new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: oxford english dictionary, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 56

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: oxford english dictionary in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 12/16/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Boxing Day,

new year's day,

christmas day,

bank holiday,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

oxford dictionaries,

james murray,

oxfordwords,

Beverley Hunt,

baksheesh,

heslop,

pillion,

corf,

holidays,

christmas,

Dictionaries,

bank,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

boxing,

Add a tag

By Beverley Hunt

With just over a week to go until Christmas, many of us are no doubt looking forward to the holidays and a few days off work. For those working on the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, however, writing the history of the language sometimes took precedence over a Christmas break.

Christmas leave in the UK today centres around a number of bank holidays, so called because they are days when, traditionally, banks closed for business. Before 1834, the Bank of England recognized about 33 religious festivals but this was reduced to just four in 1834 – Good Friday, 1 May, 1 November, and Christmas Day. It was the Bank Holidays Act of 1871 that saw bank holidays officially introduced for the first time. These designated four holidays in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland — Easter Monday, Whit Monday, the first Monday in August, and Boxing Day. Good Friday and Christmas Day were seen as traditional days of rest so did not need to be included in the Act. Scotland was granted five days of holiday — New Year’s Day, Good Friday, the first Monday in May, the first Monday in August, and Christmas Day.

So when James Murray took over as editor of the OED in 1879, Christmas Day was an accepted holiday across the whole of the UK, Boxing Day a bank holiday everywhere except Scotland, and New Year’s Day a bank holiday only in Scotland. Yet this didn’t stop editors and contributors toiling away on dictionary work on all three of those dates.

At Christmas play and make good cheer

Here is the first page of a lengthy letter to James Murray from fellow philologist Walter Skeat, written on Christmas Day, 1905. Skeat does at least start his letter with some seasonal greetings and sign off “in haste”, but talks at length about the word pillion in between! There are at least two other letters in the OED archives written on Christmas Day – a letter from W. Boyd-Dawkins in 1883 about the word aphanozygous (apparently the cheekbones being invisible when the skull is viewed from above, who knew?), and another from R.C.A. Prior about croquet in 1892.

Boxing clever

Written on Boxing Day, 1891, this letter to James Murray is from Richard Oliver Heslop, author of Northumberland Words. After an exchange of festive pleasantries, Oliver Heslop writes about the word corb as a possible misuse for the basket known as a corf, clearly a pressing issue whilst eating turkey leftovers! Many other Boxing Day letters reside in the OED archives, amongst them a 1932 letter to OUP’s Kenneth Sisam from editor William Craigie concerning potential honours in the New Year Honours list following completion of the supplement to the OED.

Out with the old, in with the new

Speaking of New Year, here is a “useless” letter to James Murray from OUP’s Printer Horace Hart, written on New Year’s Day, 1886. Although not an official holiday in Oxford at that time, this letter provides a nice opportunity for discussing the etymology of the term Boxing Day. The first weekday after Christmas Day became known as Boxing Day as it was the day when postmen, errand-boys, and servants of various kinds expected to receive a Christmas box as a monetary reward for their services during the previous year. This letter talks about baksheesh, a word used in parts of Asia for a gratuity or tip.

Holidays are coming

In case you’re wondering, New Year’s Day was granted as an additional bank holiday in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland in 1974, as was Boxing Day in Scotland (and 2 January from 1973). So the whole of the UK now gets all three as official days of leave in which to enjoy the festive season.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Beverley Hunt is Archivist for the Oxford English Dictionary but will not be archiving on Christmas Day, Boxing Day, or New Year’s Day.

If you’re feeling inspired by the words featured in today’s blog post, why not take some time to explore OED Online? Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number. If you are in the US, why not give the gift of language to a loved-one this holiday season? We’re offering a 20% discount on all new gift subscriptions to the OED to all customers residing in the Americas.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OxfordWords blog via RSS.

The post Don’t bank on it appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlanaP,

on 12/5/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

richard holden,

elon,

musk,

Geography,

words,

Dictionaries,

mars,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

place of the year,

martians,

Atlas of the World,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Add a tag

By Richard Holden

The planet Mars might initially seem an odd choice for Place of the Year. It has hardly any atmosphere and is more or less geologically inactive, meaning that it has remained essentially unchanged for millions of years. 2012 isn’t much different from one million BC as far as Mars is concerned.

However, here on Earth, 2012 has been a notable year for the red planet. Although no human has (yet?) visited Mars, our robot representatives have, and for the last year or so the Curiosity rover has been beaming back intimate photographs of the planet (and itself). (It’s also been narrating its adventures on Twitter.) As a result of this, Mars has perhaps become less of an object and more of a place (one that can be explored on Google Maps, albeit without the Street View facility).

Our changing relationship with Mars over time is shown in the development of its related words. Although modern readers will probably associate the word ‘Mars’ most readily with the planet (or perhaps the chocolate bar, if your primary concerns are more earthbound), the planet itself takes its name from Mars, the Roman god of war.

Drawing of Mars from the 1810 text, “The pantheon: or Ancient history of the gods of Greece and Rome. Intended to facilitate the understanding of the classical authors, and of poets in general. For the use of schools, and young persons of both sexes” by Edward Baldwin, Esq. Image courtesy the New York Public Library.

From the name of this god we also get the word martial (relating to fighting or war), and the name of the month of March, which occurs at a time of a year at which many festivals in honour of Mars were held, probably because spring represented the beginning of the military campaign season.

Of course, nobody believes in the Roman gods anymore, so confusion between the planet and deity is limited. In the time of the Romans, the planet Mars was nothing more than a bright point in the sky (albeit one that took a curious wandering path in comparison to the fixed stars). But as observing technology improved over centuries, and Mars’s status as our nearest neighbour in the solar system became clear, speculation on its potential residents increased.

This is shown clearly in the history of the word martian. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the most common early usage of the word was as an adjective in the sense ‘of or relating to war’. (Although the very earliest use found, from Chaucer in c1395, is in a different sense to this — relating to the supposed astrological influence of the planet.)

But in the late 19th century, as observations of the surface of the planet increased in resolution, the idea of an present of formed intelligent civilization on Mars took hold, and another sense of martian came into use, denoting its (real or imagined) inhabitants. These were thought by some to be responsible for the ‘canals’ that they discerned on Mars’s surface (these later proved to be nothing more than an optical illusion). As well as (more or less) scientific speculation, Martians also became a mainstay of science fiction, the earth-invaders of H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898) being probably the most famous example.

A century on, robotic explorers such as the Viking probes and the aforementioned Curiosity have shown Mars to be an inhospitable, arid place, unlikely to harbour any advanced alien societies. Instead, our best hope for the existence of any real Martians is in the form of microbes, evidence for which Curiosity may yet uncover.

If no such evidence of life is found, perhaps the real Martians will be future human settlers. Despite the success of Martian exploration using robots proxies, the idea of humans visiting or settling Mars is still a romantic and tempting one, despite the many difficulties this would involve. Just this year, it was reported that Elon Musk, one of the co-founders of PayPal, wishes to establish a colony of 80,000 people on the planet.

