who arrived in Washington at the end of March 1861. “To the right was a cleared space of mud, sand, and fields, studded with wooden sheds and huts, beyond which, again, could be seen rudimentary streets of small red brick houses, and some church-spires above them.”

From the B & O Station, most carriages and hacks headed westward down Pennsylvania Avenue, the city’s main artery. The Avenue was the traditional route for grand parades between the Capitol and the White House, and by the mid-nineteenth-century, its north side was the location for the city’s finest hotels and shops. Yet many visitors, particularly those from leading cities like New York or London, were unimpressed by its pretensions to grandeur, and found the cityscape a formless jumble. Pennsylvania Avenue, observed Russell, was “a street of much breadth and length, lined with ailanthus trees . . . and by the most irregularly-built houses [and commercial buildings] in all kinds of materials, from deal plank to marble—of all heights.”

At the corner of Fourteenth Street, one block before Pennsylvania Avenue made its northward turn at the Treasury before continuing west past the White House, stood Willard’s Hotel. The hotel, favored by Republican Party leaders, was the center of Washington’s social and business life under the new administration. Willard’s contained “more scheming, plotting, planning heads, m

Recommended for ages 8-12. This second offering in

Laurie Calkhoven's Boys of Wartime series for middle-grade readers tells the compelling story of 12-year old Will, who lives in the quiet town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and dreams of glory as a Union drummer boy. He's too young to enlist without his parents' permission, which his mother is not about to give, but when the book opens Will has no idea of the important role he'll be asked to play for the Union cause.

As Confederate troops march into the town, prowling the streets "like hungry wolves," even forcing the local candy story owner to open his shop so they can clear out the goodies, Will makes an unexpected friend--a drummer boy his age from Tennessee, a friendship that will soon prove more valuable than he can imagine. Will is as surprised as can be when he finds himself inviting the hungry and dirty boy to supper, where he is greeted with courtesy by Will's family (his mother even offers the ragged boy clean clothes). Through Will's eyes, we see how the battle came about, with the two sides meeting pretty much by chance at the crossroads of ten major roads at Gettysburg, making a battle at a town the commanders of both armies had never heard of all but inevitable.

As the battle draws near town, Will's sisters are taken to a neighbor's farm nearby, where his mother thinks they will be out of the way of the battle. As Confederate soldiers take the town on July 1, Will meets an injured Union officer who is desperate to get a message to General Meade. Can Will help him get through the Confederate lines to complete his mission? Should he join up with the Union officer and become his messenger?

This is an exciting war novel for middle grade students; as a civilian, Will's character offers a different perspective on the war than we find in many children's novels. First he's excited to see all the soldiers, and dreams of enlisting himself. Soon, however, he experiences the horrible sights, sounds, and even smells of battle as he discovers that the peaceful farm where his sisters had been sent has been converted to a hospital, crammed with injured and dying men moaning in pain, begging for water, and filled with the noise of the surgeon sawing off ruined limbs. He finds himself on the battle's front lines in spite of himself, as the battle progresses to different locations around the town. Calkhoven vividly describes the sights and sounds of the battlefield--the cannon fire shaking the earth, the roaring of the guns--making us feel that we are right beside young Will. She also gives us a good perspective on what is happening in the town, where Union soldiers are hiding in Will's mother's house, which is searched by Confederates who Will's mother winds up cooking dinner for. His house, too, fills up with wounded soldiers.

Calkhoven concludes her novel with Will hearing Lincoln's very short--but later very famous--address at the dedication of the cemetery for the thousands of dead soldiers at Gettysburg. Will even has a chance to shake the famous man's hand.

The novel includes an historical note, brief biographical information on real historic characters who appear in the novel, a timeline of the battle of Gettysburg and the Civil War, and a glossary.

Recommended for ages 8-12.

Beloved author-illustrator

Patricia Polacco returns to the Civil War in her newest picture book aimed at older readers. This story, suitable for upper-elementary school-aged children, follows two brothers, Michael and Derek, who visit the Harpers Ferry Civil War Museum with their grandmother. Initially annoyed when their grandmother tells them that on this trip there will be "no music, no texting, no tweeting, no e-mailing," they decide that the Civil War was "way cool" when they see the guns and cannons in the museum. Soon they have a chance to slip into some Union uniforms, and they're told by the eccentric museum director that when they step through a door, they'll find themselves in Antietam just after the battle. It's a game, he tells them, and they're not allowed to tell anyone they're from 2011. Also, they have to make sure to come back before sunset.

But when they pass through the door, they're ordered to help photographer Matthew Brady and his assistant, Gardner, who are there to photograph the battlefield and the President's meeting with General McClellan. The boys can't help but wonder where on earth the game found an actor that looks so much like President Lincoln. When the boys look with shock at all the dead bodies, they realize this is no game, and soon they are comforting President Lincoln himself, who is agonizing over all the death and destruction he sees. Derek can't help himself--he tells Lincoln that the North will win, and that one day, a black man will be president! Derek and Michael must rush to get back to the present, where their grandmother insists that they have participated in a reenactment, where groups act out important battles of the war. But when the boys examine the photo of Lincoln and McClellan in the museum--they find a surprise that might validate their trip back in time.

|

| contemporary cartoon of Lincoln |

Patricia Polacco knows how to tell an engrossing story, and kids will certainly enjoy this time-travel story about two ordinary boys who wind up meeting President Lincoln and seeing one of the most devastating battles of the Civil War (Antietam was the single bloodiest day in the war, with almost 23,000 casualties). Her signature style artwork, done in pencils and markers, of the battle scenes is particularly powerful (you can see many of the 2-page spreads from the book on

Polacco's website), although the cover image of Lincoln brought to my mind how during his lifetime Lincoln was often called in his own day an ape, baboon or gorilla. Somehow in Polacco's cover artwork Lincoln has more than a little bit of a chimp look about him, don't you think?

The book includes a brief bibliography and an author's note, in which Polacco gives additional details about the history of Antietam that ar

By: Lauren,

on 4/20/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Biography,

US,

civil war,

kentucky,

sesquicentennial,

gettysburg,

fever,

Research Tools,

civil war history,

blackburn,

American National Biography,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Mark C. Carnes

General Editor, ANB

The 150th anniversary of the Civil War will be commemorated in the usual ways. But a truly unique approach is provided by the online—and thus searchable—version of the American National Biography, a 27-million word collection of biographical essays on some 18,731 deceased Americans who played a significant role in the nation’s past.

Readers can of course acquire an understanding of the major figures, perhaps beginning with James M. McPherson’s long essays on Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant and Russell F. Weigley’s on Robert E. Lee. But there are many hundreds of essays on figures associated with all aspects of the war.

Those interested in a particular battle, for instance, can use the ANB online. A full-text search of articles for “Gettysburg” yields 253 separate biographical essays, the great majority on soldiers who fought there.

But this search also unearths many new gems of information, such as the fact that William Corby, a Roman Catholic priest assigned to New York’s Irish Brigade, stood upon a boulder, raised his right hand, and offered a general absolution for the combatants just before the armies converged.

Women, too, surface in this search. Eliza Farnham, the author of Life in Prairie Land (1846) and a crusader for prison reform and women’s causes, tended the wounded at Gettysburg, where she contracted tuberculosis; she died the next year at age 49. Eliza Turner, an early feminist, abolitionist, and poet, also cared for the wounded at Gettysburg. She later wrote an important woman suffrage tract. Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave who became the dressmaker, dresser, and confidante of Mary Lincoln, attended the Gettysburg commemoration with the first lady.