The Greek equivalent of the Roman god Mars is Ares; as such, the prefix areo- is sometimes used to form words relating to the planet. Perhaps, then, if travel to Mars becomes a reality, we’ll begin to talk about the brave areonauts making this tough and unforgiving journey.

Richard Holden is an editor of science words for the Oxford English Dictionary, and an online editor for Oxford Dictionaries.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language. It is an unsurpassed guide to the meaning, history, and pronunciation of 600,000 words — past and present — from across the English-speaking world. Most UK public libraries offer free access to OED Online from your home computer using just your library card number. If you are in the US, why not give the gift of language to a loved-one this holiday season? We’re offering a 20% discount on all new gift subscriptions to the OED to all customers residing in the Americas.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mars: A lexicographer’s perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/24/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

cowboy,

Dictionaries,

caribbean,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

word origin,

bailey,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

buckaroo,

Efik,

vaquero,

Katrin Thier,

‘cowboy’,

katrin,

thier,

Add a tag

We (unintentionally) started a debate about the origin of the word “buckaroo” with our quiz Can you speak American? last week. Richard Bailey, author of Speaking American, argues that it comes from the West African language Efik. Here OED editor Dr. Katrin Thier argues that the origin isn’t quite so clear.

By Dr. Katrin Thier

The origin of the word buckaroo is difficult to establish and is still a matter of debate. In the sense ‘cowboy’ it first appears in the early 19th century, written bakhara in the earliest source currently known to us, but used alongside other words of clearly Spanish origin. Later variants include baccaro, buccahro, and buckhara. On the face of it, a derivation from Spanish vaquero ‘cowboy’ looks likely, especially as the initial sound of the Spanish word is essentially the same as b- in English. The stress of the English word was apparently originally on the second syllable, as in Spanish, and only shifted to the final syllable later.

However, there is evidence from the Caribbean for a number of very similar and much earlier forms, such as bacchararo (1684), bockorau (1737), and backaroes (1740, plural), used by people of African descent to denote white people. This word then spreads from the Caribbean islands to the south of the North American continent. From the end of the 18th century, it is often contracted and now usually appears as buckra or backra, but trisyllablic forms such as buckera still occur in the 19th century. This word was brought from Africa and derives from the trisyllabic Efik word mbakára ‘white man, European’. Efik is a (non-Bantu) Niger-Congo language spoken around Calabar, a former slave port in what is now southern Nigeria.

Given the multi-ethnic and multilingual make-up of the south of the United States, it seems conceivable that similar words of different origin could meet and interact, influencing each other to generate new forms and meanings. However, a number of difficulties remain in explaining the change of sense and also the varying stress pattern if the word of Efik origin is assumed to be the sole origin of buckaroo ‘cowboy’.

This is a word that we look forward very much to researching in detail for the new edition of the Oxford English Dictionary currently in progress. We would welcome any earlier examples of the word in the meaning ‘cowboy’, if any readers know of any.

Dr. Katrin Thier is Senior Etymology Editor at the Oxford English Dictionary.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/18/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

word histories,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

concise oed,

concise oxford english dictionary,

Reference,

language,

words,

Dictionaries,

fowler,

english,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

new words,

Add a tag

By Angus Stevenson

Since the publication of its first edition in 1911, the revolutionary Concise Oxford Dictionary has remained in print and gained fame around the world over the course of eleven editions. This month heralds the publication of the centenary edition: the new 12th edition of the Concise Oxford English Dictionary contains some 400 new entries, including cyberbullying, domestic goddess, gastric band, sexting, slow food, and textspeak.

By: Michelle,

on 5/23/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

slideshow,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

Will Shortz,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Audio & Podcasts,

Caleb Madison,

crosswords,

JASA,

caleb,

sundays,

impressively,

podcast,

Reference,

wordplay,

crossword,

Dictionaries,

puzzle,

oxford english dictionary,

Leisure,

Add a tag

Want more of The Oxford Comment? Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes.

You can also look back at past episodes on the archive page.

Featured in this Episode:

Michelle goes on-site with former Oxford intern Caleb Madison, the youngest person to publish a crossword puzzle in the New York Times (at the age of 15). A puzzle by his class at Sundays at JASA: A Program of Sunday Activities for Older Adults was recently published in the New York Times and featured on the Wordplay blog.

Lauren gets a private tour of the OED museum in Oxford with Archivist Martin Maw.

This slideshow features the crossword class in action, and some impressively old printing relics.

(Click the image if you would like to see it larger.)

-

Rock bands

lightbox

-

Rock stars

lightbox

-

How would you clue that?

lightbox

-

The roof, the roof

lightbox

-

Catching up after class

lightbox

-

Caleb Madison with

lightbox

-

his student Carmel Kuperman

lightbox

By: Lauren,

on 4/6/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

alcohol,

liquor,

word origins,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Food & Drink,

anatoly liberman,

booze,

word history,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

james murray,

history of booze,

bouse,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Booze is an enigmatic word, but not the way ale, beer and mead are. Those emerged centuries ago, and it does not come as a surprise that we have doubts about their ultimate origin. The noun booze is different: it does not seem to predate the beginning or the 18th century, with the verb booze “to tipple, guzzle” making its way into a written text as early as 1300 (which means that it turned up in everyday speech some time earlier). The riddles connected with booze are two.

First, why did the noun appear so much later than the verb? A parallel case will elucidate the problem. The verb meet is ancient, while the noun meet is recent, and we can immediately see the reason for the delay: sports journalists needed a word for a “meeting” of athletes and teams and coined a meet, whose popularity infuriated some lovers of English, but, once the purists died out, the word became commonplace (this is how language changes: if a novelty succeeds in surviving its critics, it stays and makes the impression of having been around forever). But the noun booze is not a technical term and should not have waited four hundred years before it joined the vocabulary. Second, the verb booze is a doublet of bouse (it rhymes with carouse, which is fair). Strangely, bouse has all but disappeared, and booze (sorry for a miserable pun) is on everybody’s lips. However, it is not so much the death of bouse that should bother us as the difference in vowels. The vowel we have in cow or round was once “long u” (as in today’s coo). Therefore, bouse has the pronunciation one expects, whereas booze looks Middle English. In the northern dialects of English “long u” did not become a diphthong, and this is probably why uncouth still rhymes with youth instead of south. Is booze a northern doublet of bouse? One can sense Murray’s frustration with this hypothesis. He wrote: “Perhaps really a dialectal form” (and cited a similar Scots word). It is the most uncharacteristic insertion of really that gives away Murray’s dismay. His style, while composing entries, was business-like and crisp; contrary to most people around us, he preferred not to strew his explanations with really, actually, definitely, certainly, and other fluffy adverbs: he was a scholar, not a preacher.

Whatever the causes of the modern pronunciation of booze, one etymology will cover both it and bouse. So what is the origin of bouse? This word is surrounded by numerous nouns and verbs, some of which must be and others may be related to it. First of all, its Dutch and German synonyms buizen and bausen spring to mind. Both are rare to the extent of not being known to most native speakers, but their use in the past has been recorded beyond any doubt. Most other words refer to swelling, violent or erratic movement, and noise: for instance, Dutch buisen “strike, knock” and, on the other hand, beuzelen “dawdle, trifle,” Norwegian baus “arrogant; irascible” and bause “put on airs” (which partly explains the sense of Dutch boos and Germa

By: Anastasia Goodstein,

on 3/25/2011

Blog:

Ypulse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

harpercollins,

facebook,

youtube,

oxford english dictionary,

Ypulse Essentials,

Simon & Schuster,

imbee,

lady gaga,

everloop,

NFFTY,

rebecca black,

In the Book Loop,

Lady Gaga goes country,

Multiracial Youth,

Add a tag

The Oxford English Dictionary (♥s shorthand. The online edition now contains text message and IM lingo like LOL, BFF and the heart symbol. Surprisingly these words date back beyond today’s teens; OMG first appeared in 1917! But does putting... Read the rest of this post

The Oxford English Dictionary (♥s shorthand. The online edition now contains text message and IM lingo like LOL, BFF and the heart symbol. Surprisingly these words date back beyond today’s teens; OMG first appeared in 1917! But does putting... Read the rest of this post

By: Lauren,

on 3/25/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Poetry,

Videos,

Video,

interactive,

Disney,

Dictionaries,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

friday,

Leisure,

george michael,

smithsonian,

subway,

linked up,

*Featured,

rebecca black,

interactive timeline,

morning news,

saxaphone,

gizfactory,

losteyeball,

bostinnovation,

viddler,

etyman,

oxfordwords,

Add a tag

Dearest readers,

I think this might be the best collection of links I’ve ever gathered. So, you’re welcome. Have a wonderful weekend!

Next Stop Atlantic: a photo series documenting the hurling of MTA subway cars into the Atlantic Ocean to create artificial reefs for sea creatures. [My Modern Met]

“He doesn’t like George Michael! Boo!” This saxaphone player is committed. (I dare you not to laugh.) [Viddler]

There’s a reason you didn’t get an A+ on your creative writing homework. (Dare you not to laugh at this one, either.) [losteyeball]

Your head could look like a book. [Gizfactory]

Have you been reading The Morning News’s ‘Lunch Poems‘ series? [The Morning News]

The Word Guy gets PENsive. [Etyman]

Path of Protest: an interactive timeline of recent Middle East events [Guardian]

Nick Pitera does it again: a one-man Disney soundtrack. [YouTube]

Hilarious, ‘hardcore’, but fake Smithsonian ads [BostInnovation]

I know everyone has probably heard enough about ‘Friday’/Rebecca Black, but I have to offer up this if-you-laugh-you-lose challenge. [Johnny]

And finally, the award for Tweet of the Week goes to the Oxford Dictionaries team. [OxfordWords]

By: Lauren,

on 3/25/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Dictionaries,

tgif,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

frigg,

friday,

word history,

Research Tools,

case of the mondays,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

rebecca black,

friday look,

ˈfraɪˌdeɪ,

Add a tag

By Lauren Appelwick, Blog Editor

Yesterday I was sitting at my desk, pondering…normal things that bloggers ponder…when my friend Cassie shared this link with me. If you haven’t seen the “Friday” music video, then perhaps the forecast just seems silly, but it inspired me to think about how fast the senses and connotations of words change. For most people, Friday is just the name of a day of the week, but for the moment it’s also the source of many inside jokes and references to Rebecca Black. She is, obviously, a big fan of Fridays because it marks the end of her school week and the beginning of the weekend. We have such acronyms to show our love for the day as TGIF (Thank God It’s Friday), and what seems to be a widespread distaste for Mondays. (*Ahem* Garfield. *Cough* Office Space.)

So the question is: did people always like Friday? Did we choose Friday as the end of the work week because it was already well-loved?

{ASIDE: I was just beginning my research when fellow blogger Levi Asher (Literary Kicks) teased me with this Wikipedia link, encouraging that I “meet [his] friend Frigg.” To this I replied, “How long have you been friends?” and he answered, “Since Thor’s Day.” Well played, Levi. Well played indeed.}

We begin with the OED.

Friday, n.

Pronunciation: Brit. /ˈfrʌɪdeɪ/ , /ˈfrʌɪdi/ , U.S. /ˈfraɪˌdeɪ/ , /ˈfraɪdi/

1. The day following Thursday and preceding Saturday, traditionally regarded as the sixth day of the week, but now frequently considered as the fifth, and also as the last day of the working week and (especially in the evening) the start of the weekend. In the Catholic Church, Friday, along with Wednesday and Saturday, has traditionally been observed as one of the days for abstaining from eating meat, fish being the popular alternative. In Judaism, sunset on Friday marks the beginning of the Sabbath, which ends at sunset on Saturday.

So far, pretty simple. We see that Friday’s position in the week is appears to be most strongly connected to Judeo-Christian traditions. I didn’t really expect to discover anything spectacular, I was just satiating my own curiosity–and why bother the Oxford Etymologist with such small queries? But then I noticed a sense that was new to me.

Friday-look, n.

now rare (Eng. regional in later use). a serious or gloomy face or expression (cf.

0 Comments on A short (and incomplete) history of Friday as of 1/1/1900

By Michelle Rafferty

Last week we prepared for the Academy Awards by discussing words and phrases coined from film (twitterpated, to bogart, party on) as well as linguistic choices in film this year (Winkelvii, ballerina lingo, The Kids are All Right, not alright) . While watching the awards last night it occurred to me that we failed to address one of the most important cinematic words of all time: dude. Or in the parlance of our time: The Dude.

But before we get to Lebowski (who, thanks to Sandra Bullock, did get a shout-out last night) let’s go back 30 years, when Hollywood gave us surfer dude. According to Matt Kohl, Senior Editorial Researcher at the OED:

The negative stigma resulted from earlier Hollywood portrayals of surf culture, which were by and large unflattering, especially with respect to intelligence. Spicoli in Fast Times (1982) is a pretty iconic example.

And then:

15+ years later, we get Lebowski from the Coen brothers. Though there are some indications of Spicoli in him: long hair, shabby attire, and a relaxed attitude toward drug-use and the law, it’s evident right away that The Dude isn’t derivative of Fast Times, Bill & Ted, or any other 80s dude convention…For the generation of viewers that fell in love with The Big Lebowski, dude took on a whole new meaning.

"Duuuude" vs. The Dude

While the Cohen brothers’ dude continues to have positive associations, religious adherence in some cases (see: dudeism, Lebowski Fest), the surfer sense of dude has seen substantial backlash in the last 5-10 years. As Matt told me:

Now some surfers won’t use the word at all. In fact, there’s a making-of feature in Riding Giants, which is one of the more high-profile surf movies to come out recently, in which the director talks about the fact that none of the surfers featured in his movie uses “dude” or any of that beach-stoner vernacular.

Where Dude Originally Came From

Oscar Wilde, the original dude?

When the term first

By Dennis Baron

There’s a federal law that defines writing. Because the meaning of the words in our laws isn’t always clear, the very first of our federal laws, the Dictionary Act–the name for Title 1, Chapter 1, Section 1, of the U.S. Code–defines what some of the words in the rest of the Code mean, both to guide legal interpretation and to eliminate the need to explain those words each time they appear. Writing is one of the words it defines, but the definition needs an upgrade.

The Dictionary Act consists of a single sentence, an introduction and ten short clauses defining a minute subset of our legal vocabulary, words like person, officer, signature, oath, and last but not least, writing. This is necessary because sometimes a word’s legal meaning differs from its ordinary meaning. But changes in writing technology have rendered the Act’s definition of writing seriously out of date.

The Dictionary Act tells us that in the law, singular includes plural and plural, singular, unless context says otherwise; the present tense includes the future; and the masculine includes the feminine (but not the other way around–so much for equal protection).

The Act specifies that signature includes “a mark when the person making the same intended it as such,” and that oath includes affirmation. Apparently there’s a lot of insanity in the law, because the Dictionary Act finds it necessary to specify that “the words ‘insane’ and ‘insane person’ and ‘lunatic’ shall include every idiot, lunatic, insane person, and person non compos mentis.”

The Dictionary Act also tells us that “persons are corporations . . . as well as individuals,” which is why AT&T is currently trying to convince the Supreme Court that it is a person entitled to “personal privacy.” (The Act doesn’t specify whether “insane person” includes “insane corporation.”)

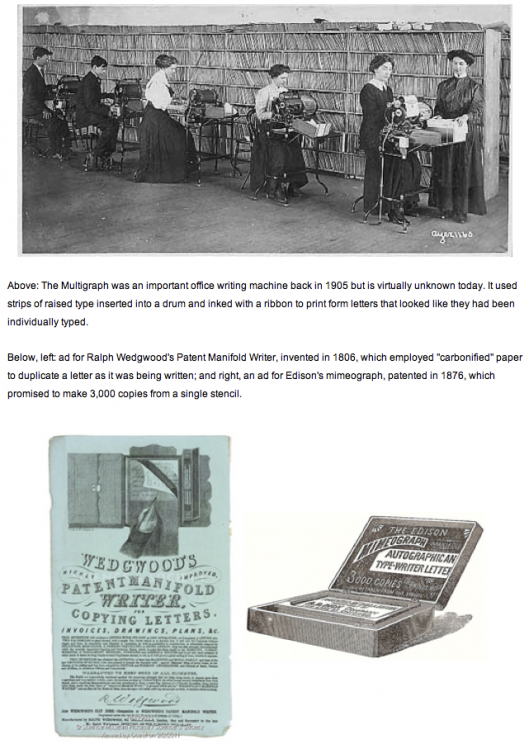

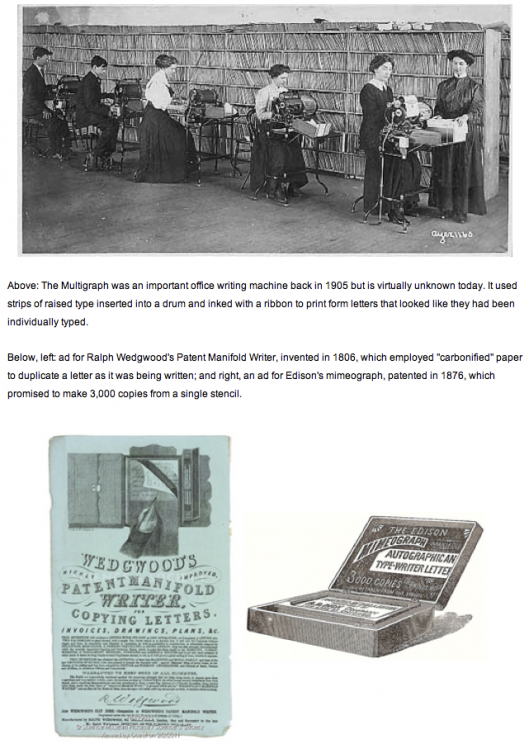

And then there’s the definition of writing. The final provision of the Act defines writing to include “printing and typewriting and reproductions of visual symbols by photographing, multigraphing, mimeographing, manifolding, or otherwise.” There’s no mention of Braille, for example, or of photocopying, or of computers and mobile phones, which seem now to be the primary means of transmitting text, though presumably they and Facebook and Twitter and all the writing technologies that have yet to appear are covered by the law’s blanket phrase “or otherwise.”

Federal law can’t be expected to keep up with every writing technology that comes along, but the newest of the six kinds of writing that the Dictionary Act does refer to–the multigraph–was invented around 1900 and has long since disappeared. No one has ever heard of multigraphing, or of manifolding, an even older and deader technology, and for most of us the mimeograph is at best a dim memory.

Congress considers writing important enough to the nation’s well-being to include it in the Dictionary Act, but not important enough to bring up to date, and now, with the 2012 election looming, no member of Congress is likely to support a revision to the current definition that is semantically accurate yet co

With the Academy Awards right around the corner, we thought it might be fun to look at the lexical impact of films and some words that were actually coined by movies. Joining us for this Quickcast are two “excellent” members of the esteemed Oxford English Dictionary team.

Want more of The Oxford Comment? Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

You can also look back at past episodes on the archive page.

Featured in this Episode:

Katherine Connor Martin, Senior Editor – OED

Matt Kohl, Senior Editorial Researcher – OED

And should you be interested in getting a hippopotamus for Christmas…

* * *

Lights, camera, lexicon: the language of films in the OED

By Katherine Connor Martin

Film, that great popular art form of the twentieth century, is a valuable window on the evolving English language, as well as a catalyst of its evolution. Film scripts form an important element of the OED’s reading programme, and the number of citations from films in the revised OED multiplies with each quarterly update. The earliest film cited in the revised OED, The Headless Horseman (1922), actually dates from the silent era (the quotation is taken from the text of the titles which explain the on-screen action), but most quotations from film scripts represent spoken English, and as such provide crucial evidence for colloquial and slang usages which are under-represented in print.

Scripts as sources

It is therefore no surprise that, although the films cited in OED represent a wide range of genres and topics, movies about teenagers are especially prominent. The film most frequently cited thus far in the OED revision, with 11 quotations, is American Graffiti, George Lucas’s 1972 reminiscence of coming of age in the early 1960s; second place is a tie between Heathers (1988), the classic black comedy of American high school, and Purely Belter (2000), a British film about teenagers trying to scrape together the money to buy season tickets for Newcastle United FC. But the impact of cinema on English is not limited simply to providing lexicographical evidence for established usages. From the mid-twentieth century, the movies as mass culture have actually shaped our language, adding new words to the lexicon and propelling subcultural usages into the mainstream.

The use of a word in a single film script can be enough to spark an addition to the lexicon. Take for instance shagadelic, adj., the absurd expression of approval used by Mike Myers in Austin Powers (1997), which has gained a currency independent of that film se

By: Michelle,

on 2/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Battlestar Galactica,

Dictionaries,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

shibboleth,

kara thrace,

fuck,

matt,

katherine,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

frak,

Katherine Connor Martin,

Matt Kohl,

battlestar,

“shibboleth,

sect,

Add a tag

By Michelle Rafferty

127 years ago today the Oxford English Dictionary published its first volume (A to ANT), so I thought I’d pay tribute with the story of how I recently learned the word “shibboleth”:

While rubbing elbows with fancy people at the recent OED re-launch party, I had the chance to meet contributors Matt Kohl and Katherine Connor Martin. Naturally the topic of conversation came to words, and I brought up one I had been using a lot lately: frak (the fictional version of “fuck” on Battlestar Galactica). I explained that I just started watching the show (better late than never, no?) and had been testing “frak” out in conversation to pick up other fans. Matt said, oh that’s a “shibboleth.”

A whateth? According to the OED:

The Hebrew word used by Jephthah as a test-word by which to distinguish the fleeing Ephraimites (who could not pronounce the sh) from his own men the Gileadites (Judges xii. 4–6).

Matt told me that he had first heard the word on The West Wing. Martin Sheen sums it up nicely: a password. A more recent sense in the OED defines shibboleth as:

A catchword or formula adopted by a party or sect, by which their adherents or followers may be discerned, or those not their followers may be excluded.

The sect, in my case, is Battlestar enthusiasts. I e-mailed Katherine later for more examples. She said:

I think politics affords some good examples. The pro-life movement is distinguishable by its use of certain buzz-words (abortionist, abortion-doctor, etc.), and the pro-choice movement by terms like “anti-choice”. Republicans use the word “democrat” as an adjective, while Democrats use the adjective “democratic”. If you ever hear someone talk about the “Democrat Party” on cable TV, you can be sure s/he is a conservative.

Shibboleth, it’s frakking everywhere!

(Thank you to Matt and Katherine for your countless hours spent keeping the OED alive, and for helping me realize the educational value of my addiction.)

"Let's get he frak outta here!" -Kara Thrace, S4E7

It was a lively week fueled largely by misinformation as talk about the Oxford University Press filled blogs and flooded news columns across the Web. “The king’s book may never be seen in print again,” they cried. “Did you hear about those words that were added? What could the king be thinking to allow the lowly words of mere peasants into the holy grail of dictionaries?” For anyone who thought that Dick Snary was companion only to writers and other word-geeks this hoopla was surely a wake-up call. What was the underlying reason for the ruckus? If a book is not available in print do we fear we are being denied the information? If words we consider crass are acknowledged and accepted by a credible source does that somehow dilute the “purity” of our language?

The English language has an almost limitless ability to expand and develop. This is good news for those of us who want to continue to communicate the never-ending evolution of thoughts and ideas. Our ability to express is limited only by our own imagination--or sometimes by our editor—not by printed decree of the king. This is a language created by the people; the use of which can be neither denied nor muffled. It can, however, be recorded.

This brings us back to Oxford University Press and some necessary clarifications:

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) has not yet been printed. The ODE just revised RH--rococoesque and added the section to their draft for the new edition. A couple hundred words were added, mostly in this category, and there were some changes made in sub-categories. The new edition will probably be finished around the year 2020. Retail cost for a published volume set is estimated at $995. No final decision has been made regarding the cessation of printed volumes. The

OED is accessible online for a fee. Why pay for access to an online dictionary when you can look up a word for free? The OED is a historical dictionary as opposed to a current-use dictionary; it is more like an encyclopedic language reference.

It is the new edition the

Oxford Dictionary of English (ODE) which was just released along with its cousin, The

New Oxford American Dictionary. These works are where the 2000 new words appear including Muggle, staycation, paywall and unfriend. The ODE and the NOAD are compilations of the common usage of words.

Dictionaries reflect of our ever changing culture. They provide a window into the social habits and communications of our neighbors and a historical reference for generations to come. Consider all the many forms available to us today. We have dictionaries of medieval words, slang dictionaries in almost every language, and urban dictionaries in which everyday people post new phrases daily. Instead of worrying about what words are added to them let us celebrate what they represent-- our passion for words.

By: Anastasia Goodstein,

on 8/30/2010

Blog:

Ypulse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

facebook,

oxford english dictionary,

jimmy fallon,

Alloy,

glee,

caru,

Ypulse Essentials,

Kmart,

betty white,

emmys,

Toy Story 3,

shopkick,

Add a tag

Jimmy Fallon, 'Glee' and Betty White (made for an "energetically hilarious" start to last night's Emmys. As for the rest of the show? Critics at USA Today and the New York Times, reg. required, gave the former SNL star mixed reviews. Plus... Read the rest of this post

Jimmy Fallon, 'Glee' and Betty White (made for an "energetically hilarious" start to last night's Emmys. As for the rest of the show? Critics at USA Today and the New York Times, reg. required, gave the former SNL star mixed reviews. Plus... Read the rest of this post

By: Lauren,

on 7/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

palin,

Sarah Palin,

word of the year,

Sean Hannity,

urban dictionary,

google books,

hypermiling,

ground zero,

NAACP,

tea-party,

#shakespalin,

language log,

refudiate,

mediaite,

hannity,

Reference,

shakespeare,

Blogs,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

oxford english dictionary,

twitter,

tweet,

Add a tag

Here at Oxford, we love words. We love when they have ancient histories, we love when they have double-meanings, we love when they appear in alphabet soup, and we love when they are made up.

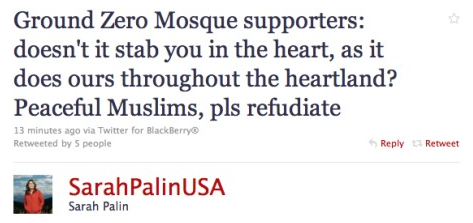

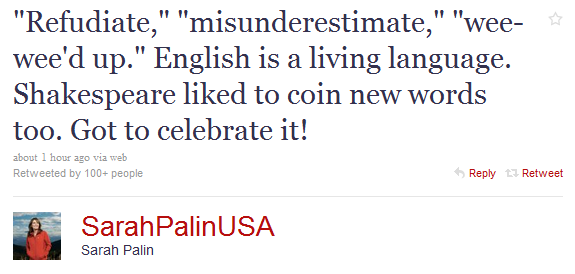

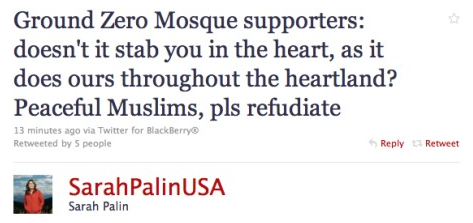

Last week on The Sean Hannity Show, Sarah Palin pushed for the Barack and Michelle Obama to refudiate the NAACP’s claim that the Tea Party movement harbors “racist elements.” (You can still watch the clip on Mediaite and further commentary at CNN.) Refudiate is not a recognized word in the English language, but a curious mix of repudiate and refute. But rather than shrug off the verbal faux pas and take more care in the future, Palin used it again in a tweet this past Sunday.

Note: This tweet has been since deleted and replaced by this one.

Later in the day, Palin responded to the backlash from bloggers and fellow Twitter users with this:

Whether Palin’s word blend was a subconscious stroke of genius, or just a slip of the tongue, it seems to have made a critic out of everyone. (See: #ShakesPalin) Lexicographers sure aren’t staying silent. Peter Sokolowksi of Merriam-Webster wonders, “What shall we call this? The Palin-drome?” And OUP lexicographer Christine Lindberg comments thus:

The err-sat political illuminary Sarah Palin is a notional treasure. And so adornable, too. I wish you liberals would wake up and smell the mooseburgers. Refudiate this, word snobs! Not only do I understand Ms. Palin’s message to our great land, I overstand it. Let us not be countermindful of the paths of freedom stricken by our Founding Fathers, lest we forget the midnight ride of Sam Revere through the streets of Philadelphia, shouting “The British our coming!” Thank the God above that a true patriot voice lives on today in Sarah Palin, who endares to live by the immorternal words of Nathan Henry, “I regret that I have but one language to mangle for my country.”

Mark Liberman over at Language Log asks, “If she really thought that refudiate was Shakespearean, wouldn’t she have left the original tweet proudly in place?”

He also points out that Palin did not coin the refudiate word blend. In fact, he says, “A

By: Lana,

on 2/24/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

oxford english dictionary,

etymology,

thesaurus,

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary,

Buzzword,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Add a tag

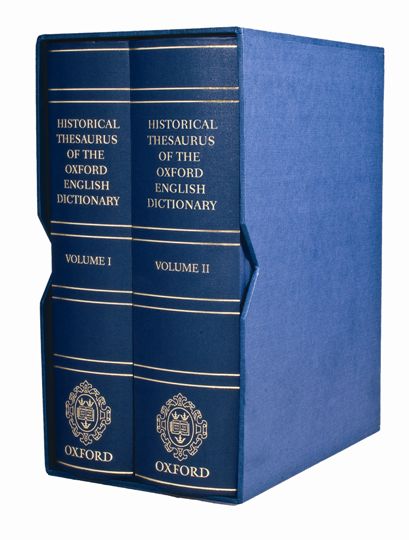

By Anatoly Liberman

Neologists, thesauruses, and etymology. A month ago, one of our correspondents asked what we call people who coin new words. I suggested that such wordsmiths or wordmen may be called neologists. My spellchecker did not like this idea and offered geologist or enologist for neologist, but I did not listen to its advice. Geologists study rocks, and (o)enologists are experts in wine making. Mountains and alcohol are for the young; I have enough trouble keeping my identity among entomologists (the motif of an insect will turn up again at the end of this post). Soon after my answer was posted, a letter came from Marc Alexander, a colleague teaching in Glasgow. He was a member of the team that produced the great Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (this is only part of the title) that Oxford University Press brought out in 2009. He kindly looked up the relevant category in the thesaurus and found the following: logodaedalus (current between 1641 and 1690), logodaedalist (it lived in books between 1721-1806), neologist (which surfaced in 1785 and is still alive), neoterist, and verbarian, coined in 1785 and 1873 respectively, all in all a nice gallery of stillborn freaks. Mr. Alexander adds: “Based on OED citations, neologist is, I think, exclusively one who uses rather one who coins [new words].”

I would like to profit by this opportunity and thank all our readers who comment on my posts (I wish there were more of them) and in addition say something about the role of thesauruses for etymology. When the first volumes of the OED, at that time called NED (New English Dictionary) reached the public, two attitudes clashed, and the polemic was carried out with the acerbity typical of such exchanges in the 18th and the 19th century. (Those who have never read newspapers and popular and semi-popular magazines published in Addison’s days and much later have no idea how virulent their style often was. Both James A.H. Murray and Walter W. Skeat represented the trend in an exemplary way and never missed the chance of calling their opponents benighted, ludicrously uninformed, and unworthy of even the shortest rejoinder; then a long diatribe would usually follow.) Some people praised Murray for including all the words that occurred in printed sources, while others objected to filling the pages of the great national dictionary with obstructive rubbish: they would never have allowed logodaedalist and its likes to mar the pages of a serious reference book. No convincing arguments for or against either position exist. The public will not notice the presence of logodaedalist or use this preposterous word, but those who are interested in the sources of human creativity, for whom language history is not only a list of survivors (be it sounds, forms, syntactic constructions, or words) but a chronicle of battles won and lost will be perennially grateful to the OED for documenting even the words that lived briefly. Such words show how English-speakers have tried to master their language for more than a millennium, and the picture is inspiring from beginning to end.

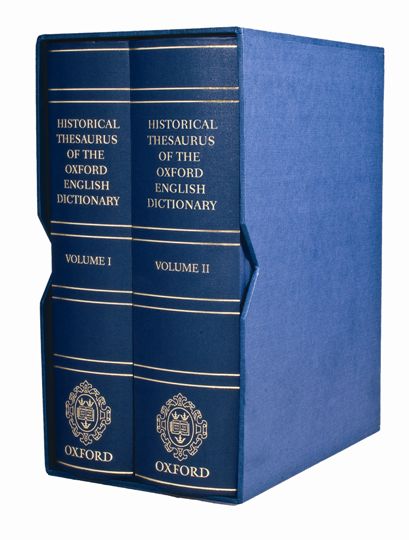

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary… (two handsome volumes) is a great book, a monumental achievement, a truly bright feather in OUP’s cap. It will serve as an inestimable tool in etymological work. When we ask the often unanswerable question about the connection between what seems to be an arbitrary group of sounds (“sign”) and meaning, sometimes our only guide or supporting evidence is analogy. I will use a typical example from my work. The origin of basket (from C

By: Kirsty,

on 11/10/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Reference,

UK,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Tolkien,

oxford english dictionary,

Prose,

hobbit,

JRR Tolkien,

blotmath,

winterfilth,

Add a tag

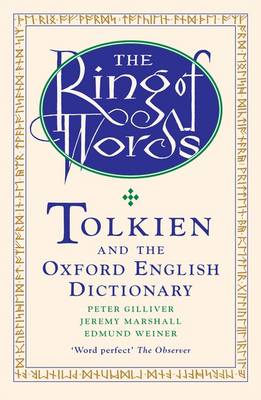

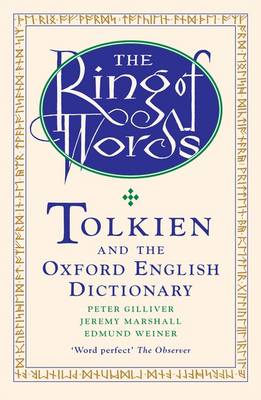

J.R.R. Tolkien’s first job was as an assistant on the staff of the OED, and he later said that he had ‘learned more in those two years than in any other equal period of [his] life.’ In The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary, three senior OED editors – Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall, and Edmund Weiner – explore more than 100 words found in Tolkien’s fiction, such as ‘hobbit’, ‘attercop’, and ‘precious’. Edmund Weiner has written this original post for OUPblog on Winterfilth (October) and Blotmath (November).

As I write this blog Winterfilth is coming to an end and Blotmath is about to begin. What on earth am I talking about? Well, as the Tolkien enthusiasts out there will know, these are the names that the hobbits used for October and November.

As it happens, although the action of The Lord of the Rings spans October and November (avid readers will remember that a lot of action happens in the one and the other is spent by the hobbits resting in Rivendell), these month names are not used in the story. They are given in an appendix in which Tolkien explains the calendar of the Shire (the land of the hobbits) and the hobbits’ names for the days of the week and the months.

As it happens, although the action of The Lord of the Rings spans October and November (avid readers will remember that a lot of action happens in the one and the other is spent by the hobbits resting in Rivendell), these month names are not used in the story. They are given in an appendix in which Tolkien explains the calendar of the Shire (the land of the hobbits) and the hobbits’ names for the days of the week and the months.

Did Tolkien make these names up? No. Some people will be surprised to learn that he made up none of his ‘English’ words, as opposed to the words of the elvish, dwarvish, and orkish languages. (The one exception, funnily enough, may be the word ‘hobbit’—but the jury on that is still out.) The other strange and archaic-looking words, such as mathom, Arkenstone, eleventy, flet, and barrow-wight, are all based on earlier usage and generally go back either to Anglo-Saxon (Old English, English before the Norman Conquest) or to Old Norse (the language of the Vikings and Sagas).

So what about the months? Tolkien borrowed them for the hobbits from Anglo-Saxon texts that give both the Latin names of the months (the names we use now) and their Old English equivalents. None of the latter seem to have survived the Conquest except (in a different meaning) Yule, and Lide, a now obsolete dialect word for March, which may have meant ‘loud’ (referring to its windiness). Blotmath, or rather Blotmonath or Blodmonath, was the time when in pagan times cattle were sacrificed (blotan ‘sacrifice’ or blod ‘blood’).

And Winterfilth? In Old English this was Winterfylleth, in which fylleth means ‘fulness’, or perhaps ‘full moon’. The word for ‘filth’ was spelt and pronounced differently, but in modern English they would have come to sound the same, and this gave Tolkien an opportunity for one of the scholarly etymological puns to which he was very partial.

By: LaurenA,

on 10/30/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

Historical,

Oxford,

Press,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Oxford University Press,

English,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Dictionary,

University,

Thesaurus,

Historical Thesaurus,

HTOED,

Judy Pearsall,

Judy,

Pearsall,

Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

It’s sad, but true. Historical Thesaurus week has come to an end. We feel like we’ve read it cover to cover (to cover to cover) and it’s hard to let go. And so, I’d like to leave you with a valuable lesson I learned: how to use the HTOED to call someone “stupid” in Old English. In this video post, Judy Pearsall (OUP’s Reference Publishing Manager) discusses how words are connected to one another in a HTOED entry, using the example of “foolish person.” Watch the video after the jump.

Click here to view the embedded video.

By: LaurenA,

on 10/29/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading,

Reference,

the,

Historical,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

of,

English,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Dictionary,

Ammon,

Shea,

Thesaurus,

ammon shea,

Reading The OED,

Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary,

HTOED,

Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

Ammon Shea is a vocabularian, lexicographer, and the author of Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages. In the videos below, he discusses the evolution of terms like “Love Affair” and names of diseases, as traced in the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, demonstrating how language changes and reflects cultural histories. Shea also dives into the HTOED to talk about the longest entry, interesting word connections, and comes up with a few surprises. (Do you know what a “strumpetocracy” is?) Watch both videos after the jump. Be sure to check back all week to learn more about the HTOED.

Love, Pregnancy, and Venereal Disease in the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

Inside the Historical Thesaurus

Click here to view the embedded video.

By: Kirsty,

on 10/29/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Christian Kay,

HTOED,

Reference,

UK,

A-Featured,

Dictionaries,

A-Editor's Picks,

Oxford University Press,

oxford english dictionary,

university of glasgow,

Add a tag

Professor Christian Kay joined the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary project in 1969, working on it right up to publication this month. In this original post, she reflects on the successes and challenges of forty years’ work on this amazing feat of scholarship.

Click here to read more OUPblog posts on the HTOED.

Publication of the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary (HTOED) took place on 22nd October 2009. It was celebrated by a party at Glasgow University, where the project was developed, attended by over 100 people. I was proud to be one of them.

The project was started in 1965 by Professor M. L. Samuels, who, at the age of 89, was present at the party and gave a short talk. Also on the platform was another founder member, Professor Jane Roberts, who supplemented our Oxford English Dictionary-based data with material from Old English (c700 to 1150 AD) not included in the OED. The quartet of editors was completed by Irené Wotherspoon and myself, both of whom joined the project in 1969, as Research Assistants funded by the Leverhulme Trust. By that time, Irené was completing the first postgraduate thesis based on Historical Thesaurus materials, A Notional Classification of Two Parts of English Lexis.

The appointment of Irené and myself was a significant departure for the project in that it was an acknowledgment that it would never be completed without full-time assistance – originally it had been conceived as a research activity for teaching staff and graduate students. We settled down with our volumes of the OED and our packets of paper slips to compile data for inclusion in the thesaurus. My first letter was L, which contains some very challenging words, such as ‘lay’ and ‘lie’, whose meanings I had to distribute around the semantic categories of the work.

The appointment of Irené and myself was a significant departure for the project in that it was an acknowledgment that it would never be completed without full-time assistance – originally it had been conceived as a research activity for teaching staff and graduate students. We settled down with our volumes of the OED and our packets of paper slips to compile data for inclusion in the thesaurus. My first letter was L, which contains some very challenging words, such as ‘lay’ and ‘lie’, whose meanings I had to distribute around the semantic categories of the work.

The 1970’s brought other challenges. Michael Samuels and I started working on a system of classification suited to large amounts of historical data, and we began recruiting doctoral students to work on specific sections of data, such as Religion or Goodness. We also faced a situation which was to become horribly familiar: running out of money. My job became part-time, and I supplemented my income by freelance work for publishers and writing textbooks. The situation was saved for me in 1979, when I became a full-time lecturer in the English Language Department. Irené had already departed for the south of England, where she raised three children and continued to work freelance for HTOED.

The downside of having a more secure job (‘at last’, said my family) was having less time for project work. In addition to my new role as a teacher, I found myself increasingly involved with thesaurus administration. We took our first tentative steps into computing at the urging of OUP, who wanted the project delivered electronically, and I spent much time in mutually uncomprehending discussions with computing experts. I also developed skills in fund-raising and people management: in the 1980’s we began to take on trainee lexicographers and typists to do preliminary classification and data entry. When Professor Samuels retired in 1989, I took over the administration completely.

The ever-present question, asked repeatedly by funders, University authorities, and OUP, was “When will the project  be finished?” This was a difficult question to answer, and involved such arcane skills as calculating the number of slips to a filing drawer, multiplying by the number of drawers, and working out the percentage completed in relation to the total in the OED. We came close to finishing in the early 1980’s, when we completed slip-making for the first edition of the OED, but by that time OUP had started producing supplements, and then a second edition, so we ploughed on, combining slip-making with classification. For the remaining years of the project, funding became easier, and we were able to employ both full-time assistants and graduate students on a part-time basis. Overall, I calculate that about 230 people played an active part in the project during its 44-year history.

be finished?” This was a difficult question to answer, and involved such arcane skills as calculating the number of slips to a filing drawer, multiplying by the number of drawers, and working out the percentage completed in relation to the total in the OED. We came close to finishing in the early 1980’s, when we completed slip-making for the first edition of the OED, but by that time OUP had started producing supplements, and then a second edition, so we ploughed on, combining slip-making with classification. For the remaining years of the project, funding became easier, and we were able to employ both full-time assistants and graduate students on a part-time basis. Overall, I calculate that about 230 people played an active part in the project during its 44-year history.

Over the past few weeks, various people (mainly journalists) have asked me “Why did it take so long?” The answer is partly that we never had enough money, but also that work of this kind requires a good deal of careful human input. If you are faced with, say, 10,000 slips containing words which have something to do with Food or Music, arriving at an acceptable classification is not the work of a few hours.

Classification and data entry proceeded through the 1990’s and early 2000’s, with glimmers of light occasionally visible at the end of the tunnel. One highlight of this period was the publication in 1995 of A Thesaurus of Old English by Jane Roberts and myself, which proved that we could at least finish something. Another was my promotion to a professorship in 1996. However, the best moment of all came on 29th September 2008, when the disk containing the final text went off to OUP, followed in August 2009, after a tough period of proofreading, by the appearance in Glasgow of the first copy of HTOED.

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

Today sees the long-awaited publication of The Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary. Conceived and compiled by the English Language Department of the University of Glasgow, and based on the Oxford English Dictionary, it is the result of 44 years of scholarly labour. The HTOED is a groundbreaking analysis of the historical inventory of English, allowing users to find words connected in meaning throughout the history of the language in a way that has never before been possible.

Kicking off some wonderful posts on the HTOED, here are some fun facts and figures about this incredible work. Be sure to check back all week to learn more!

* At just under 4,000 pages, the HTOED is the largest thesaurus in the world. It covers approximately 800,000 word meanings from Old English to the present day.

* The HTOED provides a breadth of knowledge that is found in no other work, and has more synonyms than any other thesaurus. The word immediately, for example, has 265 synonyms, ranging from ædre, which is only found in Old English, to yesterday, which is first recorded as being used in the sense of immediately in 1974.

* It uses an entirely new thematic system of classification, with a detailed meaning structure that distinguishes between true synonyms and closely related words.

* There are approximately 800,000 meanings within the HTOED

* The largest category in the HTOED is “immediately” with 265 meanings

* The HTOED took 44 years to complete (started in 1965, published in 2009)

* In total, 230 people have worked on the project

* It’s taken approximately 320,000 hours to complete the HTOED – that’s the equivalent of 176 years

* The project has cost approximately £1.1million ($1.8million) – roughly 75p ($1.25) per meaning

* The project faced its most significant challenge in 1978 when the building the project was housed in caught fire. The entire archive of paper slips that were used to record each entry were very nearly destroyed. They were only saved because they were in boxes inside metal filing cabinets.

* During the 1980s the Old English material was entered into electronic databases developed in London. The UK government sponsored a programme to train people in editing and data entry skills. The trainees helped to edit and input the bulk of the HTOED data into an electronic system.

* With financial straits being an ever-present backdrop, one team-member, perhaps with excessive zeal, worked out how many pages of the OED could be recorded by a slip-maker within the lifetime of a single pencil (answer: 130)

By: Charles Hodgson,

on 10/15/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oxford english dictionary,

dictionary,

etymology,

Podictionary,

Charles Hodgson,

Philip Durkin,

podcast,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Add a tag

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

This is a special podictionary episode in which I interview Philip Durkin, the Principal Etymologist for The Oxford English Dictionary.

I contacted Dr. Durkin because his book The Oxford Guide to Etymology was recently released in North America and he was kind enough to spend a comfortable 20 minutes talking with me.

I contacted Dr. Durkin because his book The Oxford Guide to Etymology was recently released in North America and he was kind enough to spend a comfortable 20 minutes talking with me.

Podictionary often concentrates on the changes in meaning that a word goes through over time so when we talked we discussed the other side of etymology—changes in word form.

Dr. Durkin explained some of the tools of etymology as well as talked specifically about the etymologies of the words friar and penguin.

At the moment there is no transcript available of this interview but I encourage you to listen either by clicking the “download” link above or via the website audio player.

Five days a week Charles Hodgson produces

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers, Thursday episodes here at OUPblog. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

By: LaurenA,

on 10/9/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

slang,

English,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Dictionary,

The F-Word,

Jesse,

swearing,

profanity,

Jesse Sheidlower,

obscenities,

Sheidlower,

F Word,

Reference,

The,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Add a tag

Lauren, Publicity Assistant

Jesse Sheidlower is Editor at Large of the Oxford English Dictionary and author of The F-Word. Recognized as one of the foremost authorities on obscenity in English, he has written about language for a great many publications, including a recent article on Slate. Here, Jesse discusses the criteria for including certain words or obscenities in dictionaries. Watch the video after the jump.

WARNING: This video contains explicit language.

Click here to view the embedded video.

View Next 5 Posts

As it happens, although the action of

As it happens, although the action of  The appointment of Irené and myself was a significant departure for the project in that it was an acknowledgment that it would never be completed without full-time assistance – originally it had been conceived as a research activity for teaching staff and graduate students. We settled down with our volumes of the OED and our packets of paper slips to compile data for inclusion in the thesaurus. My first letter was L, which contains some very challenging words, such as ‘lay’ and ‘lie’, whose meanings I had to distribute around the semantic categories of the work.

The appointment of Irené and myself was a significant departure for the project in that it was an acknowledgment that it would never be completed without full-time assistance – originally it had been conceived as a research activity for teaching staff and graduate students. We settled down with our volumes of the OED and our packets of paper slips to compile data for inclusion in the thesaurus. My first letter was L, which contains some very challenging words, such as ‘lay’ and ‘lie’, whose meanings I had to distribute around the semantic categories of the work. be finished?” This was a difficult question to answer, and involved such arcane skills as calculating the number of slips to a filing drawer, multiplying by the number of drawers, and working out the percentage completed in relation to the total in the OED. We came close to finishing in the early 1980’s, when we completed slip-making for the first edition of the OED, but by that time OUP had started producing supplements, and then a second edition, so we ploughed on, combining slip-making with classification. For the remaining years of the project, funding became easier, and we were able to employ both full-time assistants and graduate students on a part-time basis. Overall, I calculate that about 230 people played an active part in the project during its 44-year history.

be finished?” This was a difficult question to answer, and involved such arcane skills as calculating the number of slips to a filing drawer, multiplying by the number of drawers, and working out the percentage completed in relation to the total in the OED. We came close to finishing in the early 1980’s, when we completed slip-making for the first edition of the OED, but by that time OUP had started producing supplements, and then a second edition, so we ploughed on, combining slip-making with classification. For the remaining years of the project, funding became easier, and we were able to employ both full-time assistants and graduate students on a part-time basis. Overall, I calculate that about 230 people played an active part in the project during its 44-year history.

I contacted Dr. Durkin because his book

I contacted Dr. Durkin because his book